The photographer has dedicated his career to pulling back the curtain, but in his new book 'Amen Break,' he creates magic by scrambling the familiar

Thomas Prior is an extraordinary photographer whose images are defined by what photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called the decisive moment, “the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.” Prior’s career has been marked by laboring to capture the perfect photograph: ethereal in its subject matter, flawless in technical execution, seemingly effortless when produced in finality, and rendered in impossibly beautiful technicolor tones. In one image, children swimming in the sandy washes of a paradisal beach are joined by a passing airliner jet’s humongous shadow; in another, gymnast Simone Biles exudes kinetic grace even while frozen in mid-air; in yet another, a somnolent vacationer’s midriff-hanging swim ring looks like the absolute accoutrement of touristy death. In my favorite of his images, produced for Monocle, Prior documents game show productions, perambulating from set to set photographing their ins and outs like little terrariums, focusing on small details such as cameramen, hosts, contestants, and audience members in an act of meta-documentary, showing us staged life as it unfolds by pulling back the curtain.

“I have to constantly stay vigilant,” Prior tells me. “I tend to turn up all the antennas every time I have a camera on me—to the detriment of almost everything else in my life. You know, it all just kind of falls away,” he chuckles mordantly.

It’s difficult to comprehend Prior’s gift for the decisive moment—equal parts preternatural and practiced. As a recovering photographer, I have labored on but a few occasions to try to reproduce photographs with the magic of the decisive moment; that is to say, while it is difficult to comprehend his photographs’ creation, it is even more difficult to emulate the technical mastery. “[I] have a little OCD issue and it’s a lot to do with that,” Prior says of his approach to editing. “I kind of enjoy the process. But it’s a painful enjoyment of, like, when is this done?”. In one photograph, Prior snaps a pyrotechnic, nighttime explosion in a crowded Mexican street, perfectly composed and suspended in time for all of us regular people to see. It is excruciating to put into words just how difficult it is to capture such a fleeting moment.

In my viewing of Prior’s work, the words of other photographers come to mind. The late Bill Cunningham, for one: “It’s true today as it ever was; he who seeks beauty will always find it.” Annie Leibovitz warns photographers—and I’m paraphrasing here—that when capturing subjects in motion, if you’ve seen it through the viewfinder, it’s already too late. Meaning: you have to have an instinct for making the photographic image before the photographed event has even occurred. And this is Prior’s gift, an almost purely instinctive awareness. “I am attracted, naturally, to action and fleeting moments, like most people.”

Prior’s latest offering is a book that documents 2020, precarious history as it unfolds in front of us. Amen Break (available now via Loose Joints) is named after a singular drum beat that has been heavily sampled in the history of hip-hop music and has come to define drum and bass and jungle music. Comprising 76 pages and 47 color images, the book is Prior’s second (when I ask Prior if he enjoys the bookmaking process, he tells me, “Not especially…the first one was torture.”) and is a photographic journey of New York City amid COVID-induced lockdown and in the context of the George Floyd protests, which erupted across the city throughout the summer of 2020.

The photographs in Amen Break are peak Prior in style and indicia—rich reds, and blue hues which at their highlights are almost green, with Prior’s humorous perspective always throughout. (In one photograph a telephoto lens allows viewers to spy on two city pigeons, who are, apparently, mid-coitus.) Whereas Prior’s commercial and editorial work often involves conditioning the settings around him such that the decisive moment, lost to the sands of time, can be captured, Amen offers a glimpse into what might be an inverted process for Prior: the solemn observance of the found moment amid settings conditioned by our uncertain political present.

While the photography we’ve come to associate with Prior is often centered on discovery—piercing through the veneer of Washington intelligentsia or the cockpit door of a NASA jet, or simply a photographic frame that acts as window into a far-off city illuminating a far off night sky—the photographs in Amen are a contemplation of the present: the immediacy of New York City, where the 41-year-old has lived for more than two decades, and the urgency of the unique present marked by pandemic and protest. In this book, we see a photographer’s evolution: instead of making clear the foreign, Amen is a scrambled vision that puzzles the familiar.

In these photographs, feelings of confusion, claustrophobia, and uncertainty about the future are reinforced by the formal elements. The crops are tight—zooming in on the charred blue and white detail paint of a police car, or a long trickle of crimson blood on the otherwise pristine door handle of a white sedan. There are no vanishing points, and what we are shown is often a vision of halting obstruction: in one photograph, a curtain blocks our view of morgue attendants and autopsticians as they do what they do. In another, four makeshift morgue trucks wait to carry away COVID fatalities against a backdrop of New York City buildings, the composition giving the impression of massive structures stacked on top of each other, with nowhere for the viewer’s eye to rest or find refuge in the crowded frame.

After the murder of George Floyd, Prior, like so many New Yorkers, became more attuned to the inequalities around him. And as the protests migrated to New York City, Prior began to see the problematics in the proximal. To walk through SoHo was to experience a giant shopping mall full of antagonisms, and the West Village’s Bleecker Street, lined with upscale boutiques, suddenly felt like a parody of consumerism amid pandemic.

“Now, when you see an empty storefront, it’s like, ‘That’s 30,000 dollars a month? That 400 square feet costs 30,000 dollars a month?’” he says. “Then you’ve got these morgue trucks and people living in overcrowded NYCHA housing towers that have become one big infection site because the city has totally neglected them.”

