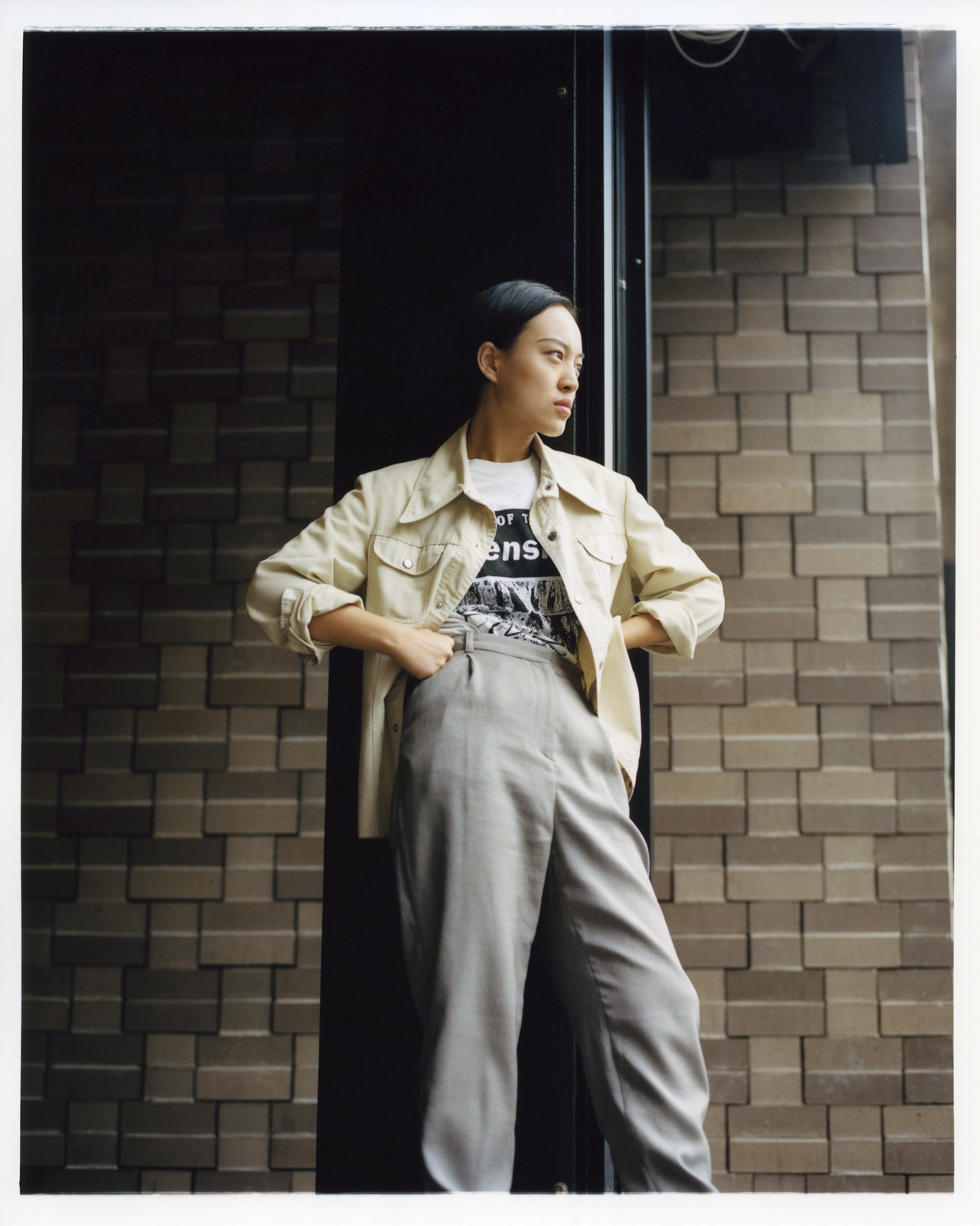

Ahead of 'Tissues,' a new play performed by an ensemble of 13 opera singers and performers, the experimental sound artist discusses her obsession with dualities.

