From the Picturephone to the present day, the Mumbai-based collaborative studio explores the politics and poetics of the moving image

The Picturephone had a console like a bullet camera, a three-dimensional Eye of Providence. Presented by AT&T at the 1964 World’s Fair, then decades after its debut and stalled development, the video calling system offered visitors the chance to converse with the distant, with those otherwise inaccessible. At the Fair, this mostly entailed the people in the booth next door, but the system promised intimacy and proximity: one could dial a number and find the face of a family member upon the oblong, futuristic screen. It implied a kind of humanism via network, a global village, an interface of mutual recognition. “It will let you see who you are talking to,” one ad declared, “and let them see you.”

The fair’s theme that year was “Peace Through Understanding.” Video was, presumably, the medium upon which this transformation would occur—all those midcentury rhetorical imprints of democracy and freedom. The wide-eyed exuberance is stark. And yet the optimism, the affectionate desire to see and be seen by others, is a sentiment often retained.

It is, as a kind of ethic, often taken up by the Mumbai video collective CAMP, a selection of whose work is currently on display at MoMA in Video After Video: The Critical Media of CAMP. In the Khirkeeyaan series from 2006, the group’s artists used existing cable TV wiring and CCTV to set up video portals in Khirkee Extension, allowing residents of Delhi’s urban village to speak from different locations. The conversations are full of hope. In one setup, several women discuss their ethnic backgrounds and experiences of harassment; elsewhere, textile workers stare with inquisition at the factories which look much like their own. Video is the transparent ground on which viewers can hear the declarations and stories exchanged between these residents. One man clears his throat and says into the microphone, “I pray that this love and togetherness will grow between us.”

The enthusiasm for accessible video was abundant in the 2000s, granted popular and commercial scope by Skype’s debut in 2003. But this ideal was accompanied by a skepticism toward the overexposure it produced. Well into the 2010s, artists and media theorists focused their attention on the technologies of watching which were sending the image into flux. David Spriggs redesigned Bentham’s panopticon in an array of glass sheets, an “architecture of imagery”; Hito Steyerl included as the first lesson in her cult classic “How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic .Mov File” (2013) instructions on “how to make something invisible for a camera.” A paradigm of visuality—of making and dealing with images—was the means by which much critical work addressed a culture of proliferate surveillance.

CAMP, too, produced several installations in the late 2000s indicative of this tonal shift, attending to the dynamics of image-based representation that surveillance constructs. Often, these works sought to address the phenomenon of being watched as an imposition to be addressed, regulated. In Coldclinic, from 2008, a few dozen people were invited into CCTV control rooms in Manchester, offering their scrutiny and experience of looking at footage otherwise deemed privileged; in Capital Circus, subjects were filmed on CCTV after signing release forms, which stipulated that “we can all claim the right to our identity in public space.”

The works on view at MoMA trace an adjacent trajectory, not always through surveillance footage but concerned nonetheless with video’s twin principles of documentation and oversight. In addition to Khirkeeyaan, the exhibit includes From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf (2013), a work of cell phone and VHS-C footage recorded by sailors traversing the Indian Ocean, and Bombay Tilts Down, from 2022, a multi-screen installation of footage from a remote-controlled surveillance camera atop a building in Mumbai. “Take the scene well,” a man proclaims to the camera in From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf. “Then they will know, and see, our situation.” Watching the daily activities of the sailors, however, a sense of alienation set in—fantasies now thrown into sharp relief.

Since these words were recorded, the dream of connection—of “Peace Through Understanding”—has become burdened with the connotations of naivete. The internet has given way to platforms, omniscient vertical vision to distributed sensor networks and the internet of things; devices have created an abundance of metadata to be stored and manipulated for profit and intelligence. The shift may not be binary, but recording practices and digital communications now seem more alienating than not—and the politics of visibility, of seeing and being seen, is not the politics of photography and video.

Video after Video is certainly aware of the extent to which its earlier hopes have been undermined. In the more recent work Bombay Tilts Down, from 2022, CCTV footage is dispersed across seven screens, akin to a folding room divider; it is impossible to view all the screens at once. Wide shots of construction settings pan downward, toward the street scene activities of dockworkers, children, drivers. Some of the Bombay residents on screen notice the camera—they stare and chuckle, point and tell their friends. The remote-controlled lens quickly pans away, as if frightened by their recognition. Unlike the earlier works on display, Bombay Tilts Down is skeptical, hard-boiled, more hostile to spectatorship.

The sharper tone is tempting, a challenge to the omniscience of video. It seems to recognize that earlier technologies like cell phones and live video have in fact given way to a sense of ubiquitous voyeurism. But there is still something limiting—perhaps even more naive than blind optimism––about a trajectory that begins and ends with the camera. Though less quixotic, Bombay Tilts Down focuses on the ubiquity of CCTV, another moving image which documents people moving through the world. It limits resistance to that which defies and addresses the lens. It bestows authority upon a medium, albeit if only to undo it, whose primacy has waned.

It is an ethos laden with an older sentiment: the post-Snowden suspicion toward webcams, as well as the enthusiasm about the utility of mobile phones during the Arab Spring protests across North Africa. The potency of these events was and is contingent on ideas of collection, storage, and documentation—as much about watching as being watched.

