‘Masculinites: Liberation through Photography’ spotlights Catherine Opie, Peter Hujar, Wolfgang Tillmans, among others.

They say gender exists on a binary, but they are misinformed. Masculinity and femininity are not ends of a pole, but two parts of an ever-expanding circle, constantly seeking new expression in the world. We’ve been indoctrinated to see binaries where they do not exist, buying into simplistic “either/or” constructs that create false hierarchies and real inequality.

“We live in a moment where, on one hand, we’ve never lived in a more tolerant and inclusive society and on the other hand it feels incredibly homophobic, transphobic, and women’s rights are being eroded,” says Alona Pardo, curator of the new exhibition, Masculinities: Liberation through Photography. Although Pardo first conceived of the show years ago, the #MeToo movement galvanized her thinking about hegemonic masculinity in the West where, in recent years, we have been experiencing a relentless resurgence of regressive leadership.

“This is a pivotal moment,” Pardo says. “We talk about toxic masculinity, fragile masculinity, and the crisis of masculinity—and there certainly is. This hegemonic masculinity that defines the dominant, white-fisted male in Europe and North America has very outdated codes to which they subscribe: physically aggressive, combative, physical size and strength, stoic, and resilient. These tenets of masculinity are designated as static and immutable, but when you begin to unravel this thing, its foundations are precarious.”

The modern concept of masculinity first took root in the Industrial Revolution, when the agrarian world first began to fade away and men made their way to the cities to work in factories. “Before that we had these very Rococo dandies that were very flamboyant in how they dressed, shared great passions with each other, had more tactile relationships, and expressed themselves more,” Pardo says. “There was a different gender division. Men were more aligned with the earth. They worked the land with their children and were much more a part of the home. They had a different relationship to family.”

With the radical, rapid change from the natural to the manmade world, the patriarchy introduced new archetypes of masculinity based on cis heterosexual tropes: the soldier, the cowboy, the cop, the factory worker, the athlete—figures that flourished in what had been exclusively male realms that used strength, weapons, and machinery to establish dominance. The media, entertainment, and information industries lionized them as paragons of masculinity, placing them at the top of a specious hierarchy and subjugating all other expressions of gender as lesser, if not outright criminal.

“In order to maintain the patriarchy and their positions of power, they need to maintain the status quo. Anything that is a potential threat makes them hold on evermore to these very outdated codes of masculinity,” Pardo says. “There are all sorts of structures in place that help them secure these ideas of manhood, but it’s a complete social construct. As a result, they don’t live up to these ideals. Any kind of gender is a performance. It’s all artifice and hard work. Ultimately, it’s upheld by a fear of collapse. It’s about power.”

As hegemonic masculinity asserts itself, it is met with pushback from all who do not identify with its restrictive, oppressive codes. Centering on those who have long been marginalized, if not wholly erased, lies at the very heart of Masculinities, which asserts a glorious spectrum of male-identified existences from the 1960s through today. The exhibition examines themes like power and patriarchy, hypermasculine stereotypes, fatherhood and family, Blackness, queer identity, and female perceptions of men in more than 300 works from over 50 photographers and filmmakers including Richard Avedon, Kenneth Anger, Samuel Fosso, Isaac Julien, Deana Lawson, Ana Mendieta, Robert Mapplethorpe, Catherine Opie, Peter Hujar, Wolfgang Tillmans, David Wojnarowicz, and Andy Warhol.

