Maison, in French, can mean both house and home. There isn’t a division between the brick-and-mortar objectivity of a building and the psychological notion in the language. I always think of the Maison Azzedine Alaïa as representative of the latter. Of course, it is the fashion house, the definitive one of our age. But Maison Alaïa is—first and foremost—a home, with all the warmth and intimacy and convivial familiarity that implies.

Maison Alaïa is Azzedine Alaïa’s home after all; he lives here, in this vast space: a 750,000-square-foot, 19th-century building with a cantilevered glass roof, a former outpost of the BHV department store around the corner. It is large enough for the designer to show his collections in a vaulted-ceiling auditorium. (Where he also stages art exhibitions.) The sprawling complex, nearly an entire block, with many twists and turns, contains Alaïa’s studio and ateliers, a boutique, and, idiosyncratically, a small hotel.

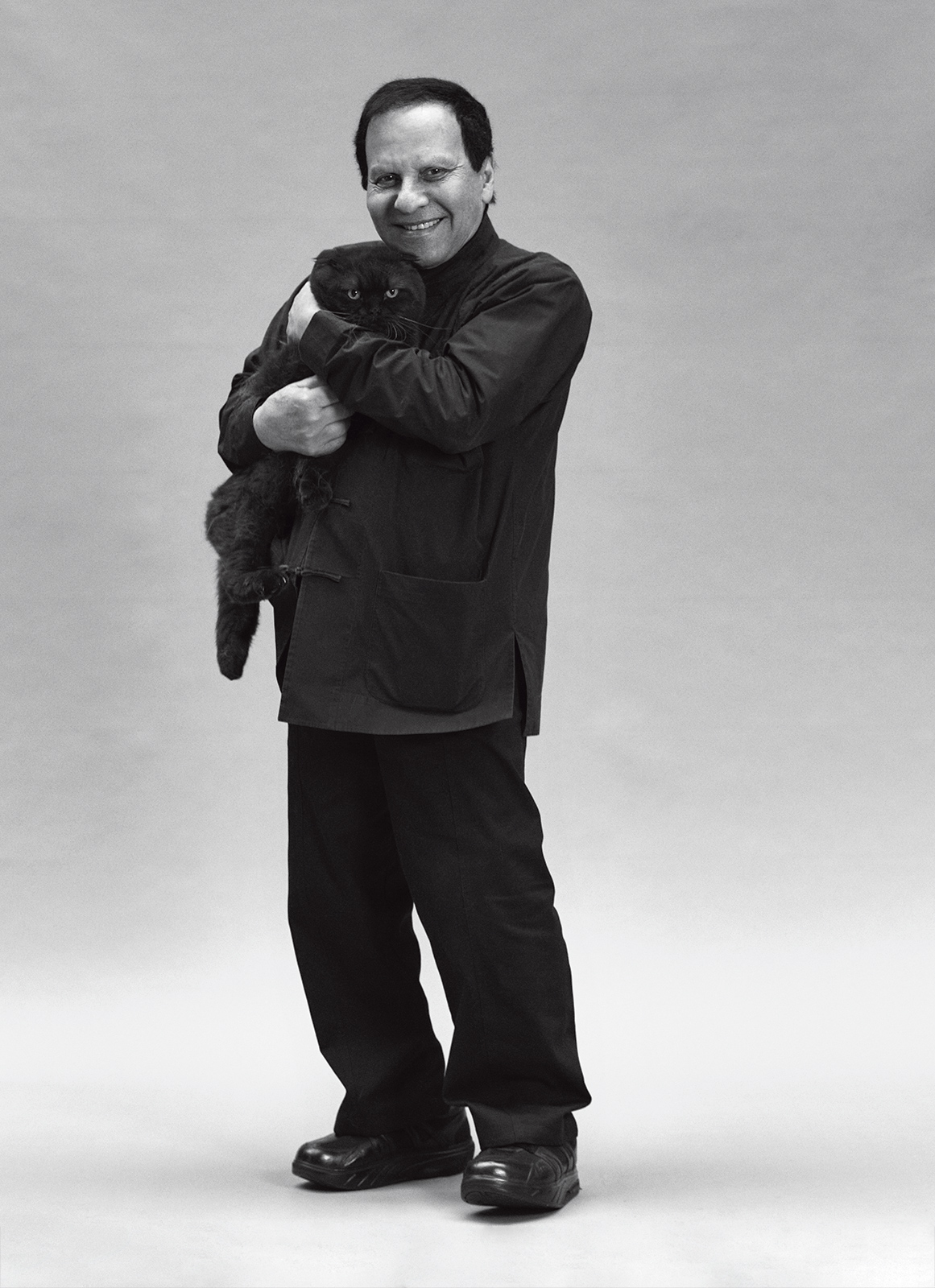

Alaïa is joined by his partner, the painter Christoph von Weyhe, multiple cats, and three dogs—a gargantuan St. Bernard, named Didine, and two Maltese terriers, Waka Waka and Anouar, given to him by Shakira and Naomi Campbell, respectively. There is also an ever-ebbing and flowing number of friends—his right-hand woman, Caroline Fabre Bazin, the curator Donatien Grau, Carla Sozzani of 10 Corso Como, stylists Joe McKenna and Carlyne Cerf de Dudzeele, and perhaps a wild card or two, like the photographer Paolo Roversi, the artist Paul McCarthy, or the author Pierre Guyotat. Alaïa likes lots of people around him. He often invites a friend to his home for lunch or for dinner and ensures they can stay the night in rooms furnished with pieces from his personal furniture collection. It’s an extraordinary setup, deep in the heart of the Marais.

