During the exhibition’s final days at the Brooklyn Museum, writer and philosopher FT wonders: Can institutions handle zines?

There’s an old zine by Henry Rollins that I keep in my home library. I didn’t buy it, and I’m not a Henry Rollins fan; it was given to me many years ago by a friend who got it in LA in the ’80s or ’90s, then gave it to me when I was an undergraduate in Berlin. That’s why I still have it, 20-plus years later, in New York: it means something to me because of where I got it, and how I got it, and when I got it; it represents the little niche world I was involved in at the time. Its value to me is exclusively sentimental, and cannot be transmitted—though, as it happens, I saw a copy of that same zine on sale at MoMA PS1 for $250 not long ago. Meanwhile, the Brooklyn Museum’s current show Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, one of the largest exhibitions on the topic to date, is currently in its last month. Exceptional and enormous, it features room after packed room full of astounding windows into a dazzling array of microcultures.

Museums are most often reserved for objects that are both art and commodity. Hanging on the wall in front of you, the museum object implies at least two things: that the aesthetic-cultural value expressed transcends the time and place of its making, being in some way transhistorical or universal or at least translatable over the ages, and that the value of the thing is enduring enough to justify the acquisitions department’s line-budget item. This doesn’t mean the market value of a commodity can’t change or crash, but when a museum purchases an object, it assumes the object’s value will either remain or increase along with its aesthetic or cultural appeal. This is one fundamental difference, incidentally, between a museum and an archive. Archives often collect things that otherwise would not be of value to anyone, and, if anything, would otherwise look more and more like junk with every passing year.

A zine, by these measures, has no place in a museum. In its natural habitat, it fulfills neither of our conditions. Before the internet completely transformed how things are commodified and distributed, zines were made by and for a particular subculture or social network, and circulated primarily within that subculture and social network. The content, iconography, and references of a zine are often inscrutable to outsiders; the imagery and aesthetics of the zine are often counter-hegemonic or deliberately “anti-professional,” making them look busy, confusing, and even offensive to a more normative eyeball. And while a zine is often a “commodity” in the sense that you can buy and sell them, by intent and design their value is fungible: you don’t buy a zine because you think it will appreciate in value; you buy a zine because your friend’s band is trying to fix their van, or because nobody else in your little town cares about lesbian vampires or trade unions in ’70s Wisconsin. Generally small and made of the cheapest materials available, zines lose both meaning and value as the historical moment of their creation drifts away. Putting zines in a museum seems to make demands of them that their very nature might resist.

