Rachel Rabbit White explores the strip club's enduring fantasy of social and sexual upward mobility, both on-stage and off

Any girl who has dropped into a gentlemen’s club to make some cash has had to deal with that first order of business: What’s your stripper name?

“I don’t think we have one of those right now,” the manager might trail off in response to your suggestion, his mind working to recollect the various Skylas, Ninas, Nikkis, Bebes, Brookes, and Kikis who had marked their names on dressing room lockers.

As for the strip clubs themselves, you see the same words come up again and again in different formations: Diamond, Dream, Fantasy, Mirage, Exotic. These, like the stage names of the girls who work them, are meant to evoke a certain mystique—one that stands out without veering too far from the expectations of the clientele.

No matter what dreams the clubs promise, what they hold is more or less the same: lap dances, mirrored walls to create the illusion of something bigger, a series of private rooms. And yet, the fantasy endures—the idea that this time, almost anything could happen.

A memory of working the clubs comes back to me: In the harsh overhead lighting of the dressing room, we were all eyeshadow, hair extensions, false lashes, and bottled scent, masking ourselves in the generic idea of feminine beauty.

“You’re all just drag queens when it comes down to it,” said the make-up artist appointed to put eyelashes on us for a $20 fee.

I didn’t entirely disagree with him, but I got the sense that no one much liked hearing that as we fussed over the details of the fantasy. After all, we had our own fantasy, too: that of upward mobility, the American Dream. That we could make it at Dream Playhouse, Fantasy World, Mirage Exotic. That this time, the promise would not escape us.

In Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show, Rachel Shteir traces the origins of the American strip club to 1827, during the Romantic Period, when ballet transformed into an art, performed by women for men. Madame Francisque Hutin was the first solo female ballerina to dance in New York City, shocking audiences as her semi-transparent skirt floated up, revealing her thighs and hips in an era when only prostitutes showed their ankles in public. This was a time when many theaters were situated next to brothels, and the association between the stage and sex work only strengthened as the two began to offer the same types of entertainment. Lines between vaudeville and burlesque blurred.

Styles of dance changed as American mores shifted, but the work has always been the same: For all the mystique and fake names, the job is to undress on a stage with some form of contact with the audience. Of course, there is more to creating the fantasy: the craft of the tease, the art of entertaining, and the possession of a certain quality—the “it factor,” a decidedly feminine form of charisma that is often described as indescribable, yet basically comes down to one’s attractiveness transcending physical looks. It’s sexual magnetism.

Getting a guy on the line is a striptease in itself, spiritually. You have to piece out your backstory—find the right moment within the seduction to flash a part of your spirit, then put it away again. Part of the tease is always about this, for all its mystery: letting them see the real you.

