The ChatGPT-powered characters go to work, flirt, and throw Valentine’s day parties—forecasting new uses for AI in the study of human behavior

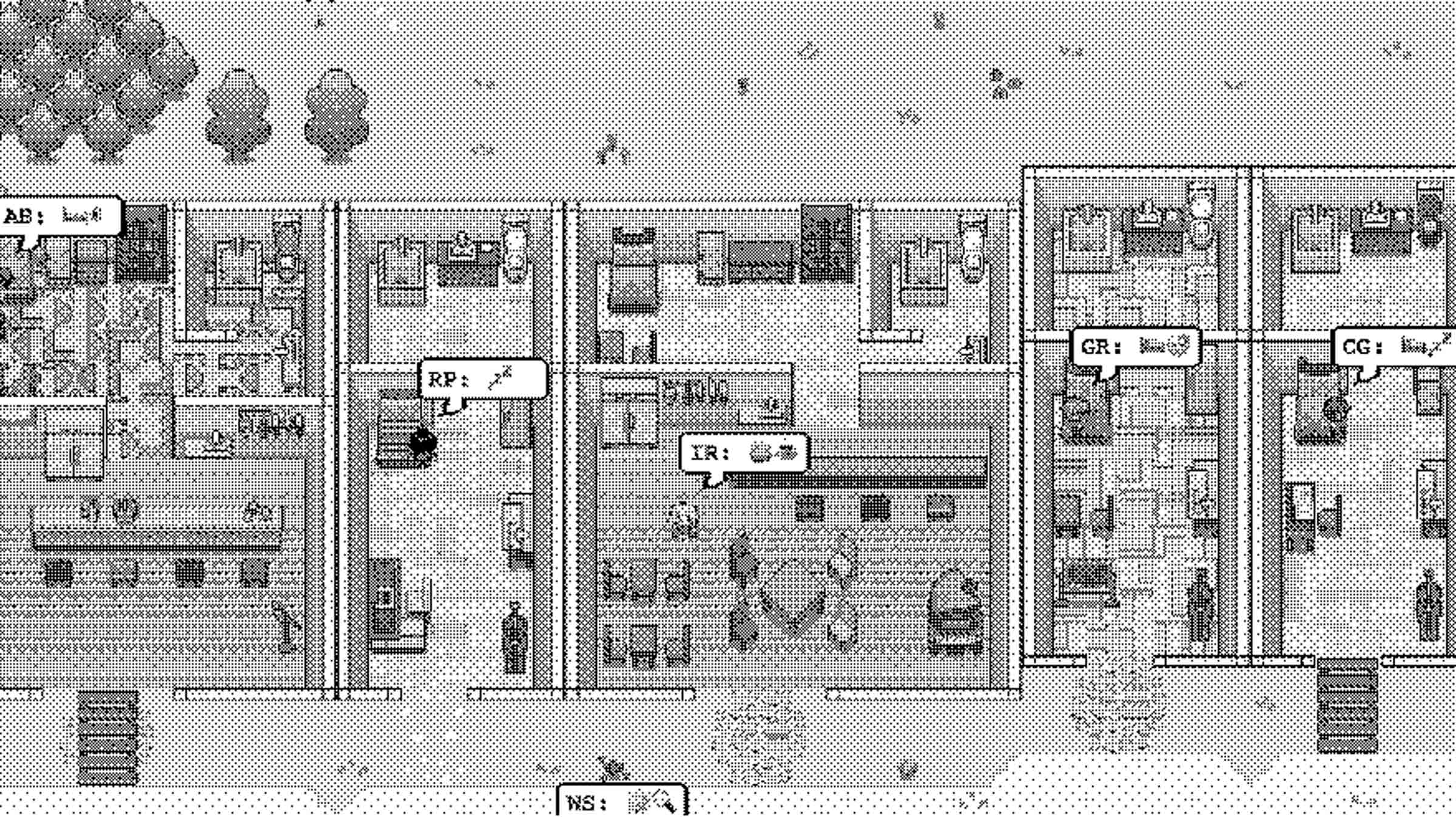

From Westworld to The Sims, the idea of fictional towns populated entirely by autonomous agents has long captured the public imagination. Now, researchers at Stanford and Google have teamed up to make it more of a reality than ever before, using the powerful natural language model ChatGPT to create 25 generative agents with pixel-art avatars, and putting these little digital humans—each with their own personality, hopes, and dreams—together in a Sims-inspired town called Smallville. The results are surprisingly wholesome: “Generative agents wake up, cook breakfast, and head to work,” write the study’s authors. “Artists paint, while authors write; they form opinions, notice each other, and initiate conversations; they remember and reflect on days past.”

