For Document’s Spring/Summer 2025 issue, Sam Venis examines how the human body is being reshaped in the image of the machines it once controlled

I’m home in Toronto for a visit, and my parents agree to drop me off on the other side of the city. It’s a place they’ve been before many times, a city they’ve driven in for three decades. Instead of using their own mental model, they enter the address into Waze and start following the app through back alleys and awkward turns in the hopes of shaving a few minutes off the clock. They’re stressed out following along, but they do it anyway. Eventually, their turns become slower, they change lanes less—the app shows them how to move. It reminds me of the early Uber days, before live pins, when drivers would cancel the ride if you walked half a block up the street because, beyond the app, they had no external reference for the streetscape. I remember thinking their mindless style of driving seemed like the first stage in a training phase before driverless cars. The humans in this system were just a pass-through implement, a proxy of the machine training the machine.

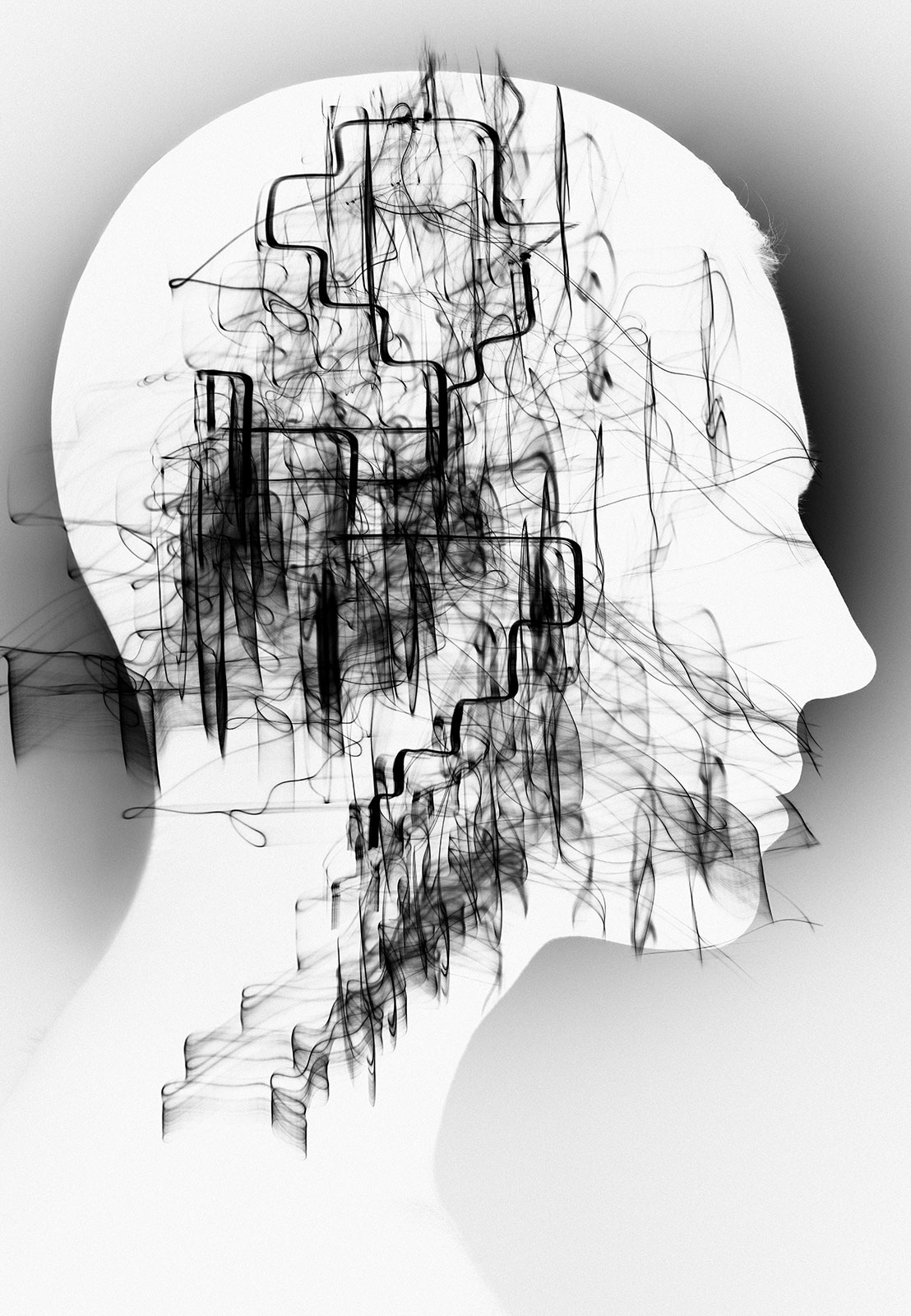

My parents abandoning their own conception in favor of the real-time data-informed route is just one example of a growing phenomenon: Have you noticed that people have started acting more like their computers? It’s not something I can prove to you with statistics. The New York Times hasn’t yet discovered a measurement for the extent of synthetic mimicry. But it’s happening, and I’m sure of it. Maybe you are too. More and more, people are acting like avatars of a mindless, yet somehow conscious, machine.

Another example: Two years ago, a video went viral depicting a streamer named “Pinkydoll” pretending to eat ice cream like a dog. “Mm, ice cream, so good,” she repeats, as she collects coins from her viewers. Her eyes are dead, her skin smooth like a Barbie doll’s. In the wake of the video’s virality, a ream of think pieces emerged explaining that this style of content and performance is a genre called “mindless NPC.” It’s named after the side characters in video games who don’t have consciousness, the idea being to mimic the jerky movements and vague sexuality of a computer simulation. As Joshua Citarella put it on an episode of the New Models podcast, “If you look at TikTok, your body is literally animated by the algorithm—it tells you how to move yourself.” As you follow along, he says, “you end up dancing for this abstract formulation of capital and algorithmic recommendation.

“Johnson has entered a fantasy world with no ambiguity, a self-created metaverse of pure zeros and ones. He’s moved by an algorithm, an authority beyond himself, and he appears happier for it.”

