For Document’s Fall/Winter 23, writer Daniel Gumbiner explores life, death, and industry in the state’s largest necropolis

When I moved to New England for college, I was surprised to see old graveyards in the center of towns and cities. It occurred to me that I almost never saw graveyards in San Francisco, where I was born, or in the small town in Northern California where I grew up. The only graveyard I had ever really visited was a military one, in the Presidio in San Francisco. There are, I would come to learn, historical reasons for this. The majority of San Francisco’s dead lie in Colma, a vast necropolis 10 miles south of the city. Colma is home to approximately 1.5 million graves and just 1,507 living residents. The town—which also boasts a thriving auto sales industry and a casino—sits on a plateau at the base of the San Bruno Mountains. By all accounts, the people who live there love it. The town slogan? “It’s good to be alive in Colma.”

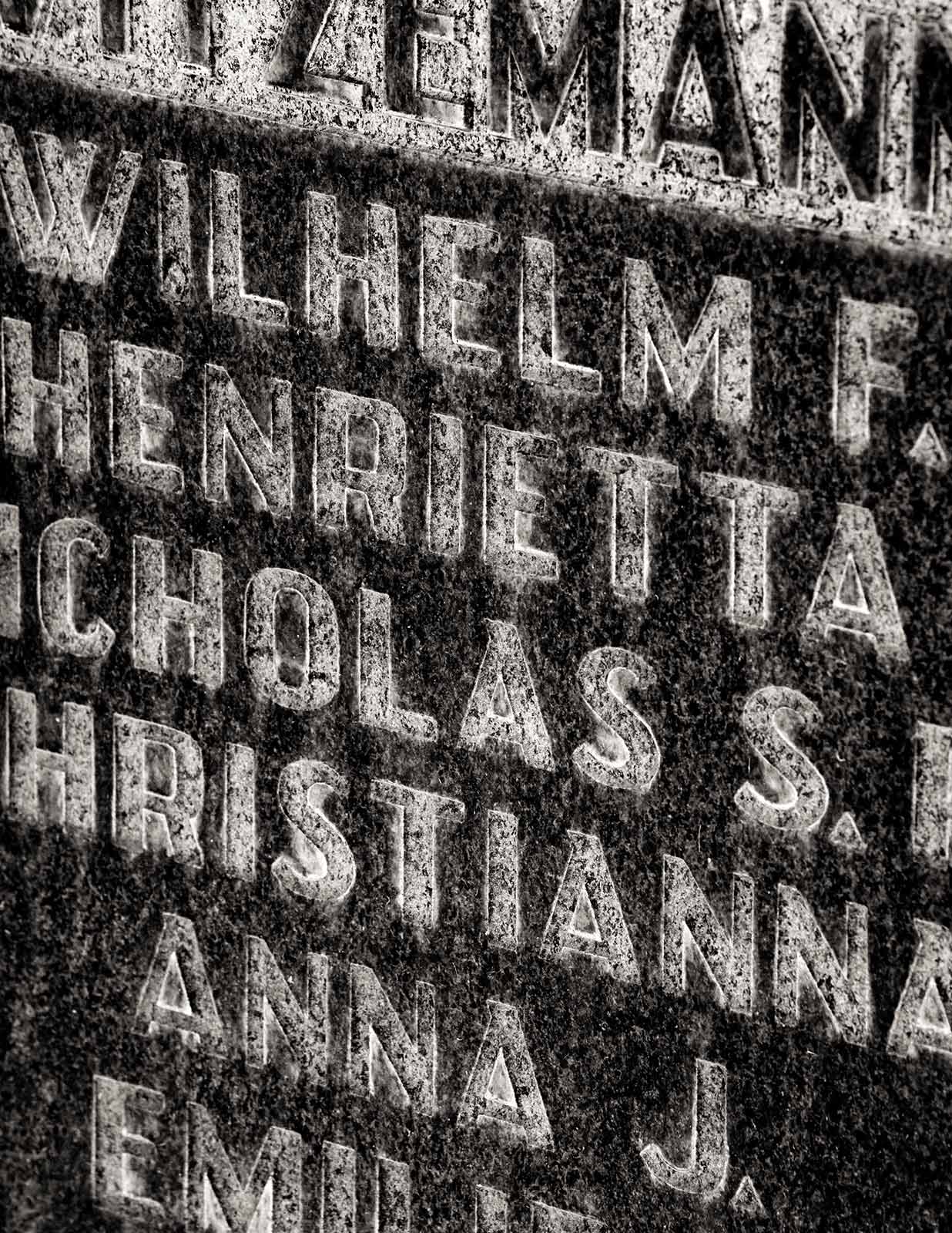

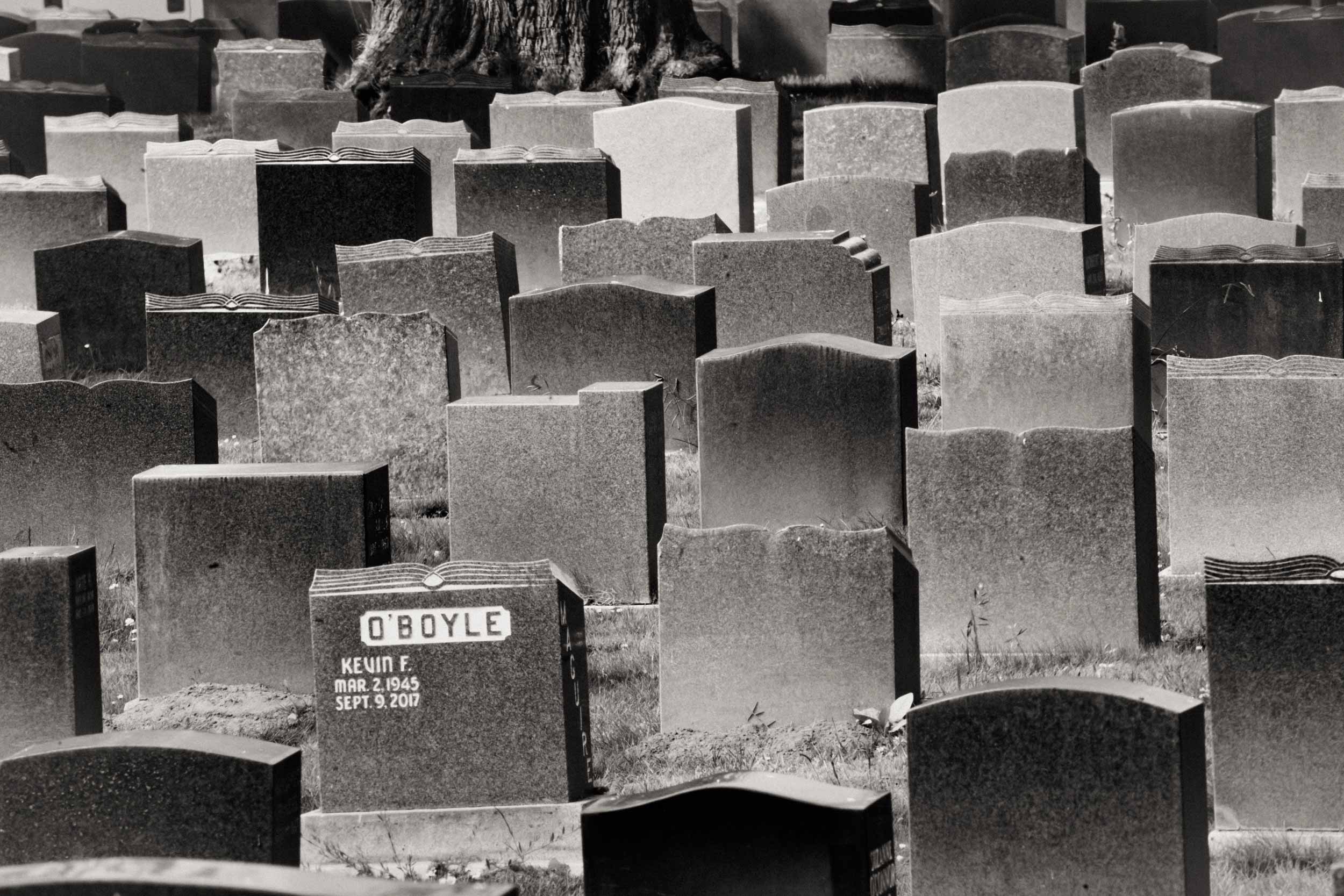

This summer, I visited Colma for the first time. From my home in Oakland, I drove across the Bay Bridge and south along Highway 280. It’s easy to tell when you’ve entered the town: Gravestones are everywhere. They spread in smooth arcs over the gentle hills, like vines in a vineyard. Some of them are ornamented with pinwheels or American flags or flowers. Burly, fog-drunk cypress trees dot the sloping green lawns. I passed plots that were for sale, ornate mausoleums, granite monuments. There are many famous people buried in Colma, including Wyatt Earp and Joe DiMaggio. But more impactful than the stars, to me, was the sheer scale of the cemeteries. Almost everyone who lived and died in the city where I was born ended up here.

