Ahead of the latest installation of their Site-Specific Dances series, the architect and choreographer discuss building from a legacy, and designing for performance

When Dino Kiratzidis and Michael Spencer Phillips—an architect and a dancer, respectively—were married, they didn’t expect their professional lives to merge alongside the personal. Over the years, however, they’ve cultivated what the latter calls a “little combined brain”: two artistic missions, based in far-apart disciplines, which came together to surpass the conceptual bounds of either individual calling. Site-Specific Dances was born, digging into the synthesis of performance and place.

What began as a study on the theater of the natural world—dances staged and choreographed around sand dunes, flowing creeks, and redwood groves—eventually necessitated deeper thought. “We had to begin to deal with the social, political, environmental implications of sites,” says Kiratzidis. The pair then pivoted to the realm of urban public space; in 2022, for instance, Movement Bridge made use of religious sites around Northern Ireland, interrogating the impact of the Troubles on local community members. Phillips recruited a 50-member, amateur dance crew for a 15-minute performance, from kindergarten-aged kids to elders coming up on their 90s.

Site-specific dance, as a concept, is nothing new. Kiratzidis and Phillips draw from the legacy of the ’60s and ’70s—trailblazers like Trisha Brown, Heidi Duckler, and Pina Bausch, who founded the movement alongside their contemporaries in a bid to escape the confines of the traditional stage. In this new era, however, “site is more.” It’s a character driving the narrative; a performer in its own right—in part, due to the technology on offer in the performing arts today. Offers Kiratzidis, “When we shoot with a drone, sometimes the dancers get so small they become diagrammatic, and the landscape becomes part of the performance. We’re coloring in between the lines.”

