The Greek photographer reflects on the shift from documenting nightlife hedonism to capturing queer intimacy in his largest exhibition yet at Berlin’s Rosegarden

In the summer of 2021, as lockdown restrictions eased in New York City, I was diverging from my pre-Covid life—my old friends, my old apartment, even my old name. I was in early infatuation with a lover who had just moved to the city from Berlin. He is an adonis, a classic beauty, as though pulled right from an ancient Byzantine coin. He introduced me to his friend group and their nocturnal lifestyle of glamour and excess, one that I had not yet considered a possible reality.

One afternoon, I was in a Crown Heights apartment at my very first afters, techno thumping out of monitor speakers flanking decks in the living room. The cover of an artbook on the coffee table caught my eye—two boys locked in an embrace, their kiss concealed by a shirt wrapped around their faces. It was Spyros Rennt’s Lust Surrender, cover-to-cover with raw semi-nude photographs of tattooed guys necking at apartment parties much like the one I was in.

“Do you like the book?” my lover asked. “The photographer is my friend. Many of the people in that book are my Berlin friends.”

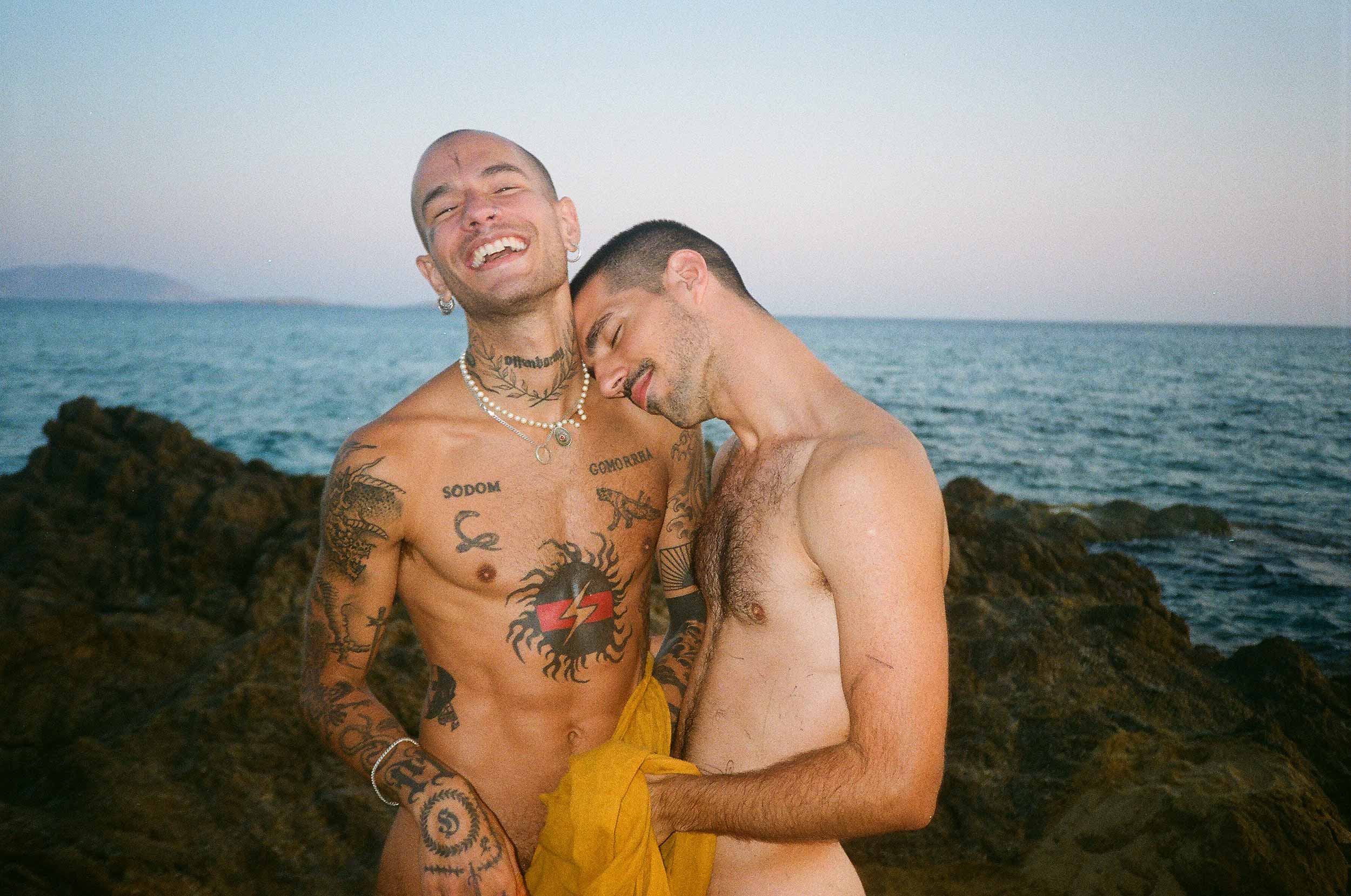

I didn’t know it then, but the book was a visual manual to the life of velocity I was entering. There is a universality to Rennt’s pictures. He depicts a global hedonism by photographing models from a social scene that webs across Berlin, New York, Paris, and other metropolises. Rennt masterfully distills the intensity of these relationships, built over sleepless weekends, in candid captures—as seen in his coverage of Whole Festival for Document last summer. A fevered intimacy, whether connective or fractious, is inevitable after spending 48 consecutive hours with anyone.

