With a new book and an HBO documentary, the photographer turns the lens both outward and inward, charting the messy, joyful act of becoming

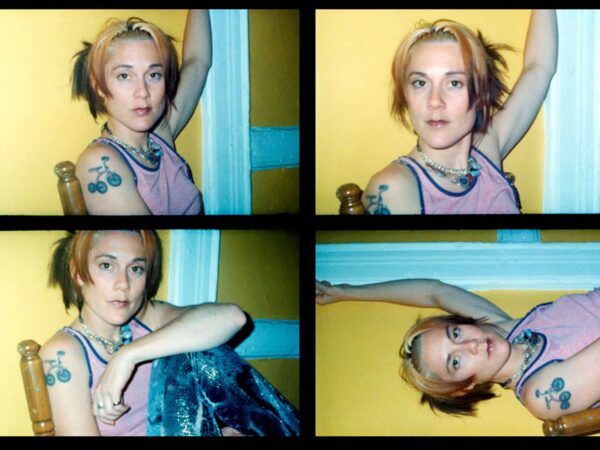

Two lovers embrace in a bathtub, their bare, clammy skin pressed against each other. This scene is from photographer Marie Tomanova’s book, Kate, For You, a series of portraits of her close friend, Kate Vitamin, and a former partner, Odie, taken over several years. When I met Tomanova for a coffee on a torrential Tuesday, there was something about her that compelled me to open up. That very intimacy characterizes Tomanova’s photography. It’s a feeling, but it’s also literal—taking pictures, she positions herself as close as possible to her subjects before the camera starts losing focus.

In the bathtub photo, rather than relegation to voyeur, viewers are invited into the couple’s affection. This vulnerability permeates throughout Tomanova’s oeuvre, a revered rawness she doesn’t take for granted.

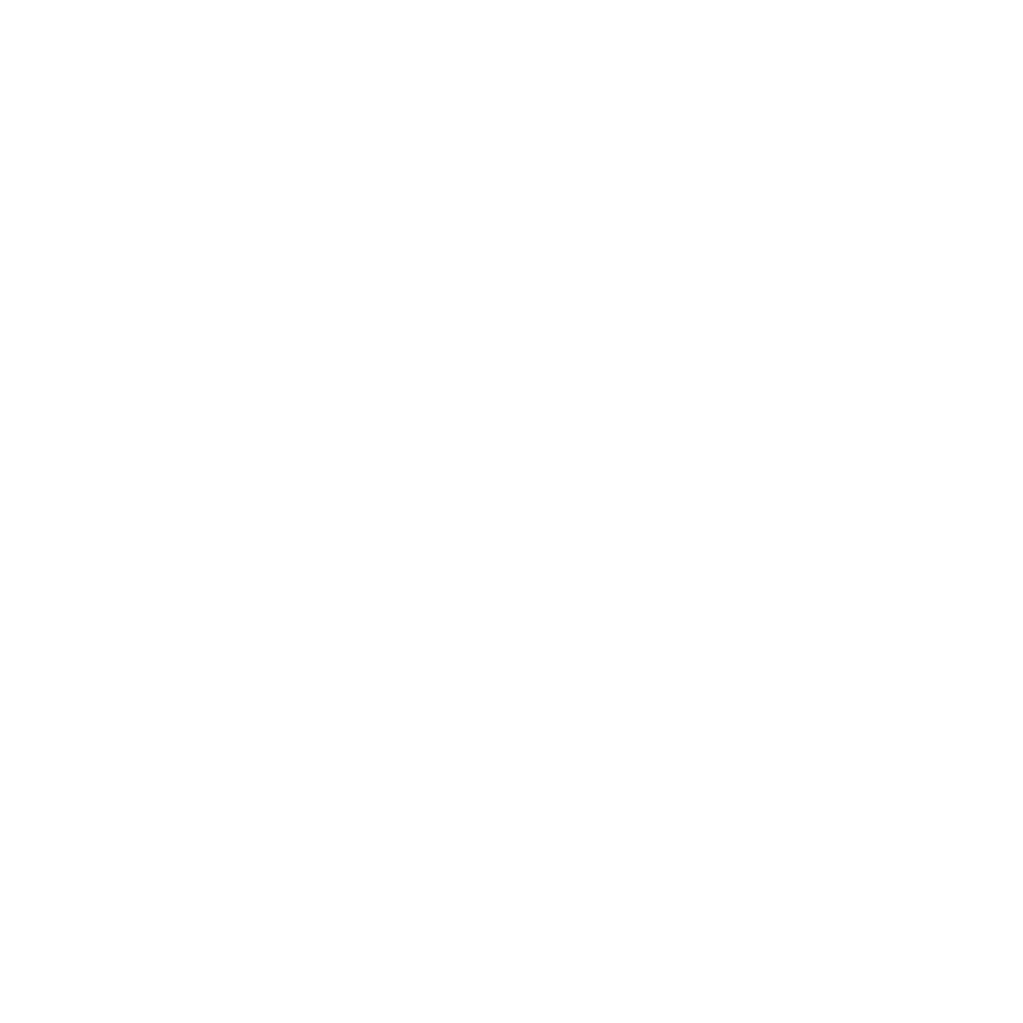

In World Between Us, an upcoming HBO documentary on Tomanova by Czech director Marie Dvořáková (which recently held its European premiere and will hopefully make its way to US audiences soon), a parallel scene unfolds. We watch as her partner, art historian Thomas Beachdel, shaves her head in possibly the same bathtub. This moment holds a similarly sacred awareness of the camera, best understood by a person who has held one as Tomanova has.