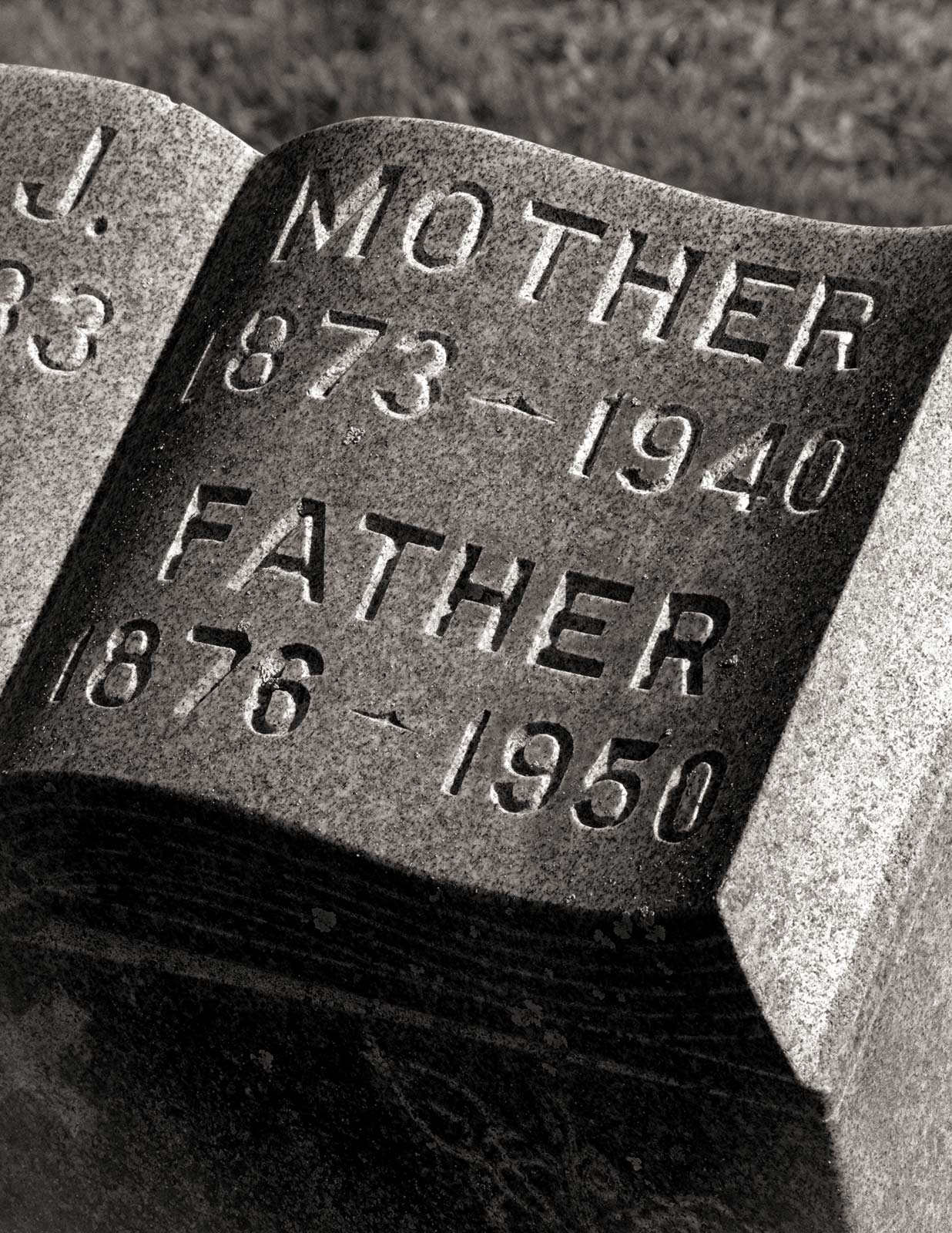

A cemetery is the archive of a community. A place where stories layer on top of one another. And yet, in America—and especially in the West—our graveyards have largely been moved out of sight, to the periphery. It is hard not to see the parallels with our country’s elder care, the way we ship our senior citizens off to assisted-living facilities. Aging and death are difficult to confront. Elizabeth Kubler Ross, in her seminal book, On Death and Dying, wrote that “Death is still a fearful, frightening happening… even if we think we have mastered it on many levels.” But what is it like to live more closely with the dead? What can we learn from a place like Colma?

“When I moved to San Francisco in 1970,” Maureen O’Connor told me, “I never thought about the fact that there were no cemeteries.”

