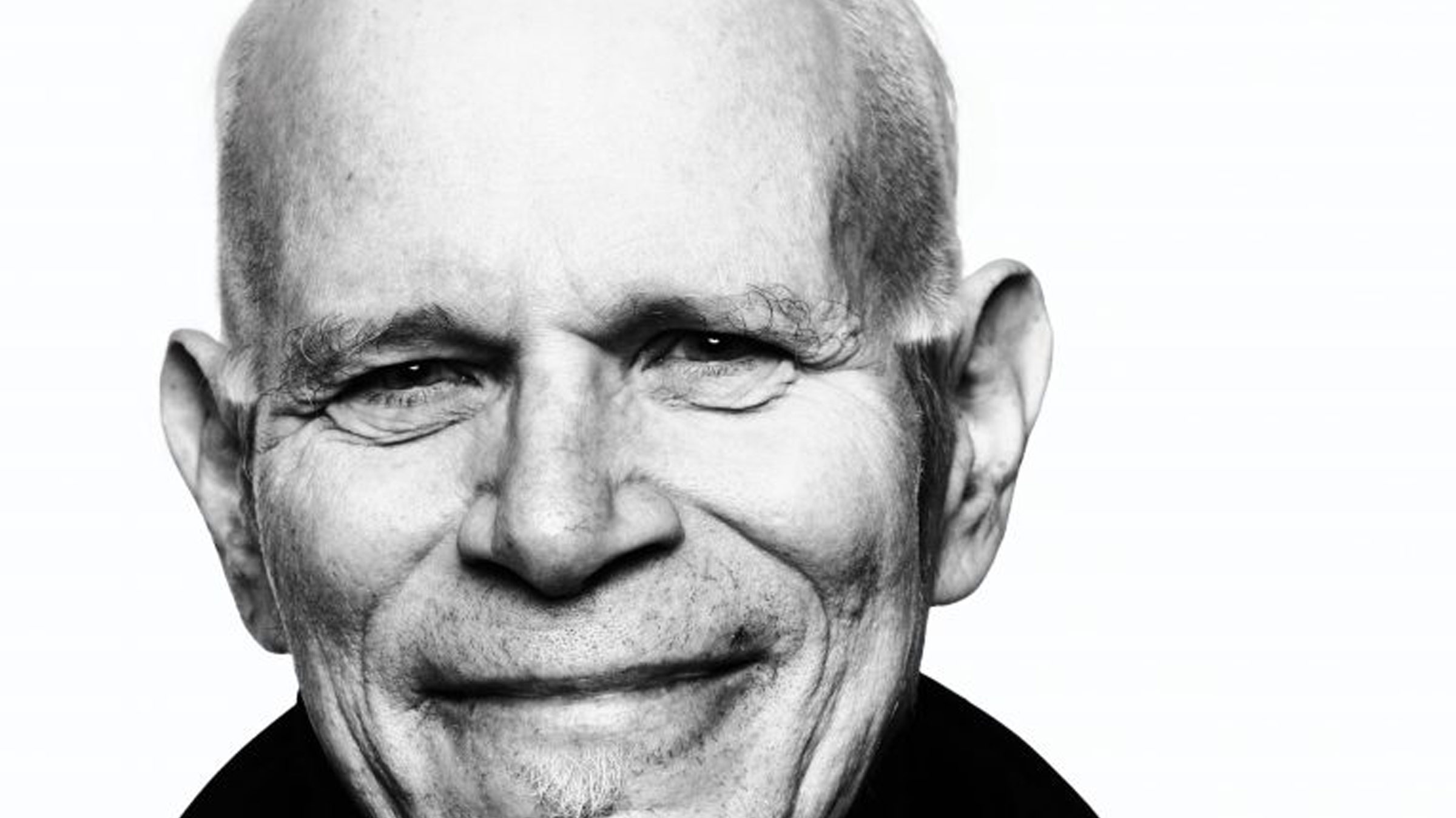

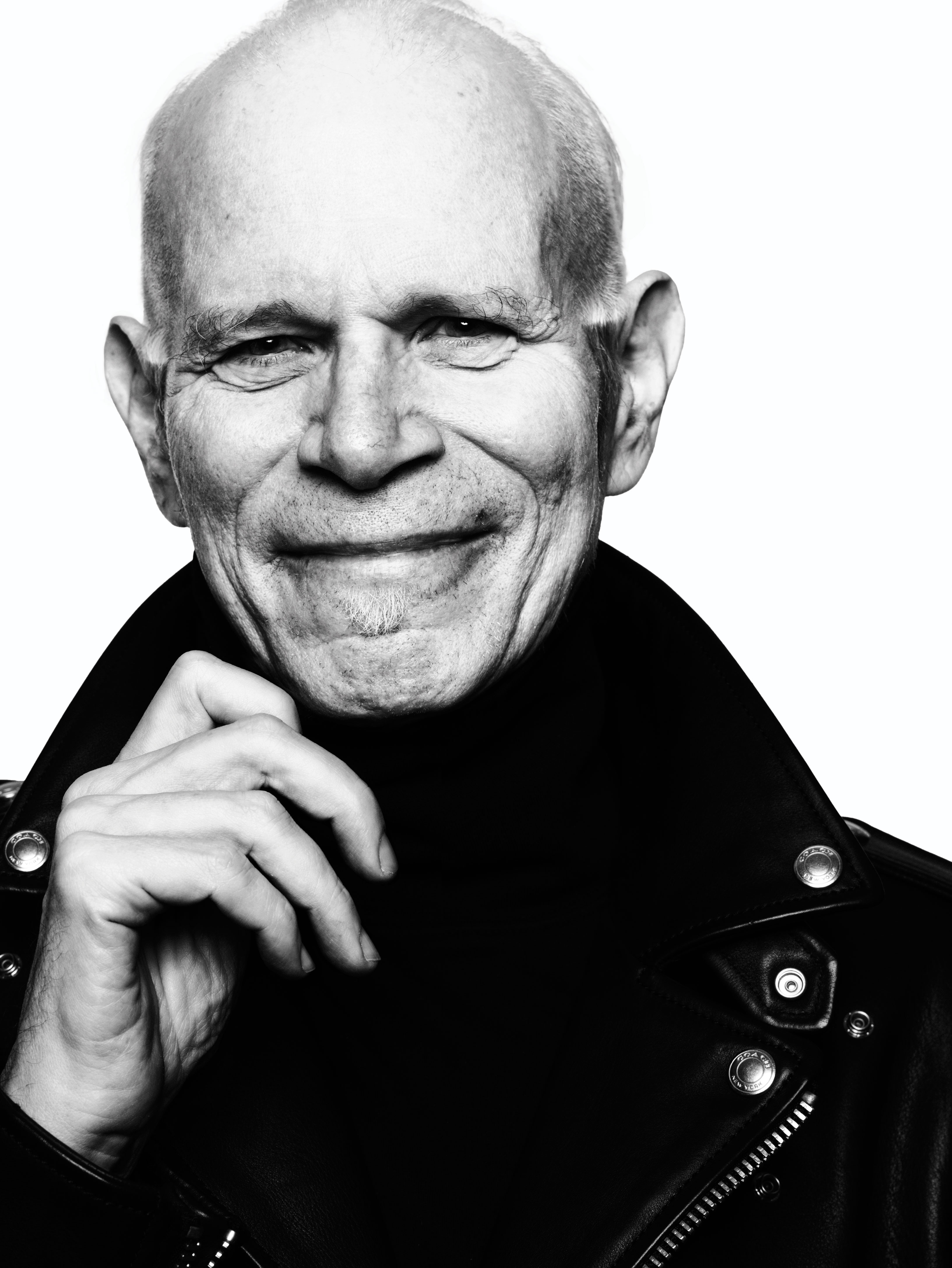

An early adopter of video art, Charles Atlas has recently seen his films go from downtown fringe to larger-than-life as part of New York’s Times Square Arts Midnight Moment series. From developing the genre of video dance while working as Merce Cunningham’s stage manager, to his longtime collaborations with Michael Clark Dance Company, Atlas revisits lost footage from the 80s, directing secret pornos, and seeing Leigh Bowery for the first time out of costume.

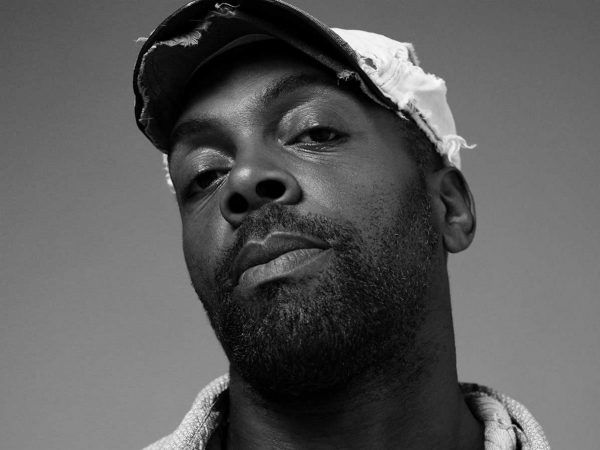

STEWART UOO—So you’re currently working on a show that is going to open in

two weeks at Luhring Augustine in Manhattan?

