New legislation brought on by months of public backlash could brighten the future of the Okefenokee Swamp

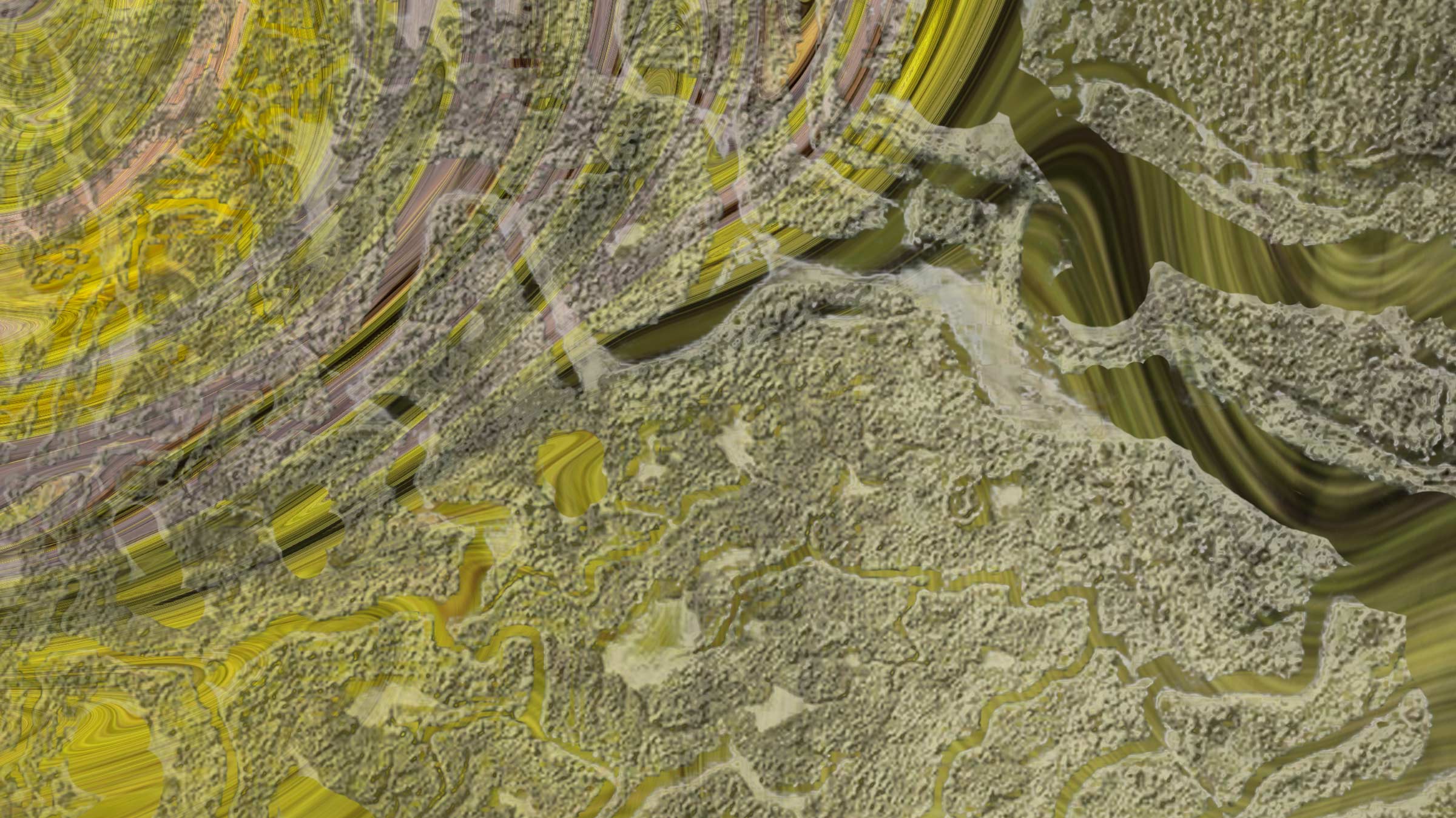

The threat of mining that faces the Okefenokee Swamp, the marshland straddling the Florida-Georgia line, is a small play in a long game of protecting coastal communities. It all started in 2018 when Twin Pines—a mining company that proposed to drill a feature of the swamp rich in valuable mineral deposits known as Trail Ridge—attempted to secure a federal permit to encroach upon wetlands on the property. The interest in mining for mineral deposits—that then could be turned into high-performance chemicals after being sold to multi-billion dollar chemical producing giants—is not unlike that which fueled past waterfront developments seen throughout American history. The sobering reality of anthropogenic sea level rise seen in those coastal communities begs a question surrounding the value of short term financial gain for a few, and long term geographic security for everyone.

Mining in southern swampland began with the Clean Water Act. First passed in 1972 under President Nixon, the act has since been amended dozens upon dozens of times, each change following paradigm shifts in the current politics of the day. Under the Trump Administration, the Army Corps of Engineers changed the definition of which waters were protected under the federal Clean Water Act, effectively removing protection for bodies that once needed a permit to mine, including wetlands like the Okefenokee. The constant shifting of which bodies of water are protected under the act have hindered those trying to preserve the Okefenokee Swamp Park in their ability to combat companies whose work would interfere with the swamp’s ecological vitality.

“Issue lies not in the fact that we are entrusting the protection of the natural environment to the federal government—an entity whose power is at the mercy of a few people’s interests—but more precisely in the way that the federal government can arbitrarily pick and choose which bodies of water have their protection.”

Federal agencies including the Fish & Wildlife Service and the Environmental Protection Agency have expressed concerns about the mining’s impact on the Okefenokee Swamp. And while Twin Pines assures the public that its mining won’t have negative effects, its proposal is fraught with threats to the overall well-being of the swamp and its wildlife: pollution in streams, lower water levels, and the potential for light pollution interference.

Issue lies not in the fact that we are entrusting the protection of the natural environment to the federal government—an entity whose power is at the mercy of a few people’s interests—but more precisely in the way that the federal government can arbitrarily pick and choose which bodies of water have their protection.

Twin Pines stated in 2020 that the company would no longer need to pursue federal permits for its project, and would proceed in securing necessary state-issued permits to begin operations. The massive response that followed brought to light the impact of public opinion, as well as the delicate financial future of the Swamp. Rena Peck, Executive Director of the Georgia River Network, remarked that, “During the course of the permitting process, which allows for review by federal and state agencies as well as the public, some citizens sent 60,000 letters and e-mails to the US Army Corps of Engineers voicing opposition to the project.” The unprecedented public attention on the swamp came as a result of a lack of federal oversight.

The team at the Okefenokee Swamp Park—along with outside organizations including the Southern Environmental Law Center and the Georgia Conservancy—took initiative then to study the environmental effects of the proposed mining. More and more public parks have begun to independently study environmental changes in their own facilities, but this kind of programming takes money and the cooperation of people from different organizations. Guaranteed protection by the federal government would eliminate the need for such drastic measures to take.

This week, however, in a promising move, the Georgia legislature introduced a bill with bipartisan support that would prohibit the state Environmental Protection Division from issuing new mining permits for Trail Ridge. This bill wouldn’t stop Twin Pines’s mining permit from potentially being approved, but with a vow from Chemours—a performance chemical producing giant—to not purchase titanium from the Twin Pines mining project should it go through, small wins are occuring in the effort to preserve coastline communities.

The destruction of the southeast marshlands will compromise the sanctuary of central cities in Georgia that, in the next century, will be a prime location for ecological refugees. This, of course, is all dependent on the vitality of our marshlands.