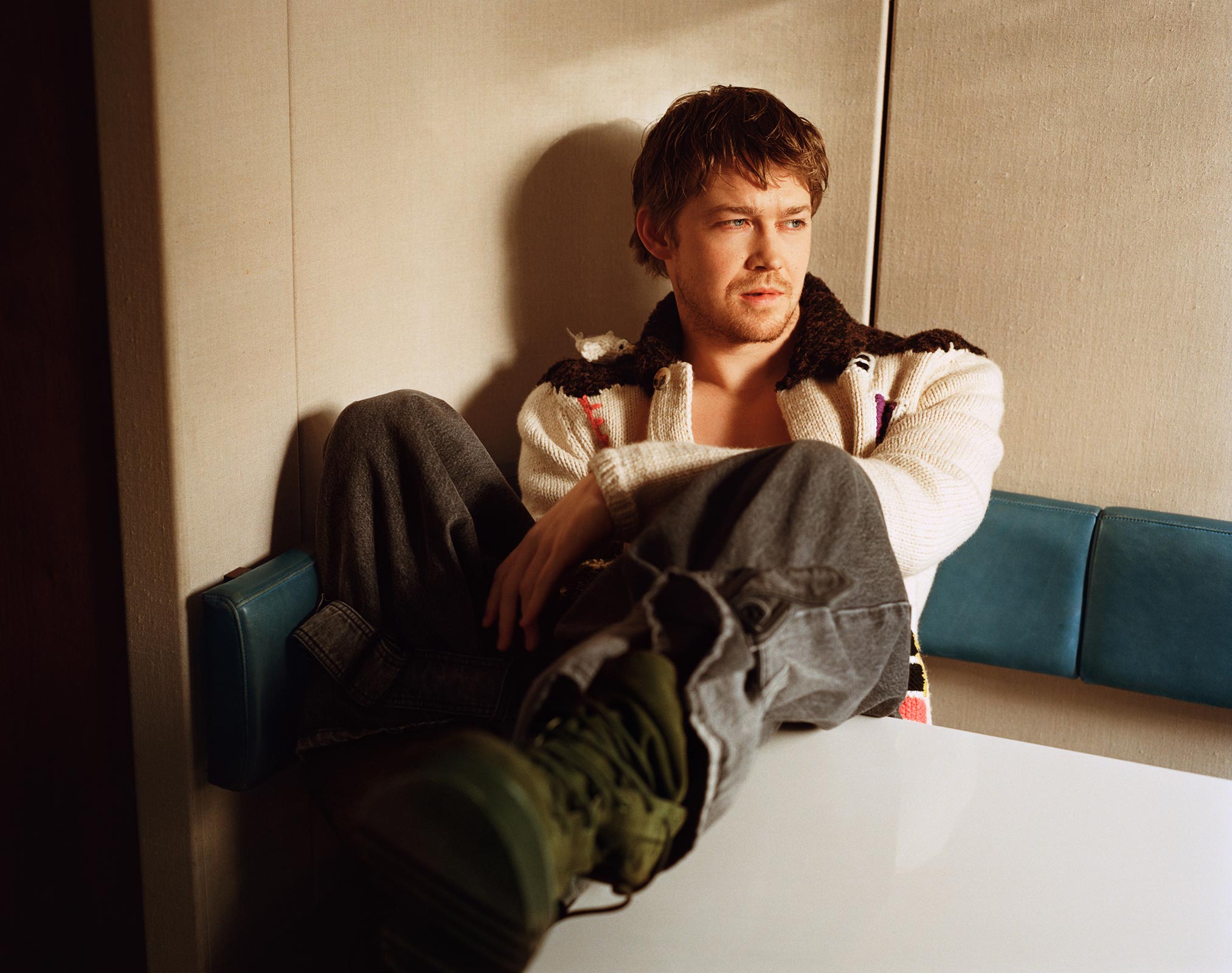

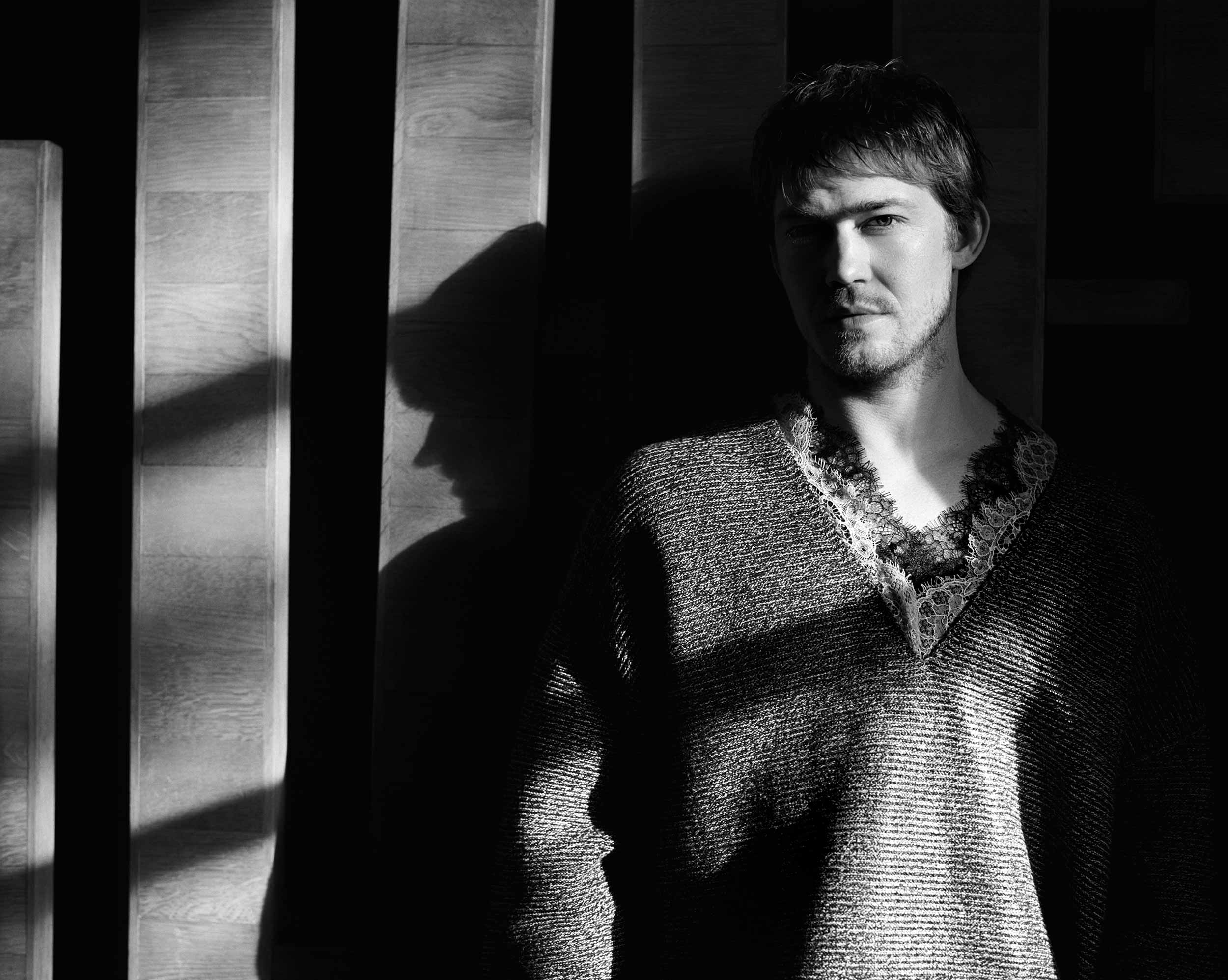

For Document’s Spring/Summer 2025 issue, the actor and designer trace the transformative power of dress and drama