Now, in the spring of 2025, Rennt has unveiled his latest exhibition, To Kiss Against the Fire. On view through May 30, it’s the inaugural show of new Berlin cultural space Rosegarden, and Rennt’s largest to date, spanning four monographs and eight years of work. Here, Rennt turns his lens from gay sexuality and excess to queer sensuality and intimacy. As political headwinds grow stronger against queer communities worldwide, the exhibition arrives at a critical time.

“My work is very much looking inside at what community, close friends, and lovers can do to protect us,” Rennt explains. I got to speak with him at a moment of mutual reflection, as both of us—gay men who grew up in Mediterranean cultures (Rennt in Greece, myself in Lebanon)—look back on our parallel journeys, starting with the radical act of claiming gayness in our youth to now embracing more fluid, expansive queer identities.

Adnan Qiblawi: Are you still a part of the nightlife community which you photograph?

Spyros Rennt: If I compare to myself 10 years ago, not as much, but I’m still present sometimes. For me, a night out is going to spill over to the next day, so I need to have a very planned schedule, because otherwise, I really hate myself and the decision. But nightlife is such a part of Berlin, and for me in particular because a lot of relationships have been built there. I can’t imagine myself being completely detached from it. I moved to the city because I wanted to experience that.

Adnan: How would you say your practice has evolved from being a nightlife photographer to now?

Spyros: I think it just organically transformed. I still will do the afters, but because I don’t party so much anymore, when I do, I don’t want it to be connected to me producing work. The archive is already rich. I might still have my camera, I might still take a photo or two, but I might not be releasing these images so much. If you only do that, it becomes one-note, and I’ve already had to deal a lot with being put in the nightlife box, the queer box, all of these things.

Adnan: How would you say this show now is different from then, similar from then, and what is the thread that connects?

Spyros: I wanted it to be more intimate and sensual, as opposed to excessive and sexual. Intimacy and documentation of closeness and community are things that still attract me, so I wanted to focus more on these aspects.

Adnan: In your own personal life, do you feel like you’ve shifted from sort of a life of excess to something more intimate? Are you an intimate person?

Spyros: I’m definitely an intimate person, but it’s not that I wasn’t an intimate person before. I was just interested in photographing a different aspect of my life.

Adnan: Is it a function of age at all? I mean, some people can do excess forever, I certainly feel different from five years ago. I was always a very intimate person, but in a period where I was focused on excess. Now I just can’t see myself doing things at that level. Do you think you relate to that?

Spyros: Totally. There are no naked men in my show now because I knew if there were, people would concentrate on that. My archive is always there—if I want to go in that direction, I can always do it by editing the work accordingly.

Adnan: Some of these pictures are older, right? In the exhibit?

