For Document’s Fall/Winter 2023 issue, McKenzie Wark grapples with society’s love for identity-making, imagining a future free from flags or labels

At the Pride march, it felt good to be part of something amid the bobbing heads and waving banners. Only, I didn’t know what some of the banners meant. I asked my girlfriend Jenny, and she didn’t know either. We got on our phones and searched for “Pride flag” infographics. The one I found belonged to Volvo. With its help, we could distinguish the bisexual flag from the pansexual one and the lesbian one.

M: “Which one do you identify as?”

J: “Just gay, or queer, maybe. You?”

M: “If I have to have an identity, trans.”

I don’t know whether I want an identity at all.

When I was a teenager, I wanted to be a poet. I wanted to plumb the depths of my fathomless self. So I read the poet who I thought had done that: Arthur Rimbaud. His genius struck early (as I secretly hoped mine would, too). My identity, or so I thought, was “Poet.”

There were a few problems. Not the least of which was that I didn’t have any talent. And then there was Rimbaud himself. As he wrote in a famous letter, “I is an other. If brass wakes up a trumpet, it isn’t to blame. To me this is evident: I give a stroke of the bow: the symphony begins to stir in the depths or comes bursting onto the stage.”

Poetry, for Rimbaud, didn’t come from one’s identity at all. That was a laughable egoism. “I is an other.” It’s as seemingly ungrammatical in his native French as it is in English. Whatever I imagine is my identity is already something else—a displacement. I’m not there, in the place I think I am. If I write from the I what I write is always a fiction.

Poetry, writing—those don’t come from an identity at all. Rimbaud’s method was a “derangement of the senses,” a subtraction of identity. To get back from the trumpet of the self to the brass. So that when the poet writes, there will be no conscious intention. The poet gives a stroke of the pen, and the vast otherness of the world resonates through language.

A lot of artists took Rimbaud’s advice. He was revered by surrealist and situationist avant-gardes. In English, he’s known through the little paperback edition of his Illuminations, translated by Dadaist poet Louise Varèse. Patti Smith made a pilgrimage to his childhood home. David Wojnarowicz made photographs of himself around New York in a Rimbaud mask.

I figured out I was a terrible poet, eventually. I switched to prose. In my 20s, I decided that if I couldn’t be a poet, I’d be a “theorist.” I was still deranging the senses with drugs and dancing, but I was also staying up all night reading dense theory texts. With their methods, I thought I could crack the code—not of the mysteries of life, but of the structures of power.

A self-described “nasty street queen” of my acquaintance—upon deciding that I wasn’t worth fucking—thought that I might be worth educating. She pulled a crumpled photocopy of Michel Foucault out of the back pocket of her Levi’s and gave it to me. It was from a book later known in English as The Archeology of Knowledge. With my shaky French, I did my best to translate. It turned out that Foucault, not unlike Rimbaud, was not interested in identity, either.

To an imaginary critic who is asking him to identify himself, Foucault responds: “What, do you imagine that I would take so much trouble and so much pleasure in writing, do you think that I would keep so persistently to my task, if I were not preparing – with a rather shaky hand – a labyrinth into which I can venture, in which I can move my discourse… in which I can lose myself and appear at last to eyes that I will never have to meet again. I am no doubt not the only one who writes in order to have no face. Do not ask who I am and do not ask me to remain the same: leave it to our bureaucrats and our police to see that our papers are in order. At least spare us their morality when we write.”

“Whatever I imagine is my identity is already something else—a displacement. I’m not there, in the place I think I am. If I write from the I what I write is always a fiction.”

It’s an ironic passage, given that Foucault is at once refusing to identify himself while giving the game away. To anyone in the know, he is describing the experience of cruising in spaces not unlike the maze of glory holes in the back of Numbers on Oxford Street in Sydney, where I met my street queen acquaintance who went by “Keith” when she was there. Who I happened to know went by “John” in the establishment next door.

The poet gets out of identity so that she may let the wild world into language. The theorist gets out of identity so that she might pay attention instead to the institutions of power that produce, classify, rank, discipline, and also punish identities. Foucault was wary of identity because, for him, we’re all encouraged to do the work of institutions for them, by classifying, ranking, and disciplining ourselves.

Later in my 20s, having been disabused of the identities of Poet and Theorist, I nevertheless still thought of myself as a militant, as a political being. I went to the meetings, the marches, and the demos. I wrote about the causes of the day. That’s the context in which I read the statement of the activist-study group the Combahee River Collective. This was a group of Black feminists—some of them gay. They came at identity in a very different way.

