Inside the multiplayer virtual world of furries, glitchy landscapes, and digital slumlords, for Document’s Spring/Summer 2024 issue

AN ENGINE OF ONGOINGNESS

I’m on an outdoor dance floor that doubles as an ice-skating rink; strangers swirl around me while a full moon floats above in an incandescent purple haze. I teleport. I’m on a love island; wild flamingos dot an infinite stretch of ocean, and I crouch behind a tiger to eavesdrop on a proposal. I teleport again. I’m in the abandoned HQ of a property management group called Blackwater; Ukrainian flags decorate a neoclassical palace, strung-out meditation exercises play on loop, the backyard is a galaxy. I pause my e-tourism agenda and zoom out the map. This cluster of sims—the term for an area of virtual land in Second Life—becomes a tiny, twinkling node in an infinite sea of possible worlds.

Second Life, the largest and longest-running virtual world, opened its pixelated doors in 2003 to a global internet audience drunk on the user-driven dreams of Web 2.0. Taking a page from Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi epic Snow Crash, in which users co-build a virtual world that runs seamlessly alongside the real thing, the software’s creator Philip Rosedale cites fond (if hazy) memories of tripping with total strangers at Burning Man as another inspiration. Linden Lab, Rosedale’s company, has adamantly maintained that Second Life is not a game: “There is no manufactured conflict, no set objective,” declared spokesperson Catherine Smith in a 2007 interview.

If it’s not a game, then what is it? Second Life could simultaneously be described as an infinite world engine, a terminally online exquisite corpse, a global economic model, an embodied chat board, and a social experiment. Ultimately, Linden Lab’s position is as much an expansive ideology as it is a branding strategy. The map of Second Life stretches out to overlay the margins of your first one. Unlike its main massively multiplayer online game (MMOG) competitors like VRChat, Fortnite, or Roblox, whose procedural, unsaved worlds are geared more toward letting off steam in drop-in play sessions and, likewise, cater to more mainstream (heteronormative, linear, violent) ways of play, Second Life is always there, remaining online even when the user exits. Its player-made worlds—once preserved on thousands of proprietary whirring servers scattered across the Earth and now hovering dematerialized in Amazon’s cloud—exist forever, waiting for you to log back on.

A 3D GRAPHICS EDITOR DUCT TAPED TO A SOCIAL NETWORK CRAMMED INTO AN ANCIENT REMOTE: THE AGONY AND ECSTASY OF SECOND LIFE UX

In their text “No Fun: The Queer Potential of Video Games that Annoy, Anger, Disappoint, Sadden, and Hurt,” game scholar Bo Ruberg defends “no-fun” games as “sites of queer worldmaking, a call to build alternate spaces both personal and cultural.” Second Life is vehemently no-fun to play, in equal turns boring, frustrating, saddening, and brutal. Linden Lab refuses to regulate the geometric complexity of its users’ creations, known as prims, resulting in hellish frame rates even for the most beastly PC setup. Stumbling through Second Life’s permanently half-loaded worlds is made worse by its clunky interface, which is peppered with confusing, unnecessary controls that reject typical gaming keyboard commands.

All of these issues stack together to form a problematic platform that demands an extremely steep learning curve. And the numbers don’t lie: although it boasts 70 million registered users, Second Life’s daily user headcount in 2023 clocked in at less than 0.3 percent of that figure. Its active user base peaked in 2010, and it’s been in steady decline since 2017, with newer, flashier rivals scooping up much of Second Life’s younger demographic.

“In cultivating an alternative world, we could invent virtually anything— but we don’t stray far from what we already know.”

But paradoxically, the platform’s refusal to submit to the always-be-optimizing logic of other MMOGs is precisely what grants Second Life its enduring appeal among a certain cohort of loyal users. Bucking larger trends of the gaming industry enabled the user experience to evolve in weirder ways, like the player’s ability to dislocate their camera view from their avatar, the platform’s rejection of private property, or the option for players to “feel” any in-world 3D asset to display its entire transaction history, a kind of distributed ledger that presaged blockchain technologies by many years.