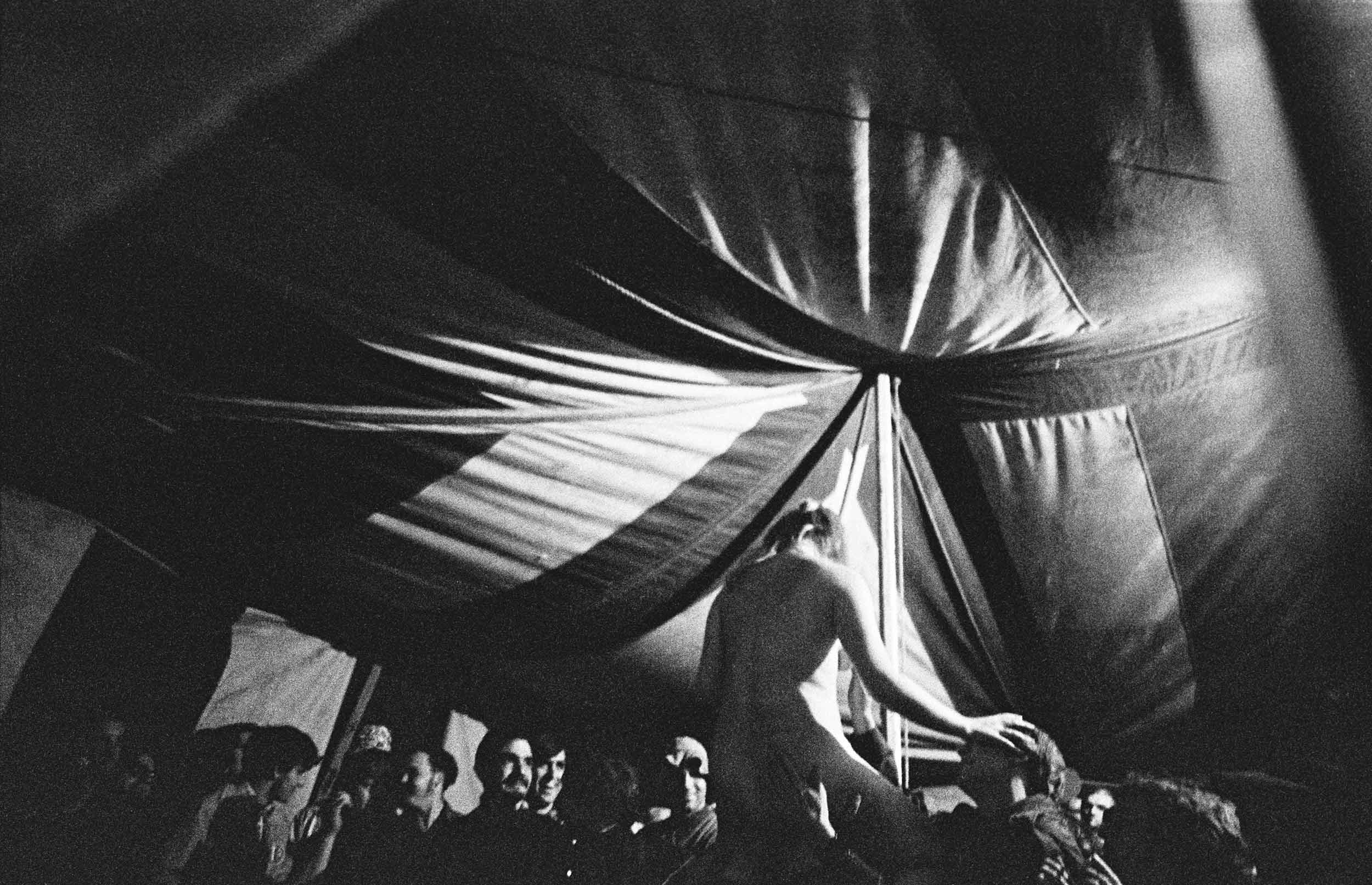

Susan Meiselas’s Carnival Strippers documents women who worked the girlie shows at traveling US carnivals in the mid-1970s. Most of the women had left small towns. Meiselas describes them as “run-aways, girlfriends of carnies, club dancers, both transient and professional.” It was in this strip circuit that the stripper pole is thought to have come about, as the women working the tents would hold on to the pole while they entertained the audience. Girls in the carnival circuit worked in the summertime. Come off-season, they might have hopped around the growing number of topless bars or hung out with bikers, who could always offer a ride to the next town.

There is an unavoidable transience to strip club work. In middle America, clubs are zoned out to the highways, and there’s always another to hit if luck runs dry. If you’re in a city, you can jump from club to club and take a gamble on the stage fee.

If the American Dream is about doing better for oneself, it runs parallel to another nostalgic Americana fantasy of hitting the road, traveling, and living one’s life outside the trappings of the nuclear nine-to-five.

“In the harsh overhead lighting of the dressing room, we were all eyeshadow, hair extensions, false lashes, and bottled scent, masking ourselves in the generic idea of feminine beauty.”

Part of the club’s ephemeral nature is the time spent waiting within it. Working any given shift, a century could pass, sitting on cushy swivel chairs, waiting for paying customers, No phones allowed on the floor. It could feel as if too much time had been fit into the night, or too little, depending on which way the spiral was moving. The unceasing flow of movement. Life as an entertainer means working long hours, sitting around in the liminal space of a bar, waiting for it to come to life—or else time off spent recuperating, resting, eating, sleeping, laundry, TV, talking, and again waiting.