Since debuting on-screen nine years ago as the lead in Ang Lee’s film about a celebrity soldier, Billy Lynn’s Long Walk, Trophée Chopard–winner Joe Alwyn has cemented himself as a versatile performer, adept at bringing complexity and dynamism to morally conflicted—or even ethically bereft—characters. The London-raised actor has played an 18th-century baron (The Favourite, 2018), a malignant college student (Boy Erased, 2018), a 16th-century lord (Mary Queen of Scots, 2018), and a slave owner (Harriet, 2019), as well as the married love interest, Nick, in the streaming adaptation of Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends (2022). In last year’s The Brutalist, the Oscar-nominated drama starring Adrien Brody as the Hungarian-Jewish architect László Tóth, Alwyn conjured the cruel image of inherited entitlement as the industrial heir Harry Lee Van Buren.

The 34-year-old Alwyn barely posts on social media. He’s not spotlight-shy, but he has the mildly reserved charm one associates with stars of the ’60s or ’70s. His focus is on the craft of acting, which he studied at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. A true student of theater history, his upcoming films include the Aneil Karia-directed adaptation of Hamlet, in which he plays Laertes, as well as Hamnet, a historical drama directed by Chloé Zhao, which follows William and Agnes Shakespeare in the aftermath of their son’s death.

