With transgressive body-morphing designs, the Australian artist celebrates the features shapewear often serves to hide—satirizing oppressive patriarchal standards in the process

Corsets get a bad rap, and often for good reason: They’re tight-laced, restrictive, and emblematic of the patriarchal standards of yesteryear. But for couturier and artist Michaela Stark, the political history of the garment—and its ability to sculpt and shape the body toward unnatural ideals—makes it a potent tool for social critique. Designed with the individual in mind, Stark’s transgressive body-morphing lingerie accentuates the wearer’s natural bulges, curves, and rolls—subverting the intended function of shapewear by highlighting the features it so often serves to hide.

Stark’s interest in the politics of the body stems from personal experience. Growing up plus-size, her clothes were always snug in all the wrong places, and the inability to find garments designed with her body in mind resulted in countless small, private traumas: crying in the harsh fluorescent light of a dressing room the first time she went bra shopping, or sucking in her stomach for hours to avoid the possibility of visible rolls. There was a sense of her body overflowing its bounds—a loss of control, which she has since reclaimed by emphasizing the same features that once made her feel dysphoric. “I never knew how to make my body look the way I wanted growing up,” she says. “Now, it’s in my control—I’m no longer fighting the way my body wants to be. Instead, I’m pushing it further in that direction.”

It’s a practice that began with self-experimentation, with Stark taking self-portraits and sharing the results on social media to a small and supportive audience on Instagram—one that has since expanded to include some 155,000 followers, attracting the attention of celebrities like Shygirl and Beyoncé, for whom she has created custom pieces. As Stark gains more widespread recognition, she’s facing new challenges, like her desire to make garments more financially accessible without sacrificing their quality.

“I wanted my first collection to be a replica of the work I’ve been producing for the past few years, which you can finally buy. But because it’s couture, it’s hand-stitched and hand-dyed silk, and hand-embroidered—which means the price point is high,” she says of her namesake made-to-order collection. She now has plans to release a new line geared toward younger audiences, at a more accessible price point. “As a designer, I put a lot of work into these garments—not only making them ethically, but also learning the craft behind it. It’s slow fashion. At the same time, I think what I’m doing resonates with [an audience] who can’t afford couture, so I want the people who actually love and support my work to be able to be a part of it.”

“All the photos on my Instagram were portraits of me—some in body-morphing designs, others in more conventional ones. If you think one of those images is disgusting, that’s just showing you how you view the body.”

Stark’s focus on individually-tailored designs is a response to the current fashion system—one in which even plus-size clothing often misses the mark, due to fundamental misunderstandings about body diversity. “Even if garments get graded up in size, the fit often doesn’t work, as you encounter different body types. For example, one size 14 will have drastically different proportions than another size 14,” she says. “I know what it’s like to put myself in these clothes—that’s so deeply personal to me. Even as I grow my brand beyond myself, I want to keep that central theme around the individuality of the person who’s going to wear them.”

To some, the personal experience underpinning Stark’s practice is obvious; to others, it’s a source of persistent misunderstanding, some of which she’s documented on her Instagram stories. “Unfortunately it looks like this designer enjoys trussing up women like chicken,” says one commenter. “A misogynist’s dream,” says another. “WTF is being done to women? If Beyonce is appearing in such designs, she needs a jolly good talking to!”

But for every misinterpretation of her work, there is a thoughtful debate for its merits. “I think repulsion is either a result of pure philistinism, or just discomfort with perceived imperfection,” argues one woman in Stark’s comments. “In a way, she is using absurdity to decentralize a body whose identity has been so closely tied to obsessive appearance, and [satirizing] the industries that impose those standards on us.”

Sometimes, people assume that Stark is a man, interpreting her Instagram handle, @michaelastark, as “Michael A. Stark.” She has been accused of subjecting plus-size women to cruelty and humiliation because her garments accentuate the appearance of common insecurities, rather than concealing them—something she views as celebratory, but which acts as a cultural bellwether for attitudes surrounding the body. “I had people commenting that the way I dress skinny models is beautiful, and the way I dress fat models is horrendous,” she says. “But at the time, all the photos on my Instagram were portraits of me—some in body-morphing designs, others in more conventional ones. If you think one of those images is disgusting, that’s just showing you how you view the body.”