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Plenty of people talk about Alaïa and say he’s unlike any other designer in the world, which is absolutely true. Alaïa’s distance from the other talent in Paris is ideological as well as physical. On Rue de Moussy, the designer is far from the madding crowds, and his clothes reflect that quietness. There’s a certain humble quality to them: materials are honest, like crisp cottons, leathers, and knits; shapes are pure. His clothes are precise, flattering, and generally rather quiet. An Alaïa garment never overpowers. There is an integrity and an honesty to it. Generally, Alaïa eschews decoration that is not integral to the design. He rarely sticks ornament onto anything, at least in the traditional fashion. If Alaïa embellishes, it is keyed to the fabric—knitted in, studded, punctured with holes. Streamlined. There is never anything superficial, or artificial, which is his approach to everything.

Alaïa began sewing in Tunisia, where he was born. We know where, but not when: He doesn’t talk about precise dates, but in piecing together various time lines we can conclude it was likely sometime shortly before the Second World War. Through judicious subterfuge, he was admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Tunis while underage. “When I started, I didn’t tell my parents,” recalls Alaïa. “I went straight there, but I was too young.” He was aided in the cause by Madame Pineau, the midwife who delivered him and with whom Alaïa spent his formative years. It was she who introduced him to fashion at age 10: “Fashion magazines and art books,” says Alaïa, stacking his hands one on top of the other to indicate a jumble of the two. “The first fashion that I remember was [Diego] Velázquez—‘Las Meninas.’” (And, interestingly, in his most recent Autumn/Winter haute couture collection, Alaïa showed a series of panniered ballgowns, echoing the distinctive shape of those in the painting.)

As a student, Alaïa studied art, then sculpture. “Not for long, only three years,” he says, paradoxically. To pay for his art supplies, he worked with his sister for a seamstress in Tunis. One day, while on his way to the seamstress with materials, he was spotted by two women from a wealthy bourgeois family—he piqued their interest, affording an introduction to Madame Richard, a grand couturier in the city who created copies of Parisian styles. He began to work with her, creating dresses for his friends, including the mother of Leïla Menchari, one of Alaïa’s close friends, who now creates the window displays for Hermès. A descendant of wealthy landowners from Hammamet, Madame Menchari offered Alaïa entry into the world of French society. “She told me, ‘I will talk to a friend in Paris,’” says Alaïa. “And then I arrived at Dior.”

He smiles. “So now you have an idea of the start. And you have to now embroider it.”

I hardly need to. Alaïa can spin a yarn. It’s a great story—although dates and ages are still a bit hazy. It doesn’t matter. In any event, Alaïa was old enough in 1957 to travel to Paris and work for Christian Dior. The Algerian War broke out in 1954. Three years later, 1957 marked the controversial Battle of Algiers. Alaïa stayed only five days. He then worked for the couture house of Guy Laroche for two years, “And then I began to work alone,” he revealed.

“There were so many parties. They changed three times a day. It was another life. Today, it’s over.”—Azzedine Alaïa

He already had clients—Simone Zehrfuss, the wife of the acclaimed architect [Bernard Zehrfuss], and the novelist Louise de Vilmorin. He was living with Comtesse de Blégiers, working to create clothes for her and others, later expanding and moving to the Rue de Bellechasse on the Left Bank. It was a tiny, two-room apartment where Alaïa set the precedent of living and working in the same space. He has outgrown the space now, enormously, but his working methods are the same—he still cuts every pattern and sews every sample himself, working alongside his team (there are around a hundred chez Alaïa) but completing an enormous percentage of the work himself. Alaïa is about intimacy. About the personal. The human.

The move to the Rue de Bellechasse—where Alaïa would stay until the late 1980s—came in 1968. “Balenciaga had closed, and I took 18 of his seamstresses. Greta Garbo came and René Clair brought Claudette Colbert.” He shrugs. “I didn’t think about being a designer, a couturier. I was happy to meet these interesting people, elegant women. All the women went to Saint Laurent, Cardin, and me.” Alaïa’s knowledge of women—unparalleled, uncanny—comes from his foundations in the reality of midcentury haute couture. “It was a cycle in their lives,” he states. “They would say, ‘I need an evening dress, and a coat for the day.’ Usually two outfits for day, a dress for cocktails, and an evening dress. One chez moi, one chez Dior, one chez Saint Laurent. There were so many parties. They changed three times a day. It was another life. Today, it’s over.”