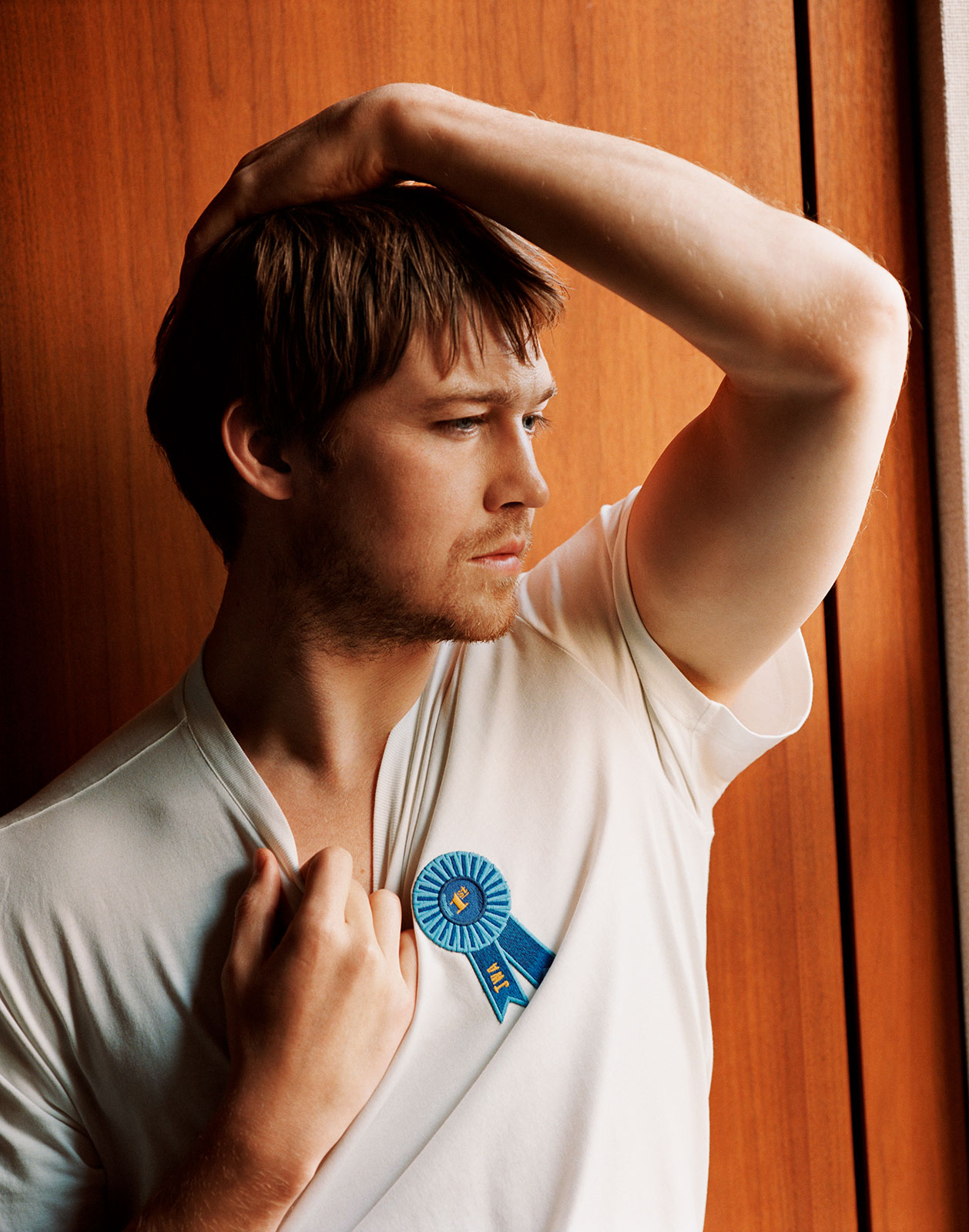

Fashion designer Jonathan Anderson likewise brings range and rigor to his work in fashion and art. Recently named to the helm of Dior Men, the Northern Ireland–born designer shot to attention after launching his eponymous JW Anderson label in 2008 at just 24. With the brand, he produces whimsical yet studied reflections of fashion’s history and fashion’s present that playfully challenge convention. Anderson’s early collections blended chunky traditional British Isle knits with sheer, stitched, and sexy layers. In the late 2010s, he designed semi-uncanny garments whose elongations and angular hems subtly reshaped the wearer’s anatomy, and his most recent men’s collection included quilted coats reminiscent of duvets and sweaters adorned with Guinness logos and graphics. From 2013 until March of this year, Anderson also led the Spanish label Loewe, turning it into a critical and commercial juggernaut and founding the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize, which celebrates craftspeople and designers pushing the boundaries of their respective forms. At Loewe, he’s also worked with artists like Anthea Hamilton on performance costumes, and with artist foundations on fundraisers, like the 2018 benefit for Visual AIDS that featured t-shirts with prints pulled from David Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre.

Anderson—who briefly trained as an actor in his youth—has made his own foray into cinema as the costume designer for Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers (2024) and Queer (2024). In both films, the garments help convey not only the affect and world of the characters, but also their evolutions—whether it’s the development of Zendaya’s Tashi from tennis star hopeful to steely ultra-coach or the effects of infatuation and the impossibility of returns on William, played by Daniel Craig.

For Document, these mutual fans met up in London to chat about creating multidimensional worlds in cinema.

Drew Zeiba: How did you get connected?

Jonathan W. Anderson: I was doing the third edit of Queer, and then Luca [Guadagnino] was, like, “We’re going to meet Joe.” So I was like, “I’ll tag along.” And we had pints at Blue Posts in Soho.

Joe Alwyn: Delicious pints.

Jonathan: Very British and very London.

Joe: We almost could have, in another universe, crossed over a few years before, with Luca, when he was planning to make Brideshead Revisited. I forget when that was—2020?

Jonathan: I think so. That was the first time Luca had gotten in contact with me to do costuming. And then it didn’t happen. But that’s how then Challengers happened.

Drew: You brought up Brideshead Revisited and Joe, you’ve done so many period pieces. I’m wondering about reference and history. Likewise for you Jonathan, I see a lot of attention to legacy and craft in the work you do as a designer, as well as in your costumes for film. What is the relationship you both have to digging into the past—personal archives, historical memory—as you’re building out characters, whether through clothing or acting?

