For the second installment of Document’s series, SculptureCenter’s Jovanna Venegas considers the archive as “both a physical record and a living concept”

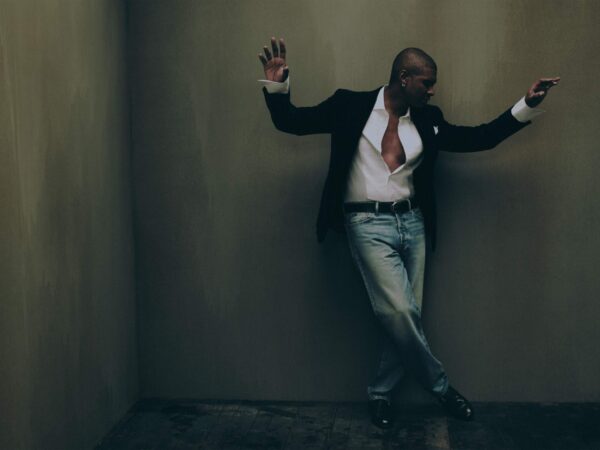

How can an archive be both a record of its time and a living organism shaped by its histories? In an era when contemporary culture tends to privilege immediacy, the archive offers resistance by inviting slowness, friction, and a longer view. In this three-part series, Document turns to curators Ruba Katrib, Jovanna Venegas, and Drew Sawyer, photographed on location, wearing Vowels, the brand that finds its own voice through archival research. Each of these curators places the archive at the center of their practice. Whether rooted in institutional holdings, collective memory, or ephemeral traces, their work reflects a broader shift in curatorial thinking: one that treats the past as a fragile and potent tool, open to reinterpretation.

For Jovanna Venegas, Curator at SculptureCenter and former Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at SFMOMA, a single poem, even a conversation or an object, can trigger a quest of curatorial research spanning continents and disciplines. Her introduction to archival practice began at home. At her parents’ photo studio in Tijuana, her mother kept a 30-year chronicle of the city’s social life. This early encounter with collective memory shaped Venegas’s curatorial sensibility, attuned to the ways artists preserve, embody, or reimagine their own histories. Across projects with figures like Luana Vitra, ASMA, and Pat Oleszko, she approaches the archive as a generative process where knowledge moves through bodies, places, and gestures.

Venegas’s curatorial methodology thrives on curiosity and encounter. From Afro-Brazilian spiritual traditions to postwar avant-garde dollmaking, at SculptureCenter, she cultivates a space for commissioning new work that privileges vulnerability and risk over certainty. Her exhibitions balance rigorous inquiry with visual seduction, drawing viewers in through affect and atmosphere. For Venegas, the archive’s vitality lies in this tension between preservation and transformation, method and intuition, body and text. Her work expands the field of art’s memory by opening it to new ways of feeling and being seen.

What does “the archive” mean to you—not just in theory, but in practice?

For me, the archive is both a physical record and a living concept. For example, we are working on an exhibition and catalogue with the performance artist Pat Oleszko. On our first studio visit, we saw her personal archive: a meticulous, chronological record of her work that she has been cataloguing since the late 1960s, including every review, photograph, poster, invitation letter and much, much more. This archive is a testament to her work and life in art, which to me raises questions about permanence for many artists working today. How are they preserving their own histories? If they don’t do it, who will?

On the other hand, I recently heard from the artist Umico Niwa how she considers her recent organic installations Memory Palaces—as archives not of documents, but of embodied experiences. The body itself becomes an archive. So in practice, I value methodical archives for the glimpse they provide into the past, but I also see them as something we actively carry and reinterpret.

How do you typically begin a new research-driven project? What leads you in?

It can vary from a conversation with an artist, an artwork, a poem, a news article—and from there I go down a series of rabbit holes. It’s exciting because at SculptureCenter I get to work with artists from many different regions and backgrounds, and that sometimes means I have to dig deep into areas I am not familiar with.

