In 'Black Rabbit' and beyond, the actor anchors the storm, proving that longevity is built not on looks but on discipline, pattern, and craft

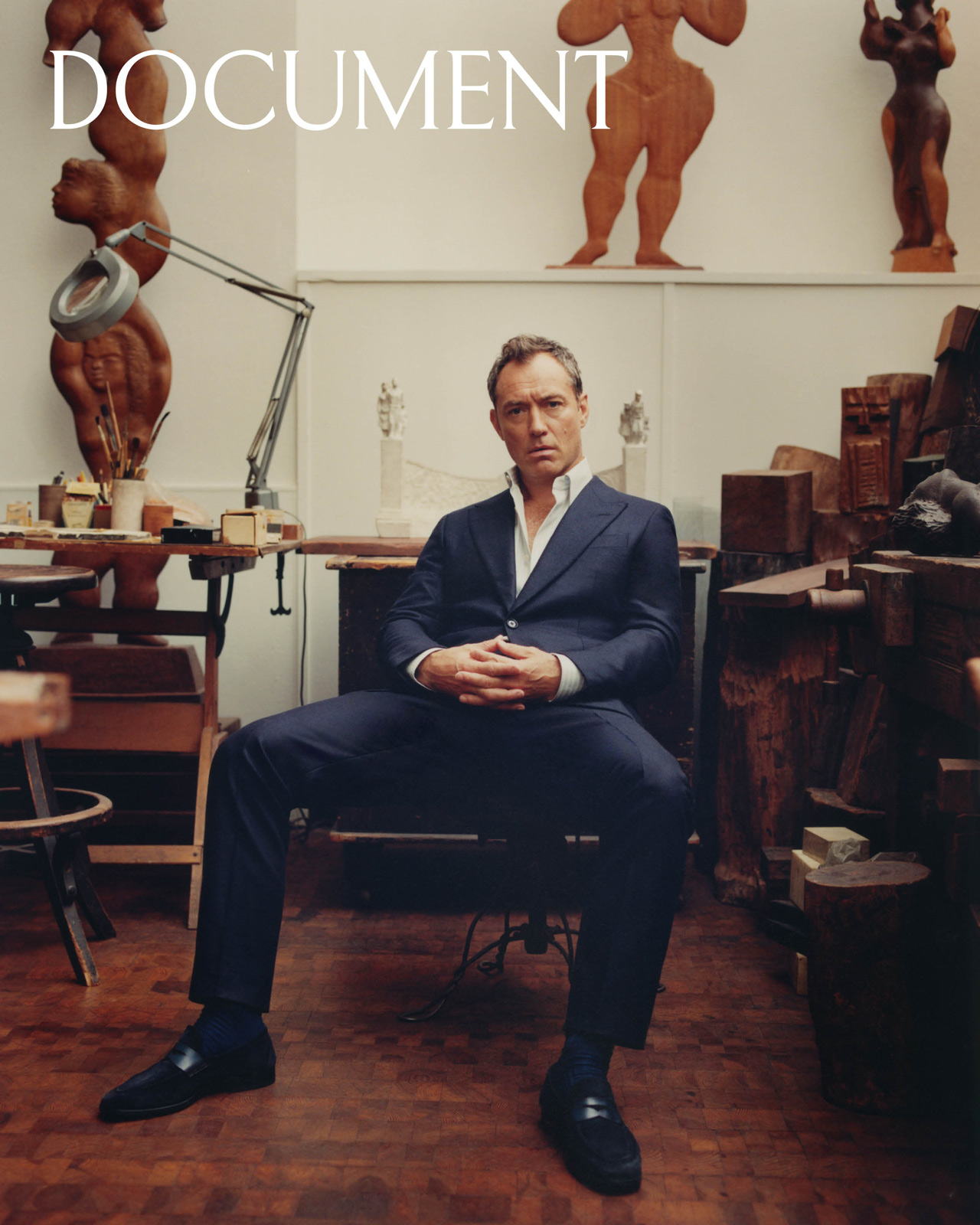

In a Manhattan hotel room, Jude Law, dressed in loose sweatpants, a tank top and robe, radiates vigor—as if he’s just burst through a stage door and is ready for his big monologue. In 2009 he held Broadway rapt as Shakespeare’s Prince of Denmark, fueled with impotent rage at Elsinore’s stench of corruption. “If vigor were all in acting Shakespeare, Jude Law would be a gold medal Hamlet,” wrote Ben Brantley in the New York Times.” I’ve always loved that energy, the sense that Law is coiled, ready to spring, a quality that suffuses his best performances, often to the point of self-destruction. It’s there, too, in Jake Friedken, the character he plays with scorching intensity in Black Rabbit, a new series now streaming on Netflix.