Joe: When there’s a mixture of both period and contemporary, that seems to take off in a more interesting way. I’m thinking of a film called The Favourite, which was directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. I think lots of people connected with and liked it because it’s a period film, but the tone of it and the shape of it isn’t the usual kind of stuffy, fixed idea of what you’re used to seeing when you see a period film. The film was also bawdy and irreverent and crude and sexy and all these things that people weren’t used to seeing fit into this kind of story.

Jonathan: I was always fascinated by that film. For me, it’s nearly like a [William] Hogarth painting. I love the angles. If you look at the costumes, for example, the wonderful Sandy Powell cut everything out of denim, which I found really interesting.

Joe: There’s a similarity in that mixture of the two things to what you do. Even with your Guinness collection.

“I always wish that you could do fittings sooner and take costumes home for a couple of weeks and wear them around the house.”

Jonathan: When you go back into anything historical, you have to ask, How do you articulate it to an audience today? You intrigue them through the idea that there is a contemporariness, even if it’s historical. No matter if it’s with fashion or film and music, you’re trying to connect them to history in a way that makes them feel like they’re part of it or trying to relate it to certain things in the social iconography of the moment. You can’t rely on nostalgia to make it work, ultimately.

When I did Queer, I had Daniel [Craig] in front of me as Daniel the person. I sat there for over half a day working with him on the clothing of the character, prosthetics, and the eyewear, working on all these different things, and then suddenly there’s this very strange moment when the person is no longer themselves. They are someone else in front of you. There is something quite surrealistic in this moment. When you put the clothing on, you really see this three-dimensional thing in front of you, the character. It’s like a kind of moving feast when you’re working with great people.

