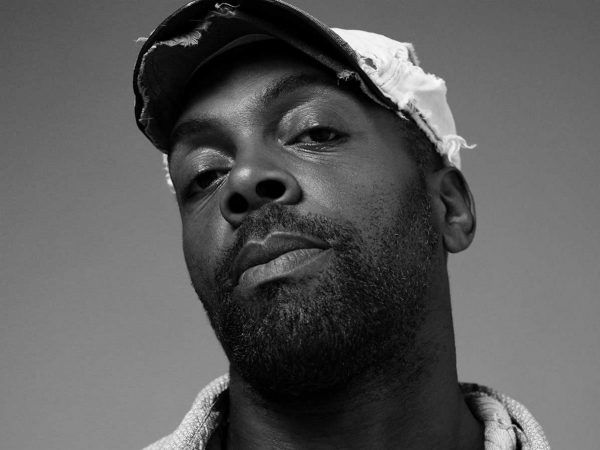

The artist discusses his affinity for parks, creating in the spirit of the internet, and how he's changed since the end of The Still House Group.

I met Jack in early 2016 when I was working on a book project about Tompkins Square Park. We had met at the park and spoke about his relationship to it, and about his art practice. Since then I’ll run into him here and there when I’m out skating or I’ll send him a zine whenever I make a new one. So it was great to meet up at his apartment and speak about his new clothing company, Iggy, and how his art practice has transitioned since the closing of The Still House Group, an art collective Jack and his friends from college ran from the early 2000s to the early 2010s.

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Nick Ricardo—The last time we spoke in 2016, we met up for a project I was doing on Tompkins and my relationship to the people who were in my life—one way or another—through the park, and how that interacted similarly with your film, which is loosely based on that same idea. Can you talk more about that project?

Jack Greer—My Tompkins Square Park isn’t exactly the same as someone else’s Tompkins Square park. If I choose Tompkins and walk into it and I say, ‘What does Tompkins want to give me,’ as long as I’m present and open and focused, I feel like the story will tell itself…. Being a part of subcultures taught me you need to earn the authority to tell a story about any given thing because in many ways, without being a participant, it’s hard to be a critic. In that respect, Tompkins became a place that I spent a lot of time in—as a skateboarder, as a dog owner, as a person in the East Village, and as a resident. So I would socialize, skateboard, go there early in the morning to walk Iggy. At a certain point I wanted to make something out of Tompkins. Time is always in transition, but for whatever reason, I saw the summer of 2016 as an important time to document that space…

Nick—What was it about Tomkins that made you want to document it?

Jack—Parks are a special place for me…as much as I am a journalist and feel that I have the right to document people, you know, part of it is claiming the authority to document people. I don’t believe it’s appropriate to do so in private spaces. Like, I wouldn’t go and film someone in their apartment, or at the bank. There are a lot of places that are not intended for public engagement, and I feel that when you’re in a park, in this egalitarian way, everyone has come together to some extent as a community. It’s not your property—it’s a shared space, so in that regard, once you step into that space, it’s everyone’s.

People have always said, when it comes to downtown culture, oftentimes the people responsible for generating a new scene don’t have the wherewithal—they’re up-close or they’re in it, and it’s only someone who is further removed from it who has the scope to then tell the story or market the story, to capitalize on the commercial possibilities of a scene. When you’re in it, you’re just in it. I find being fully immersed in [the culture I’m documenting] is the only way I personally could feel confident being an artist.

Nick—What really got me into your work years ago when I had just moved to New York around 2013, the Still-house Group was a thing and you were making those collage esque cut-and-sew canvas pieces, alongside your oiled paper works, and then your scarred cactus works and sharpie landscapes. How have these works—all stemming from a visual language you’ve maintained since you were younger making custom-patched denim jackets for example—defined your relationship with the development of your work?

Jack—I always thought that the fly-on-the-wall approach to making a documentary film was the way I would live my life. Do I love fashion? Yes. Do I love painting? Yes. Do I love video? Yes. All these things are in some ways equally important to me…I find that I am capable of telling my story wherever the fuck I end up telling it…I don’t think it’s possible to tell my story with one medium.

I’m a part of a generation over-saturated with information from multiple different access points…watching Netflix on your laptop, watching a movie on your TV screen while you’re writing an essay. The only honest response to that is making work in a similar fashion to the way you ingest information.

It [has] a very romantic impetus. And that is two people, [who have] seemingly nothing to do with one another, both in the park at the same time. Or to have two different people who I feel lucky to have access to—because one’s a musician and one’s a skateboarder—where I can act as a liaison…Finding these opportunities to create these links stems from a desire to support and share what is so special about humanity. There are people out there doing wonderful things—how do we build that into a community?