Equally challenging is the censorship she faces across social media platforms, which frequently remove or suppress her content—even if there is no nudity involved. According to Stark, this is common not only with her work, but also with that of many artists in her community—particularly plus-size people of color, or creators whose work showcases body diversity. “When you’re changing the mold, and mainstream systems haven’t quite caught up, your work will be censored,” she says, “and that just means that change hasn’t happened yet.”

Ironically, it’s the posts that resonate most with audiences that are in danger of being flagged for removal. “Whenever something goes viral,” she says, “that’s when I know it’s going to be taken down.” The suppression of divergent voices in fashion is a problem that extends beyond social media: “Often, models are chosen because of their distinct perspective and politics, yet they have zero control of what happens on set. Even if brands are choosing to feature someone who’s in charge of their body and sexuality and image, that often isn’t true of the result,” Stark says, explaining that while efforts are being made toward more diverse casting, a lack of representation behind the scenes results in superficial forms of progress.

“When you’re changing the mold, and mainstream systems haven’t quite caught up, your work will be censored, and that just means that change hasn’t happened yet.”

Similarly, plus-size models are on the rise—but for the most part, the “diverse” bodies being celebrated still adhere to conventional beauty norms like the hourglass figure. It’s part of why Stark has chosen to showcase less-commercialized aspects of the body in her work: Features that, while common, are less readily integrated into dominant notions of sex appeal. For Stark, the practice of playing with these norms has been transformative: Not only does body-morphing serve as a form of artistic experimentation, but it has also become a way for her to test and push her own limits physically, putting her in touch with the needs and desires of a body she’s often felt estranged from.