“For me, ‘opera’ is a very big word,” says the artist Pan Daijing as she sips her coffee at Tate Modern in London. “You can think about it as a specific music tradition, or a political standpoint, because of its history. But for me, it’s about composition.” On the cusp of her 28th birthday, the China-born, Berlin-based artist is about to start rehearsals for her latest creation, Tissues—her fourth operatic incarnation. “It’s music composed for opera singers,” she explains. “Wagner talked about opera as a philosophical term because of how it combines drama and narrative. To be honest, it’s much easier—more natural and organic—for me to compose this way. Because I think my nature is storytelling; experimental storytelling.”

As an entirely self-taught electronic artist, Dajing is known for her avant-garde sound. She draws upon a wide repertoire of improv, performance, installation, and sonic art to create something entirely unfamiliar. The eclectic roster of places she’s performed at gives you a good idea of her non-discriminatory sensibilities: London Contemporary Music Festival, Palais de Tokyo, as well as Sonar, Unsound, and Berghain.

Tissues is about Daijing’s obsession with duality. It’s based on an old Chinese film about a girl with dual characters; one identifies as a woman and the other a man. Constantly trying to obliterate each side of her personality, the woman becomes skilled in the art of killing, but soon realizes that a life set upon destruction is a one-way road to loneliness, and she ultimately ends up in solitude. Daijing says the story appeals to her fascination with multifaceted stories; night and day, dark and light: “Of course, it has a lot of my own personal interpretation.”

Daijing’s work is cinematic and moody. Often labelled noise music, it’s as atmospheric as it’s uncanny. Tracks overlaid with operatic vocals and the sound of oscillating radio waves mimic industrial soundscapes. Filled with expanses of repetitiveness, they pummel you into a stupor. It’s this trance-like quality that’s become a hallmark of Daijing’s sound, which, she tells me, goes back to her childhood in China: “Every society has its own uniqueness, I just happened to be in one that looks very different than the others. You kind of have to constantly be in the trance to be able to survive it.”

Born and raised in Guiyang, in the South-West of China, Daijing was taught about the extremes of human emotions: “Growing up in China is why I’m so interested in people, because my youth was so unhumanized. When you are in a country of that many people, you mean nothing because we already have so many.”

At 17 she moved to Beijing to study, and it’s during this time when she had to take the gaokao (a mandatory two-day test for Chinese students who want to pursue higher education) that she learned first-hand about being pushed to her limits. “I think [the gaokao] is very traumatizing for someone that young. But that kind of intensity and darkness, and that really brutal way of treating people, and how it affects them, has really inspired my work.”

That fascination with the playing out of human emotions can be seen throughout her work. “My opera has acts in a traditional sense but the interpretation changes depending on who I work with,” she says of her process. “No matter who you work with—singers, or actors, or dancers—everybody has their own instrument, or their most powerful tool of expression,” she explains. “Every single person in the cast really understands music as a way of communication. It goes beyond words.”

Tissues will be performed by three opera singers and 10 performers. With a cast that big I ask her how she takes everyone’s input on board: “I always take time to get comfortable with the performers first and make them feel like there’s no judgment,” she says. “They don’t have obligation to perform or to impress me.”

It’s a very humble way to create a type of music associated with prestige and ego. I ask Daijing why she goes out of her way to make it a collaborative process. “I just really, really adore music,” she answers. “Music, for me, is a very ultimate form of expression. And it shouldn’t just be aligned to entertainment or be so protected or so exclusive.”

It’s that ability to turn away from how opera and classical music is expected to be that makes Daijing boundary-defying, but not everything can be traced back to her heritage. “I think I have a lot of courage in my work,” she adds. “I’ve never studied a single day of music and now I want to write an opera. Where does that come from?”