William Eggleston is credited with ushering in the age of color photography and becoming the first photographer to make color his main medium. Eggleston’s daughter recounts their relationship and details her inspirations for Document's Fall/Winter 2013 issue.

I drove up from New Orleans to meet Andra Eggleston in her father’s new apartment in a renovated 1920s hotel in Memphis. I’d first met Andra as a toddler shortly after her father took the art world by storm in 1976 with his solo show of color photography at the MoMA, but I hadn’t seen her since she’d returned to the South and Nashville to work on her design business with her husband, Emery Dobyns, a music producer and songwriter and their 3-year old son, Louis. When I heard that she and her dad had recently been collaborating on an art project, I was immediately intrigued and asked her if she would be willing to talk to me about it.

Everett McCourt—Tell me about your textile collaboration with your father—how it started and how and when it developed.

Andra Eggleston—I love to think about the inception of my relationship with my father surrounding textiles. As a child, I had a natural affinity for drawing. And much like my father, I would use anything around me to draw on. I used to draw and discard, draw and discard. The next day, or the next week perhaps, I would find my discarded drawings hanging on the walls like art. So it was unspoken between us, but I knew and appreciated how he felt about my drawings. This was the greatest encouragement I ever got from my dad. And that was how I discovered his love for textiles, too, through his quiet love for mine.

Everett—How did you get started as an adult sharing your father’s love for abstract drawings?