CHARLES ATLAS—This is the first time I have had a show in Manhattan since 1999, which was the first show I ever had in a gallery. It was portraits at a gallery called XL, which has since moved to Berlin. It included Teach and two other pieces. I don’t know if you’ve seen Teach; it’s an installation with Leigh Bowery lip-syncing. He took safety pins and pinned on fake lips over his lips. I had always wanted to do a lip-sync like that.

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

STEWART—Was it a look that he did before or was it an invention you guys did?

CHARLES—It was a look he had done. I told him, “Next time you come to New York, bring your lips.”

STEWART—Were his cheeks already pierced?

CHARLES—He had pierced his cheeks for another look. He had LEDs on his teeth, and he pierced his cheeks, so he could put battery wires in his cheeks. He wanted the look of battery wires going into his mouth. But it tasted so acidic, so he didn’t have them for long. But then he had holes in his cheeks, so he invented his thing with pinning lips on. It was a little painful.

STEWART—How many videos and films did you make with Leigh?

CHARLES—I think three or four with him; and then for the Michael Clark Company, there’s a few more.

STEWART—I became familiar with your work through YouTube. I googled Leigh Bowery and Michael Clark and came across your work. I remember first seeing the dance sequences from Hail the New Puritan. That film really inspires me so much. I actually watched it the other day when I was getting ready to go out.

CHARLES—I used to hang out at clubs. But you know in those days, the clubs closed really early, around 1am. And so sometimes getting ready, the looks had elaborate make up and took hours to finish. They used to do it every night, so we would only arrive at the tail end of the party [laughs].

STEWART—How did you first encounter Leigh?

CHARLES—I met him at a nightclub. We got to know each other because he worked with Michael. For maybe two years, I had never seen him out of drag. And then one time when he came to New York, he stayed with me. When he came through the door, I was in total shock to see what he really looked like.

STEWART—Did you ever see him during the day? Was he was always kind of dressed up?

CHARLES—No, it was a sick look for the day, a bit like a child molester [laughs].

STEWART—When he first came to New York, did you guys work together a lot?

CHARLES—We partied a lot. I used to go out with my camera, sometimes to club performances. But when I went out with Leigh it was too much fun—I couldn’t take a camera along.

STEWART—You must have all this weird footage.

CHARLES—I have all this footage I haven’t transferred and can’t even look at from 80s, which I would love to see. There’s just too much of it.

STEWART—You have tons of reels?

CHARLES—I don’t know if it still would play. There’s a system now where you bake the videos, play them once, and then transfer them. There’s actually an archival studies class at NYU who took a couple of my videos—we’ll see what they can do. They even have black and white video from the very first theater piece I ever did. I would love to see that, but I doubt it will play.

“I love new technology. Everything I’ve ever done—filmmaking, video, computers—I learned from books. I’ve never had a class or anything like that.”—Charles Atlas

STEWART—What’s the first theater piece you did?

CHARLES—I did a couple theater pieces early in my career. I was invited by Robert Whitman to do a piece during a series of evenings of artist performances. Robert, Red Grooms, Robert Israel, and I all did live performance pieces.

STEWART—You’re in front of the camera? Or did you choreograph and direct the theater?

CHARLES—I wasn’t in front of the camera because I didn’t perform. I created a performance piece for other people to perform.

STEWART—What was it called?

CHARLES—Little Strange. It was based on a painting by Manet called The Old Musician. It’s not considered one of his “good” works, but I love it. It has a bunch of different characters that look like they’re from different paintings: a dancer, a performer, a ten-year-old boy, a girl. In the performance, things went up, things went down. At the end, the actors formed that painting in real life. It was all done to violin music by Django Reinhardt.

STEWART—How long was that performance?

CHARLES—It was about 30 minutes and the first time I did anything like that. After the performance, I watched the film and cringed. All I could see were mistakes. Then someone called and said how much they loved it, that made me go back the next day and do it again. There was a weekend of performances. I can’t remember exactly, but I think it was 1972. I then did a theater piece in 1974 based on Lillian Gish with ten girls dressed up like her. It was called

Wonder, Try (Sketchy Version). They did this dance I created based on Lillan Gish’s gestures from her silent movies. It was about an hour, in two acts. I had learned from the one before that I didn’t want to watch it, so I was in it. Hardly anyone saw it.

