In ‘The Quickening,’ Elizabeth Rush contemplates parenting and procreation amid Antarctica’s rapidly vanishing ice sheets

In 2019, 27-year-old Mumbai businessman Raphael Samuel pulled an unusual stunt: He announced his intention to sue his parents—for giving birth to him. “It was not our decision to be born,” he told the BBC. What seemed like performance art soon ossified to political statement. Samuel is a self-described “antinatalist”—a philosophical consortium who believe procreation is ethically unjust—and their movement may be gaining steam.

A recent study hints at growing antinatalism in Europe, with groups like BirthStrike gaining mainstream coverage while organizations like Conceivable Future draw attention to the peril of childrearing amidst our eco-crisis. Just last month, the New York Times published an array of harrowing statistics: In 2020, the U.S. birthrate declined for the sixth consecutive year and one-in-four would-be parents now cite climate change as a reason to forego child-rearing; this past June, a global survey revealed that 91 percent of parents are worried about climate change—with 53 percent of those parents saying climate change will affect their decision to have more children.

We’re not equipped to deal with the end of the world, and as wildfires rage across the Americas, global sea levels rise, and people migrate from their once habitable homes, neologisms like “eco-anxiety” and “climate grief” continue to pierce the cultural lexicon. Look around you: Are Samuel and the natalists on to something? In the absence of coordinated, collective action, are our only choices individual ones?

These are the questions the writer Elizabeth Rush contends with in her latest book The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth. In it, Rush meditates on the lure of motherhood aboard a scientific research mission to Thwaites, a broad and consequential glacier rapidly melting on Antarctica’s eastern coast. Thwaites’ collapse will have devastating global repercussions. (“Will Miami even exist in one hundred years? Thwaites will decide,” she writes.)

