The Scottish artist brought a new romance to painting when he came of age in the ’80s. Many years and broken auction records later, those early works will finally be seen again. The artist speaks in Document's Spring/Summer 2014 issue.

In his three-decades-long career, Peter Doig has established himself as one of the most inventive and accomplished artists working in painting today. First earning international critical recognition in the early ’90s, Doig reshaped the discourse of painting at a time when many artists and critical thinkers preoccupied themselves with rumors of its death. Created shortly after the artist settled in London, these early works—which will be exhibited at Michael Werner Gallery, London, from March 20—show the young artist mining new and varied sources for inspiration and experimenting with a range of techniques. Then, as now, his singular approach to painting reimagines the medium’s transportive ability to conjure meaning and mystery.

Parinaz Mogadassi: These works were made when you were in your twenties. Can you tell me the context in which they were made? Would you consider it student work or not?

Peter Doig: They were made while I was in my last year at Central Saint Martins and over the next seven years, prior to returning to college in ’89. I guess some are student works, but most were made in the studio that I had after leaving Saint Martins.

Parinaz: Saint Martins in the early eighties was a hotbed for not only art but fashion as well. Do you think the convergence of those two worlds in a student environment had an impact on your work? Do you think you would have developed into a different type of painter if you had gone to one of the other London art schools at the time, like, say, Goldsmiths?

Peter: Saint Martins was certainly very different than all the other art schools. We had a very strong fashion school and also a cutting- edge graphics department. A lot of us mixed and went out together. Robin Derrick was designing the early issues of i-D as a student and the likes of John Galliano and Stephen Linard were making strong statements in the fashion department. But Saint Martins was also strongly connected with all that was happening in the London club scene of the late seventies and early eighties. We would all go out a lot. Some painting students would bring clothes to go out in, and hang them in their studio. Chris Sullivan, who ran Hell and the Wag Club, was also in the fashion department. The excitement generated by this world inside and outside of college definitely had an impact on the work we made. In ’80 there were probably only 200 or 300 “new romantics” in the world, and all were in London. The scene centered around the Blitz Club, Hell, Saint Moritz, 21 Club and lots of other small one-nighters. We had a strong contingent of some of the most interesting people, and the likes of Boy George—this was way before Culture Club—would hang out at Saint Martins, even though they were not actually students there.

“The excitement generated by this world inside and outside of college definitely had an impact on the work we made. In ’80 there were probably only 200 or 300 “new romantics” in the world, and all were in London.”