It’s early evening, and Law has just flown in from Paris, a dash that sounds like a stunt until you hear how matter-of-factly he renders it: “I left at about 5am, drove to Paris, flew to New York, hit the ground running late because the flight was delayed by heavy winds. And then we work tomorrow, and I return tomorrow night.” He smiles when I suggest he looks disarmingly fresh. “Kind of. And it’s still exciting.” Then, almost as an aside, he lets you glimpse the philosophy that keeps him buoyant. “Well, part of that is: am I drowning or am I waving? That energy is a survival technique. It’s not quite making the best out of a bad thing, more like, ‘I don’t see any other options.’ I can’t suddenly reinvent myself or go off and learn to do something else. This is something I love and enjoy.”

If Law was once the poster boy for a certain brand of youthful, turn-of-the-century glamour, the 52-year-old sitting across from me is animated by something tougher and more practical: conviction about the work, vigilance over the story, and a restless appetite for risk that avoids being typecast. “There’s a lot to be exuberant about,” he adds, and then explains how producing Black Rabbit changed his relationship to the machine. “Doing this kind of interview is different now, with a producer’s hat on, because I also have a real belief in the collaboration—the work as a whole, with all these other folk who I feel I’m supporting, and having seen the work come to life from an idea that was shared between [show creators] Zach Baylin and Kate Susman and myself. It’s very different to just sort of, ‘So, they hired you to be in it. What do you think?’ It’s a different kind of relationship. You’re a lot more hands on.”

“Well, part of that is: am I drowning or am I waving? That energy is a survival technique. It’s not quite making the best out of a bad thing, more like, ‘I don’t see any other options.'”

Black Rabbit opens like a bruised hymn to Brooklyn ambition gone bad—two brothers, one restaurant, and a dream assembled from denial and nerve. Jason Bateman, who also directs the early episodes, plays Vince, a schemer with debts and charm; Law is Jake, the brother who actually keeps the lights on and, as it turns out, the secrets. The Black Rabbit—already on the verge of becoming New York’s next big thing—shudders when a hostess (Abbey Lee) is assaulted, and suddenly the show’s moral weather shifts: loyalty collides with opportunism; private shame metastasizes into public crisis. Around the Friedkens hum a ring of strivers and survivors (Amaka Okafor’s Roxie in the kitchen; Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù’s Wes, a musician bankrolling the venture; and Cleopatra Coleman’s Estelle, an interior designer with designs of her own), each calculating the odds of surviving the sturm und drang of Jake’s and Vince’s relationship.

The believability of the brothers is the show’s make-or-break, and against expectation it works, largely because Law grounds Jake in that tensile paradox he’s been refining for nearly three decades: the glamour of control haunted by the fear of losing it. His Brooklyn accent sometimes wobbles; his performance doesn’t. Watch the way he exhales a lie, the way an apology catches in his throat—Jake registers as a man who learned reliability as a survival tactic and now has to wonder what it cost.

When I ask why he chose to play Jake, Law lets out a quick laugh. “If I’m honest, I got involved very much as a producer and didn’t really think about the role much. I don’t know, had it come my way, whether it was a role I would have jumped at… I may have jumped at Vince.” Why? “Well, because I just thought, initially, he could be a bit of a douche bag, and I really didn’t want him to be. But at the same time I was very hands-on [as a producer], saying, ‘Okay, there are little tweaks here I think are important.’ Like, ‘I think he’s got to be a good dad, I think he’s got to be someone trying his hardest to learn from his past mistakes.’ And you see him trying also to move out from under the shadow of his brother… And that all started to make him a little more interesting and real.”