Not only do these characters record memories, but they also channel them into believable behaviors, performed in an open world; on an interactive website, you can watch them brush their teeth, drag themselves to work or yoga, flirt, and make friends, even coordinating with one another to facilitate group social events when the opportunity presents itself. For instance, when one agent suggested they throw a Valentine’s Day party, the bots decided to send out invitations, asked each other to go as dates, and debated on when to show up. (The attendance, too, was realistic: only five of the 12 agents invited actually made it, with several of them citing “schedule conflicts.”)

This kind of emergent social behavior, carried out autonomously by different iterations of ChatGPT, is part of what differentiates this experiment from traditional game environments, where avatars must be hard-coded to carry out interactions. But rather than being guided by decision trees or other “brute force” scripting methods, the virtual agents in Smallville not only populate the town with realistic interpersonal phenomena; they do so autonomously, calling on experiences to inform their behavior in the moment, without the need for outside prompts.

In Smallville’s beginning, each agent was given a seed memory: a one-paragraph description, authored by researchers, that outlined their backstory, profession, relationships, and goals, from which emergent social dynamics then grew. For instance, when one agent told another his intent to run for mayor, it soon became the talk of the town. They even talk shit about each other! (“I’ve been discussing the election with Sam Moore,” said one agent, Isabella—to which another responded: “To be honest, I don’t like Sam Moore. I think he’s out of touch with the community and doesn’t have our best interests at heart.”)

“The virtual agents in Smallville not only populate the town with realistic interpersonal phenomena; they do so autonomously, calling on experiences to inform their behavior in the moment.”

The study introduces new possibilities for the simulation of human society. But the realistic behavior of these agents also poses ethical concerns, including the risk that humans will form parasocial relationships to them. This could be partially mitigated, researchers say, by instructing AI agents not to make or reciprocate inappropriate confessions of love. (Looking at you, Microsoft Bing.)

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI is well-documented, dating back to the world’s very first chatbot, ELIZA, a rudimentary language model that nevertheless provoked powerful emotional responses in its users. Today’s iterations, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, are much more sophisticated, having been trained on large swathes of online data—the result being a natural language model that’s as adept at writing code as it is at passing business exams, and even administering therapy. So, too, is it capable of engaging in compelling dialogue, from the intellectual to the sexual: A myriad of Replika users—an AI companion app which runs on a modified version of ChatGP—not only engage in erotic roleplay with AI, but consider themselves married to their chatbot confidantes.

While the realistic behaviors of these generative agents pose potential problems, they could also be powerful tools with which to “rehearse difficult, conflict-laden conversations”—a premise that recently surfaced in pop culture with the TV show The Rehearsal, in which Nathan Fielder commissions extravagant sets, hires actors, and practices dialogues with his clients, all with the stated intention of helping them stick the landing in real life. The show is farcical, but there’s evidence that mental rehearsal does, in fact, prepare people for action—so role-playing with highly realistic autonomous agents may well have an impact on your ability to navigate tricky scenarios IRL, from breakups to job interviews.

Designers could also use the program to power realistic robots, prototype dynamic, complex interactions that unfold over time, or use the large language model to test social science theories. And while the finer points are still in the works—agents have been found to occasionally embellish their memories, for instance, among other minor pitfalls—the trajectory of generative technology indicates that, if ChatGPT can perform a task passably well, it can learn to excel. According to researchers, the success of projects like Smallville opens up the possibility of creating “even more powerful simulations of human behavior,” which could be used to better learn, interact with one another, and create new ways to play.