They write: “We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women, this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.”

This came out of their experiences with Black men, working on Black liberation, and with white women, working on women’s liberation. The Combahee statement is the origin of the phrase “identity politics,” although it came to mean a lot of things beyond what they intended. Identity was their shared sense of being silenced—of needing to find others who also found it maddening that oppression could be present within liberation movements, too. This shared identity and sameness was only a first step. The second was a connection to others and to different experiences: solidarity.

This was the era when gay liberation adopted the pink triangle as a symbol—what the Nazis made homosexuals wear in the camps. Having read Foucault, this made me uneasy. Why would we do the work of oppressive power for it, and put the emblem on ourselves? Do we have to occupy the identities our enemies pin on us, and reverse their value? As if we could make a negative identity a positive one?

My other problem with it was—I had a girlfriend. I always felt gay, but I was attracted to women as well as men. Several of my girlfriends across this period were lesbians. That was confusing for everybody. What was my identity here? I felt like I could only choose from those that were visible around me. I was a somewhat effeminate man who regularly got called a faggot, and so thought of himself as one.

It didn’t really occur to me that I might be transsexual. That didn’t seem like a thing one could be. The gay male culture around me was making a point of separating itself from femininity. It saw the effeminate gay man as a harmful stereotype. It was the era of the gym body, the short hair, and the mustache. It was called the “clone look,” as if gay masculinity could reproduce itself without any reference to femininity. Although, of course, one still referred to everyone as “she,” a pronoun related to gayness more than gender.

I found transsexuality online. I was an early adopter of the internet. One of the reasons was that there were online spaces, as far back as the ’80s, where I could be a girl. LambdaMOO was an all-text, online space where one could write oneself as anything at all. There were six sets of pronouns to choose from, including “it,” the royal “we,” and gender-neutral ones. On LambdaMOO, I was she—and not in the gay male sense.

In the early days of the internet, nobody knew how to make all that much money from it. We were free to play. We had radical ideas of using it to circumvent the dominant media and create autonomous cultures of our own. It became a kind of identity. We could be poets, theorists, and militants all at once. We could create communication and community for identities that were marginalized and oppressed. For instance—transsexuals. I found my people.

This had its limitations. The trans people who were online were mostly middle-class and white. Many were not out at work, so it was a closeted world. Many internalized the way the medical institutions saw us, and made an identity out of pathology. There were exceptions to that, though. It’s an obscure book now, but it really expresses the adventures of the times: Kate Bornstein and Caitlin Sullivan’s Nearly Roadkill: An Infobahn Erotic Adventure, in which genders and identities are matters of artful play. I is an other, and another, and another…

The Italian filmmaker and theorist Pier Paolo Pasolini had a theory: When the revolution failed to overthrow capitalism, capitalism revolutionized itself. It became neo-capitalism. The distinguishing feature of which was that it did not just manufacture objects, it also manufactured subjects. The era of the mass production of consumer goods also mass-produced consumers.

To me, this seemed a useful correlate to Foucault. My identity was certainly shaped by school and clinic. (I was in hospital several times as a child.) My identity was shaped negatively by prison. It was the institution I knew I had to avoid as someone whose sexuality and drug use weren’t legal. But my theorist self thought it clear that I had mostly been made by television, pop music, movies, and magazines. Even my most radical desires expressed themselves via media stories and images. My favorite TV show as a kid was The Adventures of Robin Hood. Sure, I’d read Marx, but to the tune of the theme song from that show: “Steals from the rich, gives to the poor, Robin Hoooooood!”

The internet seemed, at first, like a way out of being the kind of subject manufactured by neo-capitalism to consume its products. And maybe it was. There are histories still to be written about what I call that “silver age of social media.” (It will have no golden age.) What happened instead was that neo-capitalism—or maybe neo-neo-capitalism—caught up with us. The internet became a way to manufacture identities that correspond to the labor and consumer needs of whatever this current information economy has become.

These days, the manufacturing of identity has been outsourced. We have to do all the work ourselves. We have to make both public and private simulations of the “self” on various platforms. I have my “professional” profile on LinkedIn as a professor. I have my middle-aged, semi-professional one on Facebook. I was on “trans Twitter.” I try to look cute on Instagram. These are all slightly different identities, crafted for different purposes. I was on eight dating apps for a while (nine if you count Twitter). I was not the same person on Tinder as I was on Grindr.

This isn’t entirely new. The social psychologist Erving Goffman wrote, a long time ago, about how we appear differently depending on how and to whom we frame ourselves. You are a different person when telling your big night out story to, say, your best friend, your mom, or your boss. The new part is how the mediated production of images and narratives of the self has become such a big part of an information economy.

