The novelist and the filmmaker talk Oakland, Basquiat, hip-hop, and propaganda for Document’s Fall/Winter 2023 issue

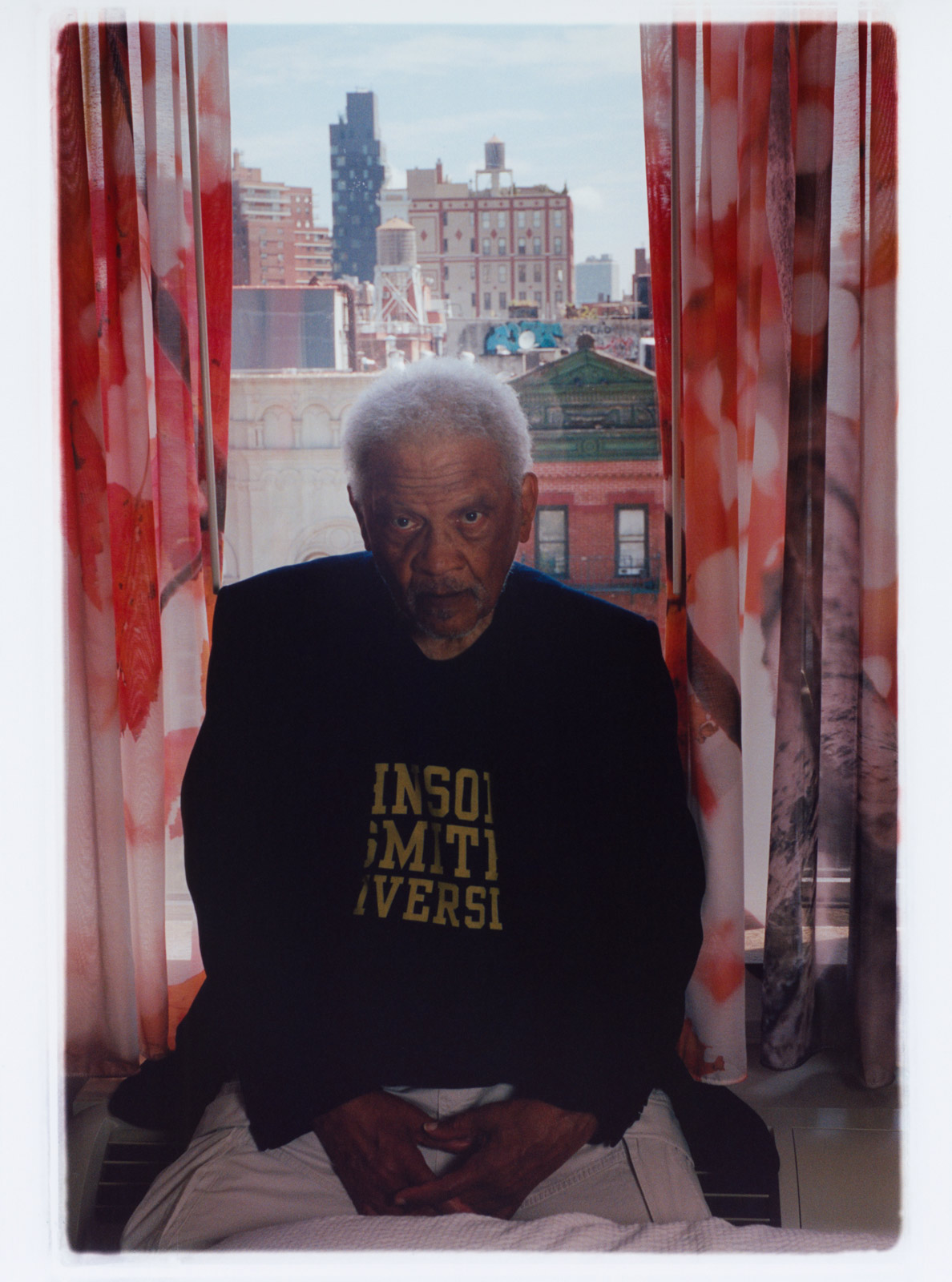

Ishmael Reed is a challenging figure. Not challenging as in unruly, but in the sense that he is not afraid to confront your beliefs, your understandings of race, money, and power.

Reed, a now 84-year-old novelist, poet, playwright, and independent publisher, has made a prolific career out of undermining hegemonic worldviews, and unearthing under-told truths with his freewheeling Neo-Hoodoo prose. His literary star rose alongside New York greats like Amiri Baraka in the late-’60s when he released his first novel, The Free-Lance Pallbearers. Shortly after, in an effort to avoid becoming a tokenized lapdog of the city’s white intelligentsia, Reed moved to Oakland to teach African-American literature at UC Berkeley. He has remained in the Bay Area since. His West Coast outpost has been the production site of a seemingly endless bounty of works: Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down (the madcap cowboy novel so ingeniously zany it is said to have inspired the Mel Brooks film Blazing Saddles) and Mumbo Jumbo (a satirical deconstruction of the Western canon), and the groundbreaking avant-soap opera Personal Problems (which was directed by the late Bill Gunn and restored by Kino Lorber in 2018), to name a few.

Reed still agitates in his late career. In 2019, he grabbed headlines for his Hamilton polemic, The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda—a play in which the creator of the popular musical is visited by spirits of the Native American and African slaves who were victimized by the very men the Broadway hit celebrates. In a similar spirit, The Slave Who Loved Caviar, Reed’s two-act play exploring Andy Warhol’s purported vampiric relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat, completed a run at the East Village’s Theater for the New City last year. Reed’s is often the first and loudest voice calling bullshit. He doesn’t accept simple answers because he knows that the truth is rarely simple. This persistent skepticism is a necessary piece of the ongoing vitality of his work. It’s also a quality that has shaped the voice of creative descendants like Boots Riley.