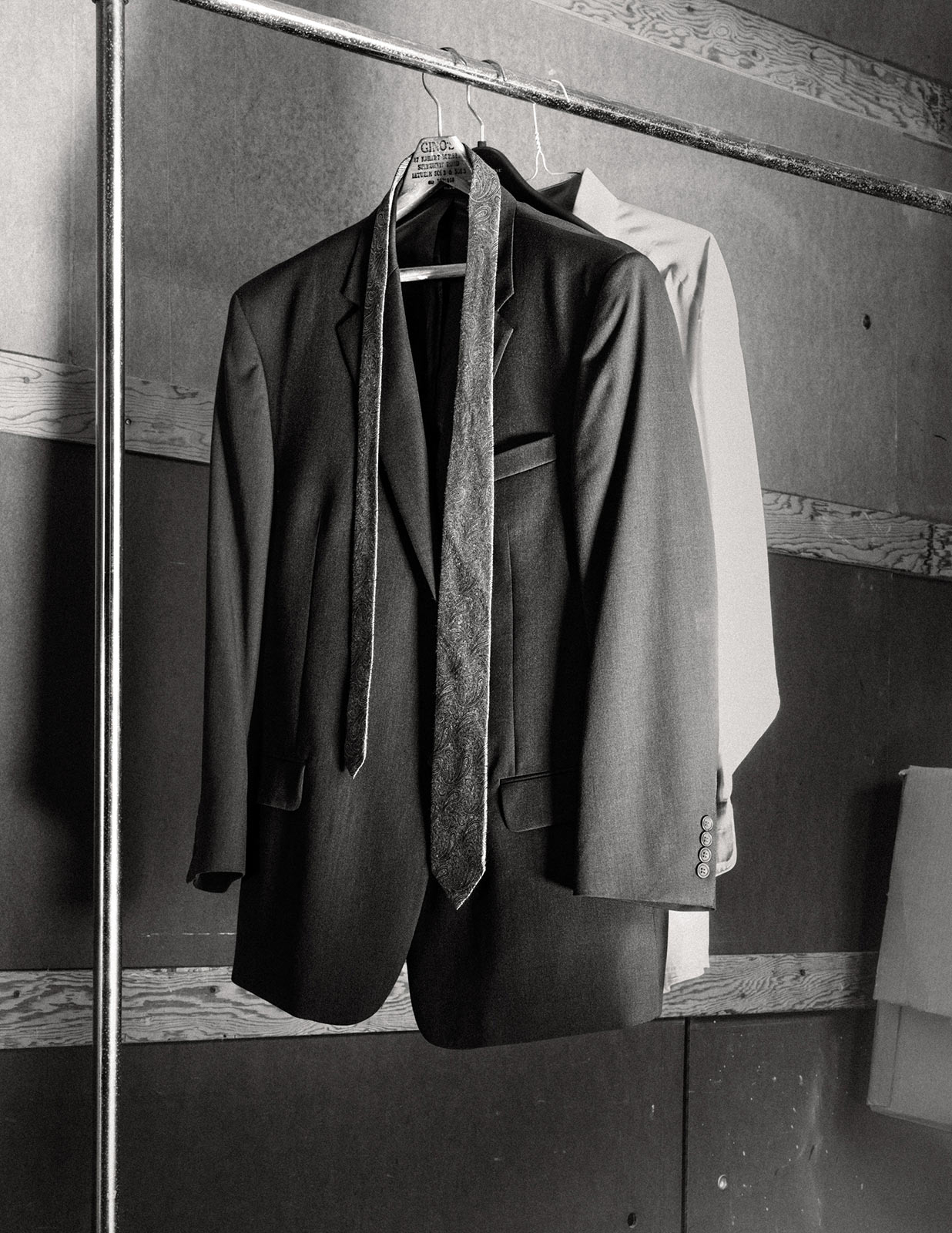

O’Connor is the president of the Colma Historical Association and a longtime resident of the town. During my visit, she showed me around the Colma Museum, which features an extensive collection of historical odds and ends, including the town’s first computer and a “sample casket.” We sat down in the back office for a longer conversation.

O’Connor told me that she moved to Colma from the city in 1981, because it was an affordable place to live. At the time, she didn’t exactly realize that she was moving to a necropolis. She started taking long walks in the cemeteries, and over the years became fascinated by the town’s history. She said the cemeteries reminded her of home—she’s from Metairie, a suburb of New Orleans—and she liked having access to all the green space. I asked her what it’s like to live so close to so much death. “In terms of talking about [death],” she said, “I’m much more willing than most people. It kind of spooks them out.”

“A cemetery is the archive of a community. A place where stories layer on top of one another.”

O’Connor said that living in Colma, surrounded by the presence of death, has influenced her way of being in the world. She recounted a piece of advice a friend and fellow Colma resident once gave her, when she was feeling anxious. “Look out there,” the friend said, gesturing to the graves by her house. “Those people don’t have to worry about anything anymore.”

There is a natural and easy depth that emerges in conversations in Colma. Within the first hour of meeting each other, O’Connor and I were discussing our opinions on the afterlife: “Death is a total surrender,” she told me. “You just jump off a cliff.” But there is also an odd normalcy to life there. Wandering around the museum, looking at photos of the local firemen and the original elementary school, I felt like I could be in any small California town.

This was perhaps best exemplified when I asked O’Connor what the most pressing issue was in Colma these days. I was curious about what residents were actively debating—if there were any big controversies. After a long pause, she said, “Parking.”

San Francisco was, at one time, home to several cemeteries. In 1900, however, the Board of Supervisors put an end to new burials. The cemeteries were overfull, and many believed the decaying bodies constituted a health hazard. Fourteen years later, the Board ordered that all dead bodies be removed from the city. In addition to the threat of disease, the land the cemeteries occupied was valuable, and developers wanted to use it for