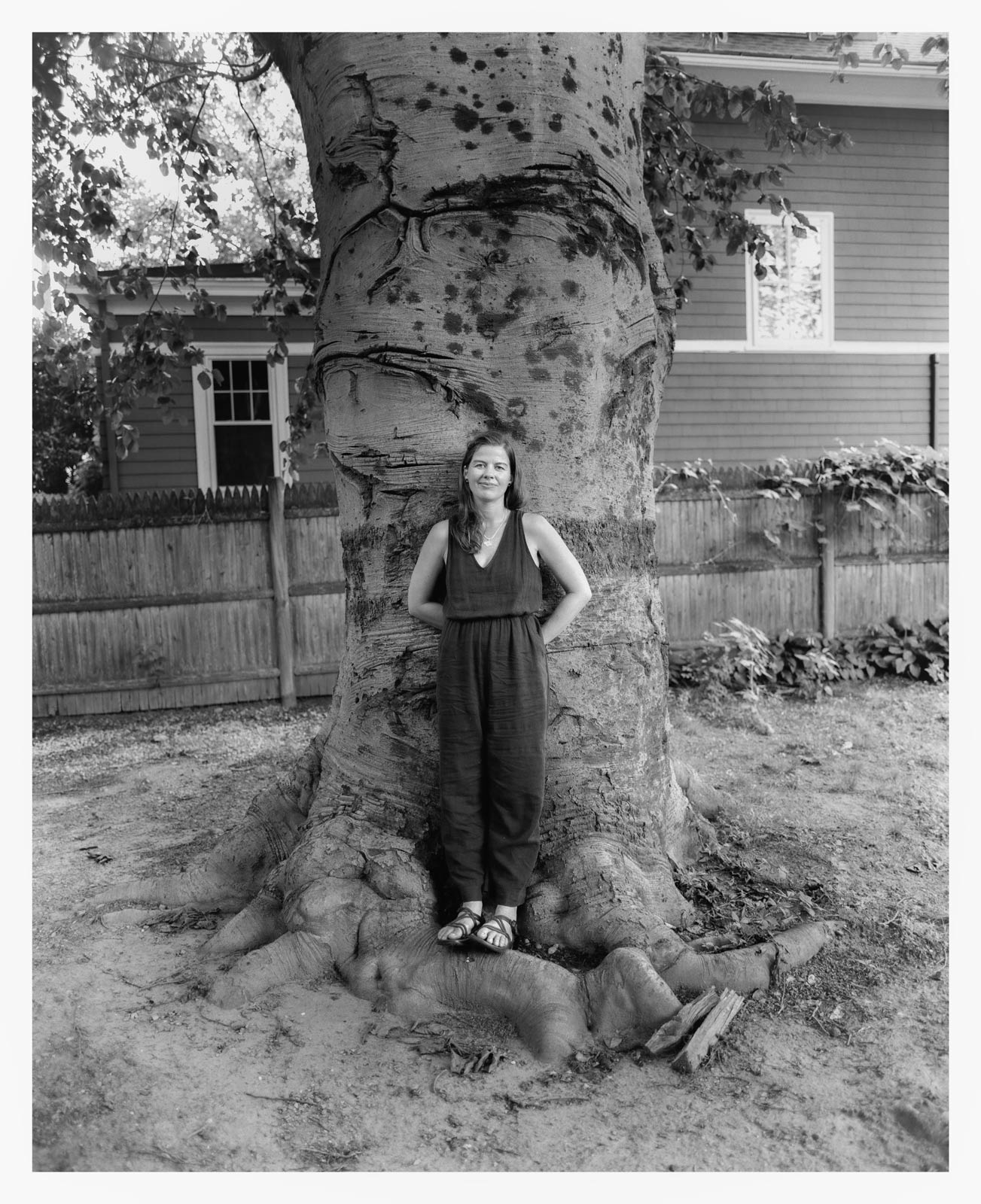

In July, I traveled to Rush’s home in Providence, where I was greeted by the writer and her three-year-old son—her “book baby.” Under a 200-year-old beech tree in her backyard, we discussed Thwaites, climate change, and the consequences of what we bring into this world.

Alex Hodor-Lee: You boarded a scientific and research mission to Thwaites—the so-called ‘Doomsday Glacier’ of Antarctica. Was the expedition a success?

Elizabeth Rush: Yes. We were the first people to ever make it to the calving edge of the Thwaites glacier, where the glacier discharges ice into the sea. [Researchers] have tried to go back every year since—except for the pandemic year—and they haven’t been able to. We’re still the only people that have ever been there. The data we gathered is the only data we have from that particular place.

Alex: You detail how we’ve traditionally viewed Antarctica as this ‘virgin territory’ in need of conquering, full of metaphors of sexual dominance, and you’ve sort of upended that narrative. For you, Antarctica is a place where life begins, not ends.

Elizabeth: Yes. I remember going to the library and being surprised at how small the Antarctica section was. The first person to see Antarctica saw it in 1820. So, every first-person account we have of it is written in the last 200 years, and those 200 years of human history are years of imperialism and capital extraction. That’s a story woven into almost every narrative account of Antarctica. [It’s] the same half-dozen stories—[Roald] Amundsen’s conquest of the South Pole, [Robert Falcon] Scott’s death trying to conquer the South Pole on his return, [Ernest] Shackleton’s expedition and miraculous return, [Douglas] Mawson shooting and eating his own sled dogs. I was very quickly super bored.

Alex: There even seems to be an obsession with recreating those voyages.

Elizabeth: Yes, last year everyone was like, ‘Wow! They found the Endurance.’ Can we stop caring about the Endurance? It’s a cool story, but it’s not the only story.

When we set out, there were also two men trying to ‘solo trek’ across the continent—I was very frustrated by that. They were not doing it alone! There [was] such a network of support behind them. I think that’s part of what irked me on top of all the metaphors of sexual dominance, which also really irked me. No one accomplishes anything difficult in isolation. I knew I wanted to push against that narrative.

While I was getting ready to go on this mission, I was also wanting to have a kid—I literally had to postpone having a kid to go on the mission, [because] you’re not allowed to go to Antarctica on a government-sponsored mission if you’re pregnant. I saw those two things that have historically been kept really far apart from each other commingling in my life. And I thought, What happens if I don’t keep motherhood apart from Antarctica? I wanted to go on the expedition with that in mind. It became about [as I was] thinking about Antarctica as a place where life begins, thinking about Antarctica as shaping us, and not just in negative ‘doomsday’ ways. Thinking about it as being central to the human project—even though we keep it separate from us.

Alex: Antarctica is life-giving, not life-taking.

Elizabeth: Exactly. It’s not this barren outpost at the end of this earth. [I asked] the chief scientist on board, ‘Do you think Antarctica shapes us?’ He thought about it, and said, ‘Yeah, Antarctica’s exceptional stability over the last 6,000 years literally gives rise to coastal civilization. Our human society wouldn’t look anything like we know it to be without Antarctica’s stability.’ He also said: ‘If you step outside of those 6,000 years, sea levels rise five [or] six feet a century all the time.’ We talk about that in this century as being a really catastrophically high number—that’s actually pretty average. The exception is how stable it has been. It’s interesting: It creates this really direct link between Antarctica and us.

Alex: You’re very generous in handing over narrative shape to your protagonists—they almost narrate the book alongside you.

Elizabeth: I was on the boat, and I knew that I didn’t want to be the sole narrator of this story. In all of these stories of conquest, it was one guy on a big expedition. So I knew I couldn’t do that. I learned that from [my book] Rising. The things I liked most from Rising were when other people were talking directly to the reader. I did a daily interview practice on the boat: I got 33 of the 57 people on board to participate [and] probably did four interviews a day.

