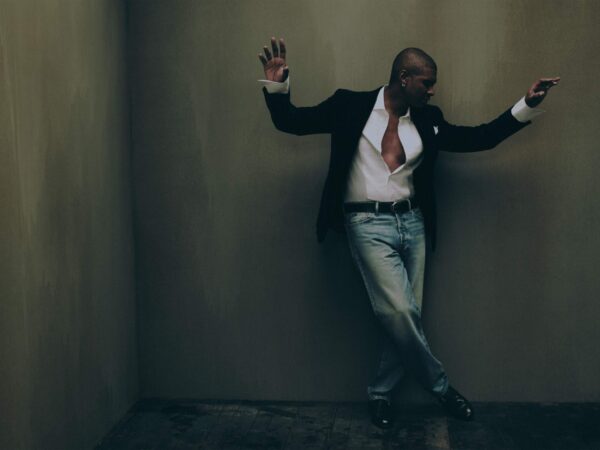

For the inaugural issue of Notes on Beauty, Academy Award-winner Julianne Moore muses on the dual nature of public and private personas with writer Whitney Mallett

Women love Julianne Moore. She has a quality, and an oeuvre, that endears her to devotees of both artifice and naturalism. I think it’s her eyes, the measured restraint with which they can play an intense, consuming yearning. We see it twice in a matter of minutes in Christian Marclay’s video-art magnum opus The Clock, a 24-hour montage of timepieces in film and television. At 7:14 pm, Moore’s character in Chloe (2009) receives a call from her husband who’s missed his flight and, subsequently, the party she’s planned. At 7:18 pm, Moore reappears, this time in a scene from Far from Heaven (2002), waiting on a call from yet another on-screen husband, this time in a 1950s mansion. Her eyes narrow, her eyes drop, a soft furrow of the brow, a twitch at the corner of the mouth—these precise gestures offer a glimpse into interior worlds and hidden currents of an American underbelly. “The Sphinx Next Door” was appropriately the title of Moore’s New Yorker profile a decade ago. In the years since, she has only further honed this preternatural ability to evoke great mystery, convincingly ill at ease within suburban confines. Her resumé is filled with films by Paul Thomas Anderson, Alfonso Cuarón, David Cronenberg, and Rebecca Miller. Most recently, she starred opposite Tilda Swinton in Pedro Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door (2024) and Sydney Sweeney in Michael Pearce’s upcoming Echo Valley (2025). Yet no collaboration has been more career-defining than with director Todd Haynes, a partnership that started with their illness-as-metaphor masterpiece, Safe (1995), about a housewife suffering from toxic exposure. Their latest was May December (2023), which has a defining scene centering around the transformative power of makeup—albeit the tone more ominous than uplifting. Moore plays a woman whose past is marked by the scandal of seducing a 13-year-old boy she later married, while Natalie Portman plays an actress spending time with the family to research a role. Moore’s character shows Portman’s how she applies a buildable cream blush with a sponge, the scene shot from the point of view of a mirror.

“We’re often creating what we think is beautiful. When we can divest ourselves of this idea that beauty is somehow visited upon us, it’s freeing.”

Whitney Mallet: I really feel like I already know you.

Julianne Moore: That’s funny. I just said that to somebody whose work I watch a lot. It’s a weird feeling, right? But it’s also kind of fun.

Whitney: Well, the brief is beauty. Since we’re doing this over Zoom, I was thinking about lighting. So much of beauty is lighting. I have the worst lighting right now. I’m in a windowless room.

Julianne: You might not have any natural light, but with those white walls, you’ve got a lot of bounce. Also, you’re young, so that’s all working in your favor.

Whitney: Right, I’m getting some diffusion here.

Julianne: This goes right into what is beauty. When you say a lot of beauty is lighting, you realize that beauty is a construct. We’re often creating what we think is beautiful. When we can divest ourselves of this idea that beauty is somehow visited upon us, it’s freeing.

Whitney: More and more, I feel freed from this idea of wanting to be ‘beautiful,’ but I want to feel like I’ve self-actualized my image—to see a photo of myself and not be shocked.

Julianne: So we’ve established beauty is a construct. It’s political or cultural, depending on where you are. And now we’re moving away from beauty being empirically something other, and bringing it closer to your feeling about yourself. I think that’s a good thing. Not to sound corny, but the more you get to know someone, you do fall in love with their essence, with their way of being. Sometimes you find a photograph or a painting of someone who was considered a great beauty of their time, and by our standards, they don’t look that beautiful. You realize it wasn’t necessarily a physicality. Sometimes it is just how someone moves through the world, how they project themselves.

