Petr Davydtchenko, who’s been living off roadkill as an alternative to capitalism, likens his practice to the bitcoin revolution.

Last Saturday night, in the characteristically tepid Umbrian countryside at this time of year, the artist Petr Davydtchenko was skinning a dead cat. While a silent documentary team watch on, Davydtchenko systematically stripped the meat from the bones, being careful to keep everything intact.

This was part of the opening night of his latest exhibition, Millenium Worm, Davydtchenko’s three year project to see if he can survive entirely on roadkill. The show, supported by the foundation a/political, is held at the Palazzo Lucarini Contemporary in Trevi. The ancient Italian town is host to a challenging documentation of Davydtchenko’s fastidious attempt to find an alternative way of living in the modern world. “I look to find a parallel system, to see if it’s possible to exit the current capitalist system,” Davydtchenko tells me in between preparing some porcupine he found days earlier.

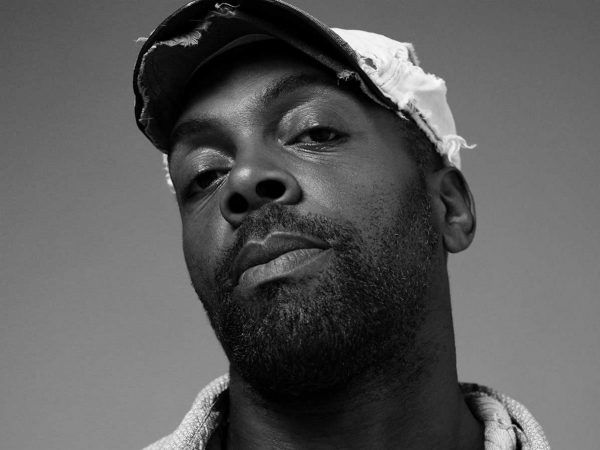

Despite living off animals found on the side of the road, and herbs and vegetables foraged in the wild, Davydtchenko is clearly in his physical prime. At the opening, just shy of 7pm and 13 degrees outside, he was walking around in his signature style; topless with cargo pants and workman’s boots. Tattoos are dotted around his chest, clavicles, and forearms. Three prominent black lines run vertically along his spine, clearly visible at the base of his shaven head.

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Surprisingly, Davydtchenko likens his three years of scavenging from the side of the highway to Bitcoin. “It’s like a cryptocurrency,” he explains. “When Bitcoin was created it was like an alternative to the banks but still using a similar concept. You know the term ‘skin in the game’? The concept for new investors where you put everything on the line—you can lose everything but also win? I have reversed that. I put my life on the line to live by certain philosophies.”

Millenium Worm divides the first floor of the Palazzo Lucarini building into separate rooms, connected by cross-shaped warrens. Each room or section features an uncomfortable video. In one room there’s a video of a dying owl on the side of the road; intact but clearly struggling, the bird silently succumbs to death. In another, there’s an altar where a dead porcupine has been divided into parts, with its quills and flesh clearly separated. As the exhibition continues, there are several confronting sights, where even the hardest of stomachs are challenged. One is a looped video of Davydtchenko eating a raw, dead rat like it’s a chicken leg, the other is under 10 seconds of Davydtchenko putting his penis inside the mouth of a dead fox and vigorously pressing the creature’s head back and forth.

The last video is a surprise to say the least. Not everyone involved in the show knew it would be in the exhibition until the final minute, and when pressed, Davydtchenko clearly wants to avoid it becoming the focus of the show. He says it was a reaction to Fox News doing a segment on him over a year ago. “I just saw the fox on the side of the road and decided to make my own news.”

It’s a departure from the methodical and meticulous approach Davydtchenko prides himself on. Born in Sarov, a closed town in Russia dedicated to nuclear research, Davydtchenko moved to Stockholm as a teenager, where he began his undergraduate in Fine Art before going to Royal College of Arts in London for his masters. Now he lives at The Foundry—an experimental art space in the industria town of Maubourguet in the South-West of France—and is able to spend every day finding and cooking animals that have been run over. “I wanted to sustain myself without buying from supermarkets,” he explains. “To take something discarded by mother nature, and, as I see it, killed by progress. I’m living parallel to progress if I live by taking everything from the side of the road.”

His day to day existence is corroborated by systematic archiving. “It’s in the physical form of a freezer,” he explains, “Which I constantly use.” By logging and storing photographs of his finds, the GPS locations and notes detailing the temperature, how the creature died, what it had eaten and what speed it was hit, Davydtchenko has created an in-depth map of the surrounding area. “I have a very strict routine,” he adds. “I wake up at sunrise, and I cycle out to an area around 30 kilometres around, looking for animals.”

Davydtchenko’s work hasn’t gone unnoticed by the local residents. “Some people come a bring me animals they find,” he tells me as he’s cutting meat. “And some come and find the pets they lost.” He says that, on a few occasions, children have come knocking at his door with posters of their missing pets, only to discover they’re now in Davydtchenko’s freezer. Some of the children are happy to discover their pets haven’t been treated like garbage. “One or two run away but most of the time their reactions are okay,” he tells me when I ask if any are scared of him.

The show’s curator, Maurizio Coccia, says it’s the artist’s discipline and dedication to the cause that takes the work above the level of sensationalism. “I see this practice as being very useful for young artists,” he tells me through a translator. “To have some goal and to have a very rigid way of realizing that.” In a sleepy town like Trevi, the visceral exhibition will certainly be challenging, and even seen as distasteful, to some residents. But both the artist and the curator are quick to claim they’re uninterested in shock value. Coccia explains how most countries eat sex organs in one form or another—“in Naples, in Spain.”

One could certainly envision the Davydtchenko Diet as the logical conclusion of our obsession with all things Instagrammable and sustainably foraged. So maybe the artist’s end goal isn’t as wild as it sounds. “I want to open a 3-star Michelin Restaurant,” he exclaims. “Not just one but three. It’s determination, I will use the rest of my life to get three stars.” The type of dishes he’s become enamored with are still long way off what is generally accepted as high-end cuisine, but they’ll certainly make for good photos. “I think it’s exciting to cook things such as cats and little kittens on the fire, to slow-cook donkey penis with dog testicle, and discover a new kitchen.”