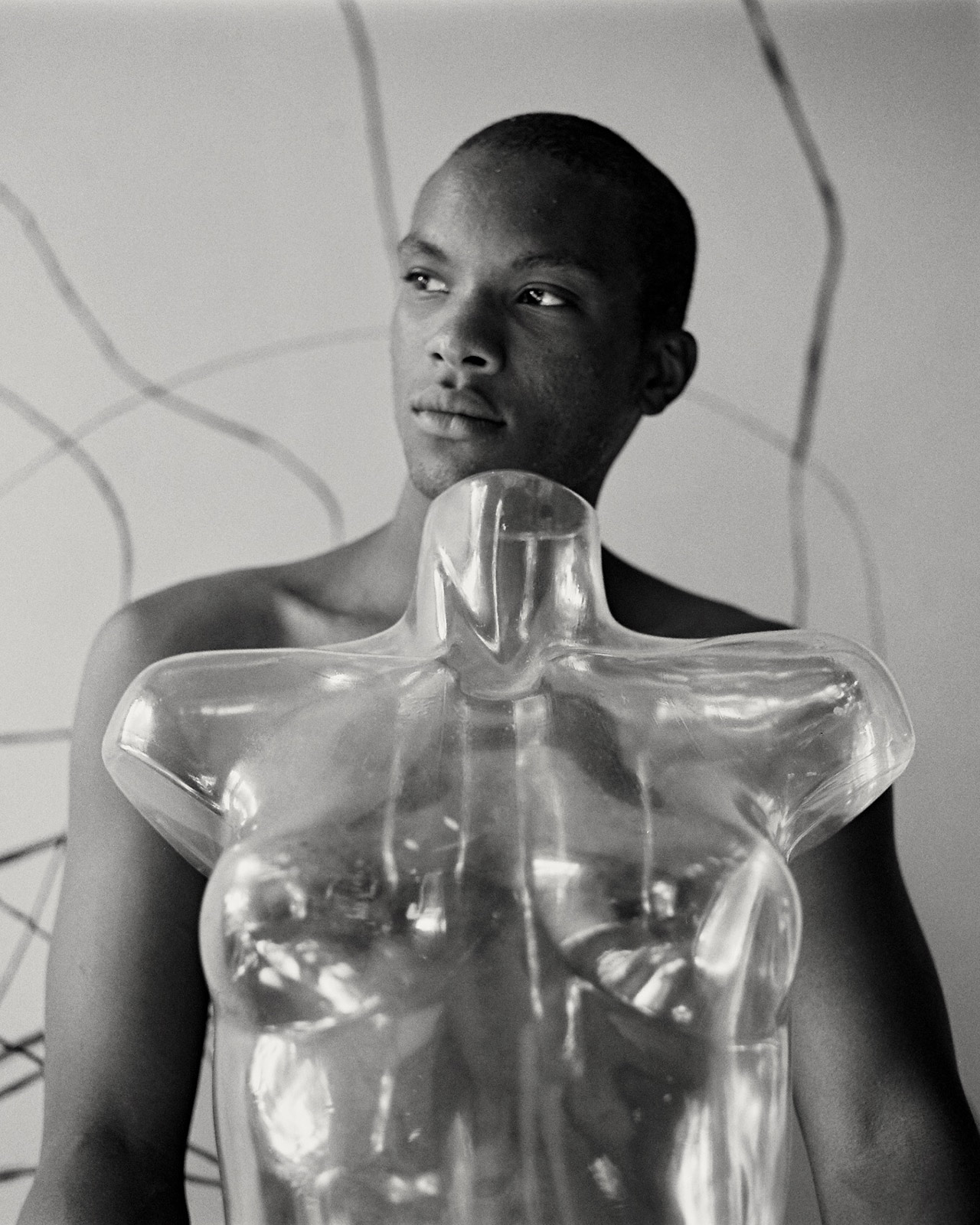

Kimberly Drew speaks to New York’s favorite SoulCycle instructor-turned-actor about his passion for social work and the importance of black, queer representation.

In New York, a city overflowing with unorthodox characters, Ross Days stands out as truly unique. Whether you’ve taken one of Days’s unforgettable SoulCycle classes, seen one of his comedy sets, or were lucky enough to witness his breakout performance in Jeremy O. Harris’s recent play, Black Exhibition, you’re left with the knowledge that you’ve encountered one of this city’s more special people.