Alaïa did not present collections. He created his clothes in collaboration with these women, among the 20th century’s most elegant, educated, and refined. They would explain what they had purchased from other haute couture houses—before 1968, generally from Balenciaga—what they needed from Alaïa, and how it should be. Alaïa would then produce a sketch, and they would order. “They said, ‘What is important is the décolletage, because I have this piece of jewelry. The rest, I don’t care!’” He laughs. “It’s true! At a dinner, all you see is this,” Alaïa says, slicing himself at the waist. “The neckline, the sleeves. The rest is unimportant.”

Given the focus on the décolletage, I ask if perhaps this is where Alaïa began to experiment with his obsession in defining the curve of the cul—what lies beneath the belt. He smiles, wide. “That came later.”

In the Rue de Bellechasse, Azzedine Alaïa operated as a maison de couture, a small and exclusive house for a clientele of the world’s most discerning customers. He was at their beck and call. That isn’t to denigrate Alaïa’s influence on these clothes; they were a conversation between the couturier and his client. From that unique education, Alaïa understood the demands of their lives and the feelings they had about their bodies. Of course, over the period, the Alaïa look emerged—a reaction to what women wanted, keyed to his deep knowledge, flawless technique, and passion for women. He also proposed some radical notions—his tightly cut clothes were provocative, extreme even—yet women seized upon them. They simply looked like nothing else.

But these were private clothes, for private clients. Until the 80s, Alaïa did not stage fashion shows, and his clothes were not shot editorially. It was at the end of the 70s that Alaïa’s aesthetic emerged, fully formed, and began to be captured by fashion magazines. He was commissioned by the shoe designer Charles Jourdan to design a capsule ready-to-wear collection in 1979; he created a selection of leather garments studded, zipped, and pierced with metal; echoing the hard-edged styles emerging across fashion (tellingly, Alaïa worked for a few seasons with his friend Thierry Mugler, whose clothes also leaned in that direction) but underpinned by a knowledge of the female body without parallel in his contemporaries. Jourdan was spooked by the clothes and pulled out, but Alaïa persisted and presented them as his own. They were a precursor to an entire decade, a preview of how women would want to look for the 80s.

“I didn’t think about being a designer, a couturier. I was happy to meet these interesting people, elegant women.”

—Azzedine Alaïa

This wasn’t the only instance. Alaïa’s close-knit, bandage-wrapped dresses of the late 80s prefaced the 90s; his later work, easing us into knits spun magically to stretch and cling and mold, seem psychologically keyed to the past decade, to the changing perceptions of bodies, where comfort is key. Alaïa began working with those around 1990, and the rest of the industry has only just caught up. Alaïa’s intuition isn’t fate, it’s ferocious intelligence. He listens to what women want, from their lives and from their clothes, as keenly as he did in the 60s in the Rue de Bellechasse, when women wanted the necklines carved out for jewels, or when Greta Garbo told him she wanted a cashmere coat with a huge collar to hide her neck (he still has the pattern). And what women want is what determines the fashion of any given period. If it isn’t worn, it isn’t fashion.

At the end of August, when we are meeting, the Alaïa atelier is still on vacation. The home of Alaïa is unusually quiet, bar the occasional sound of his dogs barking. Azzedine Alaïa is making lunch—spaghetti alle vongole, heaping mussels into al dente pasta, with sharp spices. It’s pure and simple food, with superb ingredients sourced by Alaïa himself (lunch is slightly late because he was hunting for fresh spaghetti, in Paris, on a Sunday afternoon).

The trouble with the world’s attitude to Alaïa is that he is not a designer to be venerated. There is nothing precious about what Alaïa does. When he constructs a python coat, he does so not with pins but with strips of adhesive tape, pasting the slithers of snake into position. He compares this to sculpture—and indeed his technique is not that of a couturier, or even a dressmaker, it is something else. Like nothing else. Self-invented, unsurpassed.

But there is also a strong thread of tradition running through Alaïa’s work: a respect for, and deep love of, the customs past and a need to keep them alive. The greatest of these traditions is haute couture, reduced to a loss-leading figurehead, a marketing ploy. A con. Haute couture lives and breathes with Alaïa. Walk into his shop, to its cabine in back, stacked with a smashed plate portrait of Alaïa by his friend, Julian Schnabel (who also created the twisted sculptural bronze clothing racks at the New York Alaïa boutique), and you may see a living, breathing haute couture client being fitted. They’re often fitted by Alaïa himself. His studio is above the store, and he often passes through in a way you hear a lot about from various designers but never actually see. I have seen him there, dozens of times. I’ve also seen the atelier chemises of the Alaïa petites mains and premières hanging on a rail in back, fresh from dry-cleaning.

Alaïa’s knowledge is his greatest asset. Much is made of his superlative craft, his knowledge of dressmaking. Which is understandable: There is no other fashion designer who can make clothes like him. And yet, there’s a deeper level to his clothing. No one else can make clothes like Alaïa because know one understands, the way he seems to instinctively intuit, the way women want not only to look, but to feel. Feeling is what Alaïa is all about. His clothes are tactile, inside and out; they sculpt and mold and twist the body. And they make a woman feel better than any other clothes on Earth.