Peaches, Liz Johnson Artur, the infamous Berghain bouncer Sven Marquardt, and others share their memories of an international turning point in Document's F/W 2019 issue.

This article will appear in Document’s upcoming Fall/Winter 2019 issue, available for pre-order now.

Is there any place more evocative of the 20th century than Berlin? For countless generations, the city’s sense of time and place has had a quickening effect on the pulse that has made it a byword for experimentation and reinvention. Christopher Isherwood captured the hedonism of the Weimar-era city in his novels, later immortalized in the musical Cabaret; David Bowie captured a 1970s Cold War foreboding in his trilogy of expressionist albums, Low, “Heroes,” and Lodger. The city was always fearlessly about sex. “To Christopher, Berlin meant Boys,” as Isherwood wrote in his memoir, Christopher and His Kind. Today, clubs like Berghain continue to fly the flag for openness and tolerance.

Imagine a city that is also a kind of prison. In 1961, when a cinder-block wall, barbed wire, gun placements, and watchtowers sprung up overnight, that’s what Berlin became. Friends were divided; families were sundered. The Berlin Wall was the cruelest and most visceral emblem of the Cold War—a locus for spy novels and Hollywood thrillers, but with real-life consequences. Several hundred people would die over the years trying to cross the no-man’s-land that divided East and West, and in 1983 the Wall was a literal flashpoint for a nuclear showdown after a series of NATO war games. A German psychiatrist noticed so many more patients with chronic anxiety that he coined a term for it—Mauerkrankheit, or wall disease. That’s what living in prison can do to you.

But West Berlin was also a kind of sanctuary, heavily subsidized by the state, and a magnet for artists and dropouts who turned the city’s splendid isolation into a virtue. People who lived there could get exemptions from mandatory military service. And the more existential life feels, the more likely you might be to lose yourself to the sound of the beat.

When the Wall came down 30 years ago, on November 9, 1989, it heralded the end of the Cold War and the reunification of Germany. It was the beginning of the most optimistic era since the Jazz Age of the 1920s, a time of economic prosperity and increasingly liberal government.

When Ronald Reagan visited the city in 1987 and made his famous speech at the Brandenburg Gate—“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,”—it felt like so much chest-thumping. Few could have imagined that his vision would so soon come to pass, although in hindsight it now seems inevitable. But as the visual artist and choreographer Anne Imhof observes, the Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe in 1986 was a harbinger of the USSR’s collapse. From that point on, it was a question of when rather than if.

In the now hollow words of Francis Fukuyama, the end of the Wall was also “the end of history,” meaning that the West had won the battle of ideas. There was a period when it seemed that Fukuyama must be right. Anyone who remembers the ’90s can recall the sense of expanding horizons and rich new possibilities. Everything was getting better, until it wasn’t.

Berlin is a different city now—the discrepancies between East and West largely erased, tourists everywhere. Checkpoint Charlie, the famous crossing point between the two halves of Berlin, is now a tourist attraction where you can buy a tiny piece of the Berlin Wall for 26 euros. Yet there is still no other city that feels as freighted by the burden of history, or as shaped by the tumult of politics. You can’t turn a corner in Berlin without being confronted with the dramas of a century of history, whether it’s the rebuilt Reichstag or the East Side Gallery—where a mile-long remnant of the Berlin Wall stands as a monument to the folly of walls and the precariousness of peace. Here, some of our favorite artists share their memories and thoughts on the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, and why it still matters.

Eugene Hütz: The Berlin Wall Was a Major Pain in the Dick.

As frontman to the “Gypsy punk” group Gogol Bordello, Eugene Hütz gives a bombastic, joyous performance and, an exultant middle finger to the Soviet austerity of his Ukranian childhood. A descendant of the Servitka Roma,Hütz’s songs incorporate elements of traditional Romani music along with punk rock, jazz, ska, and dub. Though his band—a traveling cabaret spectacle—is constantly touring, he has acted in the past, most notably as the grandiloquent Ukrainian translator in the film adaptation of Jonathan Safran Foer’s ‘Everything is Illuminated.’