There are always two ends of the pole: The strip club represents a place where one can find better opportunities for prosperity, regardless of social class. And simultaneously, it’s easy to see it as the first step in falling out of the social structure altogether. Maybe this is the case with any kind of erotic work—that would certainly explain the many novels and works of art about “fallen women” and their paternalistic moral instruction: From The Lady of the Camellias to La Traviata, from Nana to Dark Roots: The Unauthorized Anna Nicole, it’s all the same. Her body is worn down, she dies of consumption or dissipation. It’s never a happy ending for the woman who has fallen out of society, even if she elevated her social class in the process. The job is almost universally seen as an interlude, a stop on the way to falling back into society via a husband or an office job—or else a stop on the way to a tragic end.

As a stripper, there’s a tendency to think you’re only doing this for a while, even as you admire the women smart enough to build careers off leaning into the bit, into the job. Women have made fortunes for themselves, playing the role. Still, it’s hard not to think it’s only temporary when desire seems to have such limited forms. In the club, a girl hears the same lines again and again, night in and out: “But what’s your real name?” and, “Maybe you should pay me!” along with variations on, “You’re different. What are you doing here?”

It’s hard not to take offense, partly out of pride. “You’re different.” Are they saying this particular club isn’t good enough? Or that you’re not cut out for the job? Even when you know what they mean: That somehow, despite working in the strip club, you aren’t a stripper. Maybe this is key to the mystique built into the strip club—that it’s a way of seeing not only a woman’s naked body, but also her erotic imagination. Her desires, acted out. It seems to say, “You can want to be a stripper, but even if you work in a strip club, to be taken as an object of fascination, you can’t really be one.” They don’t want a professional.

Of course, for the strip club to be home to the American Dream, there have to be tales of success. In 1936, Gypsy Rose Lee was known as “the literary stripper,” an ironic character she invented as a way to poke fun at the academic New York City audience slumming it at her shows. Outside of work, she rode around in a chauffeured Rolls Royce with her initials painted in gold on the door, and as her fame grew, she broke into Broadway, wrote short stories for the New Yorker, and published a novel that would be made into a movie starring Barbara Stanwyck. As stars like Lee and her contemporaries—Sally Rand and Ann Corio—rose to fame and tried out Hollywood, they maintained to the media that stripping was an art form.

By the late-’60s, Corio, who started her career in the ’20s, and Rand, who performed at the Chicago Fair in 1933, were still stripping. As Shteir documents in Striptease: “In 1966 Corio performed at a tent show at the county fair on the outskirts of Baltimore. Women in the audience outnumbered men three to two. A photo of Corio from this tour shows her looking somewhat matronly, in chiffon, arms akimbo, giant diamond earrings hanging from her ears. In the background, the faces of country women of all ages, bespectacled and gray-haired, stare up at her in amazement and curiosity.”

By the ’70s, clubs that had once hosted the traditional burlesque striptease were transforming. While some dancers still performed in the outdated ’50s style, many venues had begun showing live sex acts, and topless go-go dancing became the norm. The girlie shows at rural fairs, like the ones depicted in Carnival Strippers (fully-nude, allowing “box lunch”—that is, a pussy lick for a tip, a precursor to the lap dance), made the stripper into a figure to be either pitied or hated.

In Carnival Strippers, Meiselas quotes a woman in the rural ’70s carnival audience, who laments that she feels sorry for the dancers: “They’re not intelligent enough to know that they could be doing something else, working in a restaurant or a factory or getting married and having a family—anything.” It’s the story we have to tell women, one that keeps the mystique of the strip club in the popular imagination—how it’s taboo, despite being an American institution, or maybe the American institution. Because what’s more American than offering someone a shot at independence, money, and a more comfortable life—but only if they turn themselves into a spectacle?