Whitney: When you’re young, you become aware—sometimes quite suddenly—of how you inhabit these constructs. I remember becoming aware I possessed something outside myself, and it was something I felt alienated from, or sometimes wanted to rebel against. Did you ever have an epiphany like that growing up? Realizing how other people perceived you?

Julianne: I was always aware of how your physicality and your behavior are mutable. It was something that I realized because we moved around so much. A lot of the things other people thought were givens in terms of what personhood is, I knew weren’t. That led me to acting and to my connection to narrative. I thought it was interesting how differently you could be perceived from place to place. I’d be at a school where no one thought I was interesting or attractive. And then I’d be at another school and suddenly I was interesting. I knew I didn’t change, but suddenly people perceived me differently. That was a really important thing to learn. Oddly, for someone who’s an actor, I crave neutrality. I think it’s because of that moving around. I want to have a neutral core that I bring from place to place.

“That wonderful photo of me with the flowers coming out of my mouth. When I saw it, I was like, wow. It’s just so them. They have such a wonderful point of view. It’s arresting.”

Whitney: How about having red hair?

Julianne: The worst! That’s the worst for somebody who craves neutrality. I was like, ‘Ah! This is such a huge defining characteristic.’ And yet, when I got older and had the opportunity to change it, I didn’t, because it’s just what my baseline is. But I did find it challenging. It felt too defining.

Whitney: I want to know about your mother. I read she was a psychologist. So many of my issues, or at least my ways of relating to beauty and self-perception, are really defined by my mother. As a young girl, you watch your mother put on makeup or do her hair.

Julianne Moore: My mother was very beautiful and very young. She was only 20 years older than me. That was interesting because I felt like her beauty and her way of being in the world were easy. It didn’t feel effortful. She was always beautiful. She was always the youngest mom. It felt good to watch her get dressed. She was lovely, but I also didn’t think a lot about it. I thought more about the fact that everything changed all the time. Beauty didn’t feel like a solid thing to me.

Whitney: It’s always a dance. Our projection of what we want people to see is also based on how people are seeing us. I’m always thinking about this dynamic, and about charisma too. It’s hard to know if you influence people to think you’re charismatic, or if you think you’re charismatic because of how people treat you.

Julianne: A lot of charisma is the attention that you give to others. People will talk about somebody being naturally charismatic, and you realize that that person has spent a lot of time connecting to other people. It’s often the way they are making someone else feel that makes them charismatic, which I think is kind of wonderful. It really is kind of circular.

Whitney: I read a definition of charisma the other day that was about how we enjoy being around people who demand nothing of us. Like if you don’t show up to their birthday party, you don’t feel this weight.

Julianne: [Laughs] Yeah!

“People will ask if you want to keep your clothes from a movie. They’ll be like, ‘Do you want those pants?’ I’m like, ‘Yes, I want those pants.’ And then I get home and I’m like, ‘I can’t wear these pants. These aren’t my pants.”

Whitney: Do you ever use beauty as armor? Is there a certain hair or makeup you gravitate towards when you feel vulnerable?

Julianne: Because of what I do, I feel like hair, makeup, and fashion are less like armor. If I’m out in the world with all this stuff, really made up, I don’t feel particularly armored. I feel like I’m asking everybody to look.

Whitney: It’s more like a target.

Julianne: I feel better in this place of neutrality. That being said, I love what I do. I love doing photo shoots with great photographers. I love wearing fashion. I love the access I have to all these creative people in the beauty industry. The makeup artists, they’re painters. They’re creating something on your face. The same thing with hair stylists. We’re back to that idea of beauty being something that we construct, and we create it together. Like the way we did for this photoshoot with Inez and Vinoodh. The way they frame people. How they see them. That wonderful photo of me with the flowers coming out of my mouth. When I saw it, I was like, wow. It’s just so them. They have such a wonderful point of view. It’s arresting.

Whitney: These roles you take on—the transformations that happen in the hair and makeup chair. I’m obsessed with imagining you getting ready on the daytime soap, As the World Turns. That era.

Julianne: What, the ’80s? [Laughs.] On television, in film, on stage, in real life, it doesn’t matter where, everything that somebody wears, and how they do their hair and the way they’re made up, is a signifier. It’s a code to the world about who this person is and how they would like to be perceived. On that soap opera, I played one character who was supposed to be very good and another character who was supposed to be kind of evil. For the nice character, I wore a lot of pastels and my hair was all kind of lovely. And then my other character had a dark wig, she wore glasses, and her clothes were serious. She had an edge. I think that’s one of the reasons I crave neutrality in my life. Because I spend so much time thinking about who a character is, how they project themselves into the world, in order to tell a story.