residential and commercial purposes. The dead were disinterred and relocated to Colma, which was only a day’s journey away. If families couldn’t afford to pay the $10 relocation fee, their loved ones were buried in mass graves—which you can still see throughout Colma. Some of the headstones that were removed from San Francisco were reused by the city for various purposes, including the construction of storm drains and the sea wall at Aquatic Park.

This decree was part of a broader drive in America to develop “rural cemeteries.” Like the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, many believed that by removing dead bodies from population-dense areas, they could reduce the spread of disease. Most expanding cities were also running out of space to inter the dead. As a result, new cemeteries were built on the outskirts of major urban centers—in Cambridge and Brooklyn and Colma. Despite the fundamentally practical origins of rural cemeteries, their architects took the opportunity to design them in a way that encouraged spiritual reflection. The Transcendentalists loved them for this reason. Their giant entry gates—the kind of gates you can still see in Colma—signified to visitors that they were, for a moment, leaving the temporal world behind. Their British-style gardens were meant to be paradisiacal.

When the first rural cemeteries were built, they were the envy of the world. European writers such as Charles Dickens wrote home in admiration of them. Local residents—who apparently did not fear that the bodies might transmit disease—flocked to their grounds on the weekends and during holidays, for picnics and recreation. As Keith Eggener, the author of Cemeteries, documented, this was in part because, at the time most rural cemeteries were developed, cities had few public parks, and the new cemeteries functioned as de facto green spaces. They were so popular, in fact, that some cemeteries had to institute “lot-holder days,” in which only people with family members buried on the premises were permitted to visit.

But another consequence of the rural cemetery movement was the degree to which they removed the presence of death from everyday urban life. As Eggener writes, “Well into the nineteenth century the division we now maintain between space for the living and the dead did not exist.” This division largely remains in place today. Many Bay Area kids—like me, for example—grow up without ever visiting Colma. Or if we do, we come for a funeral and then we leave. The death industry—like so many things that make us uncomfortable—has been outsourced.