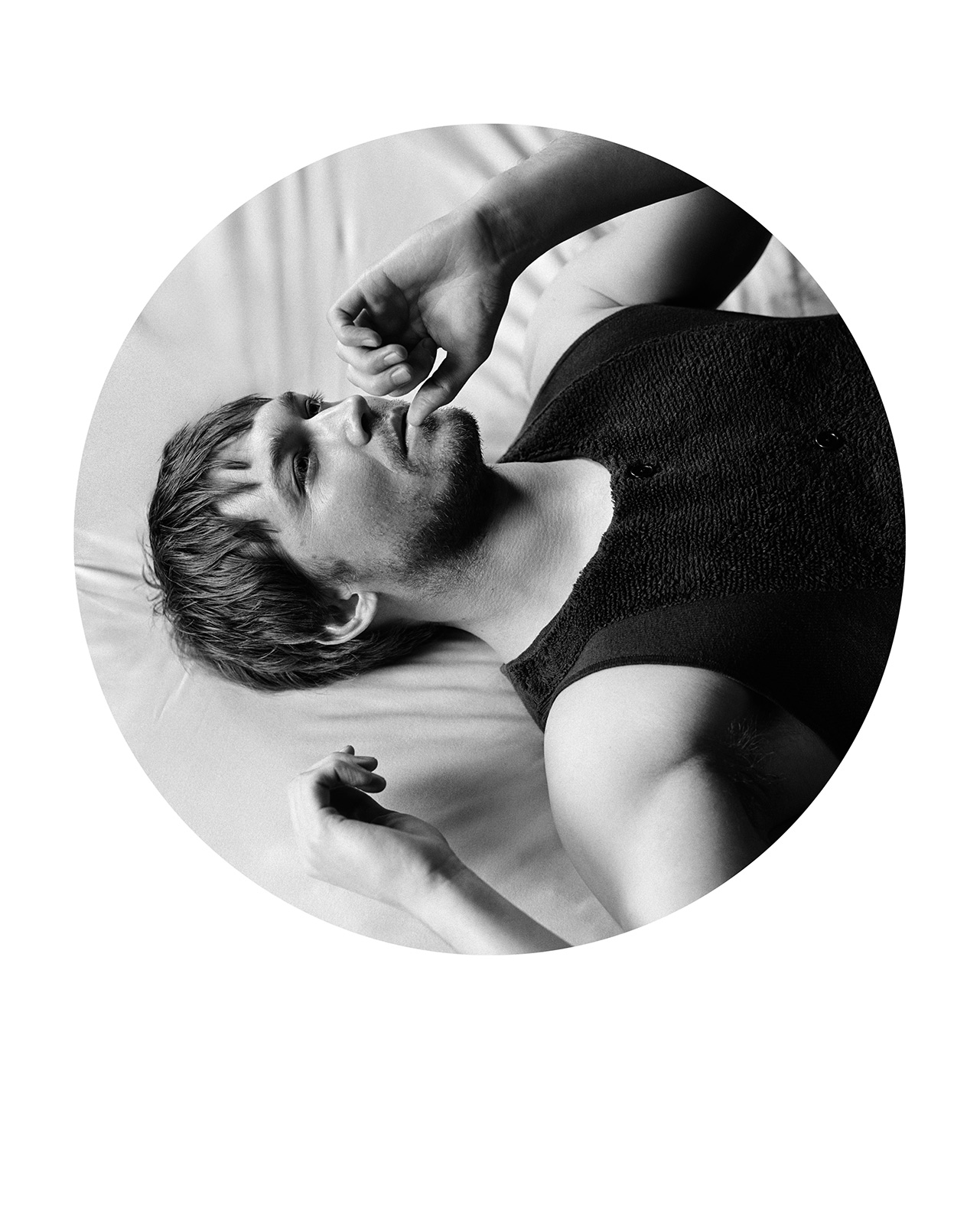

Joe: I always wish that you could do fittings sooner and take costumes home for a couple of weeks and wear them around the house. It really does make such a difference in the way you move, the way you start to think, the way your body feels. It’s so informative. Even thinking again of a film like The Favourite when you have these little heels on which you’re not used to wearing at all, you find yourself carrying yourself in a completely different way. Or the very first film I did, I played a soldier. We went to military boot camp and were buttoned into the same uniform for two weeks straight, and it became a new kind of skin.

Jonathan: Even if you don’t work in film or you don’t work in fashion, we all have in us this idea of dressing up to become something. No matter how professionalized everything gets within my world, there is always this amazing, naïve moment when someone is trying on clothing to become a character in a film where they go on a journey to be something else. I think that is like a childlike quality in all of us, this idea of the dress up.

Joe: I also think certain clothes, especially literal uniforms, are so coded and have different meanings. In The Brutalist, there’s a moment when Adrien [Brody]’s character, László, goes to this big estate for the first time, and they say, “Will you wear this tuxedo?” So that he blends in. It’s something that, on the one hand, should make him feel included, because he fits in and he looks like everyone else…

“But when it comes down to just brass tacks, basic things, if you cannot embrace, in society, the idea of immigration, then you have no idea how civilization was built and how you can learn from one another.”

Jonathan: …but he becomes alien in the situation. Tell me about The Brutalist, which is a fantastic film. How did you tackle that one, compared to other roles you have done before? There’s something about this film that is so harsh, but there’s an amazing stylism that throws you sometimes. If you think of Brutalist architecture, there’s something about this idea where you’re teleported in [a structure] and then teleported out, in terms of style and performance. What was your starting point?

Joe: Well, first and foremost, I thought [the script] was unlike anything else I’d read. It felt like a big, old-fashioned, rigorous American epic, in the vein of, I don’t know, Orson Welles meets There Will Be Blood. It felt very complete and tight on the page. And it’s heavy. I liked the scope of it. It was asking so many big questions—about the immigrant experience and art versus commerce. But it also felt very, very personal and intimate, and I think in the end, very real. I just hadn’t read anything like it, and I was intrigued by the idea of Harry being part of this family. I do find the psychology of those big, often American, capitalist families quite interesting. Obviously, you have even Trump about to step into the White House, and you have Succession on TV. I found it compelling: Where is your place in that as the “son of” who’s probably grown up with far too much of one thing and not enough of the other?