But this synthetic mimicry extends beyond the mere physicality of movement. In a recent Netflix documentary on the biohacker Bryan Johnson, the camera focuses while Johnson stands in front of a special white light mirror in his bathroom. He downs three pills, then swallows a chalky supplement milkshake, turns on his hair growth cap, and gets ready for his exercise regimen, abdomen stimulator, and so on. The regimen is rigorous and involves measuring every form of his biometric data, from heart rate to the duration of his boners when he sleeps. Johnson claims to be aging in reverse by following a “protocol” he developed with an anti-aging doctor. It came together, he explains, when he learned that instead of allowing his own mental desires to guide how he behaves from day to day, he could outsource the question to a higher intelligence: the brain inside his body, sensed, measured, and analyzed in the form of biometric data.

While the film argues that his motivation is the desire to live forever, Johnson’s explanation for his behavior is even more simple: “I’ve developed an algorithm that takes better care of me than I can myself.” In his protocol, a health system he calls “Blueprint,” Johnson has found an objective measure of well-being, a way to condense all of life’s messiness into a single metric of success: the extent to which he can reverse his biological age. Like an influencer refreshing his follower count on Instagram, Johnson tracks how he’s reversed his age by 5.1 years and counting.

The astounding part of watching Johnson is not just that he’s so strange-looking and vampiric, like an Apollonian statue cut by Botticelli, but that, in his total devotion to his own “objective” algorithm, he seems to have transcended the turmoil and indecision that plague human psychology. Johnson seems like a guy who just turned off his brain altogether. When asked why he cherishes friendship, he responds that psychological data suggests companionship is an important ingredient in a long life. Johnson has entered a fantasy world with no ambiguity, a self-created metaverse of pure zeros and ones. He’s moved by an algorithm, an authority beyond himself, and he appears happier for it.

For years, AI theorists have been predicting a future where computer algorithms become better predictors of human happiness than the natural evolutionary algorithms of our own biology. In Homo Deus, for example, Yuval Noah Hariri argues that with enough data collected from your conversations and search histories, computer algorithms will soon become better at predicting the success of our most intimate decisions, like our choice of a partner or career, than the biological algorithms we call feeling. One way to view Johnson, and the lifestyle he’s designed, is that he’s the first person to take this notion completely seriously. Just as Jesus was the spirit of God made incarnate—the god of the Hebrews, descended in a man of flesh—Bryan Johnson is the desire of The Cloud made incarnate—the god of the tech bros, with its first avatar in the life of man.