“Death may have been pushed to the periphery of urban life in many ways, but in Colma, it makes itself known.”

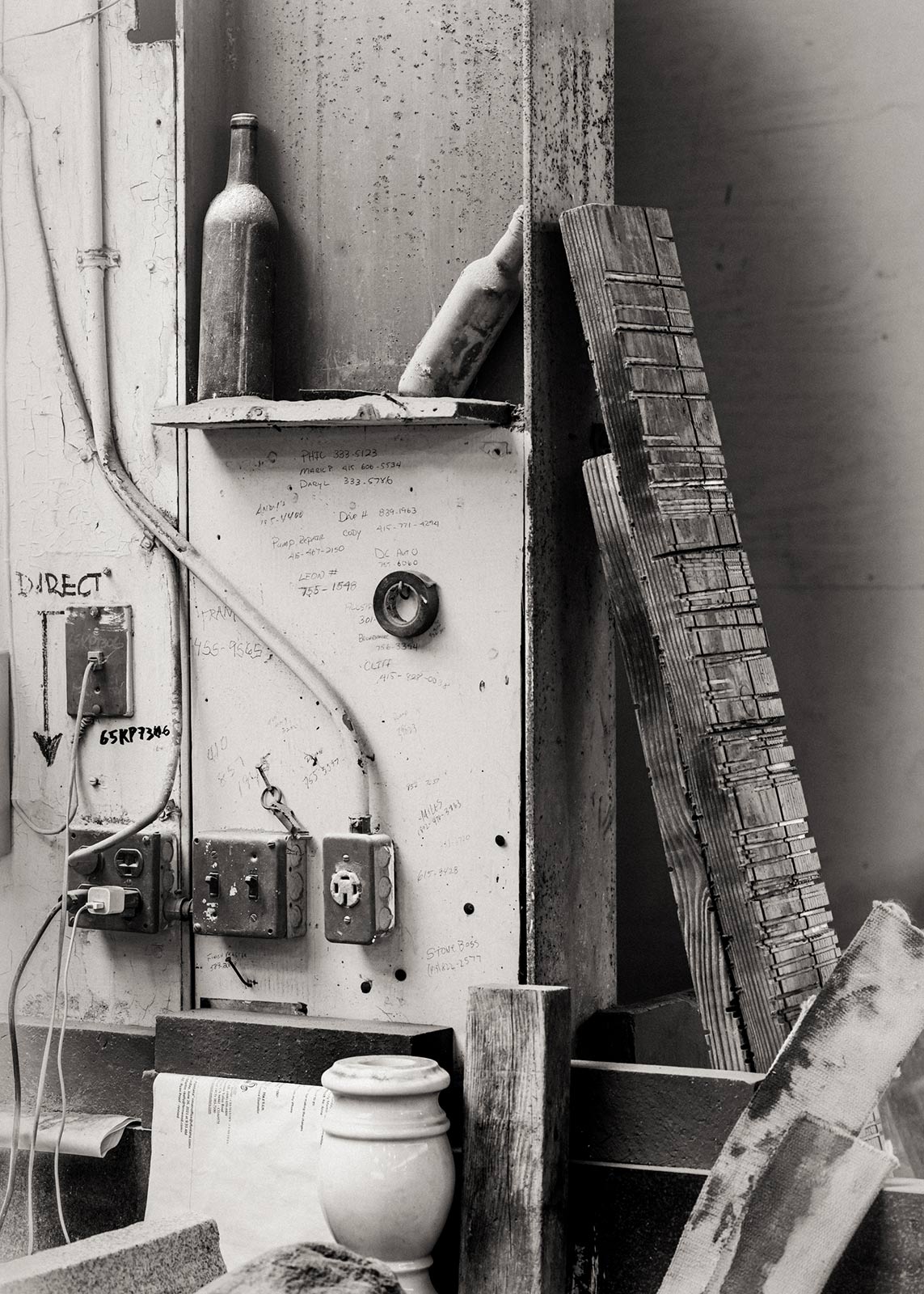

V. Fontana & Co. has been making monuments in Colma since 1921. Their workshop is located right next to the Italian cemetery, and it’s filled with huge slabs of granite. There’s brown granite from the Dakota Mountains, blue granite from Norway, gray granite from the Sierra foothills, and several different kinds from India. The workers use a giant diamond-wire saw to cut particularly big slabs, and a couple of different machines to polish.