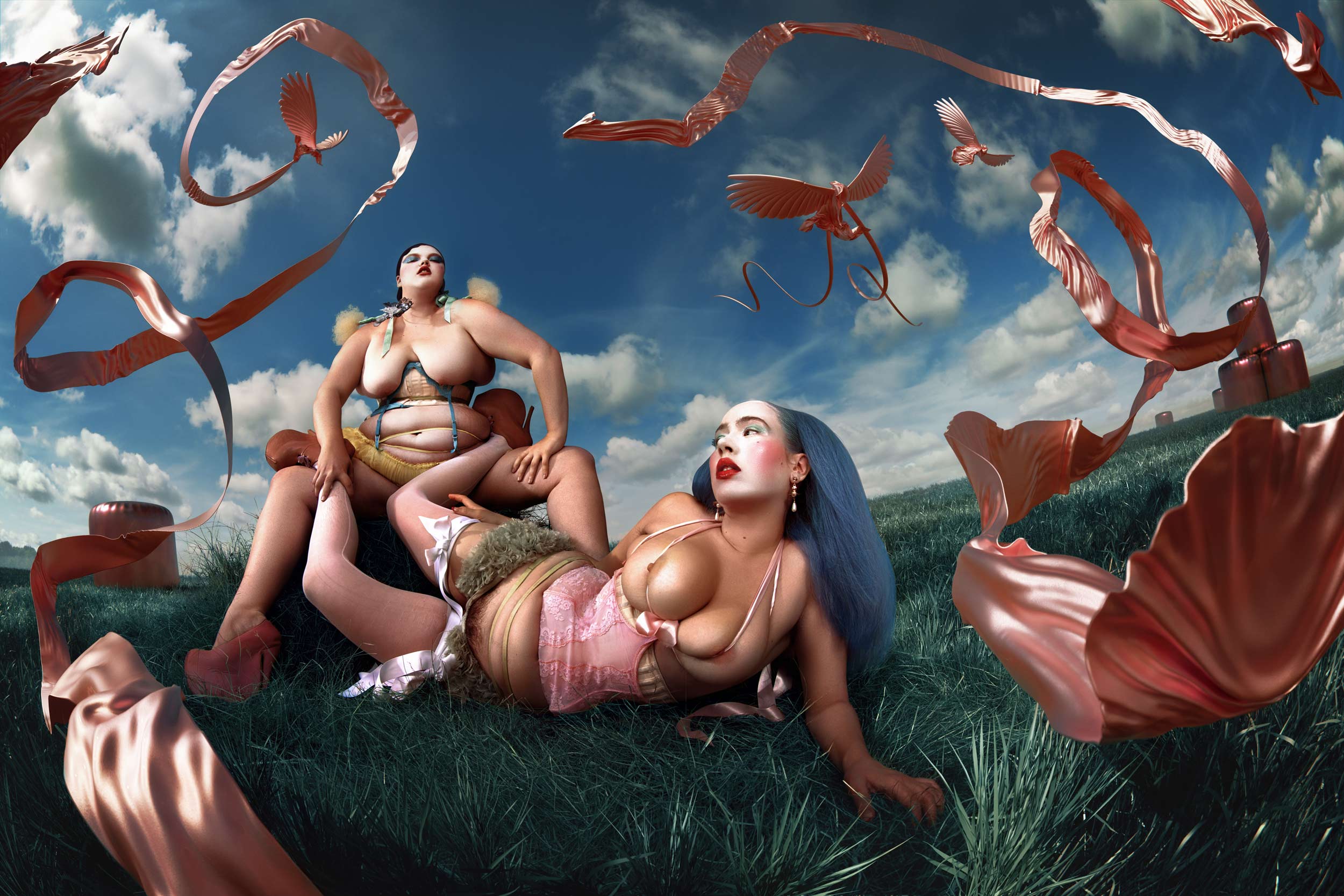

“I’m interested in exploring whether, through fashion, it’s possible to make something that is inherently grotesque, but also inherently beautiful,” she says. While Stark’s work often foregrounds the raw and real, it also contains a sense of femininity and fantasy—aspects she explored in a recent collaboration with photographer Charlie Chops, who she says “was able to bring her work into that sphere in new ways.” Often utilizing delicate materials like organza, taffeta, and silk, Stark aims to create a world in which more familiar notions of beauty can coexist with bulges, rolls, and curves, drawing attention to the gap between societal ideals and the more common lived reality. This overflow of flesh serves as evidence of the pressure to conform, forcing the viewer to grapple with discomfort these ideals create—yet there is also a real sensitivity and appreciation of beauty, evident not just in her depictions of the body, but the qualities of the garments she uses to shape it.

Hyperfemininity is having something of a cultural moment, with the rise of bimbocore spurring dialogue around whether it is truly subversive to embody an aesthetic that could, in one sense, be interpreted as catering to the male gaze. Yet in another, women self-consciously embracing artifice over effortlessness—whether in the form of corsets, visible makeup, fake lashes, or press-ons—flies in the face of the patriarchal imperative to adhere to dominant beauty standards, without admitting they’re hard to maintain (see: the rise and fall of “the cool girl” archetype, and the thankless labor of no-makeup makeup).

In Stark’s case, harnessing the power of the corset to create extreme, body-morphing shapes signals the extreme effort required to appear effortless—and by embodying the oppressive forces of patriarchy to such an extent as to become undesirable by its standards, she achieves a sense of personal liberation and freedom. The corset may be an age-old symbol of the pressure to conform, yet in her hands, these qualities are deployed to new ends—reflecting back at us the ideals we’ve internalized, and demonstrating how far we still have to go.

Models Michaela Stark, Charlie Reynolds. Creative Direction Michaela Stark, Charlotte Rutherford. Hair Tasos Constantinou. Make-up Kevin Cordo. Set Design Tatyana Jinto Rutherston. CGI Metapoint.xyz. Photo Assistants Ed Aked, Georgia Williams. Hair Assistant Brixton Cowie. Retouching Nataly Trach, Ariel Brigmann.