Nick—After dipping your feet in the pool with fashion or whatever you want to call it, what led you to finally pulling the trigger and start Iggy?

Jack—Basically, I’ve been making clothes my whole life. And when I was 15 I walked into Fred Segal’s menswear department and I was basically like, ‘Hey, can I sell these hoodies here?’ I always used clothing as a one-off scenario because I couldn’t afford to manufacture things—I was young. Then I was able to turn off clothing because I associated it with freelance, with me needing to make money in a creative way, but it wasn’t my profession. I always dreamed of being a studio artist. When the studio art stuff started to drain away and I saw that I was going to need to make money again and not rely on artwork, I immediately said, ‘Oh my gosh, I am not only going to go back to clothing, but even more excitingly, I have actually made enough money as an artist that I can manufacture some t-shirts.’ Which was really just, ‘Hey, I can finally do this.’

Even to this day [my label] is so small. I’d love to be able to do cut-and-sew pieces all the time, and really build out a collection. Hopefully [these pieces] can exist on a scale enabling me to focus entirely on the creative side, and not spend half my day folding shirts to pack them into a bag to ship at the post office. Everything I’ve done has been an army of one. I would love to be able to have a platform where I can tune back in on the creative and be fully responsible for that without all the other shit that comes along with operating a studio practice and a small business. I’m not trying to say I need white glove treatment and people stretching my canvases and telling me what flight to get on, but it’s hard for me to sustain any of the things I do entirely by myself.

Nick—Last time we spoke you said that you think you’re part of the last generation to hammer a nail into a piece of wood, so to speak, with your art practice. What do you think of that statement now?

Jack—Oftentimes, what I’d do unconsciously was put things that were different into a category of being new…I failed to recognize that, in many ways, the table I grew up with was new, and there was another table before that, so things exist in flux constantly.

I no longer think the [generational] hierarchy I once created is necessarily relevant. If one can remove their ego from their time then it’s easier to accept…we often have a tendency to celebrate our own time, and say, ‘Things are so much better when I had them.’ That’s because of the nostalgia associated with youth. I still agree that I can own being the last generation to hammer a nail into a piece of wood. But I no longer think that is any better than, or more important than, someone who doesn’t. I’ve removed my own ego from my experience and accepted that my experience is just as fleeting as [that of] any other generation’s…Nobody can respond to my generation the same way I can. The validity is in telling your story, not creating a hierarchy from your [generation] and other generations.

Nick—So your art collective The Still House Group dismembered—and you are of course still making work, but just not in that studio space anymore. What has changed for you since that dismemberment and how have you maintained your art practice since?

Jack—I got lucky enough to be a participant in a fully functioning system while still operating outside of it, because we didn’t have traditional representation. We didn’t have a gallery. We were direct to consumer. It was the precursor to what exists today with social media—bypassing the old systems in order to sell a product…The idea of a collective wasn’t making collective work—it was a collective of individual artists. The only reason it was a collective and not a gallery was because we didn’t have the brick and mortar and the years to call it so….

The downside of that was that when Still House ended I didn’t have a rapport with collectors and gallerists to go on and transition into something more permanent. Also, [you need to] strike while the iron’s hot. There was a time we were getting hit up to get representation by different galleries for different artists. But, to our demise, we were a little too puffy-chested about maintaining this DIY approach, saying, ‘We don’t need you…’ We didn’t need them when things were flying off the press because the industry was having a market boom, [but] as soon as that subsided we needed the support system of these larger institutions to carry [us] through the lull… if one can be positive about all of this, the work that came into trend afterwards was kind of exciting to me. Everyone under the sun decided they were an artist because it was relatively formulaic and easy to find an algorithm to make something look like art. What was hot in art was purposely minimal simplistic aesthetics. It was all just, ‘Throw my wet toilet paper at this canvas.’

As things shifted [towards figuration], even though I knew there wasn’t going to be a market for me because I wasn’t much of a participant in the industry at this point, I was kind of happy to see more outsider art—more labor-intensive nerd art. More power to [these new artists], because at least the cool kids have to take a break for a little bit. At least there’s room for these people that otherwise really didn’t see opportunity in art to be celebrated, because gallerists and all these evil motherfuckers were going to capitalize on whatever was hot. And if I have to take the backseat for a while I don’t care…I hope that [my work] has another time under the sun but I can’t curate culture. I can’t chase what’s hot. I can only be me and do what I do and hope that the rate at which my funds dry up is not faster than the rate at which the desire for what I do comes back.