Digital methods of communication and surveillance don’t always require that body, that “real world,” that visibility: the person on the street corner whose face is recognized, the young man playing chess on a boat crossing the Indian Ocean. Representation is more abstract—the LLMs and VLMs whose dimensions correspond to attributes of information rather than physical space, or the digital biometric renderings whose model of the body is far from an object appearing on camera. Surveillance has given way to data collection, modelling rather than record-keeping; the vision plot, a drama of seeing and being seen, is a relic here, an antiquated antagonist.

The exhibition presents a premise: “How do we make sense, or poetry, out of the system of images we face today?” But this system of images now seems eclipsed by a broader system of representation, something more entangled in the techniques of information and data than photography in its strictest sense. The moving image, then, seems untenable: an artificial menace, a caricature of itself, suspended between nostalgia and futility.

It is easy to wonder if the opaque and intangible nature of information requires artists to respond in kind, and to conclude that video is no longer up to the task. In 2014, the writer Trevor Paglen published an essay rethinking Harun Farocki’s concept of operational images. In his canonical Eye/Machine I, from 2000, Farocki examined the process of image production occurring within and for machines as part of a particular function. The machines did not “see” these images like humans did. By the time of Paglen’s essay, however, this was already outdated—machine vision no longer generated images interpretable to “meat-eyes” at all. Machines were always reading images as information, but now there was no photography proper involved at all, nothing human in the loop. “I don’t know how we will learn to see this world of invisible images that pull reality’s levers,” he wrote. The tether between images and representation was fraying amidst ever-renewed declarations of photography’s end—an obsolescence settling into old forms.

Works which deal in abstraction, artificial intelligence, and the apparitional vocabulary of information––in the immaterial—have the appeal of being more timely, more seductive in their rhetoric. The activity of neural nets or the generation of data is opaque and only intimated; in the works of artists like Addie Wagenknecht and Phillip Schmitt, it is an echo of something which cannot be shown on the terms of the image.

The exhibition of CAMP’s work, on the other hand, is an insistence on the document, on the visual appearance of the world on camera. It is not an entirely false reminder. Three years before the release of Bombay Tilts Down, Delhi police were using CCTV and facial recognition programs to identify protestors engaged in demonstrations against the country’s 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act; in the United States, too, there has been recent concern about the use of facial recognition at protests for Black Lives Matter and for Palestine. Declarations of a post-visual or post-photographic condition certainly eclipse the persistence of these technologies, favoring the rhetoric and tensions of posthumanism. CAMP refuses to abandon the physical world of life in public—the activity we can still see, it seems, rather than the mechanisms to which we often lack access. These are different strategies of representation, of addressing what information looks like anymore, how it is witnessed and collected. At times they seem to some extent incompatible, irreconcilable.

In addition to AT&T’s Picturephone, the ‘64 World’s Fair included mock-ups of the future designed by General Motors: a model of the American Southwest, for instance, in which remote-controlled machines harvest crops in soil irrigated by desalted sea water. Nearby, a weather station, far below the surface of Antarctic ice, in which technicians prepare global forecasts. Compared to the whimsy and delight of the Picturephone, these constructions are a truer, more precise origin of the direction telecommunications and data science have taken in the past half century: oversight and extraction, careening toward destruction in the name of optimization. If live video was launched under the rhetoric of connection, the models nearby indicate a different kind of future—one in which the site of connection is precisely where the resource of information is generated and instrumentalized, without the image at all.

In a shot included in From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf, a man lies in repose, his head resting on a torn potato sack. The camera pans up from his bare feet, pausing briefly at his half-smoked cigarette. As the shot moves to his face, he takes a drag, peering at the cell phone which records him. Somewhere in the Gulf of Kutch, the shot asks something of viewers: here, look. These are the same terms on which the surveilled body appears to the camera, like the slapstick-startled Charlie Chaplin of Modern Times, sneaking a bathroom cigarette before his employer appears over one-way video surveillance: here, look.

Within the exhibition, the site of connection––its potential as well as its exposures––is limited to that in which the camera and the body meet. But if there is a remaining optimism, it is perhaps more tenable in the abstraction of that instance, in more flexible notions of being visible. It just may articulate conflict without anachronism, renewing the ambitions once broadcast from a low-res sea.

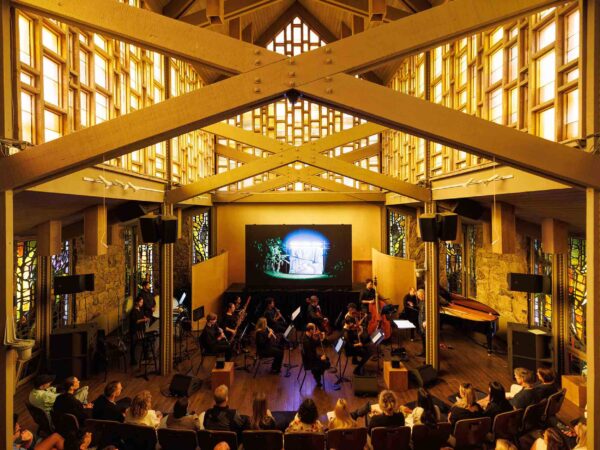

Video After Video: The Critical Media of CAMP is on view at MoMA until July 20th.