We were an anti-Soviet family in Ukraine, so we couldn’t give a fuck about anything that was on TV or the radio. I was born to the sounds of Jimi Hendrix and The Doors. My dad was immersed in rock-n-roll, and I picked it up from him. With Mikhail Gorbachev in power, it was obvious to a whole layer of society that this shit could not go on. There was something in the air. I guess a defining trait was the way that initiative, so discouraged in the Soviet Union, began to flourish in 1986 or 1987. There were people who started putting on festivals and events and setting up small businesses—all of which was unthinkable before that. If you had any kind of awakened consciousness, any kind of intellectual insight, you would be expelled from university. This is going to sound hysterical to people today, but in the Soviet Union there was literally no niche for a rock singer or poet—it didn’t exist. If you considered yourself a poet, you were antisocial, a bum. They would give you jobs like working in a boiler room or sewing. Most Russian rock stars worked as janitors. One of the greatest, Viktor Tsoi, from the band Kino, worked in a boiler room. I was prepared to do something funky like that to get by, so long as I could stay on track with my passions.

My family got out of Ukraine in 1989, and we were living in a refugee camp in Austria when the Wall came down, so there was a sense of, If the Wall has fallen, then what was this all for? It took quite an effort to leave, and just as we had overcome this obstacle, the whole thing was up for grabs. But overall, we were psyched. The symbolic power of the Berlin Wall, the rigidity of it as a symbol, was really a major pain in the dick, and when it came down, it gave us a kind of clean slate, so that if it didn’t work out, we knew we could go back. And a lot of people did.

After Austria, I was in Italy for almost a year, getting into the swing of things. I was just hustling, making cash washing cars on intersections, working construction, whatever. I could walk into a store and buy a Sonic Youth record, and I realized that life doesn’t have to be such a hassle as it was in Ukraine. Like, getting a fucking stereo is a fucking life’s effort. To get a record, I would have to skip school and take a train out of town and into the woods, where, like, 200 people were carrying all sorts of Western products. It would take days and all your money—money that you’d saved for three months—to get one record. Like, why was a joyous life so forbidden in the Soviet Union? Suddenly I was able to go to a rock show for five bucks, and the club was downtown—not in some shit place like an abandoned school on the outskirts of fucking nowhere where everything sounds like shit.

Liz Johnson Artur: The Traffic Stopped, and the Poles Took All the Cigarettes.

Since the early 1990s, photographer Liz Johnson Artur has devoted her practice to showcasing the breadth and beauty of black life around the globe—from underground nightlife to intimate familial scenes. The artist was born in Bulgaria to a Russian mother and Ghanian father, and the family moved to Germany when Artur was a child. She recalls driving through Berlin on the day the border opened between East and West Germany.

I used to play competitive handball all around Germany, and on the day when the border opened, we had a game. At that time, we lived in Bavaria, and in order to get to Berlin, you had to drive through the German Democratic Republic. It wasn’t a busy highway, because in the GDR it wasn’t like everyone had a car. There were certain places where you were allowed to stop, and you could bump into East Germans, but you weren’t officially allowed to talk to them. It’s hard to describe, but the rule was that you were only allowed to drive through. Sometimes there were police at the rest stops, and an East German could get into trouble for just for talking to you.

But that day, I was on a bus going to Berlin, and the motorway was full of these cars called Trabant. It seemed like everyone who had a car in the GDR was trying to get to West Berlin. We were stuck on the motorway for three or four hours, and people were just going crazy. It was frantic…and euphoric! People were beeping their horns; some had flags. We had a Western [license] plate, so people were trying to get in touch with us. They said, ‘You know what? There is no border anymore! You can just go!’ And everyone just went. And we happened to be in the middle of it. By accident! No one knew that this would happen. They just announced it. There had been a lot of demonstrations, but to actually open the border was something that no one expected. People were suddenly allowed to come or go wherever they wanted to. It was quite crazy.

The closer we got to Berlin, the madder it was. But we couldn’t just turn around because we had this game. (This was before cell phones.) By the time we reached Berlin, all the entry points from the East to the West were full of people going crazy, so they canceled the game, and we just walked around. The weirdest thing was that the border was open, but the same guards were at the border. You still had some kind of checkpoint. But instead of being really horrible to you, they were really nice.