“[I] took a walk down to SoHo the next day and there was plywood on the Louis Vuitton store and then in the West Village on Bleecker there was all this paper in the storefront windows. Immediately, I thought the paper was interesting. This idea that there were these things for us to look in and want and desire, and now they were being covered by the same brand of paper and in different ways. The windows and mannequins throughout the book became a mirror to the phase of the shutdowns and lockdowns and protests and everything else.”

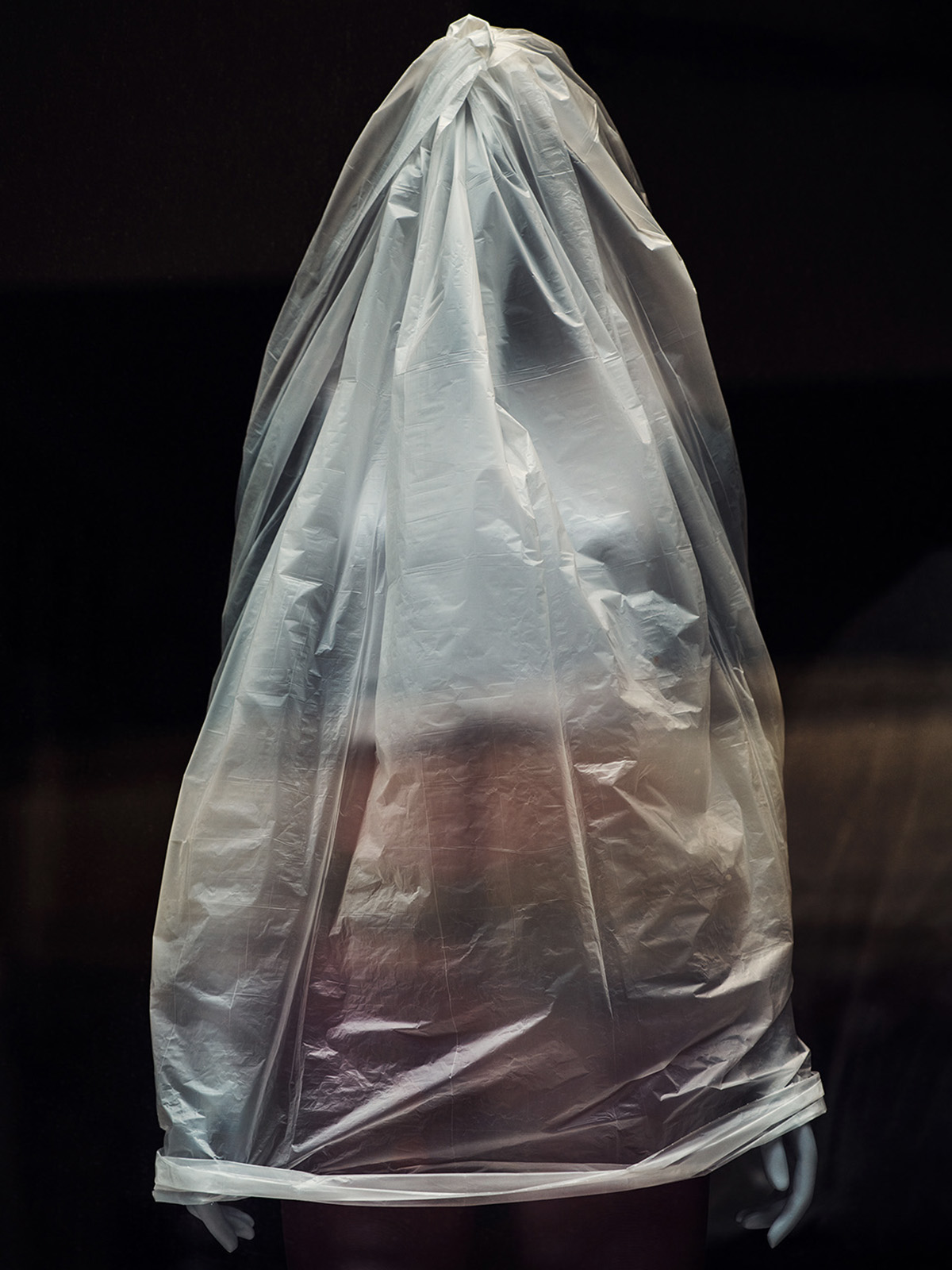

Many of the photographs in Amen are visuals of obstruction. A mannequin covered in plastic behind retail glass conjures eerie visions of a dead body lying cold in a morgue, and a set of brown shopping bags is pressed against a storefront windowpane as if to escape.

If Prior’s photography gives viewers a glimpse into unknown lands, in Amen, a photographic antithesis emerges: by emphasizing the direct obstructions of the ‘new normal,’ Prior’s deliberate photographic inquiries are not marked by joyous excursion or peeking behind the curtain. Instead, his tight and decidedly flat frames capture broken glass, plywood, trapped mannequins and papered over storefronts (once meant to be inviting), shrouds the documenter cannot pierce through. The viewer is left wondering: what lays in store behind the curtain? What is the thing we are not supposed to see?

Amen Break by Thomas Prior is published by Loose Joints and is now available for purchase here. Proceeds raised from the book will be donated to 9 Million Reasons, NYC’s largest and farthest-reaching community food pantry that provides free food for anyone in need. Additionally, donations from Loose Joints will be 200% matched by a private sponsor.