Following her retrospective at Metrograph, the filmmaker and choreographer meets with Document, testifying to the creative power of nonconformity

In her 1965 “No Manifesto,” Yvonne Rainer wrote: “No to style […] no to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer […] no to moving or being moved.” These positions seem untenable for a choreographer to take up, and yet Rainer’s refusal of conventional dance aesthetics would make her into an artistic icon. Though she would later revise aspects of the manifesto, Rainer is today recognized as one of the pioneers of postmodern dance, a style characterized by the repetition of everyday movement and an emphatic non-theatricality; by recuperating the simple gesture or the casual walk, she brought about a total subversion of the narrativity and spectacle of ballet and modern dance. Like all of the artforms to which she has since turned her hand, Rainer’s negation of aesthetic ‘rules’ has yielded tremendous innovation.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Rainer made her mark within experimental circles of conceptual artists in Lower Manhattan. Best-known for her work at Judson Memorial Church, she took part in the notorious exhibition slash anti-war protest People’s Flag Show, performing her famous dance Trio A wearing nothing except for a loosely-cinched American flag. Other participants included Abbie Hoffman and Kate Millet, and many were charged with the crime of flag desecration.

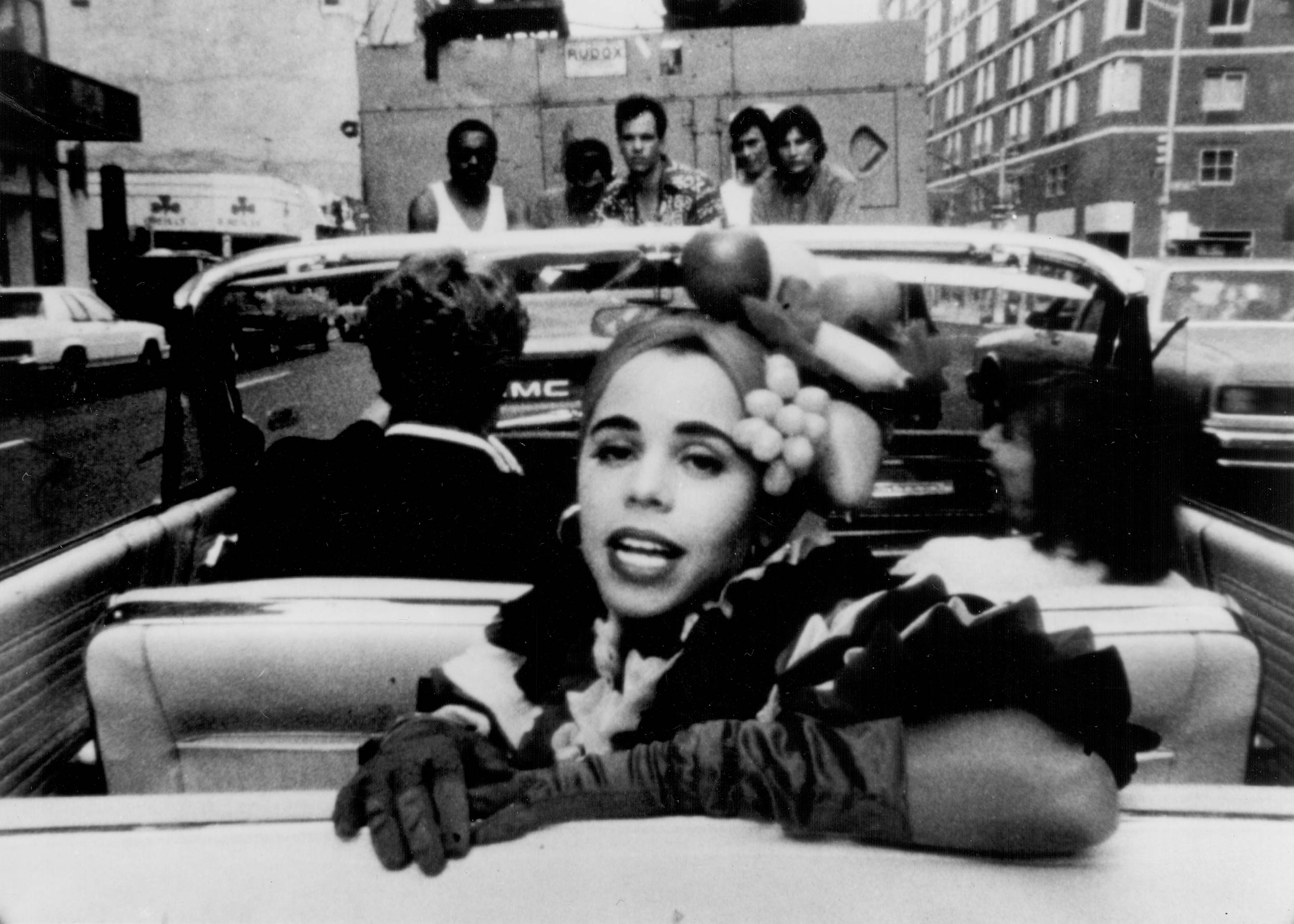

Shortly thereafter, Rainer would stop dancing and begin to make films, all of which take up a similarly oppositional stance, divesting of Hollywood—and narrative—conventions. In the ’70s, Rainer was influenced by the psychoanalytic film scholar Laura Mulvey, whose essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” would coin the now ubiquitous concept of the “male gaze,” interrogating the objectifying pleasures of looking and being looked at. Consequently, Rainer’s films are often opaque in style and highly-mediated, disrupting any naturalizing tendencies on the part of the viewer. They blend dance with writing and even, in her final film Murder and Murder (1996), a boxing match.

Though Rainer resigned from directing more than two decades ago, her films endure as touchstones in US experimental cinema, attesting to her ongoing status as an iconoclast and artistic visionary. Document spoke with Rainer this February, on the eve of the debut of new 4K restorations of her films, premiering at Metrograph. At 88, she recently announced her retirement from choreography, though she remains keenly invested in the creative power of nonconformity—a tradition of which she is an indelible part.