The film is also about America’s relationship to the outsider, with László and his relationship to Europe. It’s brutal in more ways than one.

Jonathan: I think film is very important in the historical context of the trauma—of brutalness, ultimately—within society. It is able to remind us of what we continuously need to learn from the past.

Joe: And everything that’s going on today with immigration in America.

Jonathan: That’s what I mean. Immigration is such a powerful creative tool because ultimately, it’s about discovering the new and embracing newness within each other. Ireland, without being able to embrace one another at one point, would never have been able to find a solution.

What I find really fascinating when I go home at Christmas is that immigration has improved the country because people bring in knowledge, people bring in different eyes on the situation, and diversity and different cultures. Growing up, it was such an insular society because no one wanted to go there. Why would you? Why would you move to Northern Ireland in the ’90s? Now when I go back, it’s so amazing; there’s so much openness, there’s a whole other world happening. I don’t have any political viewpoint that will ever air. But when it comes down to just brass tacks, basic things, if you cannot embrace, in society, the idea of immigration, then you have no idea how civilization was built and how you can learn from one another.

Joe: I find it moving in The Brutalist. It’s through his going to America and by fighting tooth and nail to build this monument that he manages to unpack some of his trauma from what he has come through. You don’t know that until the end. The reason that he’s been so dogmatic about the dimensions of this building is because he wanted it to match the camps that he was in. But it takes him getting away, going somewhere foreign, in order to deal with this trauma from home.

Jonathan: In Queer, for example, I actually love that moment when he does go back to Mexico City thinking that it will be the same. I think we all can relate to that experience: You try to impress the environment you’re in. You try to make yourself look slightly better, hoping that you’re going to cross paths again, even though you know it’s not going to happen. But you do it anyway, thinking that you can reenact what is no longer there.

“when you see a cut for the first time—like it or not—when you see what the editor has done, when you see what the score is, how it’s color graded, it is magic.”

Joe: You knew the book before?

Jonathan: Yeah, I read the book when I was at university at the London College of Fashion. I think I read it because of the title. I knew nothing about [author William S.] Burroughs when I read it, and then I got into that whole thing, like, [Robert] Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith, [David] Bowie, because Burroughs became this weird pilgrim figure that people went to have an adjacency with.

Joe: He was married too, wasn’t he?

Jonathan: Yeah, he was the one who shot her in the head.

Joe: Right. Did he shoot his wife on purpose?

Jonathan: It was by accident. It was in a bar, and I think he was trying to shoot a glass [balanced on her head].

There was something about the music, the tension, Daniel in that scene, and this idea that there is nothing more petrifying than destruction and nothingness. Even if I was to come into that scene randomly halfway through watching the film I’d find it deeply chilling.

Joe: Everything starts to disappear.

Jonathan: Everything starts to disappear. That, for me, is one of the key moments in the film. All the oxygen in the room is taken out. That’s what’s magic about cinema. Because when you watch a film, you get a visceral reaction from it. You are invested in the emotion. There’s nothing more rewarding than watching creativity in that way. Even by working behind the scenes on film, I still have the romance for it.

Joe: It doesn’t demystify it. I mean, when you see a cut for the first time—like it or not—when you see what the editor has done, when you see what the score is, how it’s color graded, it is magic.

Jonathan: Still, to this day, we are obsessed by cinema. It’s the most cliché thing, but the imitation of life is the most fascinating thing to watch. You see that all these genius creative people in a room are adding to the tapestry directed by this one person who’s taking this vision and bringing it all together, and by chopping it and cutting it and painting it, and suddenly it’s like, bam. You have this end product.