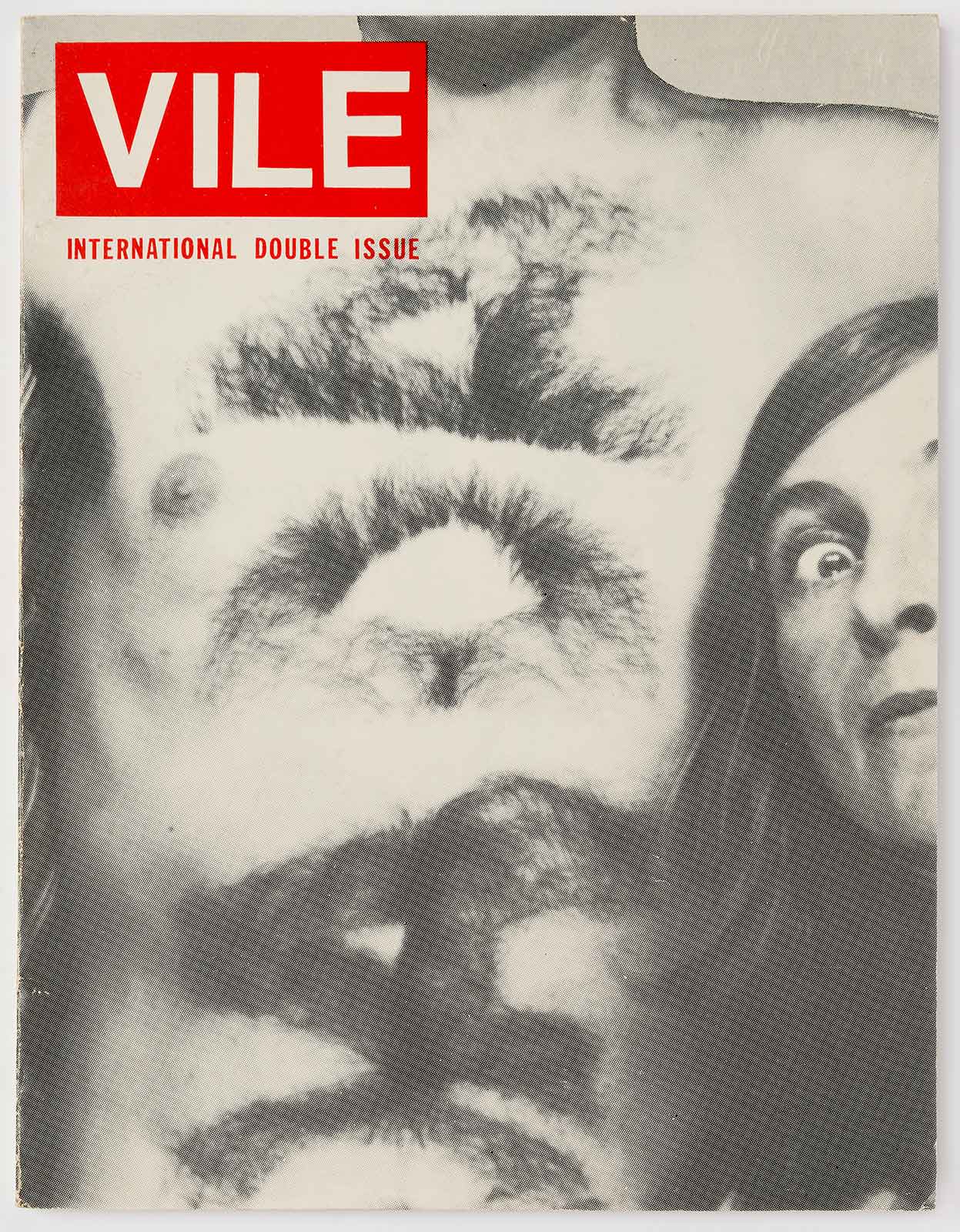

Found in display case after display case and hanging on the wall in manifold rows, is a tiny fraction of the vast output that falls under the museum’s rubric of “zine”:

“A zine, short for fanzine…is generally defined as a quickly produced, low-cost publication intended for relatively limited distribution…The word zine and the zine’s typical form gained popularity with the availability of affordable reproduction technologies.”

Indeed, the span of time the show covers parallels the rise and popularity of two fundamental technologies: the mimeograph machine and the photocopier. With a rich history to draw on, the selection and preparation process for the show took nearly five years, and required some deliberate limitations. “In addition to focusing on North America,” says Drew Sawyer, one of the exhibition’s curators, “we set other parameters to help limit the scope and selection. For example, we only included publications that were called ‘zines’ or ‘fanzines’ at the time of their making, either by the maker or by contemporary readers. So we did not reclaim publications that from today’s perspective could be considered zines in hindsight.”

The range of the exhibit is fantastic, and almost every object in the show was made for a specific scene or subculture with its own iconography, slang, and hyperlocalized values, including a number of niches you’ve probably never heard of. Copy Machine Manifestos is a relatively unique occurrence in the art world: a hit exhibition that showcases the work of many, many lesser-known names instead of just a few enormous ones. But that unique opportunity is tempered by the lingering sense that these things are maybe just not supposed to be here.

“Zines are meant to be passed around amongst the people,” says Neta Bomani, whose work is featured in the show. Bomani describes herself as a zine maker, not an artist; she’s the co-organizer of the upcoming Black Zine Fair with author and activist Mariame Kaba, with whom she also co-founded Sojourners for Justice Press. “There’s always been a tension between the underground and aboveground when it comes to zines or any other radical form of publishing. Curators of zines have an ethical responsibility to the ‘artists’ or zine makers whose work is in the exhibition…What does it mean to take something that costs $5 or $15 and embed it in a network of highly expensive and fetishized art commodities? Curators should understand the politics and the weapons of the art world and how that connects to larger systems that enact structural violence.”