To view one of Tomanova’s photographs is not just to witness, but to be welcomed into a fleeting exchange—like a smile across the subway car where neither person averts their eyes, instead really looking and looking back. Sometimes this exchange is triangulated, between Tomanova and two people in love—which her tender lens has a knack for capturing, but it’s always between Tomanova and her subject. She outspokenly rejects the term “muse” because of its association with the white male gaze that’s ruled the photographic canon. Instead, she prefers “inspiration” or even “friend.” And many of her subjects are friends. As Tomanova shares, photography was initially a way for her to acquaint herself with the city when she first moved to New York from the small Czech village she grew up in.

These types of exchanges are growing more and more fleeting each day. As Kate, For You and World Between Us see their releases this week, Tomanova’s work and story serves as a reminder that the beauty of New York lies in the worlds of the people that make it.

Ahead of the launch of Kate, for You, and in the wake of the European premiere of World Between Us, Document sits down with Tomanova to unpack the two projects.

Anabel Gullo: Congratulations! First off, it’s a big week, between the release of your book and the European premiere of the documentary. For those who don’t know, can you talk a bit about the story that’s being told in the film—your story?

Marie Tomanova: Dvořáková first started filming me in 2018, two days before my first solo show. She thought that she was just doing a short two-minute portrait, and then she just kept filming, because things were happening. She kept filming for the next six years, and it became this humongous project when we launched it as a full feature documentary with HBO this year. But the real beauty in the documentary is the fact that for the first three or four years, we didn’t know that it would be a full feature. We didn’t know that it would be on HBO. So we were filming as two close friends, and it’s very intimate in that way, and very honest. And Dvořáková did a fantastic edit, because she had 450 hours of footage, and she built a story of those six years. I did not have any creative input on the documentary. It’s really her project. I’m just in the middle of it, the center of it, I guess, with my partner and art historian Thomas Beachdel, who I work with very closely. It tells the story of becoming, not just becoming who I am now, or becoming an artist in New York, but also coming back home to the Czech Republic, where I couldn’t go for eight years. I think it’s important, particularly in today’s climate, because I came to the US and I was an undocumented immigrant for a while, and seeing the current situation is really heartbreaking. I think that hope is something we can use right now, to feel like art matters and your dreams matter—whoever you are. So I hope that message will be felt strongly.

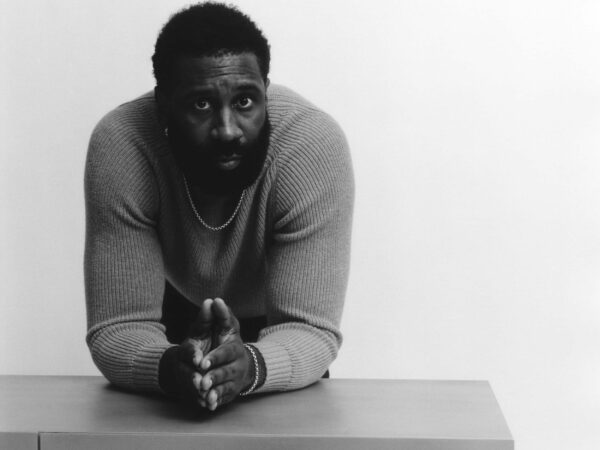

The book is a project that I launched as a museum show in the Czech Republic. It’s a longitudinal portrait that I shot of my dear friend, Kate Vitamin. I love her, and she has inspired me since the first time I met her. It’s interesting that I did a long-term project of photographing her over eight years, and that launched at the same time as the documentary, which is another person’s six-year project on me. So there’s something to be said for the longitudinal portrait of somebody, because you can capture a certain becoming who you want to be, and maybe not see it when you start photographing, but then over time you can trace this evolution and growing up. Growing up is something that I always felt scared of, because I always wanted to stay innocent and naive, wandering around and being amused with the world, but that’s just not sustainable. There’s the part of growing up that allows you to be who you want to be, not just that little child defined by your parents, but really becoming your true self, which I think is a powerful thing.

Anabel: You touched on something really interesting there, which is the parallel between someone documenting you and your own photographic practice, which is also to document other people. Looking at your work, there’s a sort of closeness that you’re able to create both physically through proximity to the subject, and also emotionally. This documentary has a similar sort of “intimacy,” like you said. How do you establish this in your work?