Moreover, because there is no boss to beat or competition to win, the vibe on Second Life is ambient, edging closer to the cozy games that ASMR-pilled players in the pandemic. Second Life’s economic and social structures revolve around self-expression through avatar customization and personal world-building, a practice that lends itself well to queer communities and subcultures. “The macho energy you see everywhere in VRChat doesn’t exist here,” user AriesAscending tells me, referring to the popular virtual reality gaming platform that overwhelmingly attracts male-identifying players aged 18–24. AriesAscending and I are talking between sets at TRANSendence, a queer outdoor club set on an idyllic tropical Second Life island. “We got tired of being harassed, so my friends and I hang out here instead. x3”

Despite major upgrades in 2023, Second Life avatars remain obscenely glitchy, with airbrushed faces and spooky, unblinking eyes. Interacting with other players is unbearably awkward. During a dinner date, wine glasses sink into faces and limbs detach mid-conversation, while clothing takes time to load over avatar bodies in user-dense, asset-heavy worlds like nightclubs. There is no centralized mesh system for avatars, meaning your second self can be anything you dream of—so long as you have the requisite Linden Dollars (a blinking animation will run you $49). Paradoxically, Second Life’s hyper-financialization of the human avatar encourages a rejection of the human as the default form of embodiment. I’ve seen griffins knocking back cider in English pub gardens, giantesses roaming the Grand Canyon, and a vorarephilic cake infiltrating a nightclub, handing out forks, begging other users to eat it.

In her text “What Can Play: The Potential of Non-Human Players,” the artist and game scholar Kara Stone argues for a new understanding of the video game as an animate ecosystem. In this framework, the power hierarchy separating player and game dissolves into a kaleidoscopic gamespace built for bacteria, crystals, and plants as much as humans. Musing on how a colony of ants might play as one hive mind, she suggests that “play is a quality that exists between bodies, not necessarily residing in a sole individual.” The latent possibilities of Second Life’s glitchy, weird avatars are likewise clearest in a crowd, where malfunctioning gamespace becomes an interface for posthuman forms of play.

GAMING IS LIFE: THE UNREAL ESTATE OF SECOND LIFE

On Second Life, everyone is either a landlord or renting from one. A modest parcel will set you back around $20 to $40 a month, while a full sim costs $229 to $400 a month. In order to buy land and lease it out, you must effectively become a subsidiary of Linden Labs, paying forward monthly membership fees and HOA dues. It’s tenants all the way down!

When the price of virtual real estate approximates the rent of an actual apartment in some areas, it’s no surprise that some users try their hand at virtual landlordism, an enterprise that intriguingly becomes more lucrative in moments of real-world economic downturn. In the wake of the 2008 recession, amid a surge of Second Life registrations, popular news platforms ran rife with stories of regular Joes quitting their day jobs to become Second Life real estate barons. In the first year of the pandemic, surging demand caused a virtual real estate bottleneck when Linden Labs temporarily ran out of server space before migrating its data to Amazon Cloud storage; e-landlords price-gouged accordingly. And if you couldn’t cough up the Linden Dollars, you were out: In a 2021 episode of the HBO series How To with John Wilson, a Second Life real estate tycoon laments virtual evictions. “My tenants explain like, ‘Oh, my real-life cat had surgery and I can’t pay this month,’” he deadpans. “It can be as traumatic as a real-world eviction, and I really feel for the renters we do this to.”

But despite the exorbitant costs of virtual real estate, don’t expect privacy. Since a user can easily detach the camera from their avatar and gain a god’s-eye view—a practice known colloquially as “camming in”—they can peek into off-limit “drone zones,” typically private homes or virtual brothels, with ease. The Second Life economy hawks solutions, including expensive security drones and ban lines, both of which can temporarily eject nosy users. Another market response is the “skybox”: airborne property parcels positioned thousands of feet up in the sky and camouflaged with a mirror texture. But most players know these largely useless security measures end up being more of a lure than a deterrent. In Second Life, private property becomes a public attraction; tip jars and purchasable offerings litter virtually every sim I tour.

I go for a walk in Los Angeles. Climbing up the winding streets of Mount Washington, which tops out in a sweeping panoramic view of the city’s skyline, I think about the excessive price tag of a skybox up here in the clouds. The hills/flats divide of LA feels like an analog equivalent to the Second Life real estate market: the further above the city, the safer one is from the perceived threat of other residents, a system that reinforces itself through zoning, NIMBYism, and the laws of supply and demand. My mind drifts to Manhattan’s pencil towers and the commodification of airspace in the city, colloquially known as “NYC air rights.” I think about how the same principle applies across both our second and first lives. Real estate, and private property ownership, is the ultimate gamification of space. Whether it’s a skybox or Silverlake ultimately ceases to be the point.