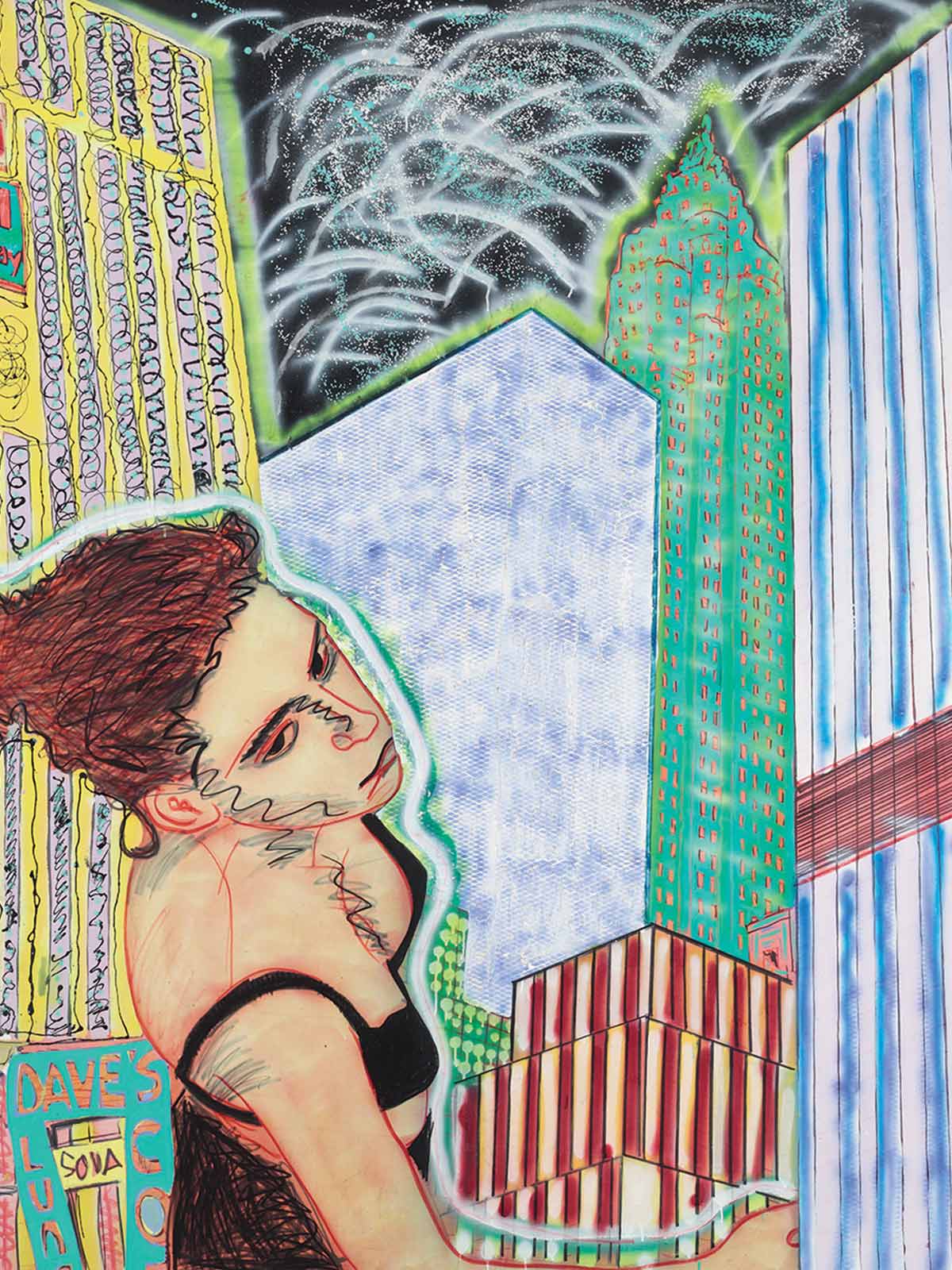

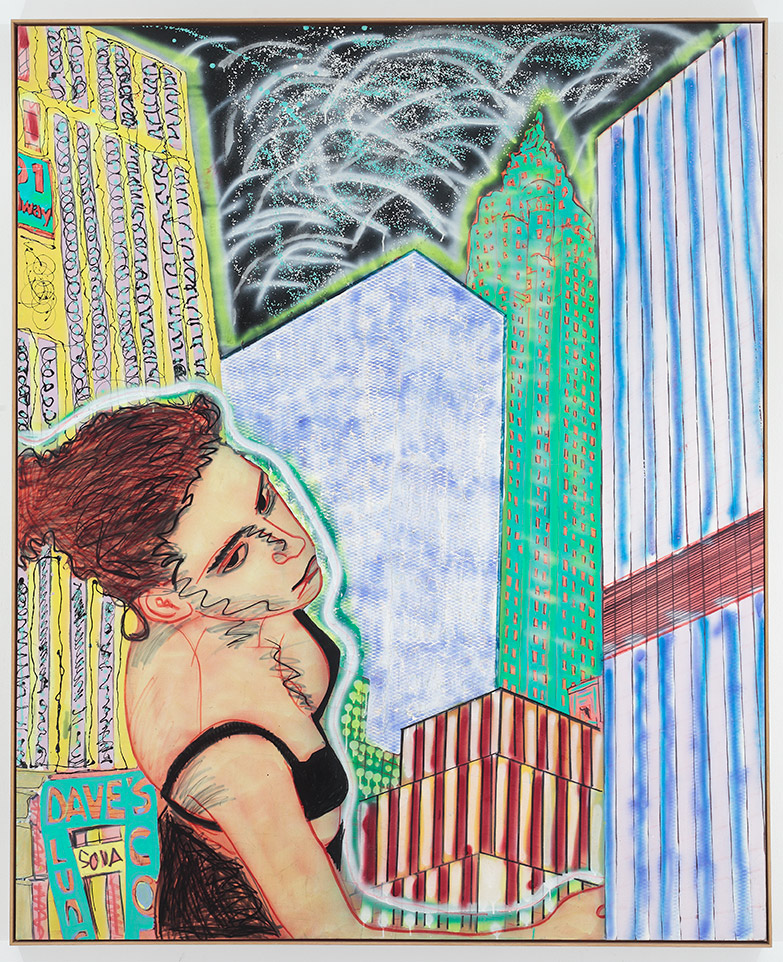

Parinaz: Your imagery from that period is charged with a manic energy that is almost impossible to replicate outside the confines of youth. It’s interesting what you say about club culture, as there is direct evidence of it in your work. We see Leigh Bowery taking the form of Burger King, and exotic dancers straddling your canvases. In terms of imagery, were you pulling from your own life? From your travels?

