April Walker, Angela Boatwright, and Vicki Tobak detail the explosive evolution—from Salt-N-Pepa to Nicki Minaj.

More than 45 years after hip hop got its start in the Bronx, a new wave of women are dominating the charts and challenging the hypermasculine culture by embracing their agency. Artists like Cardi B, Nicki Minaj, Megan Thee Stallion, City Girls, Rico Nasty, and Doja Cat are changing the game with their fearless style, bold personas, and lyrical flow—transforming their fierce, feminine energies into cold hard sales.

Though there have always been women in hip hop, it was, and largely remains, a boys club. But the success of female artists represents a significant shift in the culture, revealing there are fewer limitations for women than ever before. “Nowadays, women are more empowered. They can move through the world and operate however they want,” says Vikki Tobak, curator of Contact High: A Visual History of Hip Hop, a new exhibition and book that features iconic works by women photographers including Janette Beckman, Angela Boatwright, Martha Cooper, Adama Delphine Fawundu, Sue Kwon, and Sheila Pree Bright, among others.

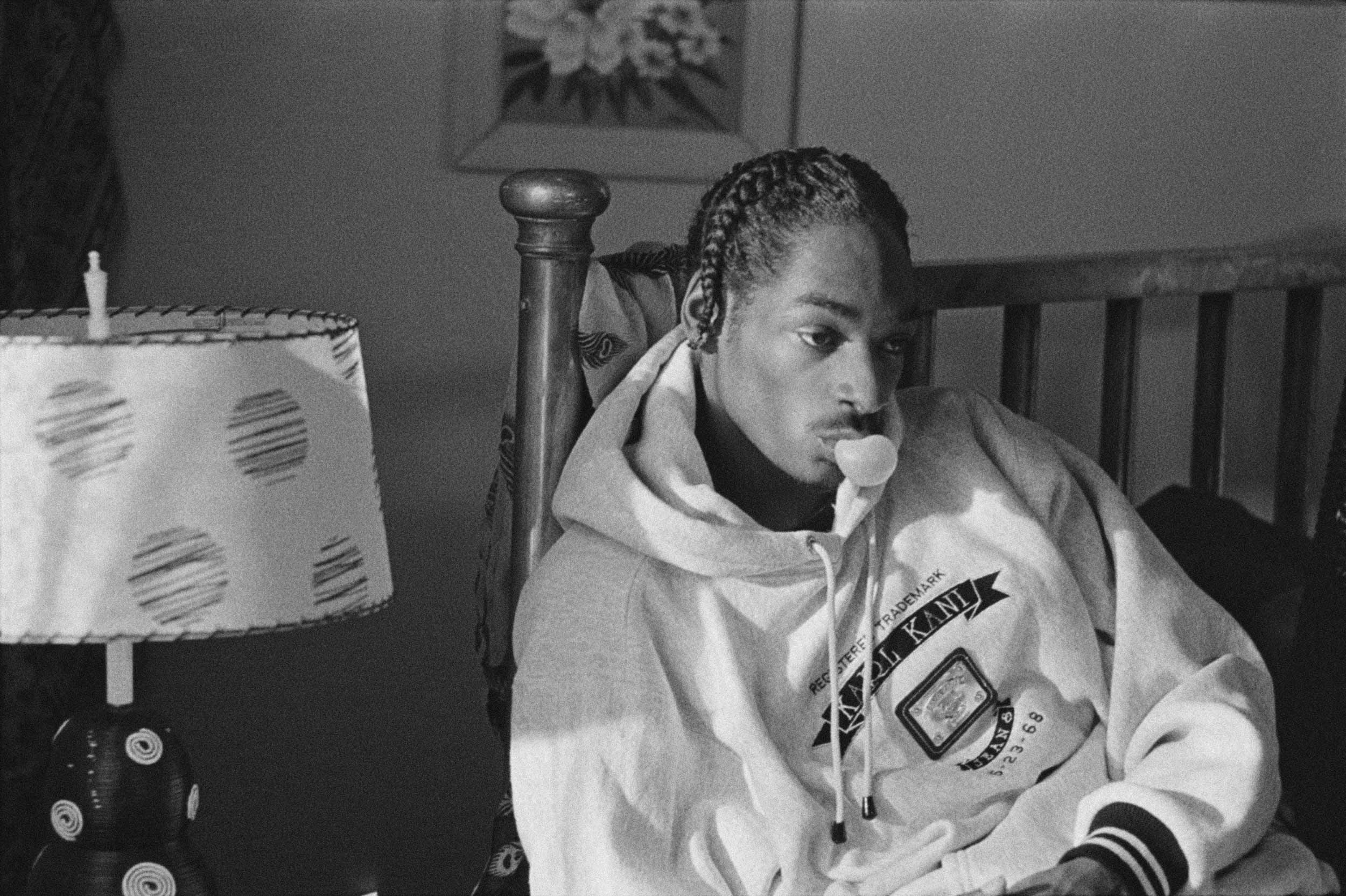

Contact High showcases the contributions of women on all fronts, whether in front or behind the camera, styling the shoots or designing the clothes. “I saw myself as the Lone Ranger in my lane,” says trailblazing entrepreneur April Walker, the mastermind behind the iconic ’90s apparel line Walker Wear, worn by celebrities including The Notorious B.I.G., Aaliyah, Tupac Shakur, Run-DMC, and Snoop Dogg. “I remember deciding that I was not going to let the world know that there was a woman behind a men’s brand. It was really unheard of at that time. Instead, I let the product speak for itself and get out there before I started doing interviews. Looking at the trajectory of hip hop, women have had to fight tooth and nail in every space that we existed.”

