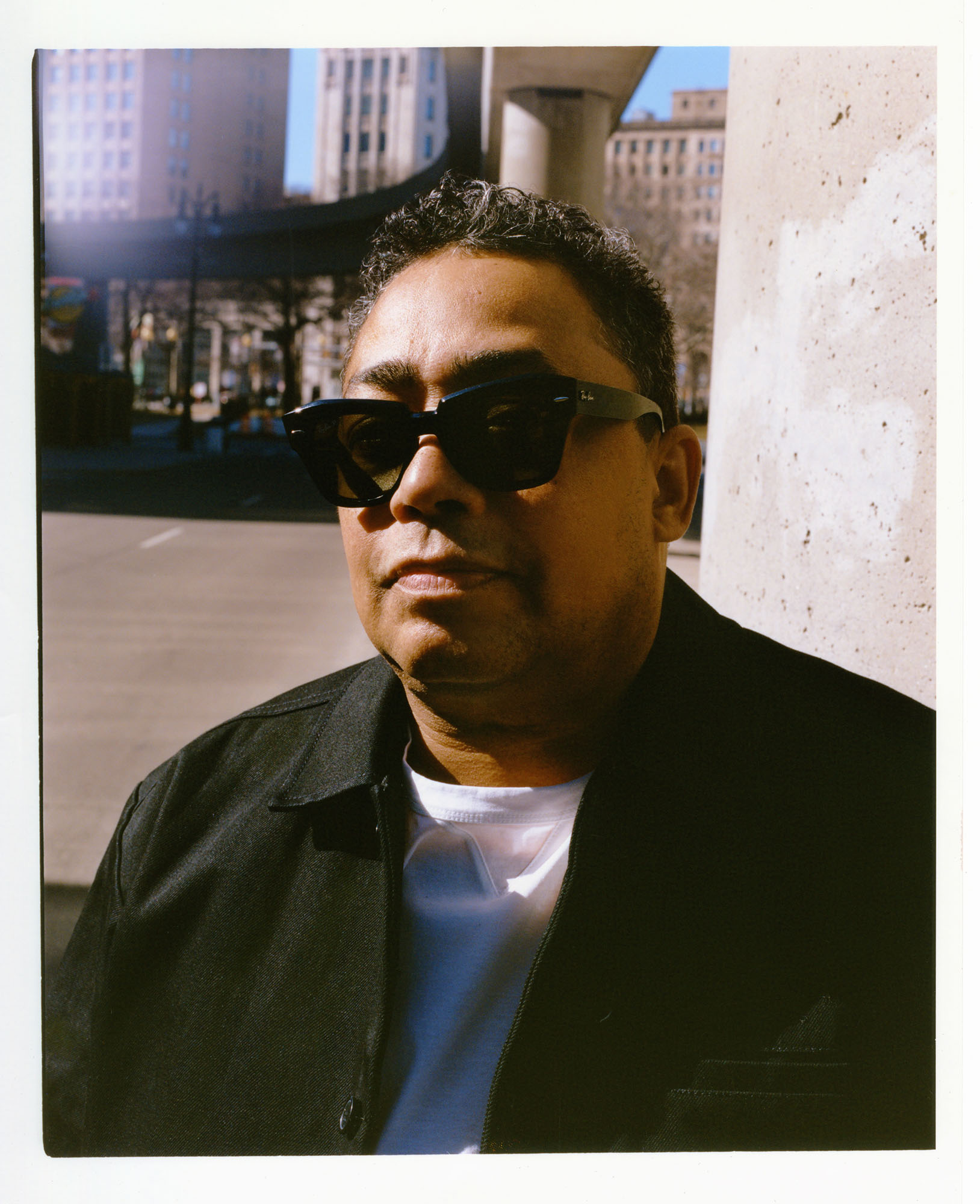

DJ Minx Selects: Techno Icons of Motor City’s Underground Sound, presented by Document Journal and Ray-Ban, chronicles the rich history of dance music in Detroit through the stories of five pioneering artists.

Chosen by DJ Minx for his selections and singular style of dance music, Delano Smith is a DJ and producer who has been a part of the story of Detroit techno from the very beginning. Smith is considered to be one of the first DJs to embrace the turntables and mixing. “I started in the early ’80s,” he recalled, “pre-house, pre-techno, during the disco era between the years of 1981 and 1984.” Taking a hiatus from ’85 to ’93, Smith would see the beginnings of techno as a Black and underground progressive music culture, and later reemerge as a DJ after The House Sound of Chicago and Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit spread the Midwestern American sounds worldwide. As a DJ he saw an opportunity to explore his own creative vision within his culture and community before setting his sights on sharing his sounds abroad: “I don’t know if they called it progressive music anywhere else, but in Detroit that’s what we called it. Progressive music fell under the umbrella of R&B…I don’t think post-disco was a term.” Smith imagined that a lot of synth-pop and funk music made by studio musicians would inspire techno, while older R&B and disco inspired Chicago house songs: “House music was very loop-based and used a lot of samples, but Detroit’s version of electronic music was more synth-based with Roland TR-909s, 808s, and a lot of the old Yamaha synthesizers. I think Detroit definitely took a different approach to dance music than Chicago did.”