Some would call this “neoliberalism,” but I find it more useful to think that we’ve all become gamers. We get to pick the skin for our character, but then we have to go out in the gamespace of the world, as if it has to be a zero-sum contest of winners and losers. It’s a media infrastructure designed to steer us away from solidarity. The way this makes me feel crazy is a design feature of this information economy, rather than my—or your—personal failings. My mental health diagnosis does not have to be an identity. It’s the game itself that is not rational or compassionate or fair or even human.

Those of us who always felt alien to dominant forms of identity sometimes acquire next-level skills in identity-making. I passed as a straight(ish) cis white man for much of my life, so I wouldn’t center myself as an example. I see it around me in people who have had to pass through the world as, for example, Black and trans and femme all at once. Crafting identities can be a survival art.

The old neo-capitalist economy manufactured sameness in both its products and its consumers. It was a conformist time, as I remember only too well. The fashions changed only four times a year. The current neo-neo-capitalist economy manufactures difference at a much faster rate. It needs to discover and extract every last morsel of every specific identity, as fast as it can. It’s still owned and controlled by the most basic-looking white guys you ever saw, but it needs those of us who have other, more flavorful identities to add spice to the tumultuous turnover of products.

This is making a lot of not-so-rich basic white people very angry. Their identities got sucked dry a long time ago. Much of the product will still be for them, but it’s not all about them anymore. So some of them have found a way to reverse-engineer the information economy of difference. According to them, they are the ones who are oppressed—by “wokeness.” They are the ones who don’t get to feel special anymore when they tell their little racist jokes. Social media exposes the extent to which many people’s identities are nothing more than hating someone else, to whom they want to feel superior.

“We get to pick the skin for our character, but then we have to go out in the gamespace of the world, as if it has to be a zero-sum contest of winners and losers. It’s a media infrastructure designed to steer us away from solidarity.”

In New York, there’s even an attempt to make this all seem cool. Publicists are working hard to concoct a Dimes Square avant-garde of crypto-fascist trend-makers. It’s not exactly a formula for good art. I is an other. I still think Rimbaud was right about that. Good art does indeed start with the kind of difference that sets you apart—Rimbaud was homosexual. But it doesn’t turn that into an identity. It keeps going from that outsider feeling, and goes further out.

Likewise with any theory of culture. Both Foucault and Pasolini knew that the world in which they lived considered them homosexual, with all the stigma that dominant culture loads onto that. They pushed from that difference to an analysis of how the entire social and technical machinery around them operated. Likewise with any politics. As the Combahee women knew from experience, identity was just the start. The next step for them was solidarity, based on mutual recognition of different identities, and the forms of oppression felt by each.