I had friends who lived right next to the Wall. People with hammers were trying to get pieces of it that they would sell at the flea market. I saw an American tourist who bought a piece of the Wall for 300 D-marks! And it wasn’t just East Germans who could come. Polish people could come as well. There was a Polish market that my friends used to go to because that’s where you could get cheap champagne. The Polish are clever folk. I like them. They used to have these cigarette machines in Germany where you had to put in D-marks. But they figured out that their złotys, which were far less valuable, worked as well, so they emptied all the cigarette machines. You couldn’t get any cigarettes in Berlin in the machine because the Polish got them all!

Harry Nuriev: The Everlasting Effect of Snickers

Harry Nuriev is the founder and architect behind Crosby Studios, a design firm informed by Scandanavian, Japanese, and ’80s deco sensibilities. His work, which spans custom furniture design and interiors, has earned him coveted collaborations with Nike and Rem Koolhaas’s OMA and showings at Art Basel. The Russian-born artist remembers how a simple trip to the grocery store after the fall of the Berlin Wall informed his entire artistic philosophy.

I was born in Stavropol in 1984, during the Soviet period which I remember so well. I remember the country pre– and post-Soviet. When I was a young boy, my grandmother would ask me to go to the local grocery to refill our milk bottle. This experience, which I had time and time again, is something I will never forget.

The grocery had the same produce everywhere. The same milk, the same bottles—everything was the same. Then one day, all of a sudden, I go to the grocery and I see products I have never seen before. Can you picture living in a world where everything around you is the same—then suddenly it changes and you are exposed to a whole new life? Imagine: Do you remember your first Snickers? This has had an everlasting effect on me, and it has played a key role in my design as I use a lot of my heritage and past experiences in my work. It was my first shocking feeling which I try and translate into my work—the same feeling of giving someone a whole new life.

It’s interesting when you live in the same country, in the same city, on the same block, and in the same apartment your entire life, and all of a sudden everything completely changes around you. I best describe this to people as the feeling of moving countries without even realizing you moved or physically went anywhere.

Peaches: Naked People Doing Whatever They Want

It’s been 20 years since Peaches moved to Berlin, where she worked on her debut album, ‘The Teaches of Peaches,’ lighting the fuse for a new era of sex-positive pop that owed much of its kink to the city’s famously transgressive nightlife.

I was there at a very transitional time, but it was also a bit of an empty time. I remember walking in Prenzlauer Berg and hearing music. There was a window open, and I looked in, and there were people playing records, so I jumped through the window and joined the party, and ended up DJing, too. It was just that feeling of, Oh, hey, I’m part of the party now. But there were never a lot of people in all these places. It was just, like, weird little pockets of people. Now it’s the mecca for artists and musicians and dancers, but they don’t make money there. It’s a good central point to work in other places and come back. And you can still go to clubs like Berghain, stay for, like, four days—just walk in, see naked people doing whatever they want, and it’s not a big deal.

Coming from North America, I was interested in convenience, which was never really an option. You’d ask for a coffee to go, and they’d be like, Why? You can just sit here and drink a coffee? I don’t understand? On the other hand, you could drink a beer 24 hours a day. People always think, Oh, it must have been so great, but it was actually not very diverse. It’s way more diverse now, although Berlin still has to grow in that department. When I was doing what I was doing, in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it was a kind of fusing of this punk, I-don’t-give-a-shit attitude with the electronic music that they were familiar with. And that helped people just go, ‘Fuck it!’

Anne Imhof: Nationalism in Germany Never Went Away.

The artist and choreographer Anne Imhof represented Germany at the 2017 Venice Biennale, transforming the pavilion for her boundary-crossing performance piece, Faust, which thrillingly explored the gap between our imagined and real selves. Imhof was born in 1978 and grew up in the countryside, 20 minutes from the border of West Germany and the German Democratic Republic. Here she recalls the night the Berlin Wall came down—and laments the tarnished promise of German unification.

