Drill, juggalos, death metal—studies have shown that listening to violent music can actually make us happy, so why do authorities continue to censor it?

For the past couple of years, London’s Met police in have been waging a war against drill—a type of rap that originated in Chicago but has gained serious traction in some areas of the British capital. Since we covered the issue back in May last year, the situation has worsened. Drill rappers are facing jail time for simply performing their songs, and YouTube has taken down dozens of videos, raising concerns about how the criminal justice system is blurring the lines between freedom of expression and inciting hatred.

Some drill acts have been involved in violence; some used their lyrics to explicitly incite it, and used their music videos to harangue rival gang members. But drill is hardly the sole cause of London’s violence crime problem. And turning it into a scapegoat only perpetuates that problem.

Scientists at Macquarie University’s music lab recently tried to answer the age-old question—do violent lyrics desensitize people? Researchers asked participants to listen to death metal music—specifically, Bloodbath’s cannibalism-themed track “Eaten”—to see if they then became numb to violent images. They didn’t find fans of the music to be any more desensitized than non-fans. “[Death metal] fans are nice people, they’re not going to go out and hurt someone” lead researcher Prof. Bill Thompsons concluded. “If fans of violent music were desensitized to violence, which is what a lot of parent groups, religious groups, and censorship boards are worried about, then they wouldn’t show this same bias,” he told the BBC. “But the fans showed the very same bias towards processing these violent images as those who were not fans of this music.”

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

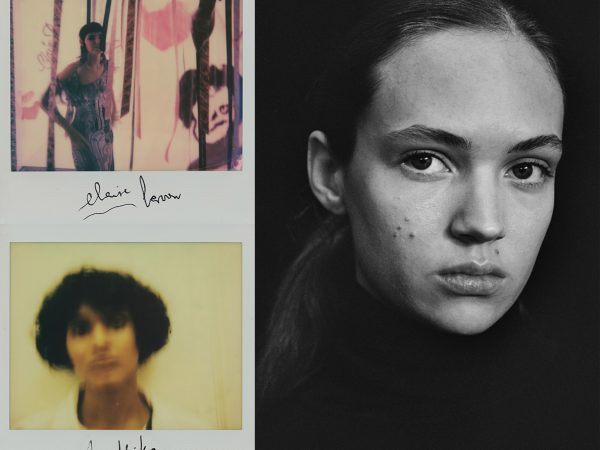

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

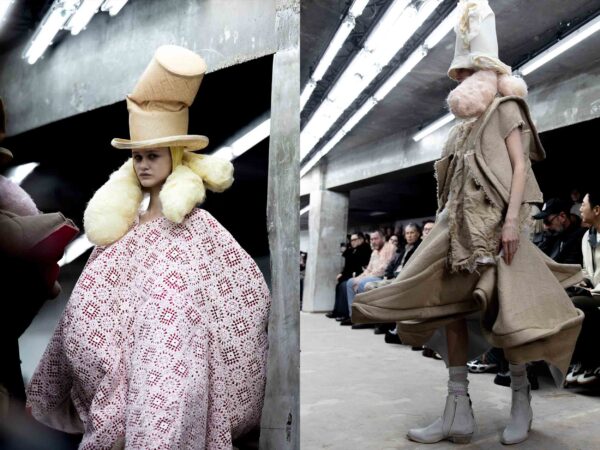

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

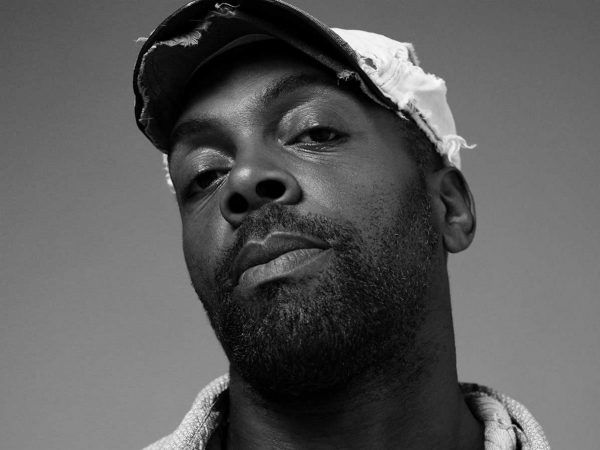

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Serious violent crime in the UK is a real issue; last year it rose 19% across the country and currently, homicides in London are at a 10-year high. The issue isn’t exclusive to the London drill scene. An investigation by British newspaper The Times recently revealed that violent crime in the UK is surging four times faster outside of London as it is inside of the capital, and the UK drill scene, which began in a region of south London in 2012, has pretty much stayed within the confines of the city ever since.

Drill has become part of the moral panic puzzle, perpetuating an old wives’ tale that listening to violent lyrics breeds violent behavior, and steeping it with racial stereotypes. Earlier this month, researchers the University of Missouri in Columbia discovered that pop music is just as violent as hip-hop and rap. They looked at violent and misogynistic lyrics and found that run of the mill pop is a bigger perpetrator. One example they used was Maroon 5’s “Wake Up Call,” a song about a man shooting his girlfriend’s lover after finding them together. “One wonders why pop music is not as maligned as hip-hop/rap for its communication of violence,’ the report commented.

Vilifying one very specific genre of rap isn’t just ignorant, it’s counterproductive. It wilfully ignores facts in favor of prejudice masking as a public good.

When the Met commissioner Cressida Dick asked Youtube to remove drill music videos, it was because she associated their lyrics with the surge in stabbings and murders, and ignored a much wider societal issue. Just over a week ago, Dick was forced to acknowledge a link between violent crime and the reduced number of police officers in the force in a radio interview. “I think that what we all agree on is that in the last few years police officer numbers have gone down a lot,” she said. “There’s been a lot of other cuts in public services, there has been more demand for policing and therefore there must be something and I have consistently said that.”

It looks like the police had better keep their own house in order before they start censoring others.