A TIME CAPSULE, NOT A TOMBSTONE

When I get home I log back on to Second Life. It’s a cold and damp evening in LA and I’m craving pixelated warmth; I head to Luskwood, one of the largest and longest-standing worlds dedicated to the platform’s furry community—a subculture interested in anthropomorphic animal characters. Its fairytale forest landscape is cast in perpetual autumn; dying leaves cradle a cozy campfire, which I happily gather round with a few furries. I strike up a conversation with one user, Kyomuno_Tsuki, a pretty fox with long auburn fur, a worn-in leather trench coat, and a gray flat cap that flops adorably over her bright green eyes. She’s either polite or bored enough to indulge some journalistic questions about the semiotics of virtual environments.

“Sometimes it’s a little eerie to think about,” she muses as her fox eyes glimmer, reflecting the light of the fire. Clack clack, goes the clunky keyboard sound effect that signifies a user composing their thoughts. “But there’s places here that people built 18 or 19 years ago that still exist in the same state today. Some of these places are time capsules, probably outliving some of their creators.”

She takes me to her favorite spot in the game, which happens to be in this sim: a gigantic redwood tree, stretching as high as any good skybox. Inside its cavernous undercarriage is a secret shrine to legends of Second Life’s furry community, including the grand architect of Luskwood herself. Photos of various community-builders throughout the years litter the walls. I’m struck by the queer tactic of the archive, to preserve a sliver of the world that the rest is hellbent on razing. “Look for the green dots on the map for real active users,” she proffers, a parting gift of Second Life wisdom. “The bots can’t replicate those, at least not yet.” Heeding her instructions, I head off into the night.

“Perhaps that generosity of opacity— and the generative affect of existing in a world that feels forever out of joint—could offer us the perfect place to respawn, reimagine, and reworld our own.”

I roam Second Life Paris—one of many “real world” locations built by Linden Lab for its users’ digital tourism. I hit an English pub, a strip club inside the Grand Canyon, NASA’s virtual Jet Propulsion Lab outpost, and a seastead real estate office reminiscent of the ribcage-like buildings by the architect Santiago Calatrava.

Scouring the map for homesteads whose names intrigue, I finally settle upon “The Dark Swamp: Home Sweet Home,” owner Ɓʅαƈƙԃɾαɠσɳ (auron29.magic). The portal spits me out underwater. I surface in a boathouse and pan out to a quintessentially Floridian beach home on stilts. The vibe is sweetly Southern, the house a sapphire-tinted clapboard with an ivory wood veranda. Yet, as is often the case with Second Life architecture, the more I poke around, the weirder things get. Its interior, a postmodern pastiche recalling the wholesale offerings of the real-world furniture store chain Rooms To Go, is spiced up with carved sigils. Outside, gigantic sculptures of dragons and roaming charismatic megafauna litter the swampy garden. I grab onto various prims; the last recorded asset modification was in 2017, indicating an abandoned sim. Eventually a wolf approaches me, emitting a pitiful wail that makes me think of the island’s owner. Where is Ɓʅαƈƙԃɾαɠσɳ now? Do they ever think about the world they left behind?