Delano Smith first entered the Detroit music scene through parties that were thrown by Derrick May at Wayne State University, just as people were beginning to learn to use turntables and beatmatch. In those days, Juan Atkins had just begun releasing some of his first solo tracks as Model 500 after making waves with the hit song “Clear” in his band Cybotron. Smith described Atkins’ innovative sound as an abstraction of the sounds that were being played on college campuses and youth parties: “We were playing a lot of stuff that was out of New York, you know what I mean? Because that’s where all the music was coming from, like Prelude, Emergency. and those types of disco labels.” As Smith sharpened his DJing skills, he would join a record pool system where he’d receive promotional copies of unreleased music to test out on the dancefloor: “If you were fortunate enough or knew someone, they could get you in a record pool. In order to actually get in the pool, you had to prove that you had a DJ residency someplace.” Smith explained that he belonged to a regional record pool called DanceDetroit, but would also receive promos from another pool that was mainly R&B promos for Black DJs and clubs. “I was fortunate enough to have residencies at two clubs that everybody went to, to hear progressive music. A lot of the good records went to the gay DJs that were in the pool, and the gay scene back then in the early to mid-’80s was really, really strong here,” he recalled. “I was able to get into those groups around probably 1983, but all of the good stuff went to the bigger DJs like Ken Collier, who actually introduced mixing to Detroit.” Bridging the gap between the disco of the 1970s and the techno of the 1980s, parallel to the house music being created by Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy in Chicago in the mid-’80s, a cassette tape mix labeled “Ken Collier 82-83-84” would be one of the few documents of Collier’s pounding post-disco, proto-techno sound that would lay the groundwork for electronic dance music to come.

Delano Smith described DJing in the early ’80s as a hobby that was not particularly lucrative. Upon his reentry into dance music in the mid-’90s he found a fully erected global industry that allowed him a change of scenery and a chance to explore his own take on progressive music: “I went to a buddy of mine’s house and, you know, I saw he had turntables and records and stuff. I was like, ‘Oh yeah, I used to do this.’ I still had records, you know what I mean? I touched the turntables one time, and I was back in it and started buying records again.” Setting his mind on turning his hobby into a career, Smith honed his skills and soon played in New York, toured Europe, and attended the Winter Music Conference in Miami where he would live for a while. Establishing a singular style of mixing in the clubbing industry, he would start producing his own music in the late ’90s. “DJing now is a whole different thing. A lot of the big names have this whole machine working behind them now, and it’s a social media numbers game now, even with the festivals,” he said. “I don’t knock anybody for what they play or how they make their money or whatever. More power to you, but it’s a numbers and popularity beauty contest now.” Smith understands that the industry has changed as it has been financialized. “Techno and house have definitely been whitewashed, but this is the way things are. It’s a double-edged sword. If it hadn’t been whitewashed, it would still be way, way, way, way underground,” he pragmatically acknowledged, adding, “I’m not knocking Europe or Japan for embracing techno because they definitely aren’t buying shit here in America.”

When beginning to make his own tracks, Delano Smith experimented with the classic 808 and 909 drum machines that built the house and techno sound, though he wasn’t a trained musician. He strived to create his own sound, pulling together many elements of sounds that he felt could express who he was as a musician. “Techno is more of a feeling and the grit of the sound and the rhythm and the melodies that you create from samples and simple plucks of delays,” he articulated. “It’s a completely different deal than regular house music if you’re not a musician.” Techno, in the new millennium, became more stripped-down and precise following the release of Robert Hood’s Minimal Nation in 1994. Smith’s productions bear a similar compressed and decisive formula. He pressed his first track, “Tribunal of Souls,” on Psychostasia, a record label founded by Detroit native Reggie Dokes. The new minimal sound also brought new interest as the internet became more widely accessible: “Back in the day when I first started, I actually had to buy a friggin’ drum machine and a synthesizer. Now, you could just do everything with Ableton.” More recently, Berlin label Sushitech reissued Detroit Lost Tapes, a triple-vinyl collection of previously unheard tracks by Smith. “My sound is kind of a niche because it’s really kind of stripped back from a lot of other types of dance music, but it’s my take on techno and how I feel,” he stated. “My sound is more kind of a groove.”

Ray-Ban’s #YouAreOn campaign celebrates visionaries and authentic people who are true to their roots and themselves, and push the boundaries of creative expression for themselves and the world.

Shot in The Siren Hotel.