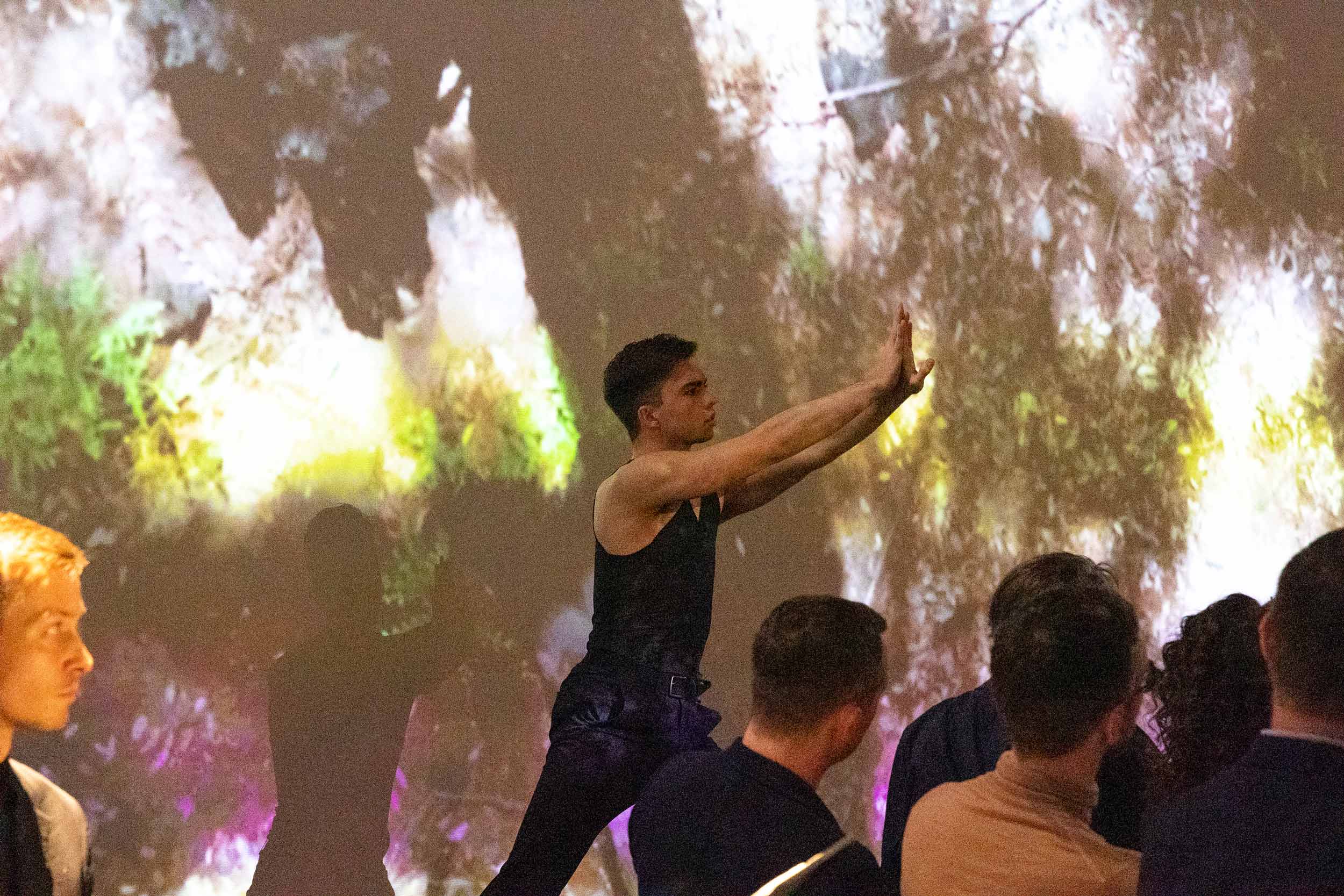

Last Thursday, the pair showed in New York for the first time; a “proof-of-concept” endeavor, where site-specific work could be translated from the wide expanse of nature to the stage and the screen. Kiratzidis and Phillips took to Paul Taylor Studios—joining forces with composers Polina Nazaykinskaya and Darian Donovan Thomas and video editor Emma Kazaryan—to premiere an original exhibition-performance, along with immersive videos of past work, set to the stylings of a 16-musician chamber orchestra. Ahead of the show, they met with Document to discuss the power of interdisciplinary collaboration, and their mission of bridging art with real life.

Morgan Becker: How’s the lead-up to Thursday’s show going?

Dino Kiratzidis: It’s very interesting, because we’re completely designing this performance from scratch. Typically, in a concert or dance performance, you have a stage and you have the audience. We have a checkerboard layout that intersperses the musicians with the audience. We have a chamber orchestra, and we have video. It’s kind of stressful, how all the things are coming together. But, you know, we have really amazing people working on the various parts.

Michael Spencer Phillips: I’ve been a performer over and over and over again; I was a dancer for 22 years. I’ve even been a choreographer. But this is really different, because I’ve never put together a dance with five composers, with a live violin soloist. It’s very rare to see all of these elements together, at the same time.

Dino: There’s dance that’s on-screen, and then there’s the live component. The dance that’s on-screen is from our location-based work. One of the things that we’re doing is sort of inventing a format for showing site-specific work. Like, if you put dance on the side of a mountain, there’s no real way for an audience to see it. We’ve [found] a way to translate.

It’s not a fixed way of presenting it. Paul Taylor Studios is a site that has a particular size, and we’ve invented a way of showing pieces in that space. If someone gave us an abandoned warehouse in Brooklyn or a gallery at MoMA, we would have a different show. Our initial projects were very much simply about the questions, Can the landscape become a stage? How can we reveal the theatrical potential of found spaces? Is the sun a special effects machine? As we began to do new projects, like MEGAFLORA, we realized that the notion of sites is actually so much deeper and richer. We had to begin to deal with the social, political, environmental implications of sites.

Morgan: How does your creative process work, chronologically?

Michael: For the site itself, we have a very initial idea. We try to immerse ourselves there, connect with community organizations, youth organizations—find all these points of contact.

Dino: In Phoenix, we networked with local rock climbers, who basically made the project possible. With MEGAFLORA, we’ve set up a series of interviews with Indigenous leaders, scientists. It’s a way of bringing the real world in, in some way, shape, or form.

Michael: With our project in Northern Ireland, Movement Bridge, people really started to shape the way that the project was going to evolve. Over a six-month period, I gathered a group of individuals that would participate in the building of the work. We ended up having a lot of uncomfortable conversations about the Troubles, and the impact of the Troubles on their community—then the similarities and differences between the youth and elders of the town, and what it meant to be a human rights activist in the ’60s, versus what it means now.

We had all these different ways of communicating with each other. And when it started to get heated, we would turn to phrases of movement. I would guide the process, weaving those phrases together into longer pieces—and eventually, we made a 15-minute performance work with 50 participants between the ages of five and 85, both Catholic and Protestant. It took place at different sites around the city, which had [religious] significance.

Dino: The thesis point of the project is, How can we break down the barrier between arts and real life?