I grew up in a small town in the middle of Germany, quite a sheltered environment. My parents had been born right after the war, and when the Wall came down, I remember the emotional impact it had on my parents. Although I lived in the countryside, the line of the Iron Curtain separating East and West was 20 minutes from our house, where we went hiking in the swamp that we called the Dark Moor. My dad headed there the night the Wall came down, came back muddy, and cried for hours. I saw in him a kind of spark of belief and hope that we could make things better with peaceful resistance which the fall of the Wall signified As a kid, that left a deep impression.

Looking back, it’s hard to separate the fall of the Wall and the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, which happened three years earlier. I was a very fearless child, confident that nothing could happen to me—a very dreamlike state of fearlessness. But when the reactor exploded, my parents began to warn me not to go outside, which was all I had ever done—hanging out in the woods. So this moment of being threatened by something I could not see, and could not grasp, paralyzed me. And at that moment, I think I switched: I became angry and scared, and a little bit of an activist. For example, I would refuse to go on holidays because of the impact of travel on the environment. It was a the desperate attempt of a kid in the nothingness of the German countryside who wanted to do something.

I remember, vividly, visiting Berlin for the first time on my own when I was about 15 or 16. I was befriended by a group of people that I got to know through an older friend. They all came from a town in East Germany and had moved to Berlin in the ’90s when there was a sense of possibility. They were so beautiful to me. Punks in tight leather trousers that they wore every day, all playing music, and walking through Prenzlauer Berg, screaming after their dogs. They represented everything I dreamed of. They taught me how to play guitar. It was a wonderland, basically. I returned home after a few weeks, but it had been the first time I’d experience a community of people from the East—already talking, nostalgically, about the strong bond they’d had there, living together.

For a lot of people, the East and West being united represented a chance, but there were problems also, particularly in relation to how capitalism and fascism came to manifest themselves. The separation is still there, but it found a new form that is harder to track than a wall. Germany now is in a major crisis because of the rise of the far right. Particularly in the former East, they have been elected to positions that have influence over the lives of people. That’s where it becomes very dangerous. Nationalism in Germany never went away; it was always there. Looking back to the period after the Wall fell feels like a dream now. What happened to the promises of unification? People are right to be angry.

Edwina Sandys: From Communism to Capitalism to Missouri: A Berlin Wall Slab’s Journey

The art of Edwina Sandys—the granddaughter of Winston Churchill—includes painting, sculpture, and public works. Two of her large-scale projects incorporate pieces from the Berlin Wall. In Breakthrough, housed in Fulton, Missouri (where Churchill made his famous “Iron Curtain” speech), visitors can walk through a cutout figure of a man. Here, Sandys recounts how she obtained the pieces of the Wall soon after the events that brought it down.

I immediately wanted to get a bit of the Wall and make a sculpture out of it. We [Sandys and her late husband Richard Kaplan] decided to go to Berlin. I didn’t know what I could make because I didn’t know what I would get. I didn’t know if I’d get a piece that was two feet or six feet, or what. When we got there, I realized we might be able to get the full-size pieces because the East German government was selling them. Although the Wall was down, the communist government of East Germany continued to function. Chaos is sometimes worse than anything.

They took us to a yard where we found about 400 slabs of the Wall. They’d sort of dismantled some of them that they thought were more attractive and put them in front. Pretty quickly the East had become capitalistic. They were selling them for $100,000 each, and some people had bought them.

We chose the pieces. Then they said, ‘If you’re not going to pay for it, you have to speak to the Minister of Culture.’ We went to see the Minister of Culture, and I said to him, ‘You know, we would really like to have this as a gift from you to Fulton, Missouri,’ and I started to explain to him this was where my grandfather, Winston Churchill, made the “Iron Curtain” speech…

The man said, ‘Yes, we know all about that.’

I thought that was surprising, and then not surprising, because we always know what the enemy is thinking.

Anyway, he was very nice. He said that before the Berlin Wall came down, ‘I could just tell you yes or no depending on what I thought. But now we’re in a different situation. And you will have to give me a rationale as to why I should give them to you. If you go next door with my secretary, who speaks English, you can dictate something to her and she will translate it.’