The process determined something—when I sat down to write, I wanted them to speak directly to the reader, [so] I formatted it like a screenplay [where] the interviews dictated the play in four acts—I wanted it to have a big thrust. Some part of me wanted to use the adventure to create the big narrative arc of the book: It does, but the pregnancy story bizarrely [has] more energy around it than the Antarctica story.

“Everyone asks, ‘What should we do?’ I say, ‘Just do something.’ Get together with other people. Join an activist group. Do citizen climate science. Carve out a space in your life where you’re actively doing something about it.”

Alex: But it also accomplishes the central idea that one story cannot live without the other.

Elizabeth: Yes. They’re deeply intertwined.

Alex: You’re in the vanguard when it comes to understanding climate change—and it doesn’t look so good. I often feel like writing about climate change, if it doesn’t solve the problem, somehow makes it endurable.

Elizabeth: Totally, I think that’s really true. If I’m being perfectly honest, I was always interested in writing about the more-than-human-world, or nature—it felt like a space where I didn’t have to be any way for any person. I got to have more unmediated experiences. The more I learn about nature, I think that’s all contrived. No one is ever walking through the forest by themselves, that was the first allure. I wanted to keep having those kinds of experiences.

I started to write about sea level rise because I could see climate change manifesting now—ten years ago, it was harder to feel. The wildfires weren’t happening, the torrential rain wasn’t happening as much. It felt like an immediate way to have something to say that also brought me into conversation with this longer, deeper passion [for] writing and being in nature. Now that I’ve been doing it so long, [writing] absolutely makes climate change feel endurable because it’s getting worse and worse. A lot of people are waking up to their climate grief.

Everyone asks, ‘What should we do?’ I say, ‘Just do something.’ Get together with other people. Join an activist group. Do citizen climate science. Carve out a space in your life where you’re actively doing something about it and it’s way more endurable—I think it’s not doing anything that feels really hard.

Alex: Is motherhood one of those things? A form of climate rebellion?

Elizabeth: Motherhood makes you commit to a livable, more just future in a way that feels more immediate and necessary. It takes away the free time you have [laughs]. You definitely lose some flexibility in that arena, but it turns up the dial on the urgency.

Alex: There’s so much personal cognitive burden involved in climate change. How do you make the leap of faith into motherhood, even knowing all you know about climate change?

Elizabeth: It’s really hard, I’m not sure I have an actual answer. In some ways, that’s part of what the book tries to wrestle with. I went into the expedition wanting to have a kid. I thought, Is this expedition going to take that desire away? I didn’t feel that desire waver or shift at all—and I was shocked by that. I wondered if I would not want to become a mother by the end of this project, then it became hard because even though I know deeply what climate change science says about how our future is becoming more unstable and unjust—it did not go away. I have to live with that. I have to look at my son and say, ‘I brought you here.’

There was one piece of information that shifted how I felt: learning that the fossil fuel industry really popularized the carbon footprint. All of that is a really savvy way to blameshift corporate accountability for our climate-wrecked future. That’s true on a meta level, but it functions in each of us every day at the grocery store when we ask [ourselves] if we get the tomatoes in the plastic container from New Jersey or the ones in the paper container from Washington—you’re trying to figure out what the right answer is. The point is not that there’s a right or wrong decision; the point is that you’ve wasted energy that you could have put somewhere else—maybe organizing with other people to slow the combustion of fossil fuels. Any guilt or shame I felt morphed into rage when I learned that. I’ve lost years of my life wanting to feel bad about having a kid, and I’ve been taught that by the industries that want to keep making money, so much so that they’re willing to affect women’s reproductive decisions. So, fuck you! [laughs]

Alex: I remember learning that and thinking, Holy shit, I can’t believe this problem that needs collective action has been fobbed off as personal responsibility. But, also, in defense of individual responsibility—as Americans, we have done more to accelerate climate change than anyone else…

Elizabeth: Totally. I’m not here saying we need to consume less—[which] we do.—but we can’t just get our houses onto solar. There is an expectation of getting everything new and getting it now that has permeated our lives. I do think cultural value does have to shift away [from that]. I think that’s happening at an intergenerational level. My generation and the one below me—I feel like we’re less materialistic than my parents’ [generation].

“Part of democratizing [the climate] conversation is acknowledging that climate change is a sickness in our society. It’s not just parts per million in CO2, it’s wondering how you live in a deep and meaningful way with more than human actors around you.”

Alex: You keep mentioning action and activism, but you don’t bring too much politics or policy into The Quickening, and there’s really only one moment where activism creeps into the book—why do you eschew those things?