Patterns: it’s a useful key to Law’s career. He arrives, seemingly, fully formed in 1997’s Gattaca, Andrew Niccol’s coolly luminous dystopia where genes decide your station and hope is a kind of contraband. As Jerome Eugene Morrow, a man genetically designed for greatness but confined to a wheelchair after a car accident, Law brought a volatile mix of patrician poise, brittle vanity, and aching vulnerability. It was one of his first major roles, yet already the signature elements of his screen presence were on display: the sly intelligence in his delivery, the ability to inhabit beauty while undercutting it with melancholy or menace. In a single, unforgettable scene, Jerome drags his broken body up a spiral staircase, the aristocrat undone by fate, and you glimpse the paradox that would define Law’s career—an actor capable of making glamour shimmer even as he reveals the fractures beneath.

The paradox had precedent. Earlier that same year, he was alarmingly mercurial as Lord Alfred Douglas in Wilde, opposite Stephen Fry—the kind of capricious beauty who unsettles the narrative merely by his arrival. That volatility became a signature, sharpened to a diamond point in Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley which landed him his first of two Oscar nominations. In the 2016 HBO series, The Young Pope, Law weaponized his looks into a meditation on power. He has an understandable aversion to being described by those looks, but what’s striking across the years is how he has turned that tabloid fixation into a tool, fashioning characters who reveal the moral failings and compromise that beauty can mask.

If Black Rabbit feels like another turn of that screw, it’s because Law is now shaping the ecosystem as well as the role. He talks about storytelling with the urgency of someone who’s watched too many good performances trapped in indifferent films. “Because it’s bloody hard, I think to tell a good story or to tell a story well in film form you are hoping for so many forces to align: the map you’re following in the script, what you get to shoot, the others involved, the edit, the appetite for that story… So that challenge is certainly what motivates me.” The theater, he points out, remains a necessary counterweight. “Theater is much more the actor’s medium… You get to review what you’ve done, figure out what works, but also relive it in the most beautiful way.”

“What actors need is editorial intellect—the discipline of knowing what to include and what to omit.”

It was theater that brought Law to New York in 1995, a pivotal year, when he lived in the East Village while performing on Broadway in Cocteau’s Indiscretions, a role that won him a Tony nomination, and which spared no-one’s blushes in an extended scene that required the young Adonis to be fully naked. Law’s impressions of 1990s New York have seeped into Black Rabbit, a contemporary series with the sensibility of the fin de siècle city he roamed in. Now he speaks of that era with the tenderness of someone describing an ex he remains close with. Nights had edges back then. You had to show up when you said you would; no one was filming your mistakes on their iPhone. Social media, he worries, has amplified the meanest instincts while embalming youthful foolishness into permanent record. He’s no scold—he’s raising children in this world and knows it isn’t that simple—but he is clear-eyed. “It seems to have encouraged what I see as a very lowbrow form of communication, which is sort of gossip, bitching, slandering and mean… for that to now be magnified and blasted through a microphone to vast numbers… God, no one should carry that poster for the rest of their life.”

If the ’90s is the decade he recalls as a golden time, it’s partly because he was young and partly because the culture had not yet dissolved into the micro-audiences of the algorithm. “It really did feel like a thing,” he says of Britpop London, of bands and actors cross-pollinating in a city that briefly believed it was the center of the world. But the idyll had limits. “I was a pretty boy called Jude in southeast London who wanted to be an actor in quite a working class area,” he says, recalling the skepticism that toughened him. “And that was sort of my rocket fuel. I was really enthusiastic. I didn’t know what to do with it till I came here.” New York gave him not reinvention but permission. “I remember coming here and just thinking, oh gosh, I can be me here.”