Over the course of the 21st century, there’s been a distinct movement in museum curation away from best-known masterpieces and towards ephemera: notebooks, drafts, juvenilia, but also objects from the artist’s life that give their work an extra dimension of humanity. In part that process is economic: with the price of masterworks, the number of investment collectors, and the number of art history PhDs all escalating dramatically in just a couple of decades, a lot of the institutions and curators below the very top tier will inevitably be left working with scraps. But in part, this shift is also cultural: today’s millennial curators grew up on Tumblr where finding aesthetic and intellectual value in otherwise-overlooked objects was the platform’s primary virtue (Bomani also grew interested in zines through Tumblr). Now the transvaluation of ephemera takes the next logical step, from accompanying the exhibit to being the exhibit.

Indeed, the great innovation of online—to make available vast amounts of information, imagery, and content otherwise difficult to access or acquire—here seems brought to three-dimensional life. Moving through the show feels like a miraculous opportunity to see objects that by all rights should have ended up in a trash heap before I was born. But it also feels slightly voyeuristic, even invasive, to know that day after day a “general audience” parades in front of the intimate secrets of countless tiny groups. Sure, there are some erect penises and discussions of drug use I identify with pretty easily, but much of this material truly just was not made for me, or for people like me. I wondered how many of the zine makers had died in poverty while waiting for a big break in the art world or other institutional forms of culture production. I wondered how many died of AIDS. I wondered how many died of COVID. I asked Sawyer what protocol or ethos curators should follow when putting a niche community’s cultural products on display for a larger audience. “Many objects in museums were made for specific communities or even individuals,” he explained, “so this issue is not unique to zines or any of their associated subcultures. From the beginning, we decided we would only include zines whose makers (or their estates) gave consent to being included in the show—something that is not actually required when borrowing objects from museums or libraries.”

The show’s subtitle suggests the exhibition is explicitly about zines made by artists, but “art” is not just a kind of making; it’s also a set of professional, economic, and institutional delineations, many of which exist solely to exclude the kind of people who make zines. For every zine by a young rebel who later found a place of some kind in the world of institutional culture—Bruce LaBruce, Vaginal Davis, Kathleen Hannah—there are several by people who would not have identified or recognized themselves as artists, and whose primary concerns may have been information exchange, personal expression, or collective liberation. “While I personally don’t know what an ‘artist zine’ is,” Bomani states, “I think it has everything to do with distinguishing and legitimizing the work of a subculture of people who have historically rejected the very notion.” Among the crucial forerunners of late 20th century zine culture were the “little magazines” of the Harlem Renaissance; like a number of the zines in the show, these earlier publications were not an explicit counter-statement to institutional culture—they were simply not in dialogue with it at all. “Making zines is also about connecting with my history as a Black person born and raised in America,” she notes. “There’s a whole history of zines that isn’t told within the subculture.”

Lined up row after row behind glass vitrines, the object becomes flat and immobile. I may not need to touch David Bowie’s jacket for it to add texture to an exhibition about his life, but a zine is normally a much more tactile and fluid experience: flipping through it is part of the experience, finding that one page corner or half-hidden image that speaks to you in a strange but somehow familiar language. Oddly missing from the show was the dynamism and exchange that generally accompanies zines. While commercial value doesn’t necessarily preclude a sentimental one, the necessities of preservation and the contingencies of “intellectual property” can often preclude any future personal bonding with these objects, just as their accumulation precludes future circulation. Major art and cultural institutions have not always responded successfully to the political realities of the present moment; the preservation of niche and subcultural artifacts in alignment with the ethos of the institution might not necessarily align with the needs and values of the groups whose production is being institutionalized.

“Zines belong in community,” Bomani concludes. “At zine fairs, in back pockets, under coffee mugs with stains and dog ears on them, at your friend’s house, in anarchist bookstores, at noise shows, at raves. In this existential time where cultural and digital preservation is and should be a concern, we also have to recognize the duality and accept that our zines aren’t meant to be here forever.”

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines is on view at Brooklyn Museum through March 31.