Elizabeth: There was a period while writing the book where I thought that activism was going to be a bigger part of the post-expedition narrative. I came back from that expedition and got involved in an activist organization in Rhode Island called Nationalize Grid, which appears in the book. The whole movement of Nationalize Grid was to take public control of the public utilities in Rhode Island. We have the third-highest electricity costs after Hawaii and Alaska, which is kind of crazy. I thought this would be a big thrust at the end of the book, then the pandemic happened and I gave birth. That whole universe—it felt like there was all this momentum around climate organizing that got completely swept off the stage by the pandemic. The Sunrise Movement and Fridays For the Future—it felt so propulsive and then it disappeared. It disappeared from my life for all the reasons that it disappeared from a lot of people’s lives. And I had a kid. It comes up in the book but it doesn’t stick around, that’s reflective of what happened.

I made a choice in this book not to make politics front and center. I was trying to write the activist narrative as it was happening, and I struggled with it. I felt that other people do that writing better than I do. You don’t need me to do that writing; you need me to do something else. I made a decision not to write about it because it’s not my strength as a writer, and because it alienates a lot of readers. It kicks people out who feel judged for not doing the activist thing. With this book, I was always trying to imagine an audience that’s more ample than the traditional environmental audience. If I could get stoner dudes who want an adventure story to read this book then I’ve won.

Alex: I saw you retweeted Kerri Arsenault last month. She said: ‘I try to avoid divisive political or activist narratives that condescend to underserved people. What if we immerse readers in slowness rather than the spectacle of disaster?’ Those political or activist narratives can really bounce a lot of readers out of your writing.

Elizabeth: I love Kerri. She’s from this town that’s fundamentally shaped by the paper mill and her dad and grandfather work in it. She writes so well about how people want to assign blame to communities as polluters, but it’s so much more complicated than that. I’m always interested in highlighting stories from voices that [don’t usually] get the microphone. That’s a nice way of thinking about why I don’t make politics so central [in my writing]. Those guys get a lot of airtime. I don’t need to give you more.

Alex: Do you see where climate writing is going? There are all these new voices finally getting the chance to write about climate change. And it’s not the traditional, world-on-fire writers.

Elizabeth: The conversation is becoming more democratic, ample, and open. People have perspectives on climate change that might be about land use or toxicity or indigenous land rights, for example. Those are all climate questions even if they don’t code as traditional questions about carbon offsets.

Part of democratizing [the climate] conversation is acknowledging that climate change is a sickness in our society. It’s not just parts per million in CO2, it’s wondering how you live in a deep and meaningful way with more than human actors around you. Those are questions tied to slavery and colonialism—and climate change is in there—but we need to think about it in more ample ways.

“The world has ended many times before. The indigenous habitants of the Americas—colonization pushed them to the edge of extinction, fundamentally causing language to be lost and species to be lost. This is not the first rodeo.”

Alex: In The Quickening, you write: ‘Ours is an age of loss.’ What are we losing?

Elizabeth: What are we not losing? I fell down this massive [research] rabbit hole that doesn’t show up in the book. I spoke with a sea turtle researcher who said the sex of a sea turtle is determined by the temperature at which the egg is held during the second trimester of its incubation. She went out to her field site and started to sex the hatchlings of the last five years and she told me it’s 99 percent female to one percent male. I just got goosebumps. Climate change is intervening and will fundamentally cause the collapse of the sea turtle because of such narrow margins of warming. It’s called phenological mismatching, like having flowers bloom in March instead of April. Bumblebees show up in May, and can’t help flowers reproduce—flower populations are collapsing because they’re not able to time their blooming to the arrival of bumblebees. That’s a climate change thing but it’s also a toxicity thing—it’s really recent that human beings get to choose to have a child or not. The pill was made available in the ’60s. We think of climate change and reproduction as a choice, but there are many species for whom it is not a choice. Climate change is fundamentally upending reproduction. So our’s is an age of loss.

Alex: In the end, what makes you hopeful?

Elizabeth: The world has ended many times before. The indigenous habitants of the Americas—colonization pushed them to the edge of extinction, fundamentally causing language to be lost and species to be lost. This is not the first rodeo. Somehow I take solace in that. Everyone needs to move through grief. I’m not saying, Get over it, you need to be there and dwell in it. But I feel less grief-stricken—even though the news has gotten worse since I started covering this beat—in part, because I’ve gotten to some level of acceptance, and also [have] a belief that we can get together and change some of the ways we live.

I think of climate change as gifting me that community I got on the boat, and I wouldn’t be who I am without it. The opportunities are there—and sometimes they feel easier to seize than others. Even watching people pay more attention to the world around them—my students over the past 15 years have gone from being oblivious to way more attuned to the world around them, and that’s the place from which action really begins. It’s easy to forget that change is happening—and not just change for the worst.