Days, who has worked as a mental health coach, athletic trainer, and comedian, has had a windy path towards the limelight. A triple-fire sign born in Atlanta, but raised in Santa Monica, he always hungered for life as an entertainer but often felt stifled by a lack of representation of black, queer voices. In fact, it was not until a friend gifted the budding starlet with a suite of improv classes at UCB that he would take the leap on the stage. And, more, it would take Harris blind-casting Ross for him to play his first role in a production.

Recently, we connected post-therapy over small appetizers at the historic Union Square Café in Manhattan to discuss his life in New York, his recent role as a gender-defying Kathy Acker, and his hopes for the future.

Kimberly Drew: Let’s start with where you grew up and how you ended up in New York. Why do you find yourself here?

Ross Days: I was born in Atlanta, but I moved to LA when I was five and was raised there. I grew up in Santa Monica, and the demographics of the area are very Caucasian, but in a way, I was way less aware of my race growing up and much more of class because I was in really liberal neighborhoods. I went to this ‘call your teacher by their first name’ high school, where we learned about LGBTQ+ identity and community stuff. Then I went to college, and I studied philosophy, which was lucrative. You really do make money majoring in philosophy though. What did you major in?

Kimberly: Art history and African American Studies.

Ross: Glam, but you made it work immediately.

Kimberly: It was a mess. My parents were pissed but that’s a whole other story.

Ross: My parents didn’t really care for some reason. They were just like, ‘get a degree or we will disown you.’

So I went to college again at another liberal arts, white-but-mixed-also school. It was really weird because 50% of the student body were athletes, and I came from art school land, and I was like ‘oh! people actually go to the gym?’ That’s the irony of my job now [as a SoulCycle instructor]. Eventually, I got this job working as a mental health recovery coach with this kid. [His family] actually lived in New York, so they had me move to New York to continue working with him while he was in high school. It was really intense because [when] I moved to New York I was just thinking, everyone is rich and famous. This was 2012. It was the direct opposite of my life in LA. I was skateboarding on the beach and biking around, and then I moved here and everyone’s working aggressively. I actually didn’t really like the culture when I first moved here. I started working at SoulCycle, and right as I started, I decided I wanted to go to grad school for social work. I thought I wanted to be not a school counselor but a therapist.

Kimberly: Why?

Ross: Because I’d worked with recovering young addicts. I think I always liked working with youth and struggling children because [of] that kind of a rocky high school experience. So I got this [therapy] internship through school, and it was so hard. It was painful because I’d never seen black poverty before, just a simple basic need, not having food being a reality for someone. Just getting hints of why kids were really quote ‘bad’ or ‘dysfunctional’ in school because I was hearing from their mouths what was happening behind the scenes and how their parents neglected them or were in all of these really sad scenarios. I was just overwhelmed. I took it in too much, and all the while everyone was just [like], ‘you’re an artist. You are a performer. you need to do something with that.’ And I was like, ‘no, I want some job that you can easily point to and be [like] he’s successful.’

Kimberly: Did you start doing therapy work because it was a larger calling or service or was it something that you felt like you should be doing because you were good at it?

Ross: It was definitely both. I keep this letter that I got from one of the kids who I worked with at a rehab that says, ‘you’re the funniest person I’ve ever met. You make me happy. I’m just so happy to be around you.’ Not as if I didn’t have gifts of listening and offering guidance, but I felt like my joy or personality or humor was also what was lifting the kids up that I was working with.

For me, there was a feeling I needed to follow a white collar, normal job path because growing up in LA, I went to this school where a lot of the kids had parents that worked in the industry or were famous actors, and I wrote it [a career in acting] off because I feel in the black community, arts aren’t always the most supported career journey. It was kind of like no one nurtured that for me, because I do visual art as well, but [no one] was actually [saying], ‘go do that or go dance or go act or whatever.’ So I had this pressure because for all of my immediate family it was the norm to have a college degree. If you don’t, what have you done? It was kind of important for establishing a specific type of black identity, a black class. Even though creativity is my life, the fibers of my being, I kind of felt it wouldn’t be taken seriously.

Kimberly: So you were doing this therapeutic work, this really intensive act of care, but it started to wear on you. And so you had to transition out of that and find another way of existing in the city that’s already really hard. When did you start performing?