Law’s hits have been leavened by some bombs, but failing too, has its pedagogy. “I really believe that if you’re not failing once in a while, you’re not working hard enough,” he says. He cites Anna Christie at the Donmar—miscast on paper, he thought halfway through, until the performance proved otherwise—and Dom Hemingway, a film “no one ended up seeing,” that nonetheless unlocked a register he later used to play Henry VIII. The point isn’t the trophy; it’s the topography: mapping where the role ends and the caricature begins. With director Karim Aïnouz on Firebrand, in which he wriggled into Henry’s codpiece, he says the shared aim was “not wanting him to be a kind of chicken wing-chewing, ‘bring more hock,’ caricature. We wanted him to be a very plausible domestic monster…” It’s the word “plausible” that lingers—Law’s preference for specificity over bombast, for the chillingly ordinary detail that makes the power real.

That taste for specificity helps explain his reading life. He approaches roles like a scholar with a deadline—hungry, selective, alert to the line between comprehension and overreach. On an upcoming project about Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley Jr., he is animated by the range of reading he undertook for the project and which gave him a reverence for a time of heavy-weight intellectuals who were able to spar with their minds. “That’s at the heart, in a way, of the project—really remembering what it was when two people were able to argue at an elevated place.” He laughs at the notion that actors skip such indepth research; for him, reading is the ballast of performance. “The reason I do, quite simply, is because I have to be confident… I’d have that kind of ugh, sickness, that dread that I can get tripped up somewhere. At least I can say, well, I’ve got my opinion. I’ve seen this, I’ve gathered this. I know this much.”

“I really believe that if you’re not failing once in a while, you’re not working hard enough.”

It’s consistent with how he talks about playing living figures, including Vladimir Putin in an upcoming adaptation of The Wizard of the Kremlin, Giuliano da Empoli’s bestselling fictional political thriller. The novel, a sensation in France, imagines Putin as a modern-day Ivan the Terrible intent on restoring a sovereign Russia through the consolidation of absolute power. Law describes the challenge with characteristic precision: “Rather than playing the iceberg, you’re playing an ice cube,” he says of focusing on a specific period, in this case Putin’s early life. What made it possible, he explains, was trust in a director (Olivier Assayas) who is “subtle… suggestive… nuanced,” and a story calibrated to avoid the grandiosity that so often distorts understanding. Does he believe empathy is a requirement? “I think it’s always necessary, but I do think that part of the journey is finding the gap between you and the character, and the audience understanding that gap. I think you just have to find a truth, more than empathy.”

Truth, for Law, is rarely an abstraction; it’s the texture of a room, the smell of a century. (On Firebrand, he imagined Henry VIII as someone who “stank”—and wore a commissioned fragrance apparently blended from blood, fecal matter and sweat for verisimilitude). He’s especially alive to how audiences project their own moment onto a story. With Black Rabbit, he’s happy to hear that I read the show as a microcosm of larger moral corrosion taking place in Trump’s America. “I wonder also whether you could go a layer deeper and just say it’s about how hard it is to survive–the desperation, the mire that we’re all really in,” he says. “Because even the billionaires are sort of acting like cavemen–well, are definitely acting like cavemen, actually. It’s like, bloody hell! Or are we just more attuned to it now? I don’t know. Or is it just where our fascination is now, that we’re aware the moral boundaries are disintegrating and people are watching and thinking, Well, if that’s happening there, I can do this in my back garden.”

He’s wry about how grand narratives are often reverse-engineered after the fact, but he doesn’t dismiss them. The hunger to connect dots—to find patterns—is part of what makes the world hum.

As for the future, the one where AI makes movies and actors become synthesizable assets, Law declines panic in favor of pragmatism. “I don’t think we should panic… We know it’s a tool. We know also that if we understand it fully and use it as a tool, it can also benefit in the same way that CGI did… But we have to own it rather than feel like it’s running away from us.” The remark is classic Law: alert to threat, impatient with hysteria, keen to get back to the work. He’s not pretending all change is benign—he’s spent too long inside the apparatus to mistake a marketing deck for a destiny, and is aware that a movie like Ripley would struggle for funding today (“Those locations? No way!”), but he is betting on the one variable he can control: the standard he sets for himself.

Which brings us back to Black Rabbit, and to a city that taught him how to see stories in a room. I tell him I arrived early and watched the bar around the corner through the show’s lens, catching the invisible dramas braided into the after-work chatter. He brightens—this is the game he plays too. “If you can create that kind of a community as a basis for the show,” he says, “then you can layer in a sort of who done it structure.” The craft note becomes an ethic when he talks about why any of this matters. “I do think it’s a responsibility to a degree of questioning why you’re developing something, why you’re putting all this effort in… Is it relevant? What are we trying to say and why are we making it? Why are we making it now?”

