At once a perennially emerging designer and a legend amongst fashion insiders, Andre Walker is one of the industry’s most elusive figures. At a time of live feeds, Klout scores and unflinching views beyond the drawn curtains of the beau monde, mystery is an art form—even more so for one of the fashion world’s most discreetly lauded members.

Coming and going over the past three decades, the London-born peripatetic staged his first fashion show in the 1980s, aged 15, in New York’s Oasis club and had his own fashion line by the age of 18. Following a move to Paris in the 1990s, Walker then lent his prescient design hand to Marc Jacobs, Louis Vuitton, and Kim Jones as a consultant. A design philosophy purposefully devoid of commercial intention saw a stop-start in the progress of Walker’s personal ventures before a brief revival in 2014 via an exclusive line for Dover Street Market commissioned by Rei Kawakubo and Adrian Joffe.

Above The Fold

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Embodying Rick Owens

Toasting the New Edition of Document

This season, Walker returned with a presentation on the steps of Paris’ Musée des Arts Decoratifs; a collection based upon works from 1982 to 1986, sourced from the private collections of Patricia Field, Kim Jones, Christiaan Houtenbos, Kim Hastreiter, and Henny Garfunkel, to be made available for wholesale purchase from 2017 to 2020. Full of the curvilinear lines, extruded silhouettes, and engulfing volume for which he has been so well known, the assembly extols the unique wit and humor of Walker’s free-cutting technique and design hand.

Sitting down to talk to Document outside his Paris showroom, the day following the presentation, a steady stream of buyers and editors halt the conversation to heap praise onto the designer. Whether he wants to or not, it’s clear Andre Walker will not be disappearing again any time soon.

Divya Bala—The pieces you revived for this collection came from 1982-1986. Was the legendary runway show you did at 15 during this time?

Andre Walker—Yes, it’s from the East Village Boy Wonder period. [Laughs]. I actually don’t have an archive.

Divya—So, how did you source the original garments?

Andre—A lot of them came from Pat Field. She had about 13, maybe 20 pieces, something like that. And then Kim Hastreiter has five really amazing coats and one skirt. Then Christiaan [Houtenbos] had that one short-back cape—I don’t even remember making that. But the reason I don’t have any of the clothes was that after any of the collections I would show in New York at the time, I would take all of the collection and dump them into Pat Field’s boutique so they could sell them. They were all originals. There was no production but there was a huge stock. The collections I was showing were 40, 50, 60, up to 120 pieces of clothing each.