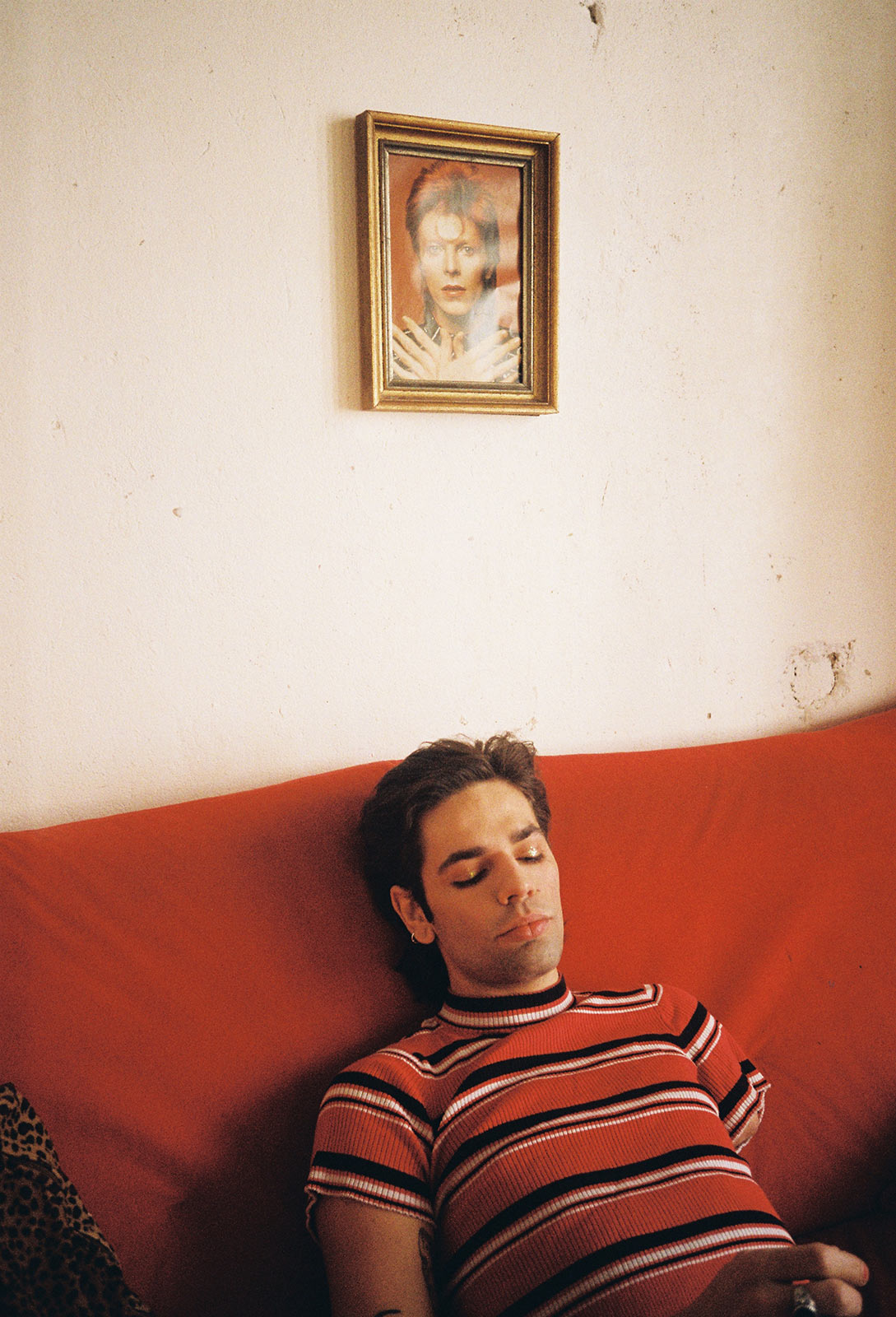

Spyros: They’re photos from around 2017. It’s all a matter of edits, what you want to say. A quieter image can actually be louder this way.

Adnan: And what do you want to say? Because you said you’ve been put in this nightlife box and this queer box, but this show has been described as very much a queer show, a political show.

Spyros: The queerness is still, especially in 2025, definitely something important. I would say it was the gay box, which is something I’m not really standing behind anymore. When I started, besides nightlife, I was also shooting guys, and I’m not really so interested in that anymore. The queerness definitely interests me, but the gayness, the gay aspect—I just don’t really vibe with that gay, male-centric kind of work.

Adnan: You’re placing this show in the context of 2025. Can you tell me more about that, about its relevance at this time as a queer show?

Spyros: It’s not a very good time for queer individuals in general. This documentation of queerness is something I’ve always done because we were always a minority. In previous years, there were glimmers of hope that we were entering the mainstream and things were looking up, but I don’t think we’re there at this point.

Adnan: When you say we are a minority, you also mean we’re a marginalized minority.

Spyros: I grew up gay in Greece.

Adnan: I’m from Beirut, Lebanon.

Spyros: Exactly, so you get it. That’s the experience—marginalized. My work has always been about the visibility of our community.

“It’s all a matter of edits, what you want to say. A quieter image can actually be louder this way.”

Adnan: In 2025 specifically in Germany, what is happening? Can we connect what is happening in Germany to what is happening in America?

Spyros: I made this show with more of a global audience in mind. The news from America and the UK, they make waves here [in Germany] and influence the politics. I don’t think this timing is coincidental—like the law that got passed in the UK two weeks ago, and we’re just waiting to see what happens in Europe. It’s a tricky time in general. My work is very much looking inside at what community, close friends, and lovers can do to protect us and be a refuge.

Adnan: Are most of the people in the photos friends and lovers?

Spyros: Friends and lovers, but not only. It’s community—not necessarily just the community of Berlin. It’s also people from Greece, people I shot in New York. The location is not so important for me. My work in general touches on this effect of globalization, in the sense that you look at a photo and think, “Is this an afters in New York, or is it in Berlin, or maybe anywhere?” Does it matter? We party and entertain ourselves in similar ways at this point.

Adnan: The interesting thing about the location is that it’s universal—whether this was taken in Berlin or New York or Athens, it’s kind of all the same—it could be anywhere.

Spyros: Exactly.

Adnan: Do you have a favorite artwork in this exhibition, or one that’s the most special to you?

Spyros: I’m happy with, “After Hours Kiss,” the one with the two boys on the red carpet. That was an image from 2018 that still feels very current. One of them came to the show and was very happy. A lot of the people who were in Berlin who were featured, they all managed to be at the show.

Adnan: It’s a timeless moment, really. The afters make out on the floor—it could be seven years old, it could be 50 years old.

Spyros: Exactly.

Adnan: I lived that similar kind of Mediterranean social background—the navigation of growing up gay. I’ve been in New York for 12 years now, so I have an idea of what it’s like to be gay there versus here. And I understand the need to hold on to the gay identity at first and what it means to then transcend to queerness, something more fluid. That narrative is something I can immediately relate to.

Spyros: It’s nice to talk to someone who understands. When I was growing up, queerness was not part of the lexicon, and gayness was radical. Now, at this point, we can definitely distinguish between gayness and queerness.

Adnan: It’s a past life.