But sometimes play is just play. He remembers making a film in Texas, and going to a bar in Austin to participate in a live reading of Samuel Beckett with Ethan Hawke. “It was fantastic,” he says. “It’s nice to pull the rug from under your own feet, I think. And you can do that in performance. I’ve been working on a piece with a wonderful playwright friend of mine—we’ve done a rehearsed reading, and we’re just thinking, Let’s just keep doing that. Let’s just keep putting it on wherever we both seem to find ourselves, spontaneously and give it no boundaries, give it no responsibility. There’s something wonderful in that.”

It’s part of the profound pleasure he finds in New Orleans, where he moved after wrapping Black Rabbit. “Obviously there’s some of the best musicians in the world there, playing some of the best music in my opinion. And a couple of my dear, dear friends are heavily involved in the jazz scene down there. One of them runs this incredible company and yet he still finds time to turn up at a friend’s random party where they just play on a porch. And he was talking about not letting that go. He was like, “Dude, you gotta keep doing that. That’s what keeps you alive, even though you’re tired.”

“If the young Jude Law was the spark, the Jude Law of today is the current—steady, forceful, impossible to ignore”

It’s tempting to read Law’s career as a sequence of immaculate surfaces cracked open to reveal their human cost—from Bosie and Ripley through Jerome Morrow and Lenny Belardo and Henry VIII to Jake Friedken. But that feels reductive in the face of the man in front of me: a worker, a reader, a father, a collaborator, someone who keeps testing the boundaries of performance not by inflating himself to fill the frame but by burrowing down into the particulars—how a person smells, what a room does to a voice, where the line sits between empathy and truth. He seldom indulges nostalgia, but when I ask if he misses Hamlet, he tells me about Mark Rylance’s advice—“Do it again”—and laughs off the suggestion. There’s too much else to try. “I’m too old now anyway,” he adds wryly.

If the young Jude Law was the spark, the Jude Law of today is the current—steady, forceful, impossible to ignore. He has learned to accept failure as part of the job, to guard rehearsal as a sanctuary, and to value aging as a ripening of perspective and self-knowledge. Our exchange drifts in the way Law clearly enjoys—hopping from Abraham Lincoln’s stump speeches to the decline of public argument, then onto Ralph Lauren’s instinct for designing into the future, an insight gleaned from a documentary Law watched on his flight from Paris.

Law doesn’t just absorb these digressions; he works with them, folding each into his own thinking about performance. What actors need, he suggests, is “editorial intellect,” the discipline of knowing what to include and what to omit. That, in the end, is what the best performances do: edit reality until it becomes legible. As for whether he shares Lauren’s antenna for anticipating the future, he shakes his head. “I get a sort of whiff of that,” he says, “but I also have a sense that if something is interesting enough to me or to those around me… then I just hope that other people will find it interesting too.”

Hope can sound like a soft word, but in Law’s usage it’s braced by craft. Watch Jake in Black Rabbit pause before a lie, watching himself choose; watch Jerome in Gattaca haul his broken body up a staircase, not out of nobility but pride; watch Lenny Belardo pray like a man negotiating with his own reflection. Patterns recur because the human drama does. Law’s gift is to make those patterns feel freshly perilous each time, as if he were discovering them in the moment—on a stage in London, in a bar on Avenue A, on a porch in New Orleans. To borrow his own dichotomy, he is still waving, not drowning. And if that wave looks exuberant, it’s because he has earned the right to move that way—against the current, toward the next story.

Stylist for Jude Law Brodie Reardon. Grooming Laila Hayani at Forward Artists. Photo Assistants Donna Viering, Aijani Payne. Stylist Assistant Jody Bain. Tailor Susan Balcunas. Production Director Lisa Olsson Hjerpe. Production Kitten. Executive Producer Mahaut Lefort. Production Manager Leon Estrada. Retouching by MAY. Shot at The Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation. © 2025 The Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.