“We make everything,” Phil Fioresi, the shop foreman, told me. “We can do whatever.”

The multigenerational company is now run by Mark Fontana, whose grandfather came to San Francisco at the turn of the 20th century, along with many other Italian stonemasons. Like his grandfather before him, Fontana lives above the company office with his family. When I visited, he had just finished making his daughter an omelet. He showed me the back patio, where scores of friends often gather for long Friday dinners, and the kitchen, which is covered from floor to ceiling with photos of loved ones. In the basement, Fontana makes sulfite-free wine with grapes from Calaveras County. He handed me an unlabeled bottle to take home.

“When you open it,” he said, “you gotta let it breathe.”

Working with monuments in Colma, Fontana told me, puts him in contact with many different kinds of people. He tries to honor every family, but to do this, he has to figure out what they want. So Fontana asks a lot of questions, and tries to get people to talk about their loved ones as much as possible.

“This is the final thing that anyone ever does for their friend or family member,” he says. “This is it.”

After years in the death industry, Fontana treats the end of life with a casual acceptance. He says he doesn’t think about it too often. His grandfather is buried in Colma (his father made the monument), along with many of his family members. Fontana goes by their memorials every once in a while and leaves them flowers. I gestured at the thousands of photos covering the kitchen walls, and said it seemed like, in a way, his whole house was a kind of monument to his loved ones.

“It is,” he said. “I try to keep their memory alive. People who are not around anymore can still live on.”

The American rural cemetery movement morphed into other movements, ushering in “lawn cemeteries” and “memorial parks.” But in most cases, future burial grounds remained separated from urban development. “Increasingly,” Eggener writes, “[cemeteries] became places of the dead almost exclusively, as the living preferred to avoid them except when absolutely necessary.” The designers of rural cemeteries did not intend to excise death from the world of the living—they wanted to honor the dead and solve certain practical issues. But design sometimes has unintended consequences, especially many decades down the line.

To sit in the presence of death is to consider our own mortality. And this is, of course, a frightening experience. Often, because of this fear, we shy away from death. Try not to look at it too closely. In some cases, our own fear leads us to see the process of aging as something that must be resisted—as opposed to the completely natural and inevitable part of life that it is.

To spend time in Colma is to more actively engage with the facts of life and death. Today’s Colma is shifting in various ways—there are more corporations, more green burials—but it remains an archive of community. It is a place of both dramatic and subtle beauty. A place for people to grieve and to remember. Death may have been pushed to the periphery of urban life in many ways, but in Colma, it makes itself known.

On my way out of town one day, I stopped at Molloy’s, a vintage working-class, San Francisco-style Irish pub, located across the street from the Holy Cross Cemetery. Above the bar, there were drawings of the city and jerseys from local Catholic high school sports teams. Mourners often stop here after a funeral to drink and talk about their loved ones.

I ordered a coffee and chatted with Pat, the bartender. I met an older ex-Marine whose parents used to run a funeral parlor in the Mission District, and he told me a somewhat convoluted story about a time he partied with Carlos Santana. There were a few other guys in work clothes hanging out and a couple of people who looked like they’d just come in from one of the cemeteries.

Later on, I was introduced to Owen, one of the owners, whose grandfather founded the bar in 1927. He said Colma was a great place to grow up—a small, close-knit town. His father was raised in the apartment above the bar, and Owen lives just down the street. He told me he works there every day.

“It’s a neighborhood bar,” he said. “We got a lot of regulars. A lot of great clientele.”

Eventually, the conversation came around to the question of death. I asked Owen what insight could be drawn from living around so many burials. His answer came quickly: “You’ve got to live the best life you can.”

I told Owen I’d bring him a copy of the article I was working on, headed out the door, and hopped in my car. As I started to drive away, I could see San Bruno Mountain in the distance, its peaks dotted with radio towers. For a moment, I got a bit lost, but then I found my bearings. I felt awake and fresh. Maybe it was all the coffee. Off to my right, I passed a Costco. Growing up the side of its giant cement wall was, I kid you not, the most riotous bougainvillea I’ve ever seen. I pulled off to the side of the road to check it out.