So, we went next door and worked with her. And I thought it was amazing: We were all just humans together. We explained why it would be great to have it and where it should be. Then we gave it to him, and he said he’d let us know. And about two or three weeks later, I got a very nice letter in a blue envelope saying that they would be happy to donate to us for the purpose of the sculpture. That was really exciting.

Mikhail Iossel: Drinking, Smoking, and Translating the Mormon Bible While it all Fell Apart

Writer Mikhail Iossel emigrated from the then Soviet Union to the United States in 1986 and began writing in English two years later. When the Berlin Wall fell, he was living in San Francisco, on a prestigious writing fellowship at Stanford.

By 1989 enough events had taken place in the Soviet Union that the Berlin Wall falling was not completely like a thunderbolt out of the blue sky. It was another event. But of course it was symbolic, because walls generally serve two purposes: keeping people out or keeping people in, or a combination of the two. In the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries, walls mainly served the purpose of keeping people in. The Berlin Wall was the ultimate symbol of imprisonment. It functioned basically like a gulag camp because if you tried to escape the gulag, you’d be shot. And if you tried to escape through the Berlin Wall, or over the Berlin Wall, or under the Berlin Wall, you’d be shot.

By then it was already very clear the Soviet Union was falling apart. Also, it happened shortly after the San Francisco earthquake, and I remember basically just spending two days with no lights. The tectonic plates of the world were shifting very far in the life of my former country and beyond and being replicated to an infinitesimally small degree in my own life.

The sense was of turbulence: The world was unimaginable at that point. I had no idea what my life would look like after Stanford. I couldn’t imagine the future of the Soviet Union. I mean, what would happen? It was as though the Wall was the main support of this whole construct of Soviet empire. When it fell down, there was open space with a lot of light. And our eyes were not adjusted to that light. And we didn’t know what to do with it.

Millions and millions of people in the Soviet Union—and also to a lesser degree in East Germany—felt uncomfortable about the fall of the Berlin Wall and certainly about the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Because when you are living behind the Wall, you are protected somehow, and the people who are keeping you within those walls have some kind of obligation to feed you, at least. Like in prison. But when walls fall down, you are on your own.

But also shortly before that time, Gorbachev visited the United States. I was working at a bookstore in Palo Alto. I remember the wild excitement of my coworkers, of everybody. There was a sense of happy uncertainty: There was a new chapter opening up, and we would be witnessing it. In the Soviet Union, it suddenly became much more possible to publish books, from Nabokov on down, all kinds of writers that were previously unpublished. Suddenly there was freedom of speech, more or less. Suddenly full bunches of religious denominations just rushed into the country. Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, anyone you imagined. A huge market, completely not covered, completely godless. Imagine!

By the way, my first income in the United States, beyond working in bookstores, was when my recently arrived friend from the Soviet Union and I were commissioned to translate the Mormon bible into Russian. A splinter group of Mormons out of Kansas City wanted to have their own, because they wanted to disseminate those bibles in Russian in the Soviet Union. And they had heard about this Russian who is trying to write in English. That was me. So, they called me several times, but I wasn’t interested.They said, ‘We cannot pay much, but we will give you $20,000.’ And me: ‘$20,000? $20,000!’ At that point, it is like asking how does $500,000 sound to you? ‘It sounds good! All right, I’ll translate it! What else do you want me to translate?’ This friend of mine and I basically split it down the middle. We were drinking and smoking and translating the Mormon bible.

Sven Marquardt: I Didn’t Leave my Apartment Without Wearing Eyeliner.

For the last 15 years, Sven Marquardt has served as the notoriously fierce gatekeeper at world’s most famous nightclub. Known euphemistically as the Berghain bouncer, Marquardt is the ultimate decider of who is in, and who is out. Here, he remembers his first career as a freelance photographer for East Berlin fashion magazine Sibylle.

I heard Sibylle referred to as the ‘Vogue of East Germany’ for the first time a few years ago. But for us in the ’80s, it was always just Sibylle.