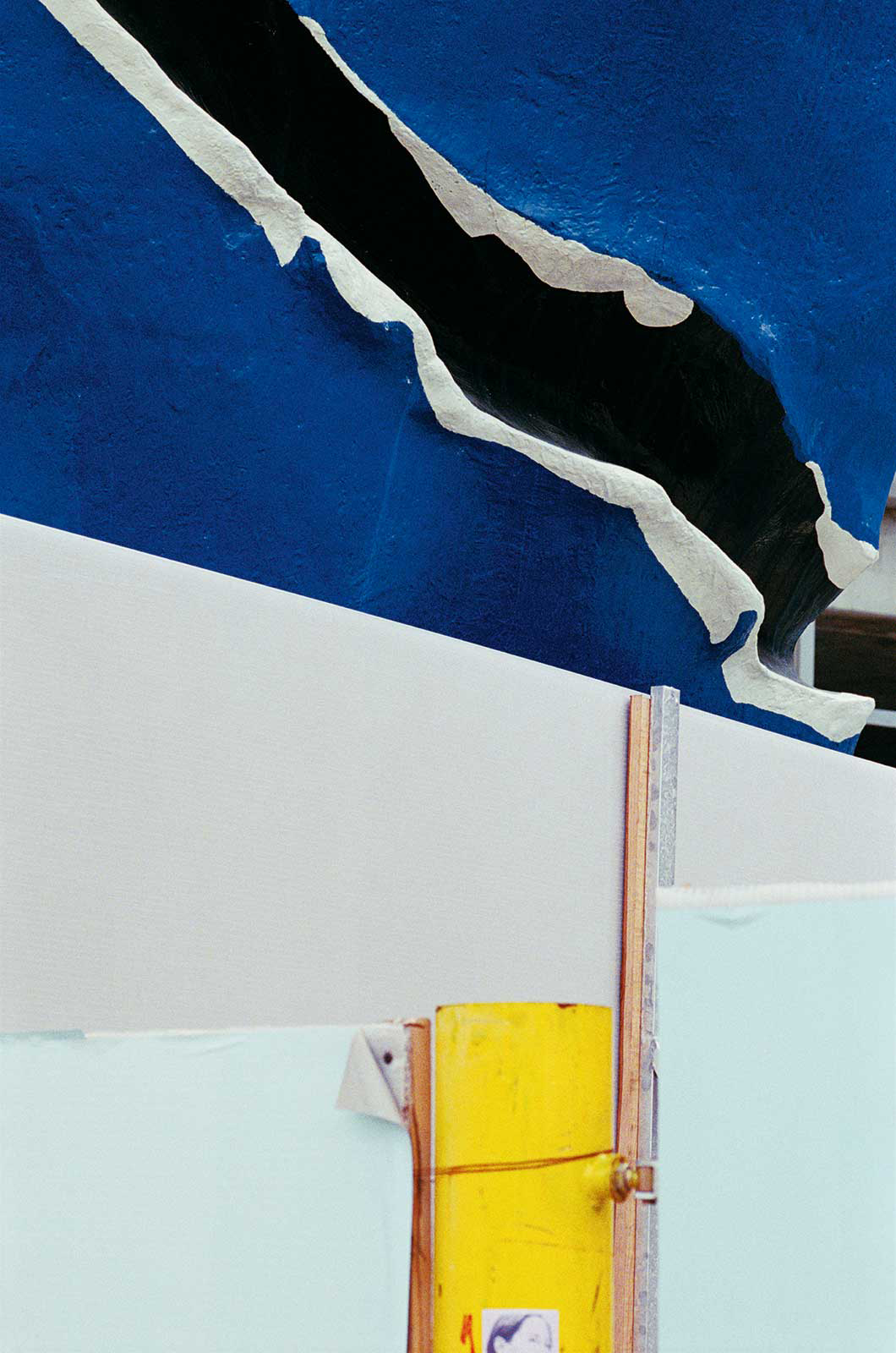

Andra—I recently moved to Nashville after having lived on East and West Coasts for 15 years. I decided one day to drive over and see if I could encourage him to make one of his abstract drawings for me. I had always been drawn to his abstracts. The first visit was extraordinary. He painted nothing! But I began to paint. And we would sit together, look at his drawings, his photos, listen to Bach or to music he had written, play a David Lynch movie in the background, smoke cigarettes, eat fish eggs. It was the most natural and peaceful I may ever have felt with him.

Everett—Textiles can be more fluid or continuous and can even shape-shift—as clothing, for example. Are you playing with or considering these differences?

Andra—I agree. For this reason, they can take on unique and various personalities. For example, the same print could be on a sheer piece of lingerie as well as a thick curtain made of hemp. I have made some extraordinary friends here in Nashville who have helped me come to the realization that textiles in particular need to be left to the designer. In other words, what I am striving to do is to let the work speak for itself. I would like to approach other designers in fashion, furnishing, or housewares, for example, and let them be inspired by the designs and use them as they see fit.

Everett—Both textiles and photography have an inherent print aspect. How does that fit into your collaboration?

Andra—This is so much like my dad’s photography, as you know. His works are untitled and he usually responds with “no comment” when asked for meaning. I really want other designers to find that meaning for themselves. I think there is freedom in that.

“As a child, I had a natural affinity for drawing. And much like my father, I would use anything around me to draw on.”

Everett—Your father is an accomplished pianist and composer as well as visual artist. Does music inform and influence your creative process as it does his?

Andra—His musical tastes are so ironic. When I was little, he used to play a reel-to-reel of the Chipmunks’s Christmas year round, at any hour paired with lots of Bach cathedral organ music. And this is still the case — today it’s Japanese pop from the ’80s and ’90s paired with Beethoven and Bach.

Everett—Have you used any of his actual abstract patterns in your textiles? If so, would he be credited? I wonder how this would increase the market value of the item it was used in?

Andra—Together we have been editing down a selection of his drawings that could be appealing as textiles [hardly any have been recorded into the Eggleston archive database, and none have been scanned until now]. Then I am taking those images and playing with different textile arrangements. From there we decide if they are viable or not. Every one we do is making my eye and my instincts sharper. I love having my dad around because he very often shows me a completely different way of looking at something.

Our abstract styles are very different, and at first I thought that even as a collaboration it wouldn’t work. But now, they are so intertwined. I think they are complementing each other amazingly well. And that is the brand we are building.

This article originally appeared in Document’s Fall/Winter 2013 issue.