From scorched valleys to shadowed interiors, Caleb Hahne Quintana’s latest exhibition at Anat Ebgi unravels a myth on canvas

Caleb Hahne Quintana paints in the sun-bleached palette of his native Colorado. From afar, his canvases seem effortless in their clarity; up close, layers of paint blur into hundreds of subtle shades that resolve into a single limb or a patch of sky. His latest series, A Boy That Don’t Bleed, on view at Anat Ebgi through October 18, 2025, pushes this concern with paint into new psychic terrain.

Most of Hahne Quintana’s paintings start as drawings on white paper. Last year, he bought a block of black paper by mistake. “I decided to use it,” he recalls, “and discovered a completely new way of seeing color.” What followed were months of experiments until his sketches no longer faded into the darker ground but hovered and pulsed as if lit from within. While many of the works here mark this turn, some take on the hazy fields of orange, yellow, and green that have long anchored his work.

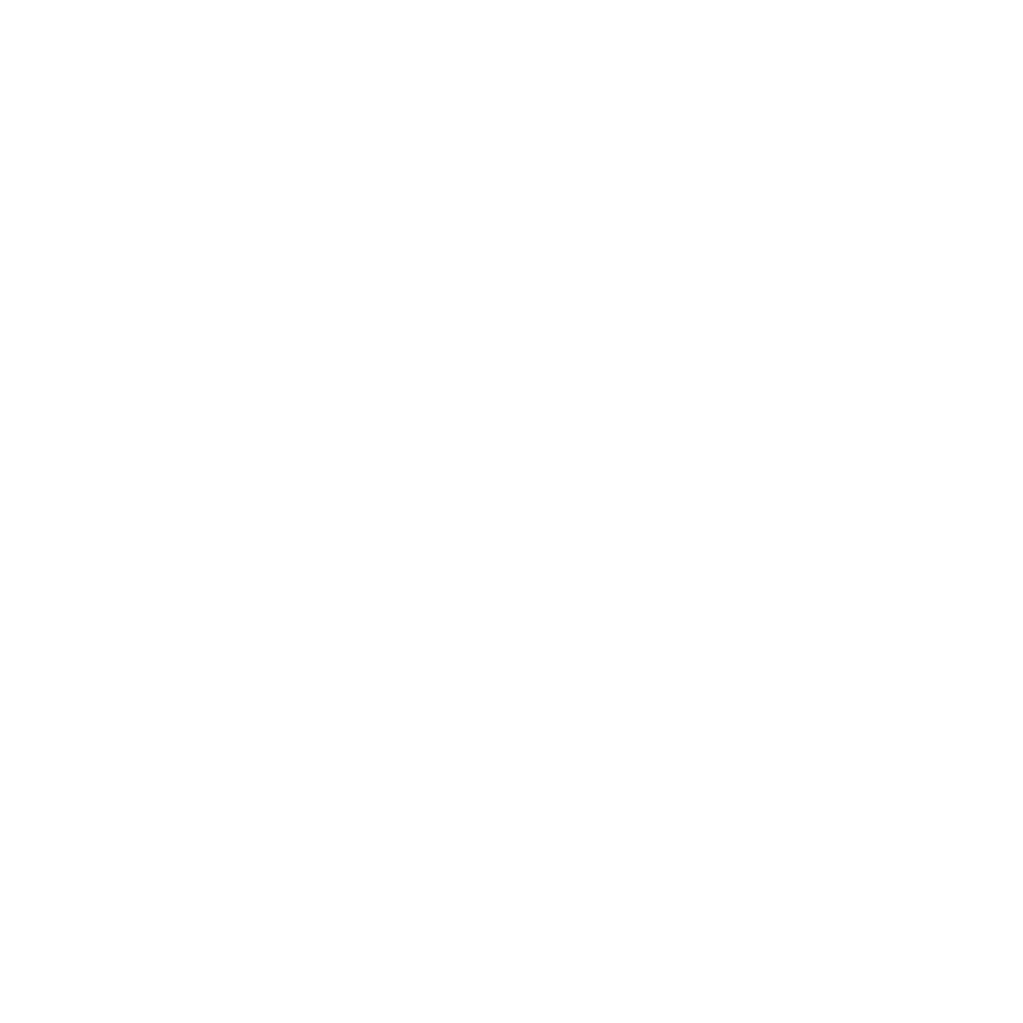

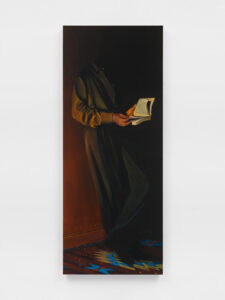

At Anat Ebgi, the show opens with The Poet (For Bolaño) (2025), a man half-swallowed by shadow, his book open to unreadable pages. The light that strikes him has no certain origin, recalling Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, and his talent for theatrics. It could be the spill of a lamp, or the errant glow of another world. “That uncertainty lends an eeriness to the work,” Hahne Quintana says, noting he had the Italian master in mind as he painted.

