Document celebrates World Watercolor Month with Tschabalala Self, Mats Gustafson, and more.

Watercolor painting is one of humanity’s oldest mediums, stretching back past ancient times to prehistory, when early humans used the technique to decorate the interior of caves. In the spirit of World Watercolor Month—yes, it’s a real thing—Document takes a look back at the work of five of our favorite artists to highlight how their contemporary use of watercolor captures the fluidity of human form and identity.

Mats Gustafson

Renowned Swedish fashion illustrator Mats Gustafson adopted watercolor as his primary medium in the late 1980s, when he started collaborating with Italian designer Romeo Gigli. “Things were changing at that time; he changed the rather aggressive ’80s [look] into something much more romantic and poetic,” Gustafson explains in a 2017 interview with Vogue. “I started to do more and more watercolors [that] suited that time and that softer, more sensual style.”

Today, he is credited as an artistic trailblazer, both for reinvigorating fashion illustration when photography was eclipsing the genre and for choosing to use watercolor to do so. When asked about his choice of technique in a 2017 interview with Filep Motwary, Gustafason explains that “technique per se is something I find less interesting, but watercolor is a medium I’m comfortable with: it suits my temperament—I work fast.” Although the quickness and lightness of his illustrations suggest that they took just a few minutes to paint, he emphasizes that “there is a lot of work to get to that point.” Behind each of Gustafason’s finished artworks there lies a stack of earlier versions deemed imperfect; he has to start fresh every time he thinks he can improve on a piece because little can be changed once the water dries. “To me, the beauty with watercolor is that you need to allow yourself this element of chance.”