Today we stand on the shoulders of giants and pioneers, women whose love of the culture inspired them to create, innovate, and contribute. Here, Tobak, Walker, and Boatwright share their memories of being a woman in hip hop during its formative years.

April Walker: There were so many first moments for me. There was a whole culture of bringing turntables outside to play in the park. We’d go and listen to this music that no one understood but we felt like we were all the same tribe and doing something so cool. The music united us. Then, as an early teenager, there were house parties in the basement with strobe lights where you would be with your friends listening to the Sugarhill Gang, and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. By this time I was fully immersed in it—this is my life.

Angela Boatwright: April is at the epicenter of hip hop. If you put a drop in the lake and it recedes outward, I’m on the outer periphery. I was 8 years old in 1983, so for me, hip hop was rollerskating. Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back [1988] became a huge hit for me because I was a heavy metal girl. It was angry, thought-provoking, and aggressive. It changed your mind. It fed you information—it wasn’t just entertainment. Public Enemy turned hip hop into something I would focus on more consciously when I moved to New York.

Vikki Tobak: In the late ’70s, we moved to this country from Kazakhstan and we landed in Detroit. Growing up, I felt like an outsider to everything except music. I would hear on the radio: Motown, funk, soul, Prince, and early techno music—it looked and felt like the city felt to me. Music made me understand where I was and provided a lot of answers. When hip hop came out of New York with Public Enemy—that was what I was seeing in Detroit. It was like: you don’t need validation from mainstream America that, as an immigrant kid, I never felt I was part of. Hip hop made that okay.

