Armed with industrial floor paint the artist is working to repair Iraq's bullet-ridden cultural artifacts and reconnect us with our cultural past.

On display in the private residence of the UK’s Ambassador to Iraq, Dr. Salih Hussein Ali, are reconstructions of the destruction done to cultural artifacts at the hands of ISIS. Made from industrial floor paint by the artist Piers Secunda, each work sits alongside a second model, showing the artifact in its undamaged form—before it was embedded with bullet holes and damaged by power tools.

As the first artistic collaboration between the Kurdistan Regional Government’s representation in London and the Iraqi Embassy to the United Kingdom, the display is almost a metaphor for improving relations between the two sides. “ISIS wants to disconnect us human beings from the past,” Secunda explains. “And it’s not just people in the immediate vicinity—ethnically Kurdish or Iraqi people. Their intention is to disconnect people from an understanding of who they are.”

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

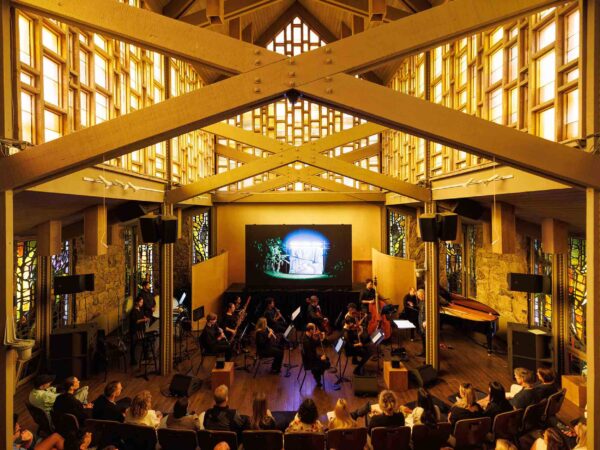

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Cultural destruction has been key to ISIS’s propaganda machine. In 2015, and then again in 2016, the jihadist group blew up parts of the ancient city of Palmyra, with a battle cry to destroy idolatrous art forbidden under its interpretation of Islamic law. ISIS filmed and then distributed footage of the destruction online as part of a worldwide propaganda exercise. “The destruction of culture isn’t purely about people going into museums and smashing objects,” Secunda says. “It’s about destroying people’s abilities to practice the way of life they’ve known for thousands of years.”

The artworks are part of an ongoing series of work exploring culture erased at the hands of zealotry and extremism. Armed with dentist putty, Secunda has spent the better part of the past decade on the frontline of cultural destruction, aiming to “capture the texture of violent geopolitics,” and make an artistic record of what he calls the biggest news story for the past 20 years, if not the last century. The reliefs in Dr. Hussein’s home are the products of two separate trips, one in 2015 and another in 2018. “It’s absolutely essential that it’s recorded and documented in some way which is more than just journalistic and photographic,” he tells me. But traveling to the heart of conflict as violent and dangerous as that perpetrated by ISIS is practically impossible—unless you know the right people.

In 2015, through an academic in Middle Eastern studies, Secunda began building contacts with people connected to Kurdish Regional Government and the Peshmerga security forces in Iraqi Kurdistan. “My contact turned out to be extremely well connected,” he tells me. “When I first got off the plane in Iraq, a representative from the People’s Republic of Kurdistan met me, and took me to an ancient village on an old architectural mound called ‘The Tel,’ near the frontline with ISIS.”

Under the protection of the Peshmerga, Secunda visited Kurdish villages recently liberated after ISIS retreated from the city of Mosul. Despite the villages no longer being occupied, one of the world’s most violent terrorist organizations was a stone’s throw away. A mere 150 yards beyond the Peshmerga border were ISIS-held positions. “They were in very high embankments, fortifications made of clay, that you can’t climb up or you’ll slide back down,” Secunda recalls.

Arriving at 3:00am on day one, Secunda was led to the frontline by 9:30am. On day two, he visited the then-ISIS regional headquarters, a collection of buildings circling a courtyard. Before the insurgency, it had been a school for boys and girls.

Several years after returning from this first trip, Secunda was attending a UNESCO general meeting when he seized an opportunity to introduce himself to Iraq’s Minister of Culture, Fryad Rwandzi, by giving him postcard of his works. “He immediately knew what they were,” Secunda says, “and encouraged me to visit him in Baghdad.” This meeting became the foundation for the artist’s second trip—to Mosul, in March 2018—where he captured damage done to ancient religious artifacts.

The level of cultural destruction Secunda planned to document was more systematic than during his previous expedition. The year after he’d left, the Iraqi government and its Kurdish regional allies had successfully launched a 12-month military campaign to reclaim Mosul from ISIS, who had seized the city in 2014. Secunda was still in a dangerous part of the world: the war to defeat ISIS is ongoing, and a month after the city was declared free, volunteers were recovering as many as 30 bodies a day. But the artist was now able to roam around what was once the administrative heartland of ISIS’s attempt to build its caliphate. “During my first trip to Iraq, it wasn’t possible to go these places because the front line was so defined,” Secunda explains to me. “If you go beyond it you’re exposing yourself to ISS—I mean, that would just be suicidal.”

Secunda’s chief destination was the Museum of Mosul—the second-largest museum in the country—which Rwandzi wanted him to make a record of. In 2015, around eight months after ISIS had taken control of the area, the insurgents had released a propaganda video, later published online, of the group destroying “idolatrous” antiques and artifacts in the museum. targeting any artistic or historical record of gods worshipped instead of Allah. The attack was so savage the museum itself was left a shell of its former glory, with craters in the floor, stairwells left unusable, and holes in the wall.

With a team of Iraqi soldiers at his side, Secunda recorded some of the most poignant and devastating evidence of ISIS’s reign on open society. Assyrian and Akkadian civilizations had existed thousands of years before Christ, and their shrines and statues had, until that moment, literally stood the test of time. “It’s important that artists like Piers show people that what happened in Mosul can happen in other areas too,” explains Rwandzi. Secunda compares the Museum of Mosul expedition to visiting those now-destroyed villages in 2015. Looking into one of the houses, Secunda says, was like peering into a museum of Kurdish life: “There were kilims on the floor, a weaving machine in the corner, a loom, and a baby’s rocking chair.” The destruction is equally significant because all of it impacts people.

“I think the basis of my work is that I’m trying to make a record of the time I’m living in,” says Secunda. “I could take a photograph and put it on a TV screen, but it wouldn’t achieve what I want it to, which is the degree of authenticity that requires careful examination, consideration, and a degree of acceptance from the people who are close to it. Then I know I’ve set out what I intended to.

Since working on pieces about cultural destruction, Secunda has been attuned to the many forms of hidden heritage that’s gets erased around him on a daily basis. In London, Victorian houses get torn down all the time. Secunda says, sitting in his studio space in London, “every time that happens it means we lose a grain of sand from the pile, and that pile is history.”

Later this year, his ISIS bullet reliefs will be traveling to America, and there are plans for subsequent exhibitions. “I want to capture the essence of a story,” he tells me. Just as the molds in the ambassador’s house acted as a bridge between Iraqi and Kurdish relations, Secunda sees his work as an analogy for the ideological adoption of culture: “I want to cross the boundaries of language and create metaphors with my work. When I perforate my castings with ISIS bullet holes, I’m making art which serves as a metaphor for the overall destruction of Assyrian artifacts.”