Ross: A friend of mine is an intuitive healer, she channels spirit guides, and she has clairvoyant skills or abilities. One day, after I had a tarot card reading where all these powerful cards were pulled—there was the high priestess, the emperor, some shit that—I was like, ‘what does the high priestess version mean?’ She was like, ‘hold on, let me check your spirit guides.’ Basically there was this rabbit hole of things, clues of things they were trying to bring to my attention. Then one of my friends bought me classes at UCB. They were like, ‘you need to start doing acting, comedy, anything performance-related because you’re going to have this immediate resistance towards it. You’re going to think the arts are something that are not going to be respected, [but] you’re going to have to get over that because this is going to make you a vessel for change for black LGBT youth and trans youth and all of these sorts of demographics, and I was like OK.

Kimberly: So you had this kind of divine reading that was like you need to be doing more with the skills that you have, even if it doesn’t feel quite right. It doesn’t pay the bills. It doesn’t serve me in these ways that I know and understand how to be successful. Did you start going to UCB; what was that like?

Ross: I hated it. I think in the beginning improv sucks because if the people you’re working with don’t get your humor, it’s kind of impossible to make it work. Also, I didn’t want to think that acting was possible. For some reason it felt really inaccessible and so I was like, I’ll do comedy because then it’s just me, I don’t have to rely on someone else. It was like crack. I think directing an audience to laughter was really satisfying to me. But it also freaked me out because I’m a wild card when I get a microphone.

Kimberly: It’s true. I’ve seen it. That’s your truth.

Ross: I literally have no filter. Like Pete Davidson told me I was a maniac, and I was like, ‘coming from you, homegirl, I don’t know how I feel about that.’ It was for a while starting to frustrate me, this feeling like I had no filter because I would get so excited to have this immediate platform that I didn’t know what I wanted to say. My mind would be bouncing all over the place. What I didn’t realize was I was craving some structure that I couldn’t find for myself or didn’t have a strong enough interest in comedy to [find]. I know things are changing in the media across the board, but if you go to open mics, it’s like straight guys talking about how women don’t have crushes on them, and it’s embarrassing, you know? I’m like, I have real shit to talk about.

Kimberly: You have these three pivotal Ross’s that, especially in the last seven years, have been brought to the fore. There’s like the therapeutic side of you who’s like doing private counseling, then there’s SoulCycle you, and then there’s also comedy you. How are you taking the reins with regards to who you want to be right now?

Ross: For an extroverted personality, I am just hanging back. Things are falling into place; I feel like I know now what kind of projects I don’t want to do in such a clear way that I don’t feel as with the wind as I was before. I think that became clear after this play [Black Exhibition]. I mean to jump from wanting to do acting since I was seven to being in a play that is confronting every aspect of my identity in a very public way and getting to perform this empowered person.

Kimberly: Tell me about the play, how that came about, and what character you’re playing.

Ross: I did a photoshoot with Jeremy [O. Harris]. Tommy Dorfman shot this thing for the Trevor Project, and I didn’t even talk the whole day cause I was really tired. I’d seen Slave Play, and I just really respected Jeremy and that play so much. It was one of the most challenging art pieces on race I’ve seen since the first time I saw Kara Walker. I was just in awe of him. So when I did that shoot, I was like, I’m gonna just be quiet.

Kimberly: Right. You’re like there’s a legend in the room.

Ross: Two months later, he just DMs me, ‘are you available for a play?’ And I was like, ‘yeah, yeah, yes.’ They were two days into rehearsals. I got thrust into it; I tell you that was the most stressful fucking two and a half weeks of my entire life. No girl, I rose up, and it was a lot. It was like a crash course in acting. I was like, this is weirdly the most liberating thing ever, to not be yourself on purpose. The role was a mind shift. I was playing Kathy Acker, who’s lesbian; I call her a violently sex-positive author. So I was playing a white lesbian, and I was just like, OK, gender has been removed from the play. It was just like such a weird perspective because the way she’s talking about what sounded like stereotypical gay sex, penetrative sex, but it was from this perspective of this lesbian woman.

Obviously it was stressful for me to learn the basics of acting, but at the same time, it was one of the most magical experiences ever because it was the first time I was working in an all queer, black environment, and pretty much every person involved with the play was a person of color. I didn’t have to code switch for like three weeks. But the interesting thing was, performing that intimate subject matter every night, I was getting emotionally affected by every day. Each character was kind of representing a different experience of black, queer existence and their relationship to their bodies or sex or whatever. To perform that in front of the theater demographics was really a trip.

