The New York–based artist and writer merges sound, sculpture, and sport in their debut solo show

“I might’ve told you I was guided / drew a set of drawings last spring filled a whole pad / felt my hand guided by a force, shapes and visions, haptic pitches, / my hand skating on fog,” reads the first stanza of one of Kaur Alia Ahmed’s poems mounted on the wall in Chinatown’s Entrance gallery as part of the New York-based artist’s debut solo exhibition, sky, harp. The installation—a combination of digital prints, custom lighting, glass sculptures on metal platforms, video, and sound—coheres as if under some elemental force: not one without intent (as if guided from without), but with an athlete’s control and hard-earned effortlessness. The fog has settled and all is dew and ice.

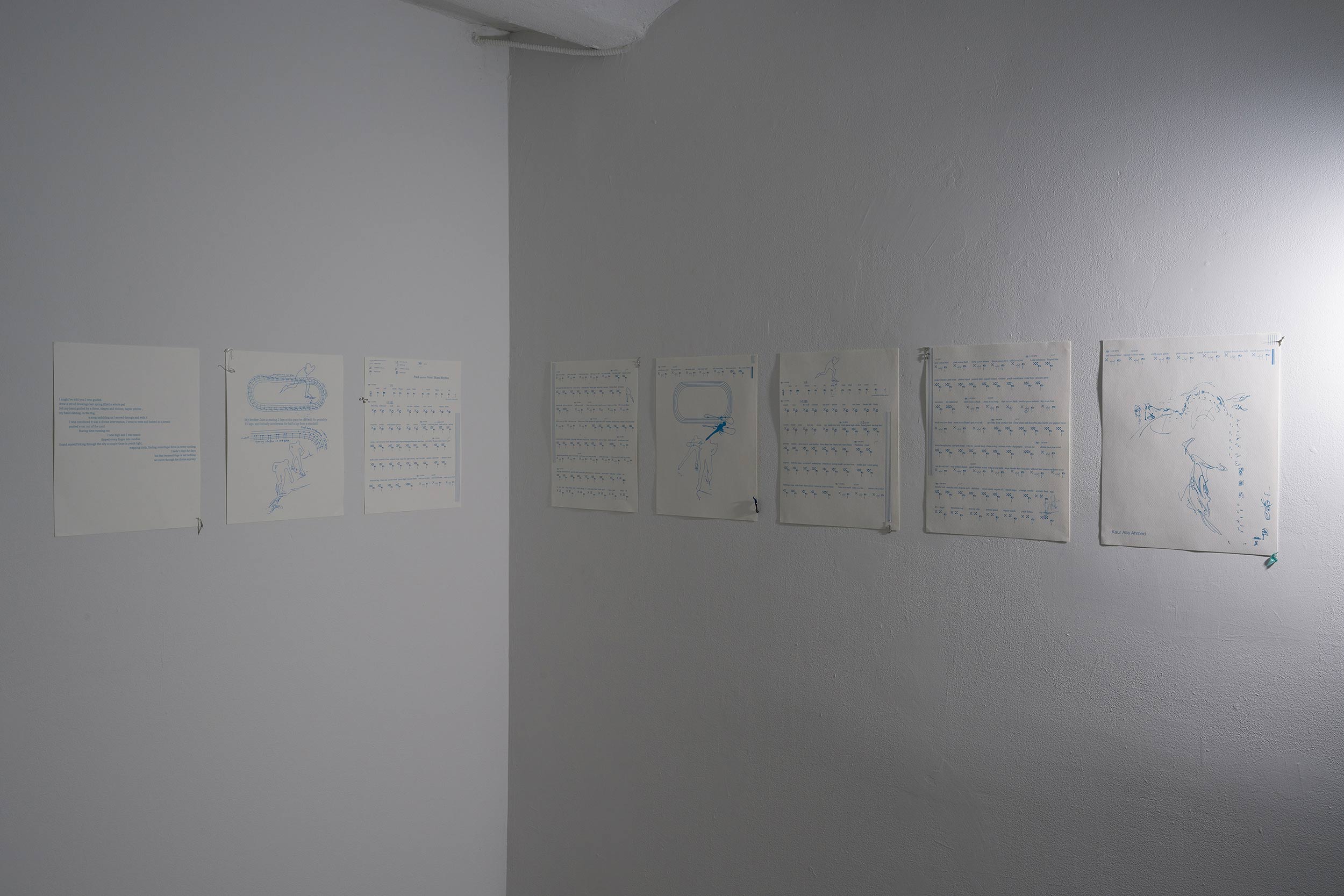

“Spins split like |chill chain lust stand still oh concrete else…” Ahmed’s poetry renders language more real for having made it strange. Reforged syntactic chains converse with some lush and giddy truth behind and beyond idiomatic convention. In sky, harp, their poems, mounted in the basement gallery like photos or paintings, crystalize the installation’s facture: the slant rhyming of reading and seeing, speaking and making, hearing and being.

The gerund—the action turned noun—might be the structuring grammar of Ahmed’s anti-grammatical space-text. Or that other -ing, the progressive tense: grammar as perpetual motion. Biomorphic glass works, themselves the suspension of fire and sand and breath, gather on the floor. Light flits through these amorphous oblongs: a projection of their brother Zain speed skating in Lake Placid, New York. Ahmed invited Zain—who in addition to being a committed ice skater is a physicist and imam—to collaborate with them on a project in early 2023. What began dialogically evolved into a melding of forms, with the siblings using the patterns of Zain’s skating to construct a score from which the various languages, objects, and images of sky, harp grew.

While Zain’s skating is on display in a projection, there are no sounds of wind or scrapes of ice. Before descending into the basement space, one hears Indian classical drums responding—as we later realize—to his movements, his circulation. Speech, writing, and the body become scores, riven with symbols strange and familiar, pieces of life, particles about to collide.