STEWART—You worked behind the scenes in theater. Did you study stage managing?

CHARLES—I was a college drop-out and came to New York. I volunteered as a stage manager, which I had never done before, at the dance theater, the Judson Poets Theater. One of the shows went off Broadway so I went with it. An actor in it was also Merce Cunningham’s archivist, and he asked, “Do you want to work for Merce Cunningham? You’ll be the assistant stage manager.”

STEWART—What does stage managing entail?

CHARLES—You run the show. In dance, it’s really about organizing everything that happens on the stage.

STEWART—You make everything happen.

CHARLES—A lot of artists start out being the subject. But for me, I was never on the performance side.

STEWART—You have such a wonderfully intuitive way navigating the people you put in front of your camera.

CHARLES—I mostly worked with people I know, and quite well. I know what’s appropriate and not. It was also a combination of luck. I didn’t know I was going to meet Bowery or Michael Clark.

STEWART—In my work and even in the way I think about my life, I do stuff with people who I love and like.

CHARLES—In this new show, I’m making a portrait of Lady Bunny, whom I’ve been friends with for 25 years. I wanted to do something with her. In the early days, we used to film at the Pyramid, and she would say, “I don’t want to be filmed.” I would always have to turn my camera off when she came on stage. So she’s been on my bucket list. As I get older I have a bucket list now!

STEWART—What is this show at Luhring Augustine you have?

CHARLES—It’s an eight-channel piece: seven channels in the front room and then one channel in the back. The piece is based on my two years at the Rauschenberg Residency where I was able to think a lot. I’m not a nature person at all. In fact I’m the opposite, so this is really different. It turned into something very structured and mathematical; The title of the show is the Waning of Justice. It’s sort of based on sunset, literal and metaphorical.

STEWART—Where is the residency?

CHARLES—I was lucky. Two years ago they started this residency program at Bob Rauschenberg’s estate in Captiva, Florida. You go for a month. And I collaborated with Douglas Dunn for the first year. Then the next year Michael Clark was invited, and he wanted to work with me too; so I got to come two years in a row. It’s an unbelievably great place. A lot of the footage was shot there.

STEWART—You present your work almost entirely as an installation.

CHARLES—That’s the direction my work has taken. I’ve been doing custom installations for whatever space I’ve been working in.

STEWART—You have a wealth of knowledge and talent of seeing things in space. Don’t you do the lighting design for Michael’s performances?

CHARLES—I used to do lighting design, costume design, and set design. I still do lighting design just for Michael. I did a piece with Douglas Dunn in January where I did the lighting, the costumes, and the video live. I’m also doing this little short film with Michael, and Raf Simons is designing the costumes.

STEWART—That sounds amazing. We talked previously about always having a side job—what I always call a side hustle—to manage your art projects. You used to work the door at parties and clubs in New York back in the day.

CHARLES—That was a low point. After working in Europe for a long time, I felt like I was really becoming a European artist—I didn’t like it. It also was the same time my partner got sick, so I had to come back to New York. I didn’t have anything to do and didn’t have any money. So I got offered a job as a nightclub’s door person. It was cash under the table and a very good rate—quite more than I could make doing anything else.

STEWART—What was your style back then?

CHARLES—This was in the 90s, so I was wearing Vivienne Westwood bondage pants and huge platform shoes.

STEWART—Did you wear a sort of make up?

CHARLES—No, I always go as me. Leigh was one of my best friends, but actually I never dressed in drag. We were going to go out in drag, and he was putting together a drag outfit for me for my birthday. But he died before that happened.

STEWART—What do you think that outfit was going to be like?

CHARLES—Who knows with him! It would’ve been sick.