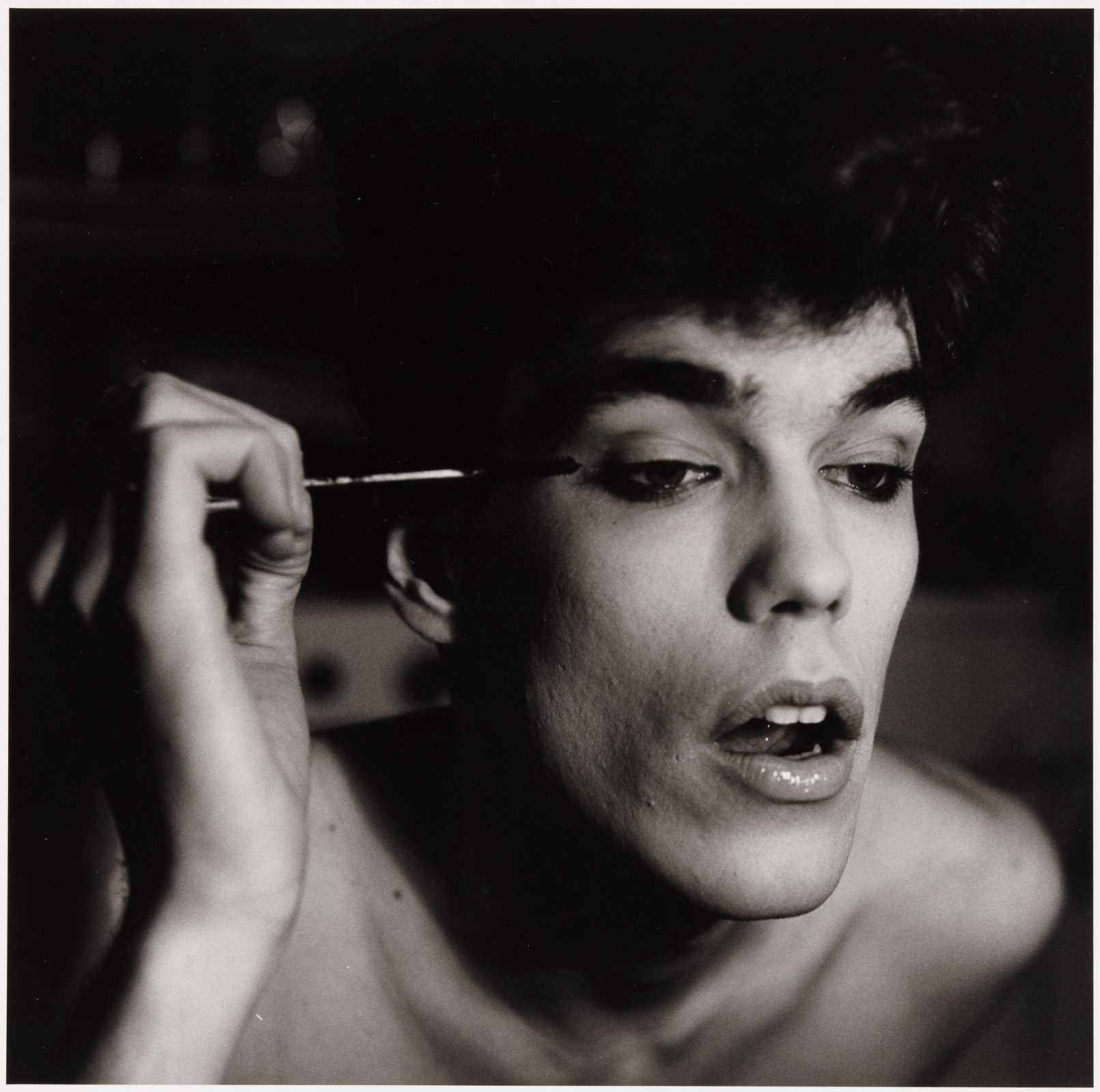

With Masculinities, Pardo deftly draws a parallel between the constructs of gender and photography. “The great thing about the camera is you perform for it. Photography is based in the real world and is a reflection of acts taking place,” Pardo says. “The works in the show are deliberately performative. We are showing little documentary work. These are artists who have art directed, staged, or collaborated with their subjects to take these photographs. The exhibition is also looking at the limitations of photography and questioning it as a medium.”