Drew Zeiba: In this exhibition you have these poems-slash-musical scores mounted on two walls; they’re also sort of drawings, or maybe even wall texts. Where did they come in the process of making sky, harp? How did you begin to generate this installation?

Kaur Alia Ahmed: It began with my brother and I writing a dialogue together, that not really working, but me being left with material from our conversations. I also wanted to film him skating to see it and understand the rhythm. For the scores, my brother transcribed his skating rhythm using this online score program that had all these notes in it—drum beats that were symbolized with Xs, quarter notes, etc. I then laid them out in the document and stylized my own symbols, and started to fill in poetry. It’s exciting because I don’t often follow form when I work in this mode. When they were quarter notes that were spaced out, I tried to use really short words for a staccato effect. And then where the score was indicating cymbals, I was using words like ‘flex’ or ‘exquisite’ or ‘exhale’ that literally have an X quality. Other notes are words or syllables that lift off more.

Drew: In your work the materiality of language asserts itself, in part through this sonic aspect, as well as through how you work with it visually on and off the page. I’m wondering how you think about language—and text—in relation to materialization and dematerialization, and to all these different media and forms.

Kaur: When I’m writing I’m thinking of the language almost like onomatopoeia, or an expanded version of it. I’m asking: What is that word? What does it do? What does it feel like as a thing in the world? The titles for many of the works include Gliss. The name comes from the term ‘glissando’: a slide or roll between notes, which happens a lot in singing. I was like, That’s what my brother is aiming for. But the text I wrote is not gliding. It’s funny, because it’s set up as lyrics, but then it’s hard to read aloud. And that’s intentional. It’s not a flowing melody.

“Sound feels parasitical in the way it puts something else within your body.”

Drew: One weird thing with onomatopoeia is that it’s very much the exception in language. Most words are arbitrary—‘apple’ as a series of sounds has nothing to do with resembling an apple as an object. But onomatopoeias do have a mimetic relationship to the world. Does this strange relationship between representation and language play out in how the glass and metal objects relate to the scores or poems?