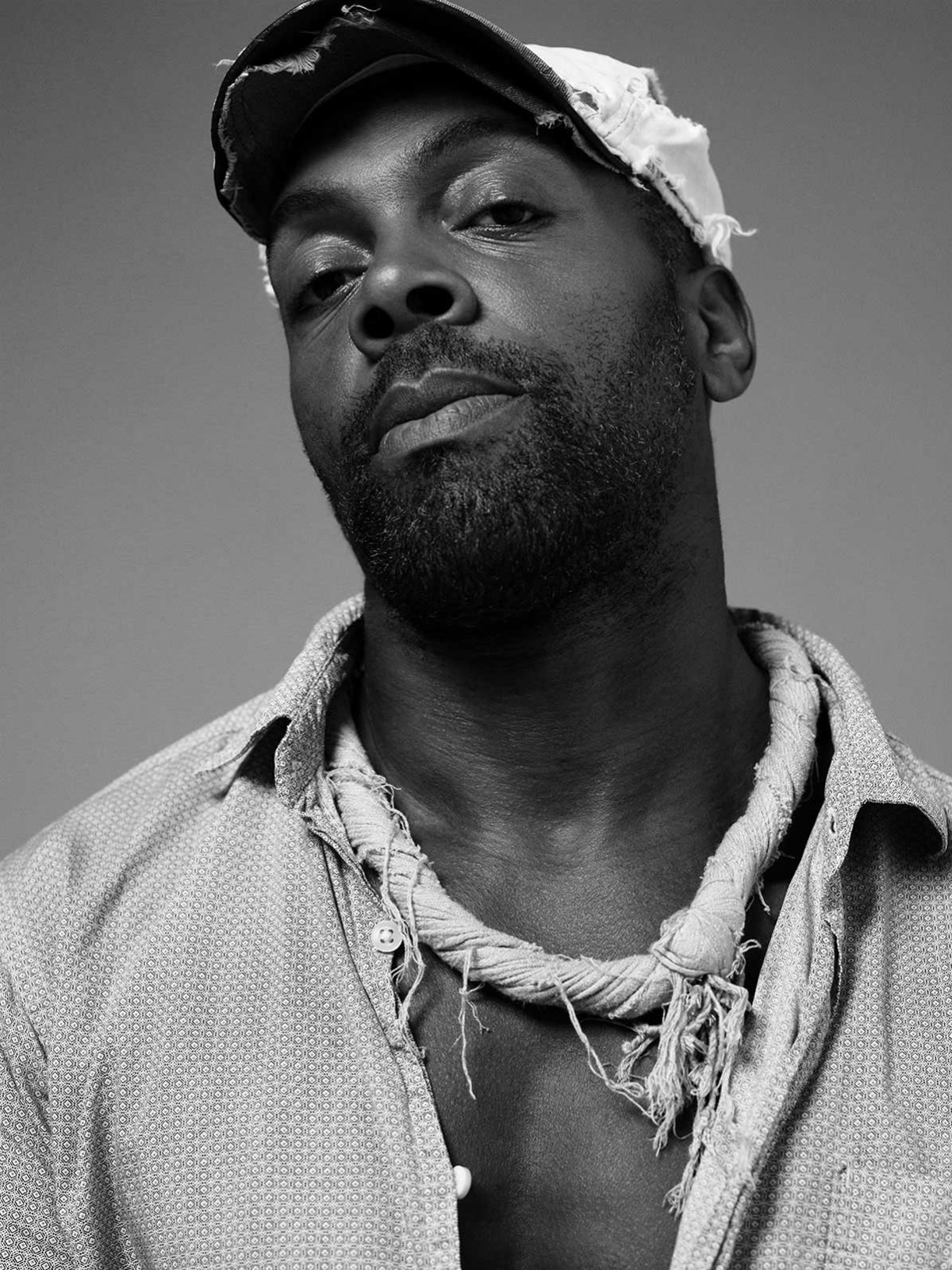

Andre Walker featured in Document Journal No. 3. Photographed by Catherine Servel.

Divya—How did you put those collections together?

Andre—With the help of a fabric store in New York called Diamonds. I can admit today that I was actually pinching money from the till of my mom’s beauty salon! Plus, I was making t-shirts when I was 11 to 13. Hand-painted t-shirts, fringed, cut with scissors, and ripped and slashed and tied back together. Sometimes I would rip the body off a t-shirt and add it to another to make a dress.

Divya—What was it like being a kid designing in New York City back then?

Andre—I have no idea. All I know is that my brain was buzzing. It was full of Vogue Italia, Vogue Paris, W Magazine, City Magazine, and Jill—I was a magazine junkie. Blitz, The Face, Soho News, After Dark, Playgirl. You know what I mean? Everything! For me it was just teaching myself how to make clothes, that’s all I wanted to do. All I wanted to do was compete on the international fashion scene with the designers in the magazines I was reading.

Divya—So why that period and why now?

Andre—Because that was all that was available to me. My mission was not to create or reproduce an archive but that was the intellectual property that was screaming at me at the time. Friends were nudging me and saying, ‘Hey, I have a garbage bag full of your stuff. Come pick it up if you want.’ It just occurred to occur.

Divya—What do you think of the state of the industry now? It’s so different to when you were first designing.

Andre—I feel like I’ve been super unattentive. Like, mal cultivé. Maybe over the past ten years, I’ve realised what I’m dealing with. And maybe in the past five years, I’ve realised how I can participate in a coherent manner. I was forced into that by my affiliation with Comme des Garçons and Adrian Joffe because it was an opportunity I could not refuse. It was so prestigious, good, and cool. It was like a medal of honor, I guess. I think the only reason I could be sitting here with the collection I have now in the showroom is because of them. Before, all I knew how to do was entertain with my designs.

Divya—What do you mean by that?

Andre—It’s more like a laboratory. Like, a culmination of intellectual property, ideas, philosophy, and ideology are the rewards of your efforts, and not so much monetary. So that’s been my life. The prestige of being affiliated with like-minded people who are zooming way ahead has kind of been my distraction and predilection over the years, for sure.

Divya—What do you think about fashion as communication?

Andre—I was just talking about that today. It’s all about communication. The more you hold back or the less you share, the less you get. But I don’t know, it’s not necessarily true. There are some people who like the presence of absence, they live on that. Whereas I live on the opposite in a sense. I like the presence of presence. I like to know what’s happening.

Divya—Do you feel liberated now?

Andre—I guess. All I know is that you just have to do what you have to do. Someone was saying to me, ‘Oh fashion is so difficult [these days],’ and it’s really not at all. I was saying, ‘If I can do something in fashion, anybody can.’ Seriously.

Divya—Why do you feel that way?

Andre—Because I never thought about it as a business. It’s just been a hobby and a joy and a preoccupation for me. A distraction. I didn’t study fashion. That’s why those clothes were cut the way they were and why the collection is called ‘Non-Existant Patterns’. The most technical thing I did with those clothes was lay the fabric on the floor and fold it over, so that it was the same length in the back and the front. Every single one comes from my drawings. It was all imaginary designs from my sketchbooks that I ventured to realize in the freehand cutting of fabric on the floor. So it wasn’t freehand pattern cutting, it was freehand fabric cutting. You cut the fabric and then you head over to the machine. Super interesting. And I’m going to hold on to that principle. It’s how I do it. You know how Azzedine Alaïa has his way of piecing bits around the body together? I have something too.

Fabric swatches. Image courtesy of Andre Walker.

Divya—Your pieces can look quite foreign on the hanger—they are not simply a denim jacket or a t-shirt—you have to engage with it and consider how to wear it. Who do you see wearing it?

Andre—It’s for fanatics and the adventurous. And for people who happen to be surprised when they try it on and discover, ‘Wait a minute, I like this.’ I also love the fact that this collection is one size fits all. I like the fact that it can fit lots of different body types. I think fitted clothes are overrated anyway—with a few exceptions.

Divya—Has the way fashion fits into society today changed?

Andre—Well, what is society today? Society has been infiltrated by media and technology so there’s another player involved now. The emotion has been zapped out of society. In fashion, people have become so gluttonous for aesthetic and reference and culture and relevance, which is really unfortunate. What is relevance? What is culture? What is aesthetic? A lot of those terms are devoid of any need for emotion or emotional value. I’m much more interested in the heart at this point in time.