Kimberly: I think a lot of what Jeremy does best as an artist is taking authentically black experiences and placing them in spaces that people don’t traditionally expect them to be seen. I wonder for you as an actor, embodying this character that is very untraditionally black and considering that to many Kathy Acker does not seemingly belong in a ‘theater space,’ what does it mean to show up every night and almost either invite or force people to participate in the understanding that this is theater?

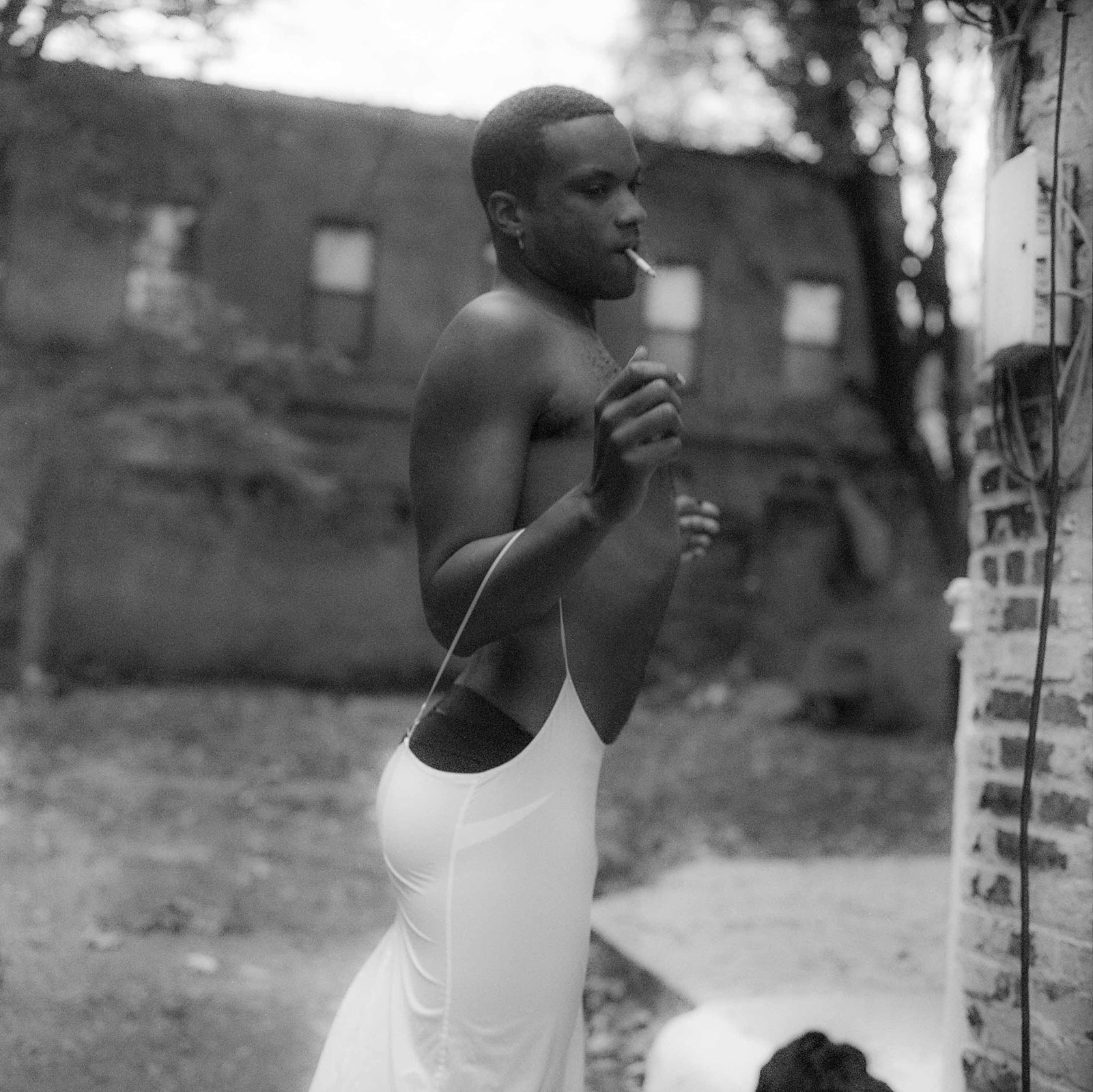

Ross: The most liberating experience in my life. I swear to God, I feel like I came out as more queer on the other end of that play because Jeremy was like put yourself into these roles. So to become this combination of like a white lesbian and my black-ass male body, it confronted this confusion for me; it kind of integrated parts of myself together because I was being this defiant, aggressive, powerful character in public in a way that is not always available to me in the streets. If I run around in a skirt, full beat, there’s going to be consequences. It was really liberating because I was this body, powerful as fuck, and I could directly yell at the audience through these words.

Kimberly: I came to your class like maybe a month before you got cast for the show and we were talking about post-Pride feelings, right? Everybody’s yay, I’m shitting rainbows. You were saying, ‘but no one’s talking about a lack of safety. No one’s talking about credible realities of what it means to be within this embodied experience.’

Ross: I went from zero to my name being mentioned in The New Yorker, being like I’m hilarious to yesterday someone being like, ‘I should have elbowed you in the face, faggot.’ That’s what I mean, it was so empowering to present in a way that is confrontational and know nothing bad is going to come of it. You really don’t get that unless you’re at a club.

The other day I was in a yellow fur coat and a striped dress, and I was just walking down the street clutching my coat, being like, am I safe? But I was like, I look so good, I don’t think I care. Fuck my safety bitch, look at this glam.

Kimberly: ‘Have you seen these mother fucking boots bitch?’ As a friend, I’ve witnessed you be so many people, and it’s beautiful to hear that you’re coming into this moment of more singularity. You’re in this process of like agency and world-building for yourself. It’s so funny talking to Jeremy, he’s like, ‘this bitch is the star of my show.’ I was like, ‘well actually what you’ve done is tapped into an energy that this person’s radiating off.’ And like you didn’t even fucking read [for an audition], like that’s the most raw story ever.

Ross: I didn’t talk the full day that I met him.

Kimberly: I also don’t believe that for a second.