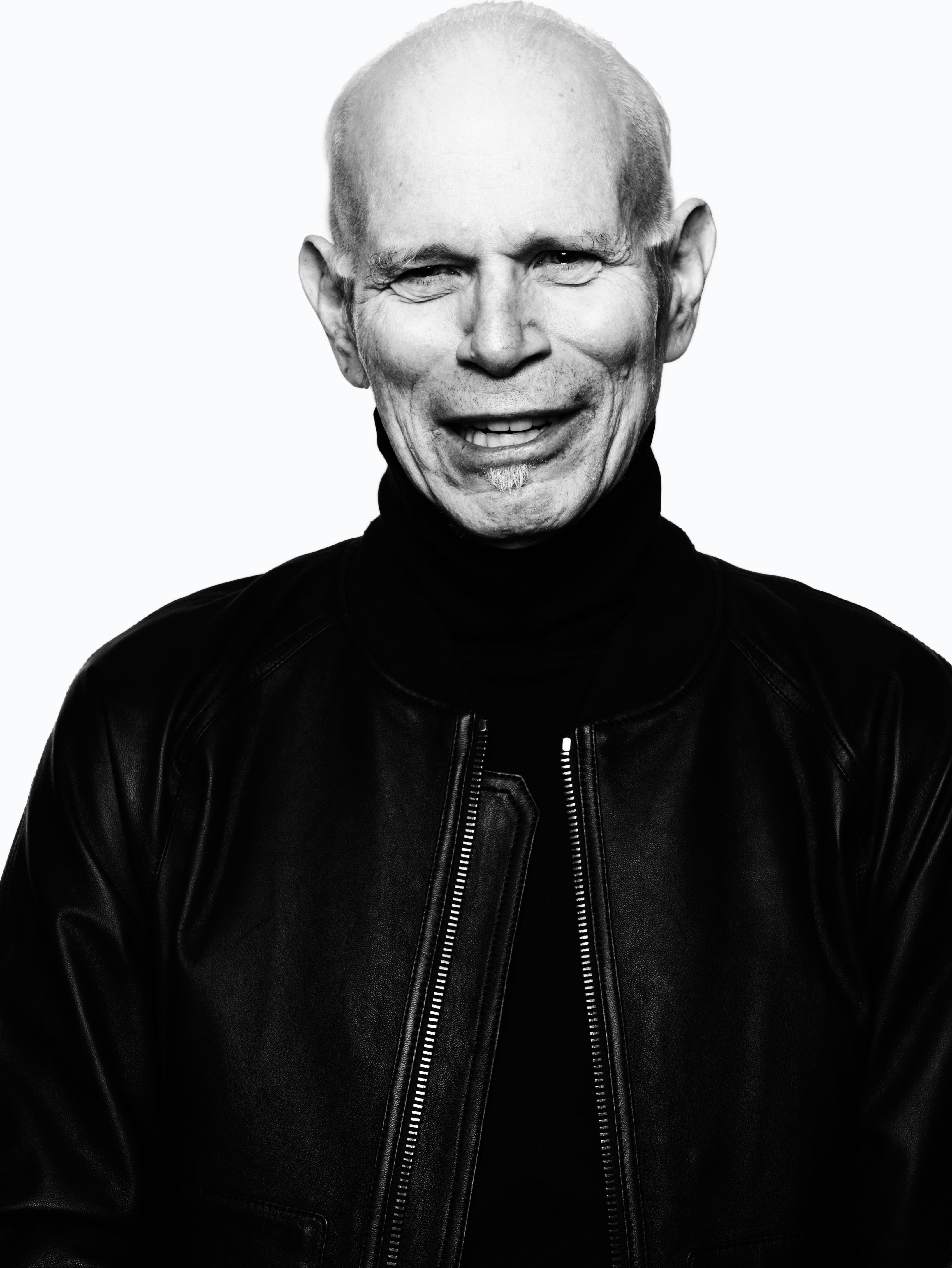

STEWART—How has your process changed over time?

CHARLES—I don’t see any difference. I’m older, I’m more experienced. But when I do a shoot that I organize myself, it’s like doing it for the first time. It’s always overwhelming. For Lady Bunny, I wanted to make a portrait. I wanted her to do a political rant, I wanted her to do a little interview, and I wanted her to do two songs. It’ll be a bit glitzy.

STEWART—You consider your films and videos as portraits.

CHARLES—Yes. It comes from the fact that I didn’t start out in front of the camera myself. In most performance artists’ video, the maker is the subject. I’m not the subject, which is a little hard to get used to in the art world. I’ve always thought that I’m doing portraits, just like Annie Leibovitz.

STEWART—It’s elegant and beautiful about how you’re sensitive enough to create portraits of people you care about.

CHARLES—I couldn’t do a film about a subject that I wanted to criticize. It’s more interesting to spend my time in a positive way, in a positive relationship. I make something that I want to share with people, so I’m enthusiastic. Shoots should be fun. I don’t want it to be a grind because that shows in the final film.

STEWART—You wanna have fun and enjoy.