Vogue was only available privately, passed around by friends or family who dared to bring it back across the border. It was forbidden to have Western magazines in East Germany. But there was always something a bit subversive about Sibylle’s editorial voice. The editors always wanted to position the magazine as a little bit international, or as international as was possible at the time.

As a photographer, I didn’t spend much time in Sibylle’s editorial offices. This was partly because they usually featured other German photographers, such as Arno Fischer, Sibylle Bergemann, and Ute & Werner Mahler. The generation before and after us co-founded the agency OSTKREUZ, which shaped the magazine. Also, the fashion editors seemed a bit unsure of themselves.

It was the ’80s. The zeitgeist of punk and new wave shaped a whole youth culture around the world, including East Berlin. This culture of protest manifested itself in our style too: Mohawks and shredded leather. Back then, I didn’t leave my apartment without wearing eyeliner. We lived and thought differently, so we wanted to look different, too. Of course, this youth culture was met with no great affection from the state, so they enacted new laws and prohibitions. They wanted us to make us disappear.

At the beginning of the ’80s, my passion for taking pictures was sparked. Working for Sibylle now and then made me a bit proud. So, I went to the editorial office when the editor-in-chief was not there and picked up a job. Just recently, I thought, Who knows…we might have got along quite well. Only our personal styles were a bit different.