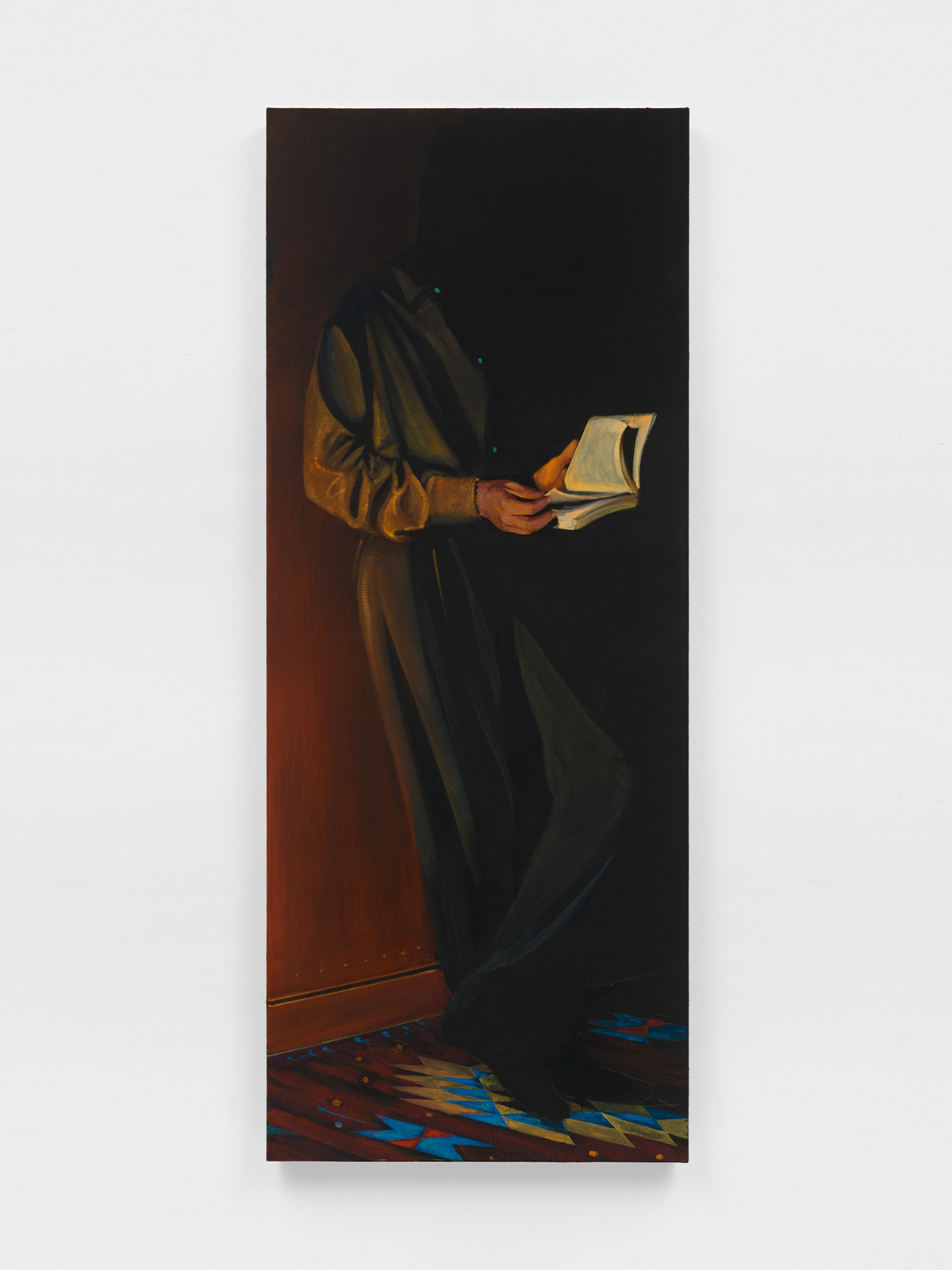

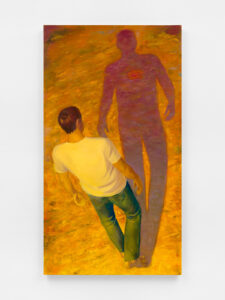

The artist is, in his own way, a storyteller. A Boy That Don’t Bleed is animated by the logic of parable, its central boy confronting his shadows, wrestling himself, and emerging luminous against darkness. In The Soul Is the Body’s Witness (2025), he tilts barefoot toward a silhouette larger and more defined than he is. The landscape summons the San Luis Valley Hahne Quintana frequented while grew up, an environment he links to both personal memory and the toxic afterlives of uranium “yellowcake” towns. The title comes from a poem Hahne Quintana recited in a performance earlier this year: “It’s about a body that thinks it’s impervious to suffering until it breaks,” he explains.