Whitney: So many of these iconic roles you’ve played, they’re all coded, like you say. Down to something like the precise metallic eyeshadow on a character like Amber Waves from Boogie Nights (1997). Is there ever any part of that transformation that stays with you, or is it always returning to neutral? Are you ever like, ‘Oh, this way of doing my eyebrows, maybe I’ll keep that’?

Julianne: I dump it. You start to really assume it while you’re doing it, and you enjoy it. Sometimes it definitely seeps into your own life, because you can’t help it. Then the minute it’s done, it’s gone. People will ask if you want to keep your clothes from a movie. They’ll be like, ‘Do you want those pants?’ I’m like, ‘Yes, I want those pants.’ And then I get home and I’m like, ‘I can’t wear these pants. These aren’t my pants. These pants belong to her.’ We’ve thought very hard about how long her hair would be. What color would her hair be? How much makeup does she wear or not wear? What’s her jewelry like? Is she tall? I’ll deliberately wear really, really high shoes for jobs where I feel like the character should be taller.

Whitney: Are these collaborative conversations with the directors and filmmakers you work with?

Julianne: Some directors are very interested in these conversations. Some are not.

Whitney: I imagine Todd Haynes has lots of opinions. He does, but he’s also incredibly collaborative. He’s interesting. He wrote Far From Heaven for me, and when I got the script, the character was described as having red hair. He was like, ‘I wrote it for you, and you have your hair.’ I was like, ‘Todd, I just don’t think she’d be a redhead. She’s the quintessential American woman. She should be the 1950s heroine. The American blonde. The blonde woman driving the blue car. That iconic figure.’ And he was like, ‘Okay.’ So my wigs have a little bit of strawberry in them, but they’re mostly blonde, because I said for her to have red hair like me makes her too much of an outsider. It makes her too edgy. So that makes him a great partner. He listens.

Whitney: It’s so clear watching films you guys have done together that you have a beautiful relationship.

Julianne: I love him!

Whitney: Carol White in Safe—how did you guys construct her beauty?

Julianne: It was a very, very low-budget movie. A lot of the clothes weretaken from Universal—clothes they use on television shows you can borrow. There were also a lot of clothes that belonged to Todd’s mom. Again, it was a certain kind of American femininity we were looking for and for a particular time period. The perm was part of it. This idea of wanting something that ultimately is toxic—actually physically toxic. It was a very prescient way to look at beauty.

Whitney: My mom used to go across the border to get this keratin treatment that used formaldehyde, like a reverse perm, because it was banned in Canada, where we lived.

Julianne: I would get that too! It’s really rough. I don’t know that I would do it now.

“Oddly, every time you dissolve this idea of “I” or selfhood, and you seek a connection with another person, suddenly you do feel more human, and more connected.”

Whitney: Part of the concept of this new magazine is to ask: How does beauty relate to who you truly are?

Julianne: Who you are according to whom? You only know who you are sometimes in opposition to something else. And if the other is changing all the time, then you’re going to change too.

Whitney: I mean, implicit in that question is the idea that there is a true you.

Julianne: Yeah, a self! Which is something we all struggle with. Is there a self? We don’t know!

Whitney: I don’t feel like there is one. I’m a textbook codependent though. I might not know myself, but I feel like I know who my friends are. Or at least, I know their taste—who I understand them to be through their lifestyle consumption. All these things they’ve curated to tell about themselves.

Julianne: But again, they’re signifiers, right? If you’re signifying something, you’re saying either ‘I know who I am, therefore I’m putting this into the world,’ or you’re saying, ‘I would like to tell you that I am this’—it doesn’t necessarily mean that you are this, just that you are saying, ‘I am this.’ That’s why I said I crave neutrality, because I have no idea.

Whitney: It’s a trip! Sometimes I feel I don’t know who I am. But I do feel like as I release expectations of me, I can at least become more self-possessed.

Julianne: I think anything that makes you feel more connected to another human being, and less isolated, you will feel more yourself. Oddly, every time you dissolve this idea of “I” or selfhood, and you seek a connection with another person, suddenly you do feel more human, and more connected. It takes that dissolution.

Whitney: Which almost feels Buddhist.

Julianne: Absolutely.

Whitney: Is there a time when you feel the most present?

Julianne: I think in ordinary life. The more I simplify my behaviors. My connection to others. The stuff I do around the house. Being with my family. Those are the things that make me feel most present.

Whitney: Also, what’s your nail color?

Julianne: It’s a gel. I was just in LA for the Spirit Awards and I wanted dark nails. It’s the closest they had to Chanel Rouge Noir.

Whitney: It’s neutral!

Julianne: A classic!