Translated from German by Michael Haggerty

Thierry Noir: On the Red Rabbits of Potsdamer Platz

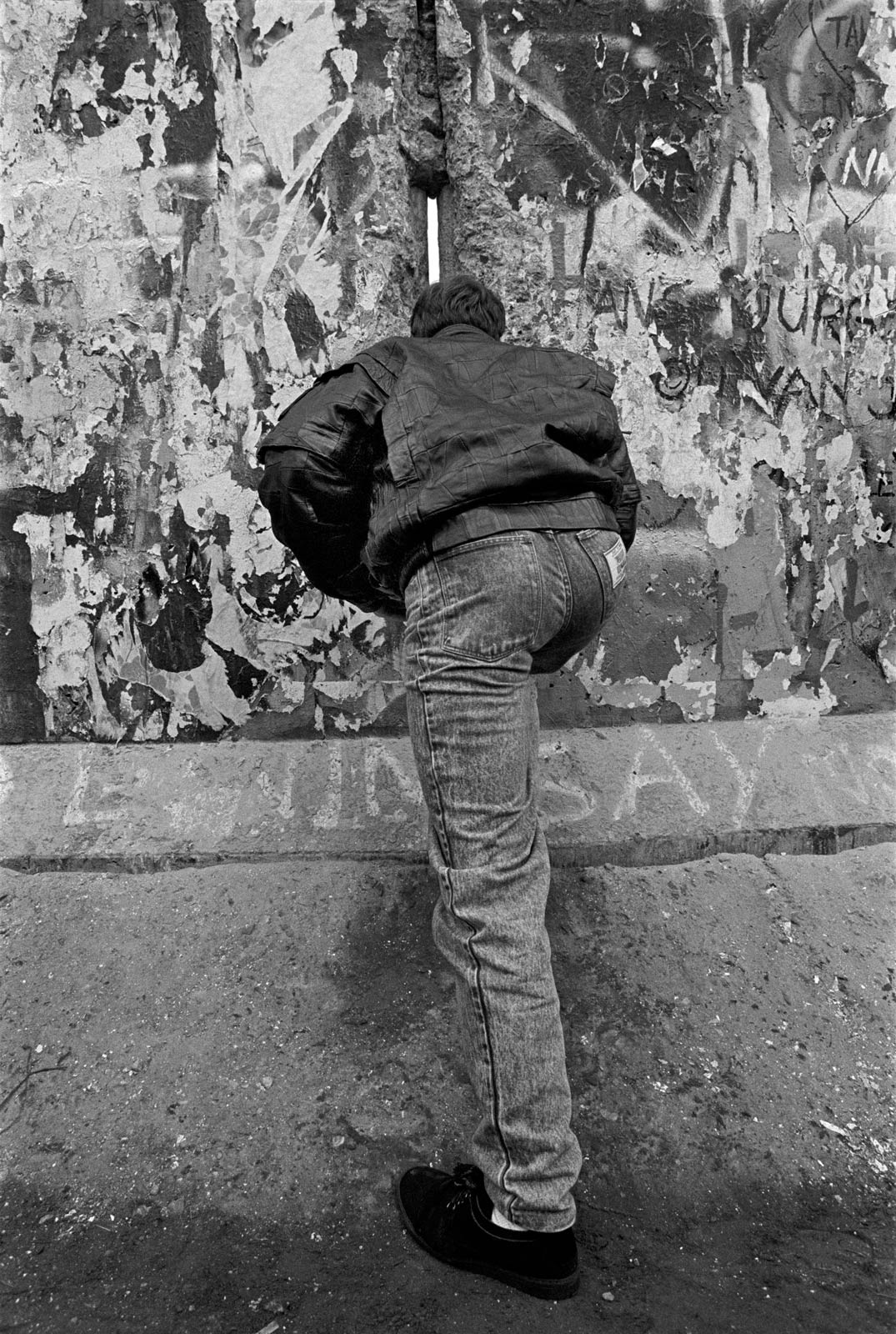

Artist Thierry Noir moved from France to Berlin in 1982, inspired by influences like David Bowie and Nina Hagen. Two years after arriving, while living at a guest house that backed up to the Wall, he began painting it, collaborating with artist Christophe Bouchet to salvage paints and materials left over from a German beautification project. By the time they began painting, many people had already died crossing the Wall. It was necessary to work quickly to avoid GDR guards, leading to a technique that Noir developed into his “Fast Form Manifest.”

Two weeks [after the Wall came down] I was invited by the French consul in Berlin, because a man from Paris had the idea to bring 1,000 kilos of colors to paint, for the first time, the east side of the Wall in Potsdamer Platz, in the center on the Berlin. I went through Checkpoint Charlie with my car for the first time. I had never seen the other side on my own—only from television and from my window— because I was living very close to the Wall. Suddenly, I saw the misery the Wall was hiding. It was all gray—abandoned construction areas, started and not finished. Even the trees were green-gray. The cars. Those boring cars they had were also amazing: The Trabants were stinky. The pollution was really immediately different than in West Berlin.

And then I arrived right on Potsdamer Platz. All the colors were there in front of the Wall, and the East German artists were dressed like old-school artists. It was so funny to see them like that. They were smoking and thinking, and then some television team was there, waiting. Nothing happened. Then suddenly, I started to paint as I didn’t want to wait, and the one East guy told me, ‘Hey, this is my place!’

‘What is your place?’

‘Yes, I reserve that place to paint.’

I said, ‘Oh no.’ That was so bizarre me. One quick afternoon for the television, and we finished.

The next day the guards painted everything back in white. They were not amused to see painting on their Wall because Potsdamer Platz was a special part of Berlin. It was a huge no-man’s-land, and because on Potsdamer Platz three sectors were there together—the American, British, and Soviet sectors. So, there was a huge abandoned area at Potsdamer Platz with no trees—no nature. A huge abandoned empty [area] made of sand and watchtowers. And lots and lots of rabbits were jumping around. They were the same color, like sand, so it was impossible to see them except when they were moving. It was very bizarre. So, on the west side of this area of the Wall, I painted a mural for them. It was called Red Dope on Rabbits, because the soldiers there were spreading a kind of red liquid all around that area trying to kill all the nature on the ground. It was a remake of “White Punks on Dope.” You know that song? So I made Red Dope on Rabbits. Like I said, those paintings on the Wall in the middle of the city of Berlin—it was kind of a mutation of the culture because it was not normal to have hundreds and hundreds of meters of painting in the middle of a big city like Berlin. And at the same time, it was not normal to see red rabbits jumping around in an empty area in the middle of a big city. It was like a mutation of nature. Then those two mutations were very visible on Potsdamer Platz. That’s why it was a special point in the city.

They are still there, those rabbits! Not like before, but in certain points of Berlin you can see them in parks. They are still there. They survive everything. Those rabbits.