Humans have always mimicked their machines. From the spiritual connection between Mongolian hunters and their bows and arrows to the drummer who becomes inseparable from his kit, humans have always fantasized about the synthesis between their bodies and their tools. And while this bond between man and machine can be absorbing, even healing, this merger is intrinsically tied to systems of control.

This was the observation that drove Michel Foucault to develop the concept of biopolitics in the 1970s. Noticing the ways that humans in the age of large machinery were surveilled and disciplined, Foucault argued that the rise of industrialization, and the focus on statistics that was exemplary of the Enlightenment, gave rise to the concept of “populations,” which have to be managed and enculturated for the sake of progress and growth. To convince

people to alienate themselves from the fruits of their labor, social systems had to discipline bodies into meeting the requirements of their labor. So, good health, in such a system, was defined by a person’s ability to be a productive worker.

But as neoliberalism emerged as a mutation of capitalism, the demands of the body evolved. At a time when “knowledge work” became the driver of economic production, it was important for workers not just to optimize their bodies, but their minds, too. Byung-Chul Han describes this system in the name of his 2014 book, Psychopolitics—the policing of the self by the self. Free markets, open borders, and unlimited growth gave rise to the worker who needs to think of their life as a startup. Instead of a “disciplinary society” defined by “negative power,” where workers are told what not to do, neoliberalism called for an “optimization society,” shaped by “positive power,” where workers are told that their personal growth is the only thing standing in the way of their success. Think: Tony Robbins and the legions of hustlepreneurs. As Han argues, “the auto-exploiting subject carries around its own labor camp; here, it is perpetrator and victim at one and the same time.”

Countless commentators have pointed out, however, that capitalism is beginning to mutate once more. As Greece’s former minister of finance Yanis Varoufakis argues in his 2023 book, Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism, the system of production we now live under is more like the system of rites and privileges that defined the aristocracy during the age of kings. Owners were paid a tax by the renters who worked their land and used their tools. The platforms of today, from Amazon to Meta to X, have become critical infrastructure, Varoufakis says, like the wheat grinders of the past that serfs were forced to use to make their bread. Rites are dished out to the new aristocracy in the form of access to capital, which is virtually synonymous with access to computing power and data.

The defining quality of this system, Varoufakis argues, is converting mass quantities of data into increasingly better systems of prediction and surveillance. It’s similar to the concept of “dataism,” that modern society’s core philosophy is belief in the power of data. As David Brooks framed it in a 2013 New York Times article where he coined the term, the idea is “that everything that can be measured should be measured; that data is a transparent and reliable lens that allows us to filter out emotionalism and ideology; that data will help us do remarkable things—like foretell the future.” Of course, when Brooks introduced the term, many of the nasty side effects of the shift to dataism had not yet become clear. This was the Obama years, the age of the TED Talk. Uber was just then making its appearance alongside platforms like WeWork and Airbnb. Driverless cars were still a distant idea. AI was only functional in the lab.

The examples Brooks selects for his article are telling. He describes how large volumes of data can help us rethink the nature of hot streaks in the NBA, the effectiveness of campaign spending, the subtle verbal cues that signal trustworthiness or deception in conversation. But with a decade of hindsight, we know that alongside these positive uses came a list of dangerous, corrosive externalities and manipulations. Instead of efficient campaign spending, we got armies of bots conducting information warfare. Instead of drone delivery apps, we got drones to blow people up in refugee camps. Instead of democracy, we got oligarchy and tribalism. Instead of better products built with more rigorous data, we got enshittification—Cory Doctorow’s term for the systematic quality decline you find on platforms once their customers are locked in.

But more than anything, Big Data has meant Big Surveillance. A panopticon on a global scale, beyond Foucault’s wildest dreams. This raises an important question: If it’s true that capitalism has begun to mutate into a new system—if we’re right to view the last 20 years of data collection as the preparatory phase for an automated, AI-driven system to come, and, if we’re right to expect that as the locus of the system changes, the politics of the body will change, too—then what does the new system want from the body? Who is the optimal producer in a system forming humans into cybernetic organisms?