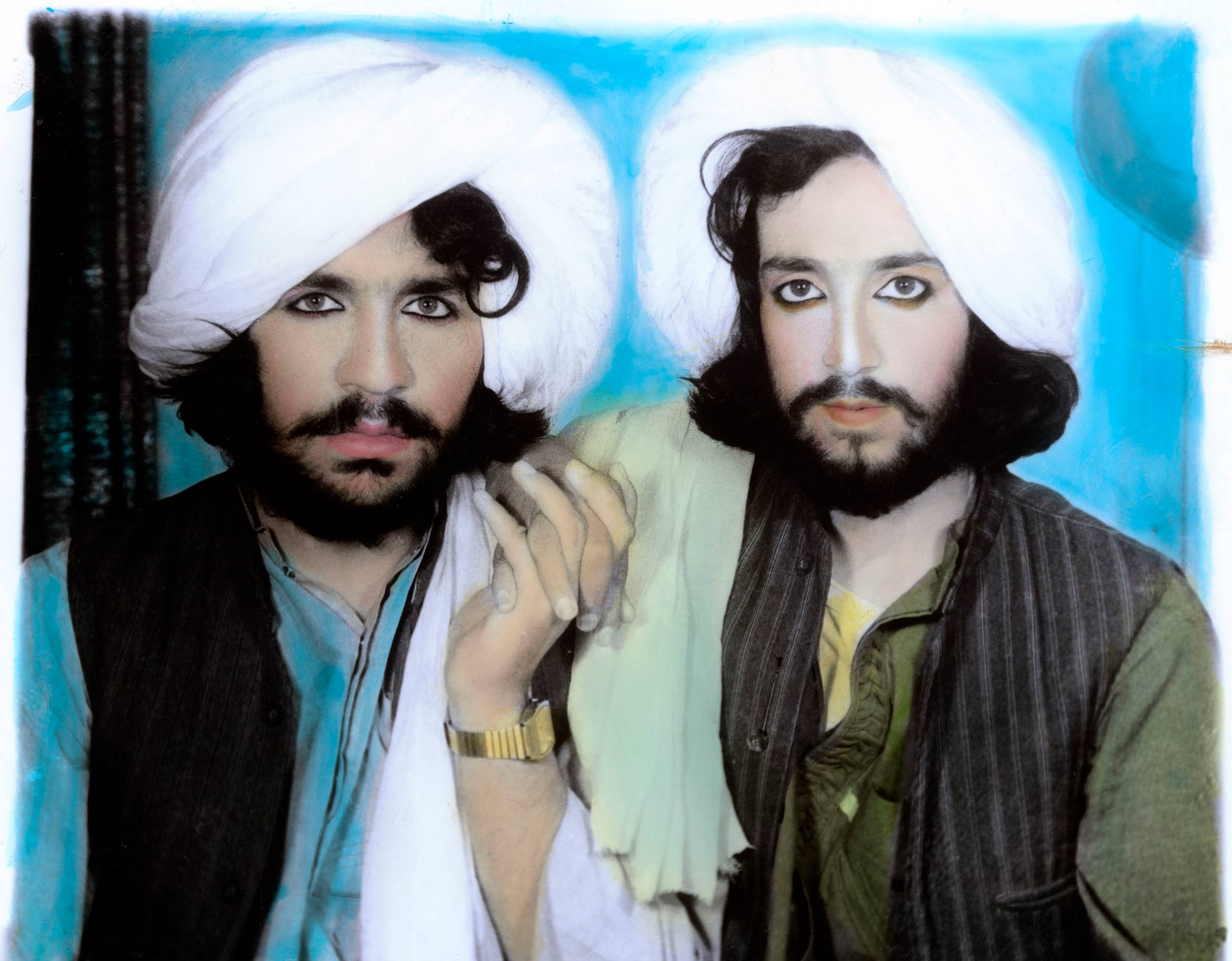

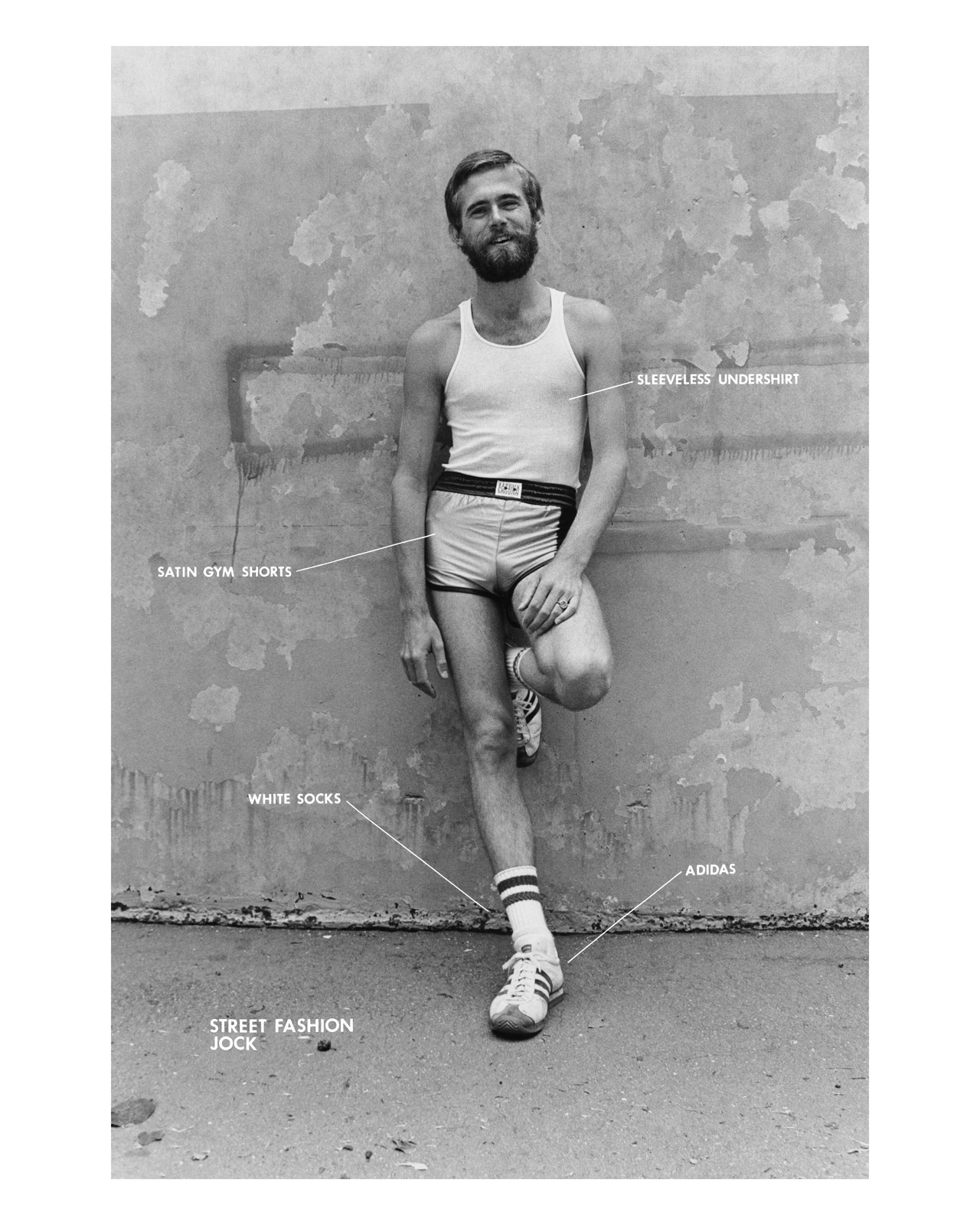

The photographs featured in Masculinities are delightfully subversive works. Here, the beauty of men is presented as an extension of their soul, whether in George Dureau’s exquisite portraits of amputees or John Coplans’s monumental nude self-portraits made in his 70s. We see portraits of Taliban members as they saw themselves, in glamorous hand-colored studio portraits they made despite the laws they issued banning photography. Hal Fischer shares work from his landmark series, Gay Semiotics, made in San Francisco in the 1970s, which reveals insider knowledge of how men communicated their desire through dress with items such as a blue handkerchief placed in the right hip pocket that“serves notice that the wearer desires to play the passive role during sexual intercourse.”

Visibility, representation, diversity, and inclusivity have become the buzzwords of our age, used for both “good PR” and genuine efforts to create change. Masculinities does what few museum exhibitions have done before—it brings together those who have been pushed to the periphery for a kaleidoscopic, unfettered look at manhood by engaging with these principles on multiple levels.

“We need positive representation of all these typologies of people, for it to be normalized,” Pardo says. “In order to come out of the margins and enter the mainstream, you need to be seen. The great thing about photography is that it pictures them and can be reproduced, circulated and disseminated all over the world, now no longer just through printed media but on the internet. It’s important for photographers to keep documenting, making and publishing these images and showing us different ways of being. That’s how we can become a more accepting and appreciative society of others.”

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is on view at the Barbican Art Gallery in London from February 20–May 17, 2020. A book of the same name is published by Prestel.