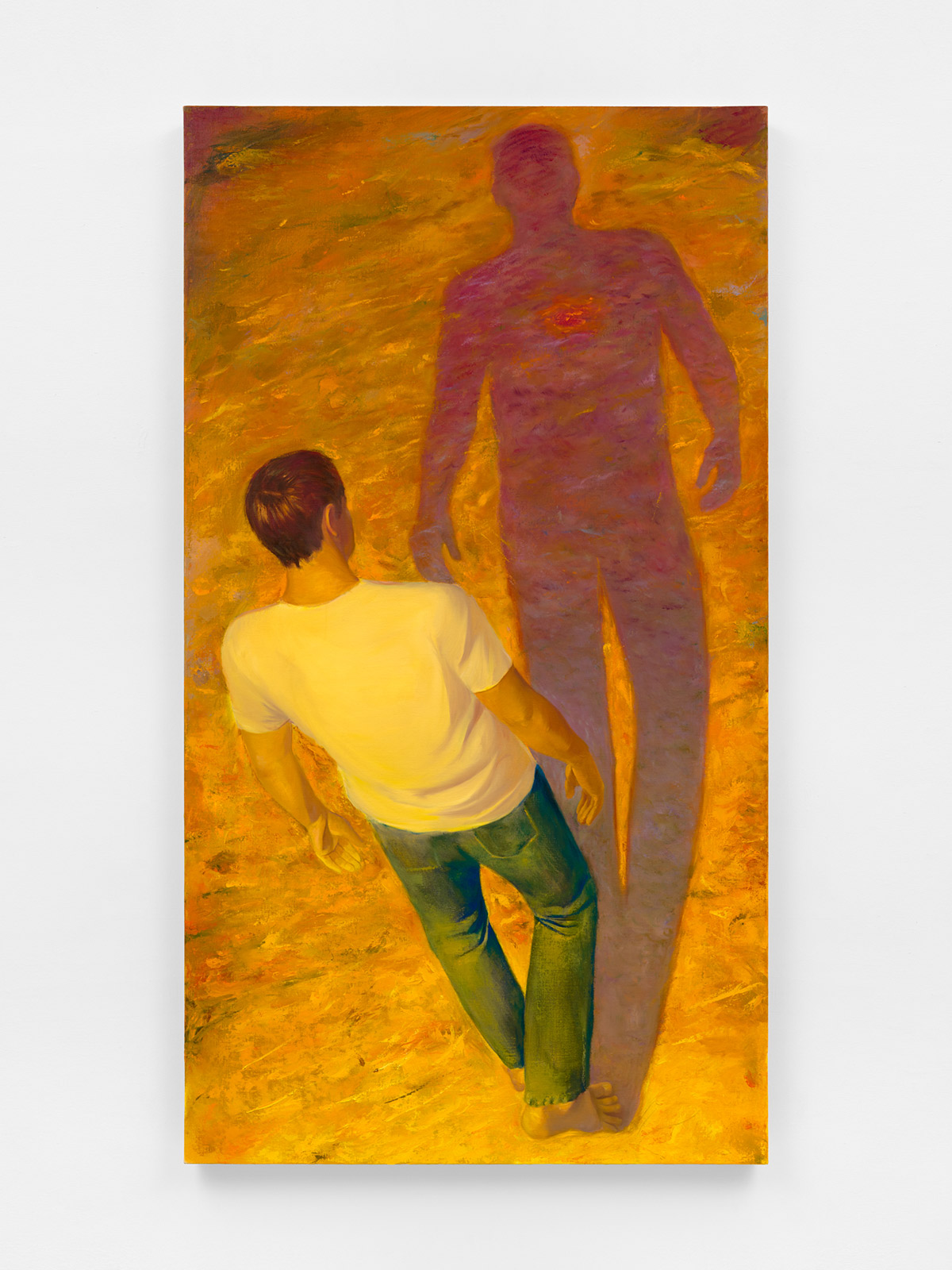

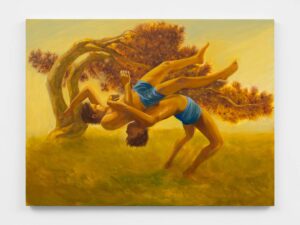

That tension heightens in The Boy Fights Himself (2025), where the figure and what looks like his duplicate lock into a suplex. The composition echoes the biblical story of Jacob wrestling an angel, a scene Hahne Quintana cites as a touchstone. “I have a nerve injury in my hip right now from wrestling, so it felt fitting,” he tells me, noting the painting’s roots in both scripture and his athletic past. Behind them, a Joshua tree bends almost into a spiral. Like much of the artist’s work, the western landscape entwines with the figures, binding their struggle to the land’s own history of endurance. Then the energy subsides. In Sleeping Colossus (2025), the boy curls on his side, his sunlit back echoing the ochre slopes around him. Where Goya’s The Colossus (1808–12) imagined a giant towering above the land, Hahne Quintana’s sinks into it, indistinguishable from the land that made him.