Alice Neel

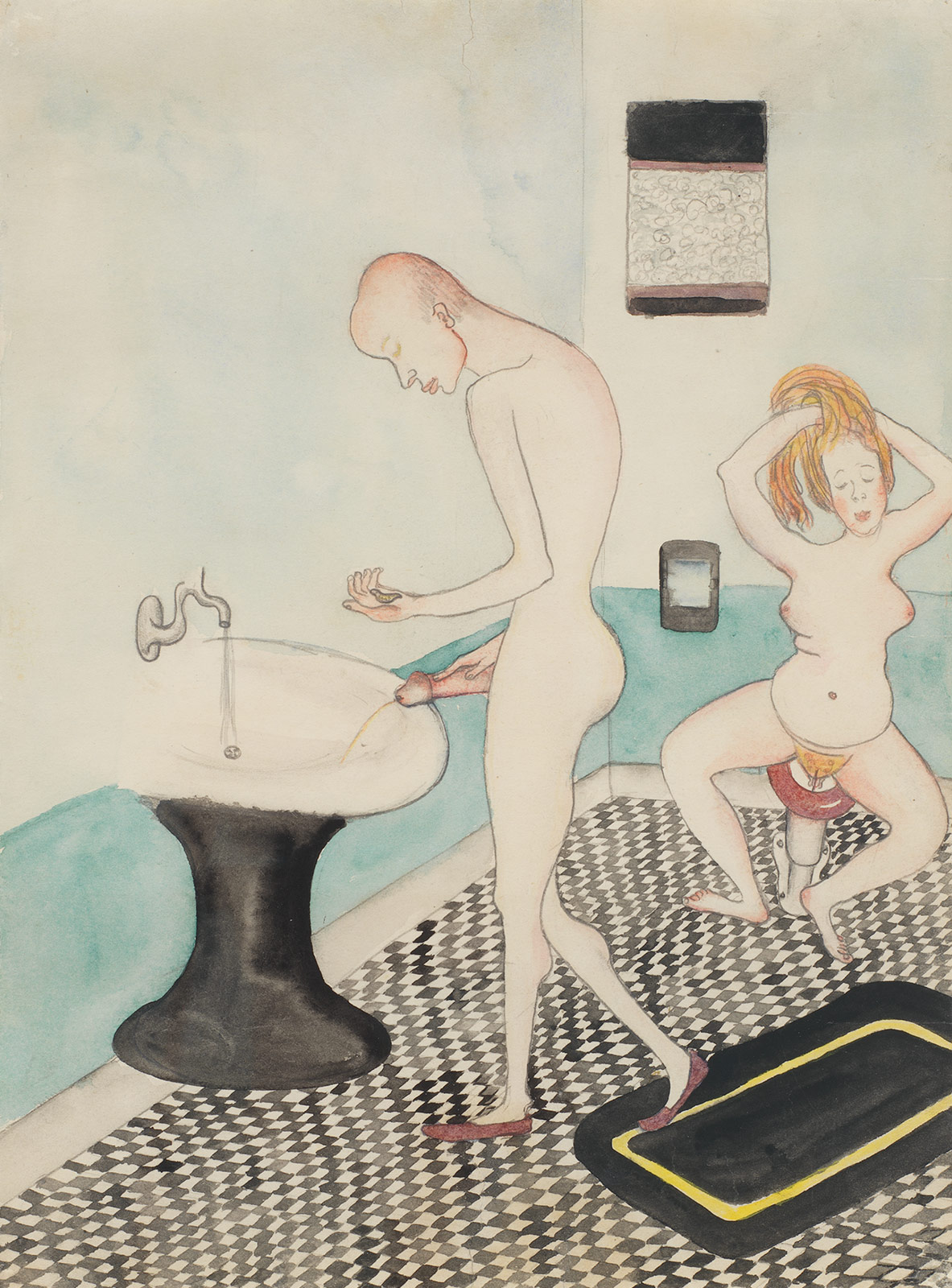

Born and raised in a traditional middle-class Pennsylvanian household at the turn of the last century, Alice Neel broke every mold. By the time she passed away in her NYC apartment in 1984, she had become one of the 20th century’s greatest American painters, most famous for her representation of the human form. “Whether I’m painting or not, I have this overweening interest in humanity,” she once said. “Even if I’m not working, I’m still analyzing people.” Pamela Allara, author of an award-winning book on Neel’s life and work, describes the painter as “a sort of artist–sociologist who revived and redirected the dying genre of ameliorative portraiture by merging objectivity with subjectivity, realism with expressionism.” In Untitled, the bathroom scene pictured, we see the contradiction of Neel’s style play out in the interaction between two mediums—watercolor and pencil. The softness of the peach skin is bordered by solid graphite lines; the bodies are a fluid contained. This duality speaks not only to human nature, but also to Neel’s own definition of art: “a search for a road and a search for freedom.”

Aurore de la Morinerie

After graduating from the fashion section of the Duperré School of Applied Arts in Paris, Aurore de la Morinerie started her career as a fashion illustrator in the 1990s. She draws artistic inspiration from her travels, with a particular passion for the aesthetics of Japan, China, and India. In fact, Morinerie studied Chinese calligraphy for two years, which has become an important influence on her work. Unlike Alice Neel, Morinerie offers watercolor renditions of the human form with no frontier between body and page.

In the piece pictured, from her illustrations of the first Artisan collection for Maison Margiela by John Galliano, the paint of the model’s bare legs is so faint that it’s hard to tell where her body ends and the blank page begins. The model fades into the background, and in turn, the sensational couture outfit she’s wearing is foregrounded. Although Morinerie doesn’t paint a background, she nonetheless creates depth and movement on the page through her use of watercolor. Like chiffon on the runway, the transparency of the paint lets the light of the white page beneath it shine through.

Tschabalala Self

Unlike the artists highlighted above, Tschabalala Self doesn’t work with watercolor as a primary medium, but rather incorporates watercolor into her multimedia “paintings”—along with acrylic, flashe, colored pencil, crayon, hand-colored photocopy, hand-colored canvas, faux jewels, and more. “I call the works painting because they’re using a painting language,” the Harlem native explains in a 2017 interview with the Creative Independent. “I think my understanding of a painting is one of color relationships or the relationship between different objects on a pictorial plane. … The point of the project is to create new narratives.” While the other four artists’ use of watercolor captures various dimensions of the fluidity of human form and identity, Self approaches the artistic representation of black women’s bodies by establishing a subversive technique of her own. In a 2018 interview with Bomb Magazine, she elaborates: “One individual having many parts. One individual being made from lots of different distinct elements. So the way the work is actually made forms how it is meant to be understood.”

Eri Wakiyama

Illustrator Eri Wakiyama was raised in Northern California by Japanese parents. Ten years after graduating from Parsons School of Design with a degree in fashion design, she was commissioned by Miuccia Prada to draw several prints for Miu Miu’s Spring 2015 collection, which were shown at Paris Fashion Week that year. Although Prada got her some media attention, Wakiyama is still better known for the illustrations she posts on Tumblr and Instagram of her unnamed recurring character, above. In a conversation with jewelry designer Yoon for Document last July, Wakiyama describes her: “She is almost androgynous. She is always in a different situation, with a different personality, but it is always the same girl.” The fluidity of these watercolor illustrations and of this character’s identity resonates with how Wakiyama talks about her own identity as an Asian-American woman: “We are a mishmash of things. I don’t feel more powerful in one thing or the other. Everything influences me.” Wakiyama and her art both lean into the fact that identity is inherently unstable—as fluid as light unraveling onto a pool of water or watercolors blending in the capillaries of a sheet of paper.