One answer is that in a system defined by dataism, the optimal body is a mindless NPC. As in The Matrix, where human minds are dropped into a widespread, all-encompassing simulation, their bodies plugged into biofuel tanks; if humans stop being relevant to production as AI accelerates, humans might as well become an electric utility.

That could be one way to understand what’s happening with Pinkydoll and Johnson—that in their synthetic mimicry, we’re beginning to see the telos of a system that wants humans to become machines. This view is common among AI “doomers,” who argue the history of software evolution is leading to human replacement: it starts with mass, decentralized data collection, passes through a phase of human-machine augmentation—think: my parents in the car—and eventually leads to replacement or erasure. Uber gives way to Waymo; surgeons become robots; all the books, blog posts, Wikipedia entries, and Reddit forums that formed the history of the internet become ChatGPT. From this perspective, Pinkydoll and Johnson are like emissaries of the future, anticipating the arc of technological history and signaling what’s to come. A world where the foundational elements on which we’ve built civilization for the last 10,000 years are no longer relevant: memory, literacy, feeling, even the premise of a society composed of individuals. That’s the world we’re heading toward, according to Han: dataism is data totalitarianism. So the best we can hope for is civilizational experiments in pan-cultural universal basic income, since, if jobs disappear in a post-scarcity future, we should at least guarantee a minimum payment from the government. To resist, we should go off-grid, buy dumb phones, raise chickens in the garden. Restore our private Eden one act of romanticism at a time.

“But more than anything, Big Data has meant Big Surveillance. A panopticon on a global scale, beyond Foucault’s wildest dreams.”

The other main school of thought is that humans merging with machines is not only inevitable—and already happening, as evidenced by the market for prosthetics, buzzy startups like Elon Musk’s Neuralink, or even just the fact that all of us walk around with a second brain sitting in our pockets. Often with spiritual gusto, proponents argue that such a development will be wonderful for mankind, the dawn of a new era of life on this planet, capable of correcting the nasty, brutish, and short lives of our mere humanoid past. “DNA is basically software,” Mark Hamalainen, an educator in the longevity space recently said to me. “So, eventually, you can just imagine us getting software updates.” Tech people invested in mass cyborgification promise that such transformations will deliver sci-fi marvels such as the eradication of illness, the arrival of eternal life, and Matrix-like brain-processing abilities to accelerate skill learning and information retrieval.

Of course, this is met with skepticism. Why should we trust tech billionaires to go about this kind of research safely or verifiably? Provided they succeed at their moonshot and figure out how to start converting the body into an eternal machine, why wouldn’t the “product” simply become another techy way to hoard power and political control? Given the philosophy of “move fast and break things,” combined with the uncanny degree of influence that the tech oligarchs have accrued in the past decade, why would anyone choose to stick their hands in that proverbial cookie jar? In the most likely scenario, we get an even more exaggerated set of class differences as the elite chooses to live forever and hoard their money for longer and longer. And in the worst, a bifurcation—where different species of humans start roaming around, manically optimizing their body software until, eventually, homo-luddite is wiped out by an overclass of cyborgs.

So who is the optimal producer in that context? One answer could be: a being that retains the capacity to do stuff that humans are uniquely good at—like creativity, abstraction, combining ideas, breaking rules, pursuing chaos—with none of the drawbacks of human bodies—like fatigue, anxiety, the need for large quantities of food, the constant risk of terminal immolation at the hands of a falling piano or a distracted driver checking their phone. Early science fiction writers, and especially the Russian cosmists, fantasized about this intellectual merger, arguing that such a process was not only critical for our survival as a species, but it would also lead to our political emancipation by ushering in an age of plenty, where the eradication of 20th-century ills like disease and food scarcity would provide people with time to work on creative projects.