It can make a girl need a drink, staring at herself in the mirror against the wall while talking to customers all night. Until this moment, you probably don’t realize how you actually look when you’re talking or laughing, or doing anything other than making a “mirror face”—that automatic position the face settles into when confronted with itself.

Returning to the pages of Carnival Strippers: There’s a man who works on the circuit as a “talker,” who sells the girls to the audience. He opens up about his worries. He’s seen the girls, he knows the girls, and—while they aren’t psychotic—there’s something endemic about the “mental imbalances” that would drive them to this sort of work. He says, “The girls are what I call usable. They’re unable to defend themselves and a strong man or woman can take such ridiculous unfair advantage of them.”

Pages later, a man in the carnival audience offers his perspective: “In a way I look up to them. They’re not selfish. I think it’s hard to do what they do. They’re actually giving of themselves, they’re sharing, and they’re making people happy. They make me happy anyway. That’s about the most intimate thing you can do with a woman.”

It’s perspective, I guess. Either she’s a hooker with a heart of gold, she’s a victim, or, at worst, she’s a pro—a hardened hustler who only makes a drag of femininity. All the while, the reality of the situation on the other side of the dressing room door is one full of intertwined motives, dreams, and desires.

The measure of whether it’s a job is waking up with money in your bag. There’s no better feeling than the ability to enter a store and buy something, when that’s not always been the case. More money means you can be lazier, work less, buy more. Maybe I’m just as simple as the club’s male clientele, in my own way. The costs to work are continually on the rise. When I knew the game, a stage fee was around $80 to $200, plus a house cut on private rooms and payouts to the DJ, house mom, and other managers.

In the last couple years, trend articles on the “death of the strip club” have surfaced. In 2019, the BBC reported that strip clubs across the US were closing because of “changing attitudes, tightening regulations, and a booming porn industry.” This reporting came before COVID, which a Reddit user lamented has changed everything on a thread in r/stripper, titled Are strip clubs dying out compared to a decade ago?

“We ask this every year,” another user replied.

Maybe it’s like the American Dream itself, in a long decline.

“Either she’s a hooker with a heart of gold, she’s a victim, or, at worst, she’s a pro—a hardened hustler who only makes a drag of femininity. All the while, the reality of the situation on the other side of the dressing room door is one full of intertwined motives, dreams, and desires.”

Many of the strip clubs I remember, from when I danced in Times Square, have disappeared. You’d see the names strung along in traffic: New York Dolls, FlashDancers, Lace, Private Eyes. The ads would feature a girl you were supposed to believe worked at the club. Who were those girls, anyway? No one really looked like the ads. Or was it just one girl in various wigs? No matter how the clubs tried to stand out from each other, the nonexistent girl remained eerily similar, as if desire could have only a single form.

There were more clubs, but I can’t remember their names, since they shuttered when the mega-clubs opened more locations. It isn’t surprising that, with zoning laws, and with communities coming after their liquor licenses, less-mega venues have vanished.

There used to be some stripper stores over that way, too. I remember being sent to get a proper thong to dance in (not mesh or lace, by city ordinance) and going around the corner to a shop that specialized in Manhattan club requirements. Long tube “gowns” for weekdays, mini dresses for weekends. What were the other rules? No purses, no drawstring money bags, and no watches, either. Watches reminded the customer of time, of limits, of work—not of fun.

It isn’t wise to wander around with all the cash you’d made on you, but I couldn’t always go home, the club’s gears looping and turning in my body. Besides, Times Square should only be seen at night. Glittering and desolate with no soul in sight, save for the hustlers. There was nothing better to do than wander. Back then, I’d get out at 4 or 5 a.m., still buzzing from the music, and buy something to eat from the halal cart. I’d lie down on the bleachers. At 4 a.m., no one bothered you. You could relax in the middle of it all, and let the hallucinogenic feeling that everyone gets in Times Square wash over you—like it’s the center of the universe, but the universe is only trying to sell you things. Cabs circled, no matter the hour, waiting on whoever needed a ride. Still, I stayed in that moment, not as if time were moving too fast or too slow, but like I was moving with it.