Featuring contributions from artists, scientists, and philosophers, Aperture magazine’s Winter 2019 issue calls for a new model of spirituality that champions solidarity over self-betterment.

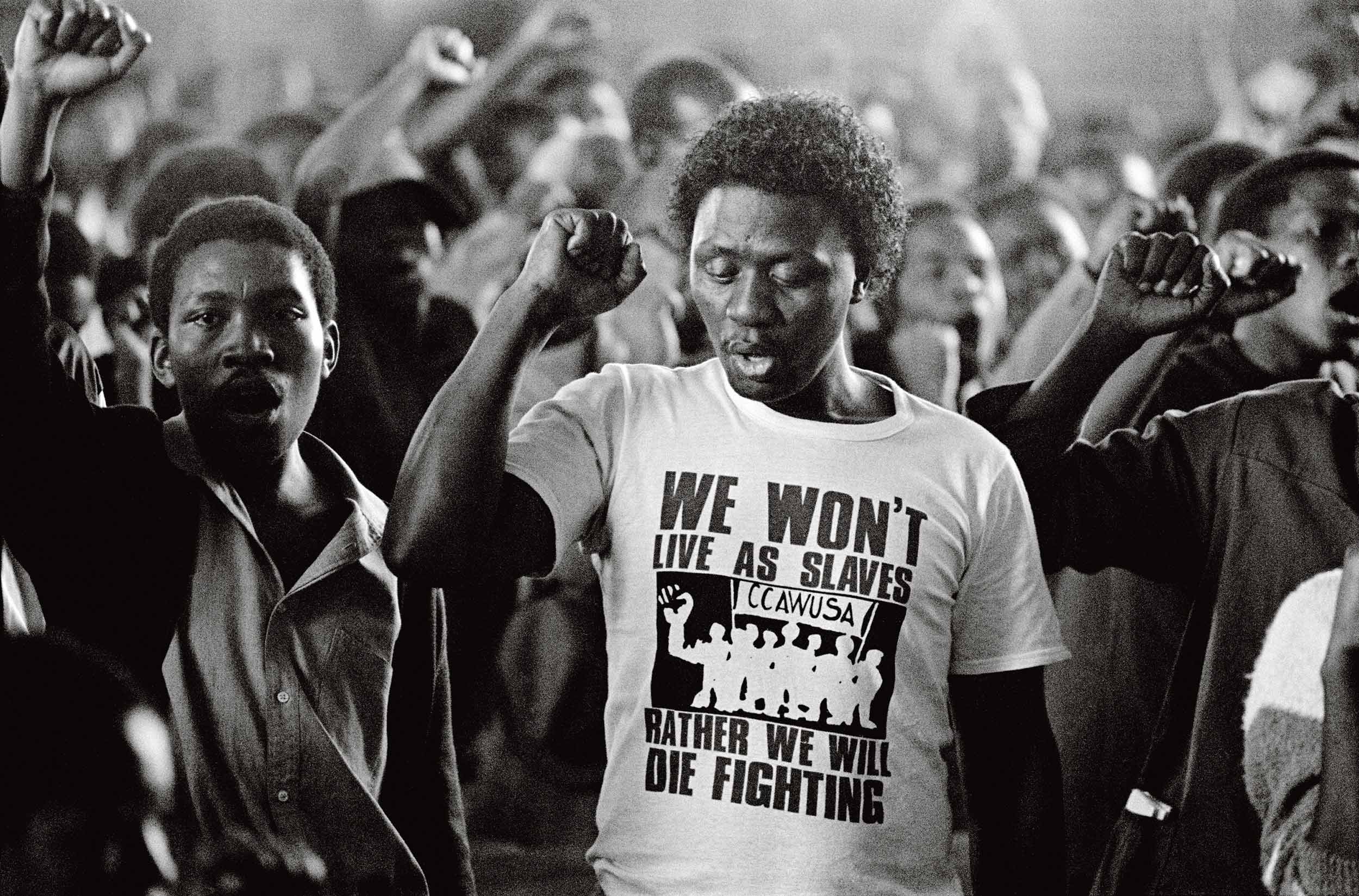

As guest editor of Aperture magazine’s Winter 2019 edition, Wolfgang Tillmans examines the relationship between spirituality and solidarity. Known for his intimate documentation of sub-cultures and communal experience, Tillmans casts the same perceptive gaze towards the broader spiritual condition in order to better understand humanity’s persistent longing for universal connection. Featuring contributions from artists, scientists, and philosophers, the issue tackles questions of faith, freedom, and social responsibility. Key features include To See the Unseeable, a conversation between author Elizabeth Kessler and physicist Peter Galison about his work producing the awe-inspiring first image of a black hole; David Swindells’s chronicle of underground rave culture; Siddhartha Mitter on the collective solidarity of protests in Hong Kong, Cairo, and Standing Rock; Sean O’Toole on Santu Mofokeng and South Africa’s spiritual landscapes; alongside portfolios by Susan Hiller, Mare Nero, Harit Srikhao, and more.

In conversation with Wolfgang Tillmans, philosopher Martin Hägglund advocates for a more community-oriented ethos, probing at the geopolitical factors that gave rise to the current model of what he deems “self-optimizing spirituality.” “People tend to think of spiritual fulfillment in terms of turning away from our interdependence—precisely because that interdependence is so constraining and painful under capitalism.” In a culture that increasingly values the individual as a commodity, Tillmans and Hägglund call for a new model of spirituality that champions collective action over individual introspection.

Similarly, David Campany references the work of Ronald Purser, who argues that certain models of spiritual practice have come to function as a coping mechanism for the existential stress of modern life—namely, the dearth of meaning produced by life under consumerism. Framing meditation and mindfulness as a personal journey of self-betterment individualizes our responsibility for our own spiritual well-being and precludes spirituality’s greater power: to foster greater awareness, connection, and a relationship with something bigger than the self.

With subjects ranging from solidarity on the London dance floor to protests as a form of communion to celestial objects 55 million light years away, the issue leaves little doubt that spirituality can be found in unexpected spaces, places, and moments. “If you can see the world in a grain of sand, then the spiritual is everywhere. No place, image, artist or lifestyle guru has any privileged access to it,” David Campany reflects in his essay on photography’s attempts to represent transcendence. “[It’s] not something you can be instructed to feel… The spiritual is a condition of response, not a type of picture.”