Of course, as we know, this didn’t happen in Russia or the West. In fact, as David Graeber argued in Bullshit Jobs, the opposite took place. Instead of the economic surplus of increased worker productivity being used to eliminate social inequality and free humans from mundanity, many of us find ourselves clinging to nonsense email jobs, or otherwise stuck in a downward spiral of contract labor with little to no social security. One culprit, no doubt, is neoliberalism, a set of policies which, among other things, modified tax incentives at scale. Because corporate taxes were so high in the 1970s, it made sense for companies to fund scientific research, since, if they didn’t spend it internally, their money would just end up with the government. But as tax rates were lowered, instead of funding more research, as the companies claimed it would, the additional profits were directed to stock options and dividends—which, in effect, was a great way to flash-freeze the status quo. But another has been the Left’s inability to form a coherent response to these forces. In a departure from early socialists who believed that technological acceleration was the key driver of political emancipation—that solving world hunger and ending the world’s energy crises through technological means was central to a workers’ revolution—the Left’s recent response to Silicon Valley has instead tended to focus on a now-familiar brand of intellectual naysaying. What tech theorist Benjamin Bratton calls “negative biopolitics”: rejection of the current trajectory without a vision of what might happen instead.

In fact, this was the basis on which Donna Haraway, in 1986, framed A Cyborg Manifesto—as an intervention in a similar intellectual pattern within feminist discourse. Rejecting her colleagues’ romanticization of “the natural” and their general antipathy to all things technological, she wrote of the cyborg, that “in our present political circumstances, we could hardly hope for more potent myths for resistance and recoupling.” In a world where technologies like hormones and the birth control pill had made it clear that the body’s “natural,” inherited qualities could be transformed and manipulated, it was no longer possible to argue, scientifically, that the “natural” limitations of the body were predefined. This meant that they were open to interpretation—which is to say, within the purview of politics. As Haraway wrote, “the cyborg is not subject to Foucault’s biopolitics; the cyborg simulates politics, a much more potent field of operations.” For Haraway, the soft materialism of the cyborg—its monstrousness and illegitimacy—is what gave the image its power as a catalyst for political change.

This is to say that, perhaps instead of viewing Bryan Johnson’s hunt for immortality—his search for a higher intelligence in his “body’s brain”—as a familiar brand of tech bro grift, we should see, in his obsessive counting and quantification, the emergence of a new apparatus of perception. A perception that plays with the “natural” limitation of the body—the limitation of death—and asks how it might be transcended, how our civilization-wide efforts in biometric tracking via smartwatches and step counters can help us understand disease and heal each other. In Pinkydoll’s performance as an NPC, instead of fixating on the mindlessness, its passivity, we can see the emergence of a new form of dance, no different from the robot, the locomotion, voguing, or the boogaloo—each part of a lineage of popular dance moves inspired by technology and industry. As the writer Robert Bolton noted in an essay on NPCs, “each dance both literalizes and subverts its own technocultural fantasy: to be powerful and efficient, to be glamorous and immortal, to be frivolous and fantastical, to do the impossible, to be liberated of earthly constraints.”

Byung-Chul Han alludes to the range of possibilities inherent in our current societal transformation when he argues that the arrival of dataism has been tantamount to a “second enlightenment.” His point is that Voltaire and Rousseau were also obsessed with statistics—an element of 18th-century rationalism arguably more constitutive of the Enlightenment than anything else. After all, you need a pretty good system of calculation if you’re going to manage colonial populations and still operate a state. To plan a Napoleonic War, you need a Rothschild. To enlighten the masses, you need a printing press.

This means our own “second Enlightenment” comes with all the baggage of our colonial histories, eugenic experiments, genocidal wars, and exercises in population control. But it also means that, in the process of reshaping the metaphysics of the human, we can open ourselves to the possibility of writing a “positive biopolitics,” an affirmative vision of our technological future, that sees the individual self as part of an entanglement with others, an immunological vision of society that sees our social systems as part of a single organism learning to act together. Already, our networks of commerce, power, and communications are as richly interconnected as plant ecologies and nervous systems—a fact that’s equally as dangerous as it is emancipatory. So the question we should be asking is not, how do we stop innovation in its tracks or prevent the body from changing, but rather what is the Left’s positive vision for technological biopolitics? Maybe the arrival of the cyborg doesn’t signal the death of ancient wisdom and self-understanding, but the ground for a new kind of wisdom to be envisioned, designed, and born.