Michael: Every project is a little bit different in that—you know—I’m continuing to evolve as an artist; Dino is continuing to evolve as an artist. As a partnership, that’s like a third artist—a little combined brain. When something strikes [one of us], we start to poke around, we start to think about the point of entry. I want it to be the one that hasn’t been thought of, that not everyone else is going to do.

Bringing dancers into those forests creates a sense of empathy, creates a sense of scale. And also places a human in front of, you know, the wreckage of our own doing. Those images are powerful.

Dino: One of the most important things about our project is that it’s an extreme example of collaboration. There are so many people involved, and it’s so open to collaboration with different disciplines. [There’s also] our primary partnership, Michael and myself. We’re married, so there’s a biographical angle—we bring together two different fields, dance and architecture. Of course, we’ve been thinking about some of the historical moments where dance and architecture have kissed.

“Bringing dancers into those forests creates a sense of empathy, creates a sense of scale. And also places a human in front of, you know, the wreckage of our own doing. Those images are powerful.”

Morgan: How do you think about the legacy of site-specific dance, starting from the ’60s and ’70s? Who are the influences there?

Michael: Pina Bausch is probably my greatest influence. I just love her physicality, and the vulnerability of her dancers. She was essentially bringing these environments into a theater. I’m interested in taking the dance out of the theater—but she is a huge influence of mine.

There were also these old, shaky videos from a helicopter, filming [Robert Smithson’s] Spiral Jetty. Being able to see that land art in a very raw way… You could see that [landscapes have their] own movement and their own drama.

And then, obviously, Anna Halprin—

Dino: Who, by the way, was married to a landscape architect, Lawrence Halprin. We think about them a lot.

I want to say one thing about size specificity. There was a moment in the ’60s and ’70s [when] site-specific work became a thing. But I think we’re actually critiquing some of that approach and saying, site is more. When we shoot with a drone, sometimes the dancers get so small they become diagrammatic, and the landscape becomes part of the performance. We’re coloring in between the lines.

And then my influences: One of my biggest is Xenakis. He was an architect, a contemporary of Le Corbusier. And then he became a composer of electronic music. What I find really interesting about him is his spatial arrangements of music. There were these beautiful drawings he made of distributed orchestras—that’s actually the influence behind our own distributed orchestra, that we’re having in our show. Xenakis and Le Corbusier made a very famous building called the Philips Pavilion, designed specifically for the performance of electronic music and projected visuals. There is something about that overlap—designing performance—that is super, super interesting to me.

Morgan: Where would you like to take the project next?

Dino: I think the big goal right now is to fully complete MEGAFLORA. It’s half environmental ballet, half interviews, but they’re not quite documentary interviews. Darien Donovan Thomas, one of the composers, is going to turn them into soundscapes. They’re [made] in collaboration with the Sempervirens Fund, which is the oldest land trust in California.

Michael: [We’re working with people] who aren’t necessarily just artists. Curiosity and humility have to go hand in hand. We’re environmentalists, but not environmental scientists. I don’t understand the facts and the figures. Working with a burn boss—an expert in prescribed fire—she’s talking about things I’ve never heard, never understood. If there is an element of real-world issues [in our work], we want an expert informing that.

We’ve met so many wonderful people along the way, just by being humble and saying, ‘We could really use your help. We would love for you to be a part of this.’

Morgan: What are you hoping to leave your audience with?

Dino: Potential. This is like a proof-of-concept presentation for us, in a way. It’s showing just enough, at the scale we can afford, for people to understand our concept. And then from there, it’s just bigger and better.

Michael: It sounds a little cliché, but during the pandemic, we spent a lot of time together, Dino and I. I felt like my life was being set up—for me to be a choreographer for stage. Dance is the language I speak. It’s the language I’m most comfortable with. But I wanted my career in dance to mean something. The arts are extremely powerful, building bridges, creating understanding among people. That’s what I want to do with my dance career: I want to collaborate with as many people as possible, and remain teachable, and keep engaging. And it’s such a gift to employ other artists—like, that is the best feeling in the world, to be able to pay artists.

Dino: I’ve been an architect for quite some time now. Before I was an architect, I studied music for a year, and I was really interested in the performing arts—obsessed with theater and opera and music and so on. I never thought I would have the opportunity to be anything more than a consumer of things. [This project] gave me this way of using my architectural skill set to think about performance. And we might be able to unlock things that, you know, just a choreographer or architect wouldn’t.

Michael: As we’re preparing for these performances, our life is getting bigger in a lot of different ways. There’s immense gratitude between the stress. I feel like I found the right person, you know? You can’t unring that bell—of your partner being your collaborator.