Ross: You look into my eyes girl. Trust and believe, I was sitting in the backseat of cars like, ‘damn, that’s a genius.’ When I say to you that my loud ass was quiet that whole day—

Kimberly: Wait, so you were acting, that’s what it was!

Ross: Yes! Girl, that was my first role: sitting quiet in the backseat of a car with other people [laughs]. But I think the play set my career goals so much higher. Because when I was secretly in the corner like, ‘I want to be an actress!’ I was like already settling for a side character token gay role. I was talking to someone about being represented yesterday and they were like, ‘what do you want?’ And I was like, ‘well I want to play roles about people that look, talk, and dress like me and who actually have depth.’ I’m not twerking in the background of some lead character. I’m like, no bitch you will see me, you will know that I exist.

It’s not for my own vanity, it’s for the fucking kids who I had to work with, to show them that we’re not using the word faggot. You saw a quote ‘faggot’ on TV and you loved him. But I feel without authentic representation of my genre of humanity, nothing happens. I think the media is one of the most powerful social tools. Media can change the temperature of society really quickly, and I think Pose existing has done a lot. Do you watch Sex Education? I was watching it, and I got so emotional. Just to see a young, black, gay or queer kid, such as Eric. She’s very come into her skin with the little purple eyeliner. I feel like the tide’s changing.

Kimberly: So what are you trying to do now?

Ross: I want my career to elevate me into a very large place so I can have the most visibility to do advocacy and activism for black, queer youth. The only reason why I want to be a famous actress is so I can build up centers for young LGBT youth to help them find an education so that they don’t keep ending up in the same cycle. I mean I don’t want to sit around and wait for somebody else to do it, you know? I mean I want an Oscar, I want—Tiffany Haddish we’re going to do a buddy cop movie together, we in this bitch. I want to play roles that are authentic to the experiences of people like me and don’t shy away from words that are dark about it or the joy. I think either it’s complete entertainment or the sadness of the trauma of our lives, you know? I’m already working on writing projects with that concept. It’s interesting thinking about not only your own lived experience but then also tapping into other people’s lived experiences firsthand, how many more stories need to be told. I want a production company because I think there’s so much being made that’s not being greenlit. I’m trying to pull a Rihanna, okay? I’m going to give you eight albums of glory, and I’m going to change the world.