CHARLES—It used to be really free form, and I’d edit for months to get it into shape. I’m always in control of it afterwards, so whatever problems I make by having fun, I deal with later [laughs].

STEWART—As a rule, that sounds kind of philosophical. You understand your subjects in a very invested real way. You want to share your admiration for having fun with people. You said once that you would want to have a chance present Teach in IMAX 3D.

CHARLES—I saw this documentary about Siegfried and Roy in IMAX 3D and it was the kitschiest most wonderful thing I’ve ever seen. I really wanted to do a film with Leigh in IMAX 3D. I know it’s not possible; I could never get that amount of money. I tried to make a feature film for a couple of years. It just didn’t go far enough; it went up to a certain point and couldn’t get money. I always wanted to do a regular narrative feature, but I never have. I realized I can’t stop my work for years just to do one film, something I’ll still be interested in five years later when it’s finally finished. I’m so used to having an idea and just doing it.

STEWART—It’s a pragmatic issue.

CHARLES—When there’s no encouragement and a lot of debt— those are good signs to do something else [laughs]. I had just had my work in Times Square, which was exciting. I did the Midnight Moment for December 2014.

STEWART—How long was that moment?

CHARLES—It was every night of December for three minutes. You Are My Sister (TURNING) was a video for a song by Antony Hegarty. The images were huge; we had that Google billboard that’s a block long and 47 other screens. It was a little hard to take in. My images were of these Downtown women like Johanna Constantine and Kembra Pfahler, Anthony said it took ten years for us to get from the most fringe Downtown elements to Times Square. Times

Square eventually absorbs everything. In the 70s I used to go to Times Square all the time week to see Hollywood movies in those crummy theaters. Then in 1984, I made a film in Times Square. At that time, there was no light there—none! But now it’s always like daylight.

STEWART—What film did you make there?

CHARLES—It’s called From an Island Summer. It starts out in a dance studio and end up in Times Square. It’s an old thing.

STEWART—I like this idea about keeping footage. You said you used to bring a camera to parties, and you have all of this footage that you could potentially still use.

CHARLES—The only thing about documenting everything is then you have to relive it; to find the good, you know you have to go back in time. It’s better if you focus on what you want to film.

STEWART—When you made Hail the New Puritan, there were aspects that were edited out you wanted to keep in.

CHARLES—The sex scene. We could do anything we wanted, and I was going to do a sex scene. They said of course, if you’re working with Michael Clark there can be a sex scene. They called it a “love scene”. In the rough edit, I made it really raunchy. Then the straight commissioning editor watched it, and they suggested that I take some of it out.

STEWART—You probably have so many things that got edited out from these sorts of situations.

CHARLES—When you’re shooting, you know that it’s not going to make it into the final cut. I actually did one real porno; it was a gay porno. It’s distributed in pornography shops.

STEWART—Is it under your name?

CHARLES—I put it in my book, but it’s not under my name. I did it under the name Jack Shoot. It’s called Staten Island Sex Cult. It was shot in Staten Island in a brothel.

STEWART—Are you friends with the people in it?

CHARLES—I didn’t know them, I did auditions. I couldn’t film my friends having sex!

STEWART—[Laughs] We’re talking about all your obscure works that you don’t even consider work, like your theater thing.

CHARLES—I don’t really have much more to say about gossip than I have to say about intellectual content.

STEWART—My unofficial theme for this interview was “I just want to girl talk with Charles.”

CHARLES—Call me Charlie. I have another ambitious project: I’m doing a residency at Impact, an experimental media center that has amazing equipment and staff. I’m going to do a live-video performance with dancers, which I’ve never done before. It’ll be my first 3D project—with 3D cameras and projection, and six live dancers. I’m working with two different dancers, Silas Riener and Rashaun Mitchell, who are choreographers and former Merce Cunningham Company members.

STEWART—How does new technology affects your work?

CHARLES—I love new technology. Everything I’ve ever done—filmmaking, video, computers—I learned from books. I’ve never had a class or anything like that, but I’m interested in new things. I finally learned After Effects, and I started thinking to myself this is it, I’m going draw the line there, I’m not learning 3D. I have enough for the rest of my life just doing 2D. But last summer, of course I learned this 3D program. I want to do something different—you have to grow with technology. I’ve done everything myself so far. That’s the pleasure, I don’t really wanna be those artist/entrepreneur/ managers. One critic in Europe said my work is a bit artisanal. And I said, “Yes! I like doing the stuff. I like to do the work.”

This article is found in Document Issue 6 out now in select boutiques and newsstands internationally.