Peter: Actually I didn’t meet Leigh Bowery until after I had painted Burger King, but he identified with it because he had once almost become a manager of a Burger King. The imagery for that painting came partly from a dream and partly from visiting New York City in the early eighties. The scale of the huge heads advertising KFC and other brands in the Times Square billboards was, possibly, unique in the world at that time.

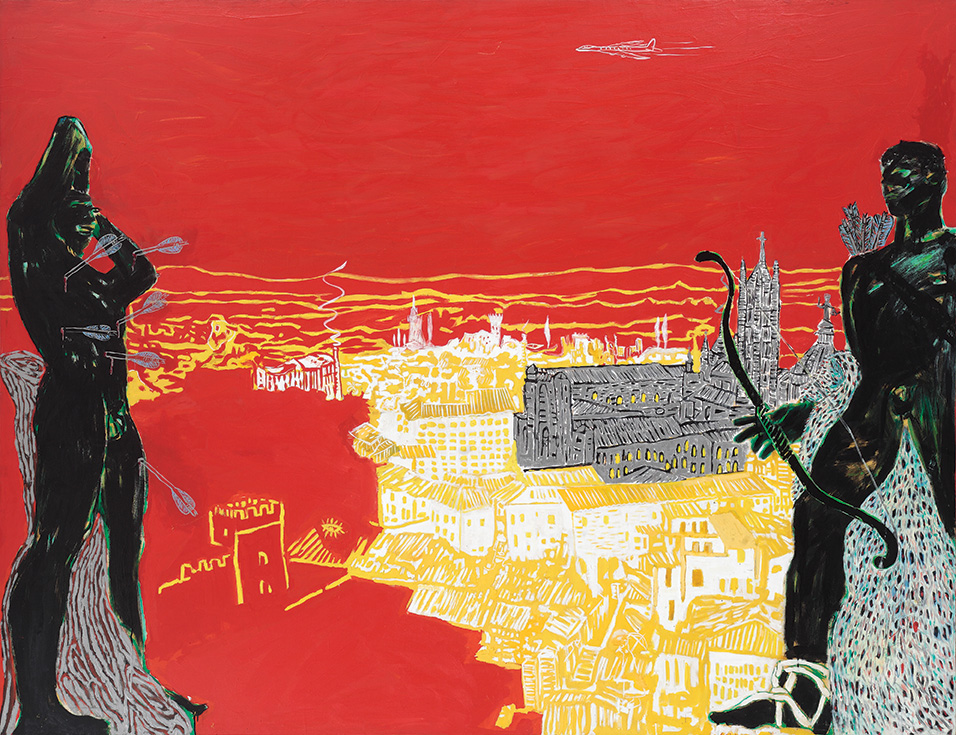

Parinaz: Your crosshatching of cities is intriguing. We see Siena and London occupy the same picture, we seem to weave between Berlin and Montreal. And then there is the American terrain, from New York City to cowboy country. How do you account for all of this?

Peter: My work was influenced by my travels, and also where I hoped to travel. Rome and its ancient world mixed with the con- temporary one we occupy. Back then you had to actually visit places to see things. The cowboy stuff was related to my own past (having worked in the Canadian west). Also when I visited New York City for the first time, I could not help but think of Midnight Cowboy.

Parinaz: In the pre-Internet era, when visual information was not so readily available, would you say that the act of physically seeing was more important than it is now? You often cite two key exhibitions you saw while studying at Saint Martins, Who Chicago? and A New Spirit in Painting, as formative. To what extent do you think the experience of seeing these exhibitions had an influence on your work?

Peter: I think it was an era of discovering things for yourself. So as an artist, one could search out imagery or source material via second-hand bookshops or by other means—one had more a sense of ownership because no one else would have access to the same source material as readily. And people could get quite possessive about their discoveries. I hadn’t yet encountered some of the artists included in the two exhibitions you mentioned—but more importantly the shows also contained types of painting that I hadn’t seen before, and subjects I hadn’t yet seen in art. The impact was thrilling and daunting. It created an ambition in us to make large works and not be afraid to use subjects from outside what was, for the most part, considered suitable for art.

Parinaz: Your scale and your commitment to a personal vision in the work is noteworthy. You weren’t afraid to go out on a limb. So of- ten now, young artists make work that is designed to fit an aesthetic or satisfy trends in the market. It’s a shame, because the beginning of a career should be a time for experimentation. In addition to being an artist, you have taught in art schools for the past 20 or so years.

Peter: Well I do think it’s a shame to see young artists just jump on market trends, no matter how seemingly cutting edge the trends are.

This article originally appeared in Document’s Spring/Summer 2014 issue.