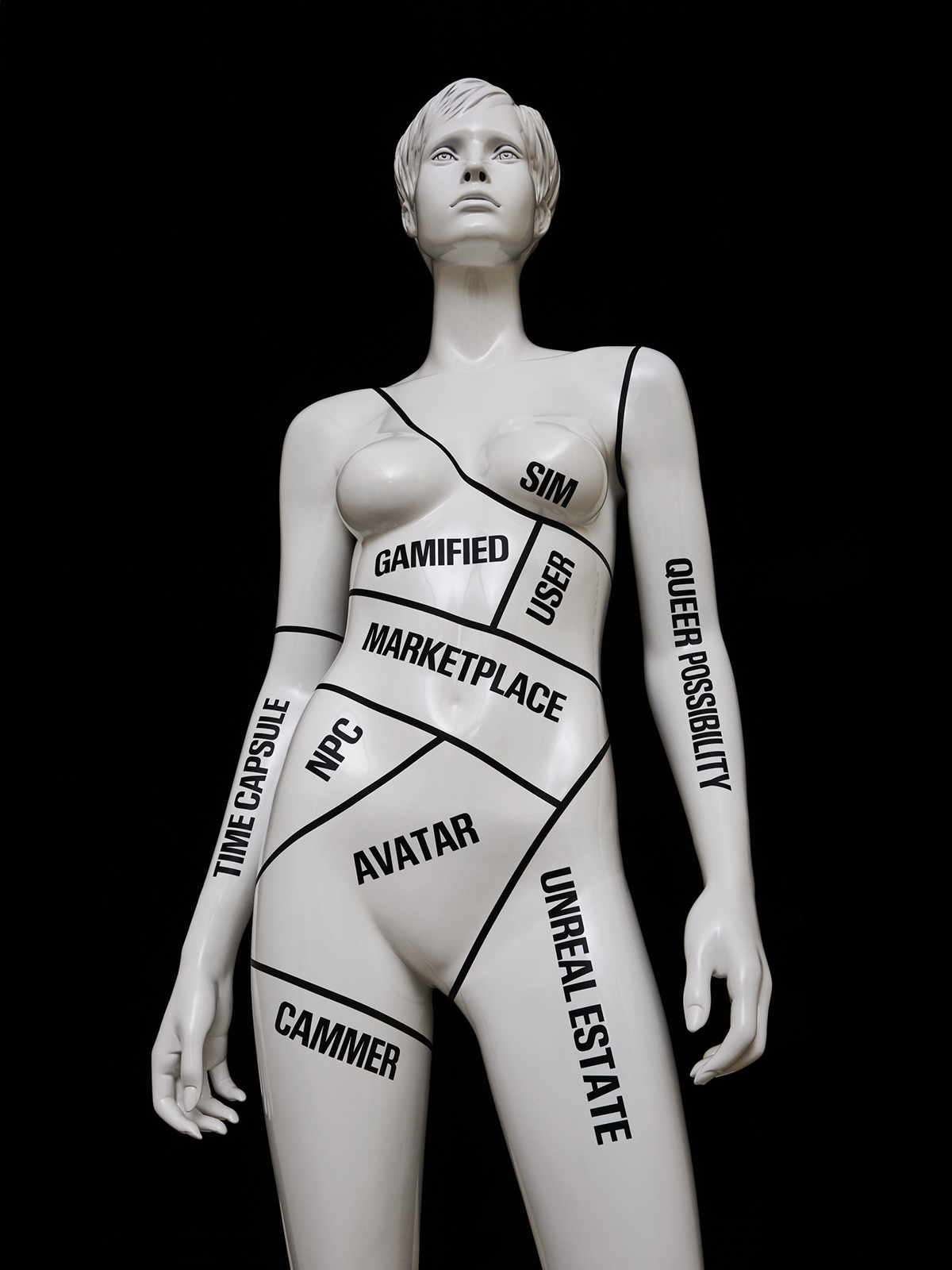

THE QUEER GAMIFICATION OF VIRTUAL WORLDS

When drawing comparisons between Second Life’s economic imperatives—avatars and property—it’s tempting to cite gamification principles: a marketing catchphrase popularized in the 2010s that suggests applying game design principles to products and services in order to boost revenue. But as theorist Ian Bogost has pointed out, gamification overemphasizes video games’ most boring element—game theory—at the expense of all the other delightfully freaky ecosystems that these virtual worlds and their players induce. I would go one step further, arguing that even the “gamification” of players who invest in a platform like Second Life is inherently queer. Dropping up to $1,000 on a virtual property box in the sky or a perfectly kitted out furry avatar is a blatant rejection of the heteronormative superstructures that dictate who or what we should spend money and time on in “real life”: kids, rent, friends, or partners.

But for all the ways that Second Life queers notions of embodiment and private property, there’s a tragedy baked into its architecture. In cultivating an alternative world, we could invent virtually anything, but we don’t stray far from what we already know. Rambling across the near-infinite roster of Second Life sims, a deep melancholia sets in, catalyzed by the realization of just how reality-adjacent it is to First Life. This is a truism leveraged more broadly against the platform’s system architect, Linden Lab, than its users, who seem to delight in moments when that system breaks down, from avatars to property, scaffolding new social behaviors atop its fault lines.

“The whole of life appears as a vast accumulation of commodities and spectacles, of things wrapped in images and images sold as things,” McKenzie Wark remarks of First Life in her book Gamer Theory. But when the whole world is Game, and the Game is World, where do we go?

Perhaps as the software of Second Life continues to age and degrade, more pockets of resistance will form. Perhaps the platform may, ironically, feel more utopian, more like our own to choose, as First Life slides into an increasingly ghoulish metaverse and we reach peak “NPC syndrome,” overwhelmed with the sensation of being trapped inside a game where we don’t know the rules. The ambient indeterminacy of Second Life is always what made it a place worth preserving. Perhaps that generosity of opacity—and the generative affect of existing in a world that feels forever out of joint—could offer us the perfect place to respawn, reimagine, and reworld our own.