Tia Glista: I’m thinking about the era in which you began your career, in the ’60s and ’70s, and I’m struck by the cross-fertilization of artforms that seemed to produce so much invention at that time.

Can you talk about creating amid such an interdisciplinary milieu, and how that shaped your own artistic sensibility?

Yvonne Rainer: I came into the [Merce] Cunningham-[John] Cage scene at a very opportune moment. We were all reading Cage’s writings and going to his concerts. And then there were Happenings, and it was a much smaller art milieu—you saw the same people in the audiences all the time. There was a lot of cross-fertilization among visual artists, composers, musicians, choreographers, and dancers. It was a very heady, productive time for a lot of us who were exposed to all these ideas. I can attribute my early solos to challenging previous modes of choreography that had been done with the Martha Graham Company, and all those people who were showing their work in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s.

Tia: It also strikes me that this kind of inclusive, experimental, cross-disciplinary atmosphere seems related to a kind of non-virtuosity that you promoted—for instance, some of your performers were not trained dancers, but other artists or friends. What were some of the advantages of not relying on a compulsory idea of technique or training?

Yvonne: Well, Steve Paxton and I used to joke that he invented walking and I invented running [laughs]. But, you know, I was never a purist. So, my running dance for about a dozen people was accompanied by a very bombastic piece of music, and I was always mixing it up, using everything I was learning. There was a duet with Trisha Brown, where I performed a balletic routine that I learned in class, while she did bumps and grinds from burlesque simultaneously. I was going to the New York City Ballet, and I was very struck by some of [George] Balanchine’s abstract work. It all coalesced in these very extended references to different forms of dancing—all these multiple influences from my training, and what I was being exposed to with minimal art.

Tia: Your choreography and dance work appears in your films, as well. What, for you, is the relationship between dance and film?

“I had aspired for a very short time to get into the Cunningham Company, but they were all very competent in ways that I was not. I knew very early that I had to make my own work.”