For a recent project with the artist Luana Vitra, who is based in Minas Gerais, Brazil, I felt I had to know more about the history and social and religious practices of the place to better understand her context. So I went to visit her and also did a lot of research around Afro-Brazilian cultural forms. But then with a project I worked on with the Mexico City-based duo ASMA, they made a series of handmade dolls, and they were thinking more about the subconscious and the history of dolls within the post-war avant garde, so I went down that research path to better understand the work. For a group exhibition I just opened, it started with a text-based artwork and poem an artist wrote that sparked a series of threads. I feel like the most exciting part of curatorial work is getting to go down many research paths.

Do you see your work as rewriting history, or simply rereading it?

I see it as expanding or widening views on history, rather than rewriting or rereading it. History is a messy, subjective, and interconnected tapestry. I try to consider a multiplicity of voices and experiences and how they might overlap.

How do you approach curating artists or subjects whose legacies were overlooked, erased, or marginalized?

When thinking about this within the context of exhibition-making, I think it’s important to study the work and the material and spend as much time with the practice as possible. From there, for me it is about giving the work its due space, and providing contexts and invitations—an opening for visitors to be able to approach the work.

How do you think about visual pleasure in the context of research-driven shows?

To me this is extremely important, and I think about it for all of the projects I work on.

There’s nothing I love more in an exhibition than being drawn into the work, the practice, or the space through the body. I like to be seduced. I think a lot about affect and pleasure, about being drawn into a small universe. To me, that happens through the environment we create with artists to give an opening to their work for the visitors.

One of the last exhibitions I worked on at SFMOMA was Sitting on Chrome, which I co-curated with a few colleagues and the artists Guadalupe Rosales, rafa esparza, and Mario Ayala. It was about the influence of lowrider car culture on their work. Through a series of commissions we did, from the moment you stepped into the space the intention was that the public would feel the sensation of going on a car ride. And with ASMA, we wanted to create an environment for the dolls to live in.

How do you decide what not to include?

Editing is crucial. I consider the visitor’s experience and try to remove anything that might divert from the exhibition’s narrative or fail to serve the artist’s practice. In to ignite our skin, a recent group show, I included only ten artists so that each could take up space effectively and to be able to give more resources to each. I question the value of recent mega-biennials with hundreds of artists. I often feel it does not serve the artist nor the viewer.

Was there a formative experience that shaped your interest in archival work?

The archive that came from my parents’ photo studio in Tijuana was my formative introduction to the concept. From the late 1970s, they documented the city’s social life—weddings, school groups, political figures, and more through photography and forms of self-representation by the sitter. My mother meticulously organized and labeled every negative, creating a 30-year portrait of Tijuana. I find this city archive incredibly inspiring. Now, my sister Yvonne Venegas who is an artist, has been digitizing and exhibiting it, is becoming the next keeper of this memory.

How has your relationship to institutional frameworks—museums, collections, academia—evolved over time?

I have learned that institutions which seem rigid can actually be hacked—there are slippages you can move through, and I find that exciting. While I believe institutions should be more nimble and less rigid, it’s also possible to work within the cracks and edges and will projects into being while that change happens.

How do you protect space for curiosity and experimentation?

One of the things that I love most about working at SculptureCenter is that we primarily commission new work by artists. This means that once we start working together, they submit a proposal and, as a small institution, we work closely with them, often the full team from me to our exhibition manager to our head installer, to realize the project.

And this space of commissioning feels like that protected space. Both artist and curator and institution must be vulnerable and try something that has potentially not been done before. Instead of questioning the artist, we should support and protect that space of creation as much as possible.

Vowels, the made-in-Japan designer label operating between Tokyo and New York, grounds its design philosophy in rigorous archival research. Creative Director Yuki Yagi formalized this commitment by transforming the brand’s New York flagship into an active site of inquiry—a hybrid space that functions as both retail environment and living research center. Central to this vision is the brand’s “research library,” a curated collection of books, periodicals, and printed ephemera that inform and contextualize Yagi’s creative output.