April: Hip hop was the voice for the voiceless. It was the expression of what was going on in every hood, not just in New York. It was our way of telling the world what we felt. My father was in the music business at the time managing jazz. When Guru moved in my building, I gave him Guru’s first demo. I was like, ‘You should listen to this. It’s coming.’ I was always in the clubs, watching the way we were starting to express ourselves, manipulate our clothing, and remix it. We were blinging it out, airbrushing, acrylic painting it, bleaching it—all these things to match the vibe of how we felt. I started making clothes when I was a junior in college. I had no clue what I was doing but I felt it inside. In 1988, at the age of 21, I opened Fashion In Effect, my first custom shop in Brooklyn on Greene Avenue in Clinton Hill. We had a homemade sign. Everything was makeshift. When you walked in you tagged the wall. It became the wall of fame for breakdancers, graffiti artists, airbrush artists, hustlers, rap artists, It was word of mouth. One person at a time started feeling the energy and passing it on. Dapper Dan was a mentor in my head at that time. I didn’t know him but I went to his spot one night and that was my awakening, like, ‘I can create a business.’ We started with original designs, which gave us the gumption to say, ‘Let’s do our own line!’ That’s when I started Walker Wear.

Angela: I made my way to New York when I was 18 in 1993. It was not the easiest thing but I dug my heels in and went to school for photography. I remember driving to New York and seeing graffiti on the freeway in mid-Jersey. It always made me feel like I was at home. Graffiti pulled me in. I started working for Mass Appeal magazine in 1996. I realized you don’t need to rent a studio in New York; there are backdrops everywhere. In the ’90s, artists really enjoyed being photographed in the streets. Hip hop artists were always rock stars. They brought it—everything about their being, their energy, the commanded an audience. They knew who they were.

Vikki: In high school, I wanted to move to New York and be a part of hip hop. I got into NYU. At night, I was working at Nell’s, a nightclub that was a big hangout for hip hop. I met Patrick Moxie, Gang Starr’s manager, who was starting up Payday Records and started working there. When I came into hip hop in the early ‘90s, it was a relatively small community. I was seeing a lot of behind-the-scenes women in powerful positions: women that were running labels, that were head of marketing at labels, powerful women editors at hip hop magazines like Danyel Smith and Mimi Valdes at Vibe and Sheena Lester at XXL, and all the photographers, Janette Beckman, Delphine Fawundu, Angela—they were always there.

April: From the beginning, I had the spirit of a hustler so I came in with a different lens. I saw early on the difference between men and women. It was a microcosm for what existed in America, period. It still exists. We’ve really improved but we look at dollars—what a man is getting and what a woman is getting–and we still have work to do. Back in the ’80s, it was a lot worse. Being a woman, and a woman of color, on top of that? It was like, ‘Are you nuts? You passed the city jobs. You could become a Firefighter, a Corrections Officer.’ Those were safe jobs my mom wanted me to do. But I was following my dream.

I remember seeing a shift happen one by one, first with Lyte then Salt-N-Pepa, who produced the album Blacks’ Magic [1990]. They were defining for my career in terms of being sexy, powerful, empowering to other women, and independent. They not only learned the business, they separated from idol makers to do their own thing. On the back end, I agree with Vikki, we did have women but there was still a lot of work to do on the pay scales and the bounce back rate; it was easier for men to move around than it was for women. As women in the industry, we had to work hard to keep a clean reputation whereas men didn’t have that problem. Men could sleep with 100 women and still get their money and move up the ladder. As women in the ’80s and early ’90s, we had to be fly, smart, and be respected. I think it was a lot harder to be taken seriously if you were perceived as a woman who was sexually liberated.

Angela: I’m a psychology student these days and there is something called ‘The Cool Girl Trope’: a girl or woman in a male-dominated scene who lets the guys do whatever they want. She doesn’t necessarily sleep with anybody but they guys consider her available. Speaking for myself, you fall into the cool girl role. As a woman, you want to be treated like the men treat each other and to be included in that power. My naïveté left me open to be treated very poorly but it also got my foot in the door because I was following my gut. It allowed me to slide through all the manufactured barriers. What I love about Contact High is that it could have been an all-male photographer show and any curator would have away with it.

Vikki: People often assume the person behind it is a man.

Angela: It never ceases to amaze me how many women have gotten shine because of your work. The exhibition places us in history, which is so important. You provided a home for us.

Contact High: A Visual History of Hip Hop is now on view at the International Center of Photography in New York through May 18, 2020.