Yvonne: That’s a whole history. I had been very ill, and when I returned to dance in my late-30s, early-40s, I felt I had exhausted the kinds of things I was doing [before]. I had been exposed to experimental film, like Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren, from a very early age. So film seemed to be a way of extending my interests—political interests, social interests, fiction and autobiography, the feminist movement, and so on. I didn’t use professional actors, so it was natural that I use dancers. I showed them [in Lives of Performers] as fictional characters who were rehearsing a dance—that is, dances that I was making. So it’s a whole other way of making a collagist kind of narrative.

Tia: I’m always fascinated by the way that both dance and film pay such a particularly acute attention to the body. Looking back, what was your relationship to the body as a younger person, and how did that inform or develop through your later creative work?

Yvonne: Well, I came to New York at a very young age, 20 or 21. I wanted to study acting. In the late-’50s, the Stanislavski method was the primary technique that prevailed, and I was told, very shortly in studying it, ‘We don’t believe you.’ I was not going to be successful in this mode, but a friend of mine was going to a dance class by a modern dancer named Edith Stephen, at a studio in the Village, and I took to it immediately. I loved working with my body. I had very strong legs, I could jump and run around. Unbeknownst to me at the time, I had no turnout. I have very, very narrow hips, and so I quickly realized I would not be accepted into any professional modern dance company. I had aspired for a very short time to get into the Cunningham Company, but they were all very competent in ways that I was not. I knew very early that I had to make my own work.

Tia: I have read a few interviews where you’ve referred to the very gestural aspects of your choreography as ‘quotations.’ Can you say more about this idea of quoting with the body?

Yvonne: I’m still quoting, in a way. My most recent piece of choreography for nine people is called HELLZAPOPPIN’: What about the bees? The main source of movement is the jitterbug section of a Hollywood film called Hellzapoppin’, and it consists of these amazing young dancers doing acrobatic partnering. I have a group of dancers who are from the age of 30 to 65, and I knew at the outset that they would not be able to do these things anywhere near the original source material. So I divided them into two groups and left them on their own to interpret this material. I show the original at the beginning of the dance, so the audience knows what we’re creating from.

Tia: This idea of quoting certain gestures or styles became incredibly important, in the ’80s and ’90s, to ideas of gender as performance.

Yvonne: Yeah, that was one of the ways I felt I could challenge the ballet tradition, and what I saw as its limitations. The man is always [partnered with] a woman, so in this last work, three women lift a man and do amazing things with his body.

Tia: You’ve also talked, around the time of Trio A, about becoming aware of the pleasure that you took in being looked at as a performer, and wanting to resist this. The idea of spectatorship exerting pressure on the body is also raised by Laura Mulvey, whose writing on the male gaze of cinema impacted your work. What did you want to say or do about this problem—of the politics of looking or being looked at?

Yvonne: [In Trio A], I gave myself the challenge of never facing the audience—which was a direct challenge to the ballet solo, which is so exhibitionist. There’s a lot of gesture, and the changes in the phrasing are not perceptible in the way they are with traditional dance, and especially with ballet.

Tia: Your filmmaking is often described as feminist in nature, and over the last couple of years, feminist cinema has started to become more mainstream. But it also often feels, to my mind, more inadequate. What—to you—must a film do in order to call itself feminist?

Yvonne: Well, yeah—there are references to lesbianism, and I’m challenging stereotypical gender relationships in dance. And in [2020’s Revisions: A Truncated History of the Universe for Dummies / A Rant Dance, Lecture, and Letter to Humanity], racism, too, is a problem that is tackled in the voiceover by Apollo, who comes down from Olympus to try and fix things in this country, and runs into a lot of frustration. This last program incorporates both my dance history and the political concerns of my films, which is unique—I always separated the programming of dance and film.

Tia: You have your Metrograph retrospective coming up. When was the last time you rewatched your own films? And what is it like for you to look back on them?

Yvonne: Oh, just last week in Washington, DC. I watched the first one, Lives of Performers. And I’m going to talk after the first Metrograph showing of it. That particular one… I mean, I always say right after, ‘They don’t make them like that anymore.’