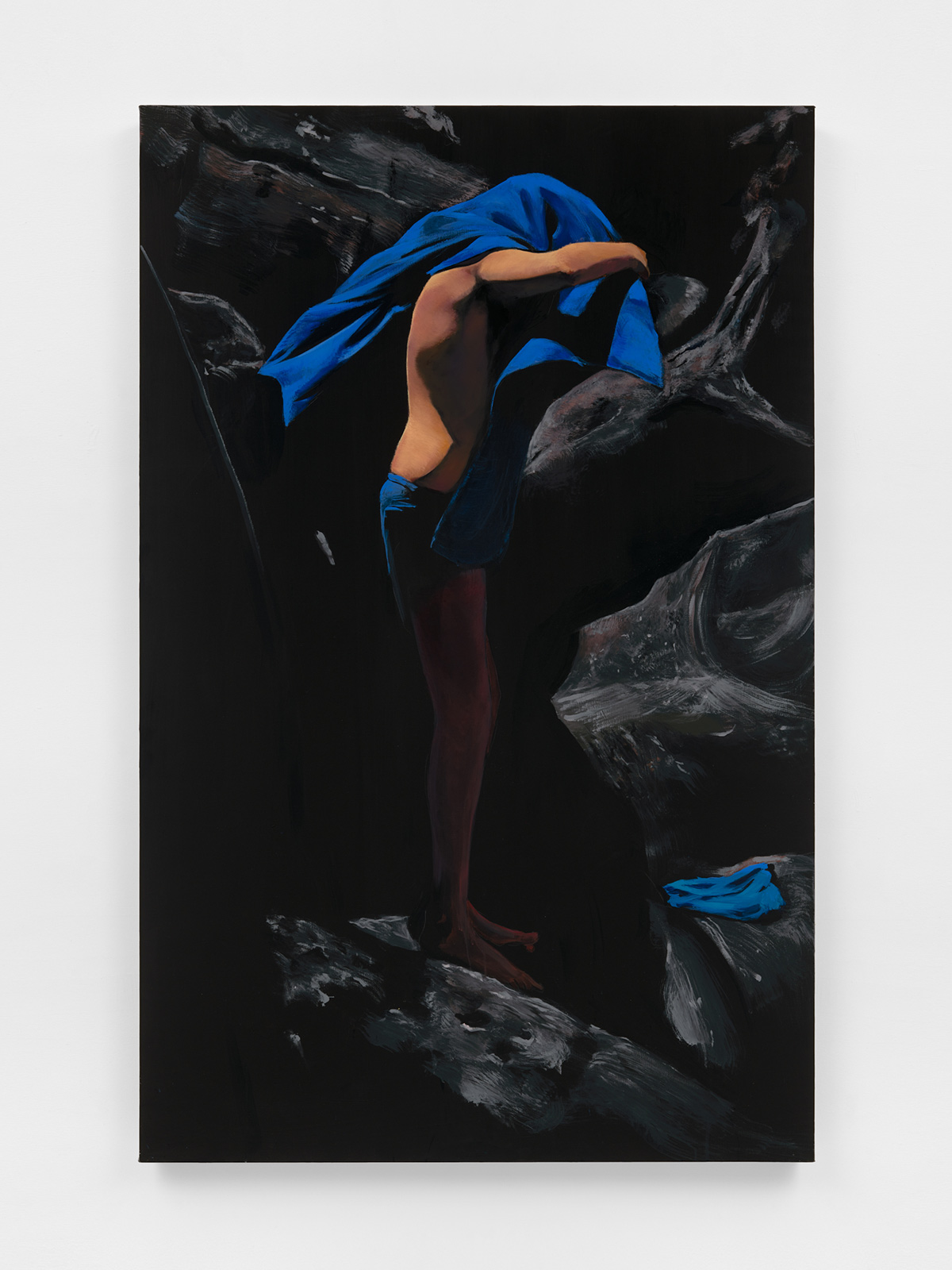

The black-ground works thrust the boy into the unknown. In Between Flesh and Stone (2025), he pulls a cobalt shirt over his head, his body half-consumed by the surrounding dark. “I almost never use that color,” the artist says. “It’s pure cobalt, which is often too much, but on black, while it pops, it also calms it down.” In Hour Without Shadow (2025), the boy lies on his back, eyes closed, his body bracketed by shadow. The pose recalls a coffin as much as a bed. Together with Sleeping Colossus (2025), the two paintings form a spectrum: one in which the figure merges into the landscape, the other in which he hovers on the threshold of death.

Hahne Quintana speaks often of volcanoes and caverns, of rocks as fossils of millennia. In this sense, the exhibition is not only a parable of youth, but also a meditation on how bodies, like landscapes, transform across time. Look long enough, and it seems the boy bleeds after all.

Caleb Hahne Quintana: The Boy That Don’t Bleed is on view through October 18, 2025, at Anat Ebgi at 372 Broadway, New York, NY.