Kaur: They both have the same kind of speed and instinct while also needing to be really precise, which is something I feel is in my drawing, too.

Drew: Your drawing, some of which is on the scores, often appears to me to have an emphasis on continuity or flow.

Kaur: There are a lot of continuous lines. Continuous lines plus dots. It’s like cursive. Making the glass felt like drawing because it had to be so fast. It’s a material that shows [your] movement, as in drawing. I was new to glassmaking, so I didn’t really know how it would work. But I worked with the glassblower and we sent sketches, drawings, videos, and images back and forth as references, and then practiced with smaller forms so he could show me what shapes were possible. On the actual day that we did it, I drew on the floor in chalk, which is a glassblowing thing. We had all these forms and shapes in mind, and then he handed me sculpting tools and we went for it. I was imagining the biggest forms in this series as vessels that were somewhere between ice and plants and an organism.

Drew: Your writing nears and veers away from familiar syntax. You can sense something is holding it together, but it doesn’t seek to invent a “new” grammar. The effect sort of escapes description.

Kaur: I like to mess with grammar. [Laughs.] I like it to feel somewhat familiar to speech. I also play with conversational affects, affects from a good article, a scientific description, or an ingredients list. Speech as in a text message rather than talking out loud. And people are always like, ‘What’s up with your punctuation?’ Sometimes I’ll capitalize words that are not proper nouns, almost as if I’m putting quotation marks around them.

Drew: But the musical scoring is insistently systematic at some level.

Kaur: I like to break systems. I don’t like systems. But then I guess I kind of do like making up my own systems. Arranging this poetry within something that looks like a system might make it so that a reader finds some logic or code in it. I want to do a reading with my brother because he’s very logical. He’s going to be like, ‘This doesn’t make sense.’ He disciplines himself with sport and God. I guess this text is also me figuring out my own relationship to control and discipline through writing.

Drew: Let’s talk a bit about your brother and his most literal presence in the installation—as the subject of the projected video, Gliss (portamento), in which we see him speed skating on a rink upstate.

Kaur: It started with the sound. The sound you hear is a loop of Indian classical drums that I made as a translation of the rhythm of my brother’s ice skates into a more complexly layered drum beat using Ableton. I was trying to understand the rhythm and why that was so important to my brother, because he describes his skating rhythm as an extremely important thing, but it was really abstract for me. I wanted to understand his movement with another bodily thing, which to me is sound. Sound feels parasitical in the way it puts something else within your body.

Repetition is also something I’m always interested in. I’ve always made three-minute loop videos or looping sounds. I like for it to seem like there’s no beginning or end—then the video can become more like a sculpture.

Drew: Has your brother seen it?

Kaur: He’s seen the video. And he’s seen pictures of the show. He was like, ‘Whoa!’ He was excited by watching his skating, but he was like, ‘Oh, I’m not doing well in that one part.’ It’s funny. I was like, ‘But do you like your skating here as an art?’

“I like talking to people who are obsessed. I feel obsessed with their obsession.”

Drew: In sky, harp, his skating becomes not dissimilar to your glassblowing, or even drawing or writing, where these very embodied things get distilled as aesthetic gestures. What do you think skating is to your brother? Where do you feel like the skating figures in his life?

Kaur: He’s obsessed. For a bit he had moved from Toronto to Calgary to skate. They have an Olympic-size oval that’s public access. And he was teaching physics. I feel like there’s probably more of a community of ice skaters there. To him, it’s a spiritual practice.

Drew: Is there a spiritual relationship in this for you?

Kaur: I’m not trying to go to church necessarily, but I like talking to people who are obsessed. I feel obsessed with their obsession. Actually, drawing and making stuff is completely spiritual to me. I don’t picture a guy in the sky telling me to do it, but I feel an unavoidable pull. I’m compelled to follow it.