On view in Chelsea, the Filipino-born, London-based artist’s latest solo show gives utilitarian objects a new meaning

At the heart of Nicole Coson’s terrific New York debut at Silverlens Gallery is the single recurring image of a plastic shipping crate—ubiquitous, unobtrusive, perpetually in transit, everywhere and nowhere. Whether intentionally or not, it evokes the instability and uncertainty facing all immigrants, or anyone who has ever found themselves between worlds, marking time with nothing that wouldn’t fit into a crate. The echoing title, In Passing, also suggests some kind of tie to the harrowing realities of forced migration and displacement in Ukraine, Gaza and beyond. Make of that what you will. But no allusion to world events and the like could obscure the fact that here were impressive and quite singular works.

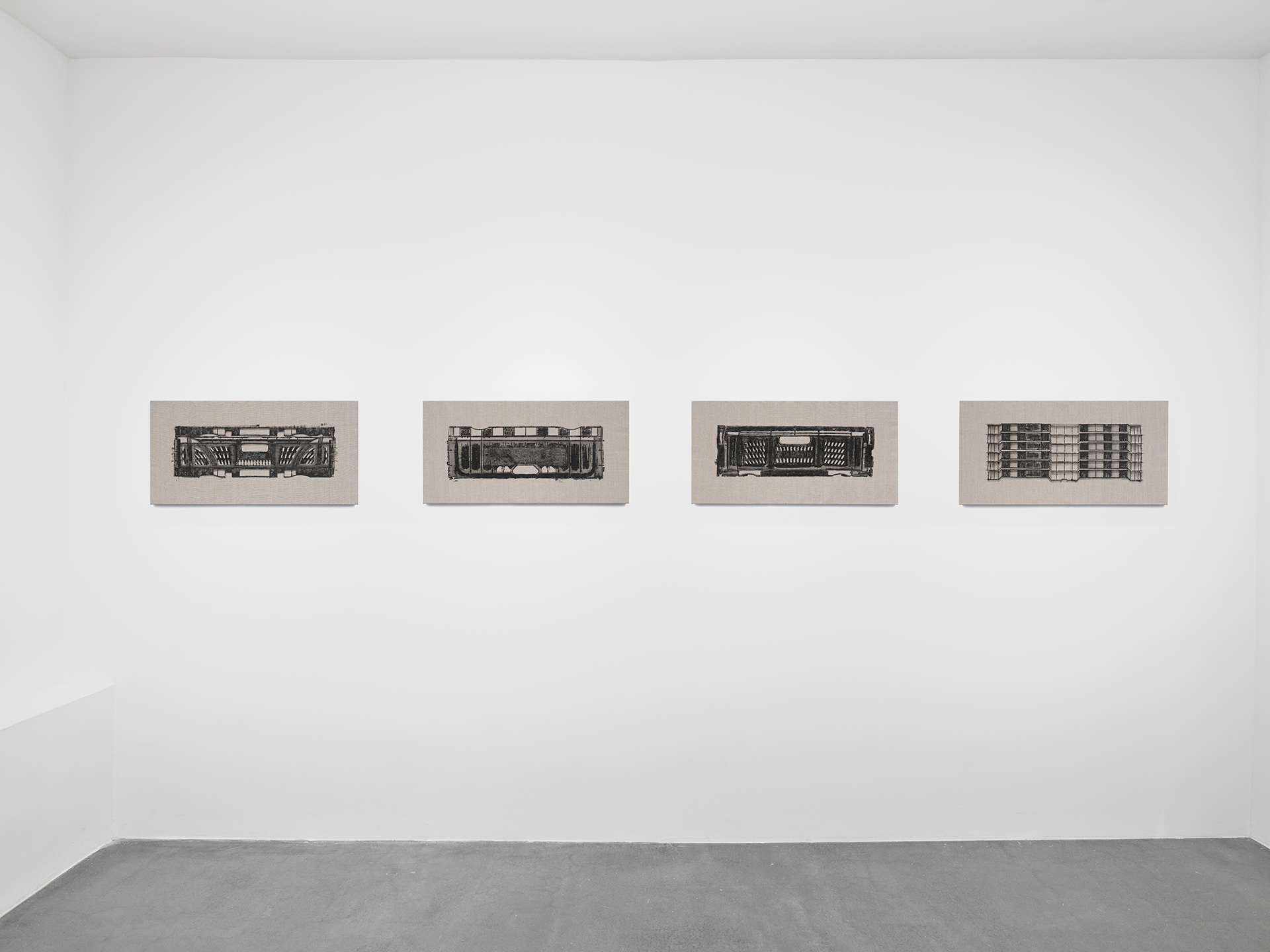

The show, on view until April 20, features eight oil paintings, none of them titled. The three strongest and most monumental canvases commit to a simple motif: tall towers of black crates, just about life-size, precariously stacked and then repeated horizontally over large stretches of linen, until they achieve something of a ruthless, factory-like order. The result feels architectural. From a distance, the crates resemble hard-edge highrises, but stare long enough, and they slowly assume the mystery of a tightly packed Modernist grid.

If there indeed exists a broader social and political thesis within In Passing, its articulation mostly follows the general contours of post-Minimalism. And not just aesthetically. The approach calls to mind artists like Hanne Darboven, Kazuko Miyamoto, and Dorothea Rockburne, whose ideas come from self-imposed restrictions. Coson has nothing but the crates. By multiplying them, she renders their function progressively unintelligible, the way repetition causes a word or phrase to temporarily lose meaning for the listener. The crates dissolve as quickly as they form a recognizable image. What remains thereafter is a picture of pure objectness, stripped of any human frisson. Talk about the experience of immigrants.

Coson was born in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, but she has lived mainly in London since graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2020. She has, from the start, an extraordinary sensitivity to the texture, weight, and feeling of materials. As much a physical feat as an artistic one, several of the paintings in this show are really monotypes made by applying black paint to the crates, which she then presses onto linen. Others adapt Max Ernst’s transfer technique, which involves her laying canvases on top of the crates and then using the impressions to make rubbings. The incurring smudges, stutters and overlapping fields of paint undulate like sea swells. Just gorgeous.

That little bit of perceptual disorder is what’s missing from the installation that hangs from the ceiling of the room. Some place, within here (2024) features five ropes of oyster shells, cast in aluminum and threaded between interlocking metal loops. According to gallery literature, it mimics the makeshift structures used to farm oysters in Aklan, a Visayan province in the Philippines. Conceptually it is a beautiful piece, cultural and confrontational. So much so that it demands a separate space. Here it is not unlike a site-specific work that has been removed from its original location. Perhaps that’s the point, but it has not managed to become something that seems inevitable, the way David was always there in the marble. More importantly, the process has somehow flattened the psychological complexities that make the paintings so distinctive and absorbing. But the right idea is there.