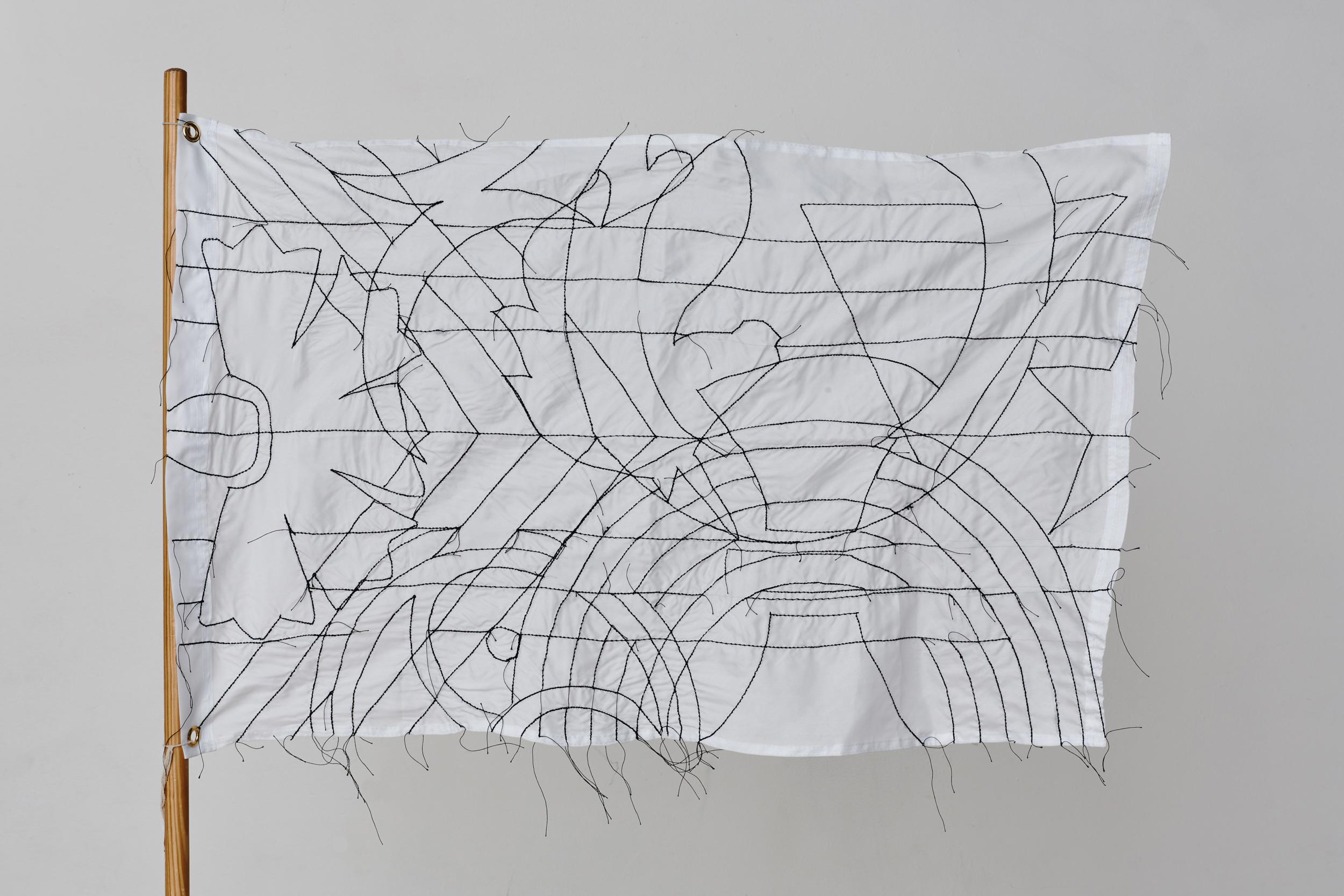

It’s not liberation that we all have to make our little profiles, and wave the little flags to which we’re entitled. I don’t put the trans flag in my profile for the same reasons I don’t put the Australian flag. Once you have a flag, you have arguments at the border about who is allowed in and who is to be kept out. Which also leads to the splitting of identities. There used to be just one Pride flag. Now there are dozens. Which solves the problem of inclusion and exclusion in a way that makes it a fractal—each identity splitting into smaller ones that are different—but still of the same shape.

“Include me out,” as the saying goes. I want to wear my various identities lightly. But that’s because I can. It’s only fair that I cop to being a relentless self-promoter on social media at this point. I don’t think it’s a critique of this identity economy to do it badly. There’s a narcissism that social media exploits, but there’s also a narcissism in considering oneself above self-promotion, as if entitled to have the world do the work of discovering one’s genius. I came to New York as a provincial nobody. I had several advantages: native English speaker, extensive education, valid visa, full-time job on arrival. And I worked them for all they were worth, shamelessly.

There are haters who say I became a transsexual for attention. Actually, what happened is I started being taken far less seriously. As an (apparently) cis white man, my thoughts on big-picture questions were sought after, particularly on the “state of the media.” After I came out, I was mostly asked about trans stuff, even though I am still a professor of media studies who wrote several books about that. This is the trap of identity. Before, I got to speak about the general. Now, I get to speak about my own particulars.

There’s a short circuit where identity alone is supposed to guarantee a valid perspective. Meanwhile, basic-ass white people, and people whose difference doesn’t set them too far apart, get to talk about the “important,” supposedly more central issues. Just look at who gets on the editorial page of the New York Times. Some identities get no space to speak about the big picture. Some are not even allowed space to speak for themselves.

One of the struggles of the post-Civil Rights era is getting those with discounted identities to speak, at the very least, about their own experiences. “Nothing about us without us,” as disability activists say. Trans people are among those not yet always granted that in the public sphere. The New York Times, the Atlantic, New York Magazine, and the Guardian regularly publish pronouncements about us from people who seem not to have even met us.

The visibility of “transgender” as an identity category has turned out to be a two-edged sword. Black trans people warned us about this all along. The visibility of transness helped me, and many others, come out. It also made us a target. People who did not realize we were an identity they could hate are making up for lost time. I’ve lost track of the attempts to legislate us out of existence in the “red” states. British culture, which gave us so many wonderful things, from mod to punk to grime, now seems to have nothing to export to the world but its transphobia.