Marie: Photography wasn’t a medium that I studied at school. I’m originally a painter, actually. Photography, for me, wasn’t about creating perfectly composed, beautiful images, but about having a tool to meet people. Because I came to New York and I didn’t know a single person here, and I used to be really shy. Everything was a culture shock to me. New York is so different from the little town of 6,000 people in the middle of nowhere in the Czech Republic where I’m from. So to come up to somebody and say, ‘Hi, can you be my friend?’ I didn’t have the balls for that. I was like, how do I make friends in New York? And I realized that I could do it through photography. Because what I like is to meet people, talk to them, and share stories, because so many people come here with the same dream as I did, to become who they want to be. New York is still a beautiful place. It’s really rough, but it’s a place where you can find your people, you can find your community, because there are so many worlds in this big city. And for me, New York is not about the buildings or the places. It’s about the people who are here and create the energy of this crazy city. I realized that I can meet amazing, inspiring people here. And for me, the tool to do it was photography. Otherwise, I just didn’t know how to approach people. I didn’t go to school here where I would make friends. I didn’t have a job where I could make friends. I was an au pair and then a babysitter. I was far from the groups of downtown kids, so photography became a tool to meet new people.

The closeness is really what translates in there, because that’s what was so important for me about photography. And I think that you said it really beautifully. There is a literal closeness, especially in the early work, Young American, which had a show in 2018 at the beginning of the documentary. That show was really politicized in the media, as a portrait of the hopeful youth of the US and the US that I wanted to belong to, because it was when Trump was elected the first time, and I just couldn’t believe it. I was in California when it happened, working with friends at a farm seasonally so that I could survive in New York City. And I was like, How the fuck am I gonna get back to New York? Can I even get on a plane? Because I didn’t have my green card. I was still waiting, and that was really hard. The series was shot extremely close, actually most of it is shot as close as the camera would shoot. Any closer and it doesn’t focus. I think I was just trying to build a connection with the people in front of the camera to the point that I could be in their comfort zone, and it feels right, and we are both fine with it.

“The whole book is a collaboration, I would have never done it on my own. I need her. I need her to be her.”

Anabel: Lately this concept of a “muse” seems very popular. People love to talk about and look back at muses throughout art history. What do you think of that term in relation to your work?

Marie: I hate it!

Anabel: I was kind of hoping you would say that.

Marie: I don’t like to use it, I don’t like the meaning of it, and all the history of it, because to me, it strongly resonates with white guys objectifying women, or people in general. I just think it’s not what I’m going for at all. At the same time, what other good words are there? I say “inspiration,” because Kate [in Kate, For You] really inspires me. The whole book is a collaboration, I would have never done it on my own. I need her. I need her to be her. What really fascinates me about Kate and what I am endlessly grateful for is that she’s such an open and honest person. And it’s very hard. It’s courageous.

Anabel: We have to give credit to all the muses who have opened themselves up to this.

Marie: Right, because it’s not given, and it’s not easy, and sharing your inner self openly like that makes you vulnerable. And I think that’s where the power comes, but that’s also where it’s a little bit scary, for me too, because I never want to put anybody in a hurtful position. That’s why when I do self portraiture work, I can go even further, in many ways, because I know that I’m dealing just with myself, and there are responsibilities towards the others that I can just drop and don’t have to think about.

“I love when people are in love, and I love when they allow me to go into their world and photograph it.”

Anabel: On the note of Kate, For You, and the way that you seem to be very public about your own relationship, you have an aptitude for capturing love and intimacy between two people on camera in your work. Is that something that you have a particular interest in?

Marie: Who doesn’t? I remember from my years, being in love was the most powerful feeling I could feel when I was young. I was 16 years old, when I first really fell in love, it was in a long relationship. It was the strongest emotion I’ve ever felt. It’s beautiful when that happens. And I think that it’s emotions that go beyond the understandable or something you can describe in words, which I guess is why there are certain poems or images or songs. Because love is amazing. I love when people are in love, and I love when they allow me to go into their world and photograph it. And very often that just happens because they’re so happy. There’s a certain happiness that comes with that. It’s very special.

Anabel: It’s been a major year. What’s next for you?

Marie: I currently have an exhibition on view until the end of June at Her Clique gallery in Lisbon. It’s called I Love Seeing You.’ I worked on it with the curator, and she wanted to put together my very early self portraits in nature, from 2016 and ’17 with my latest self portraits titled Untitled Portraits, which show me putting on these different characters. It’s such a vast difference between me nude in the American landscape, where I’m trying to see myself as someone who belongs in this place, seeing myself in the landscape in order to understand that I do have a place in this country. Most of them don’t show my face, which I think was an inner struggle with not knowing what my identity really was because those were the confusing beginnings, and then these latest portraits are the exact opposite. It’s all about the face, the identities, the different characters that are all part of me and just exaggerated and put into the whole identity. It’s very strongly inspired by Cindy Sherman, of course, and her Untitled Film Stills. And Andy Warhol and his polaroids of the cool kids of downtown New York that I always wish I could live through.