Still, the most interesting writing, art, and politics seem to me to start from an identity that experiences itself from the outside, as other to dominant identities. It doesn’t model itself as another version of the norm. Rather, it subtracts itself from the grid of identity altogether. This is why I pay attention to Black writers and artists. Their standpoint is outside mine. I learn from that gap. It’s also what I pay attention to closer to home, among trans writers and artists. I don’t want that to harden into an identity with rules and borders. I think we learn more when we’re not all on the same page. And we have more fun.

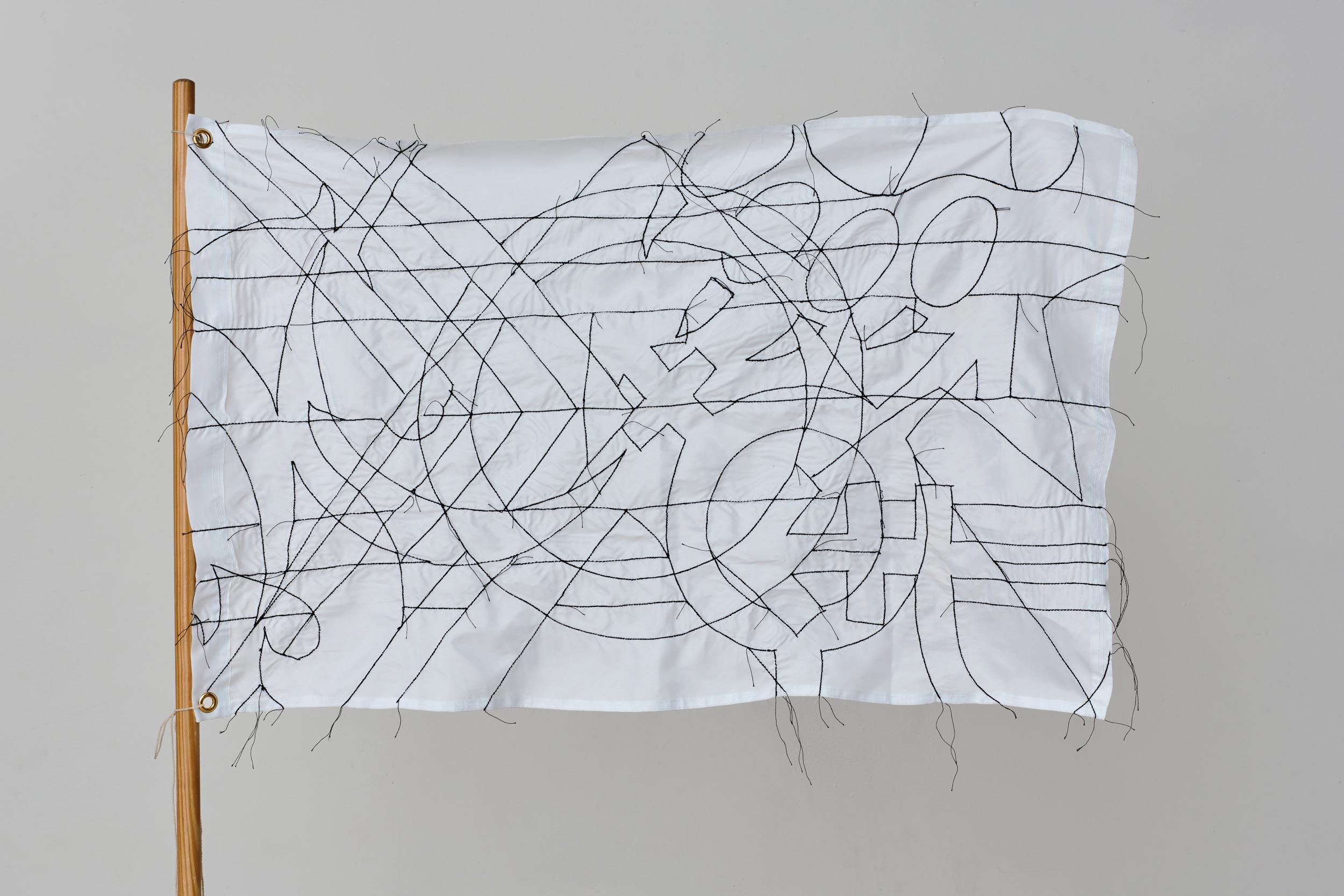

First, find an identity; second, step away from it; third, come together to get free. Next Pride, I want a flag of clear plastic, with nothing on it, so you see everyone else through it—its prism refracting all the colors you can see, and even some you can’t.