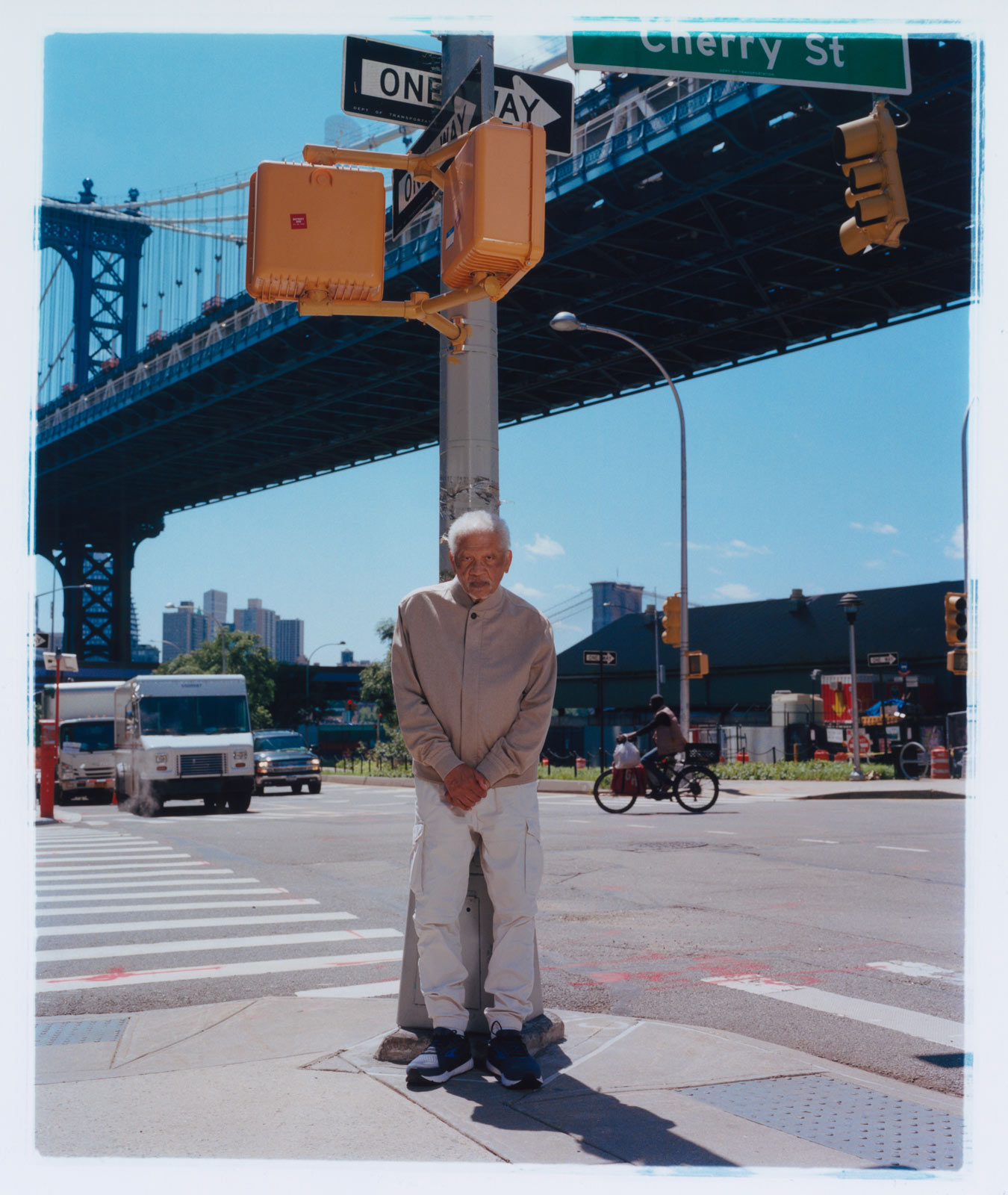

An Oakland native who has been making art and organizing since his teens, Riley is a singular voice in entertainment. Over two decades as MC and producer in political hip-hop group The Coup, and more recently as a filmmaker, his work has employed its own kind of Reedian farce. Sorry to Bother You (2018) is a surrealist satire about a Black telemarketer who, thanks to an uncanny ability to speak in “white voice,” finds himself thrust into a corporate conspiracy orchestrated by a cabal of sinister horse people. I’m a Virgo (2023) is a comedy about a Black teenager living in Oakland who is, inexplicably, 13 feet tall. While his work leans into the fantastical, Riley’s stories find their grist in real-world dynamics and material conditions of everyday lives.

The pair met to discuss, and occasionally spar on, topics ranging from the misnomer of the recent “50 Years of Hip Hop” celebrations to Richard Pryor to making socialist art under capitalism.

“Get up in the morning, read the newspapers, and get angry.”

Ishmael Reed: We closed a couple of weeks ago, but the African-American Shakespeare Company did a reading of my play about the relationship between Basquiat and Warhol. I did it from Basquiat’s point of view. It’s quite obvious that his exploitation resulted in his death. So we had two lawsuits threatening us from the Andy Warhol Foundation.

Boots Riley: A lawsuit based on what was said in the play?

Ishmael: The lawsuit was based on a flyer that I transformed, [which is ironic because] Warhol’s whole thing was transforming. He transformed that photo of Prince, the photographer sued, and the Supreme Court sided with her. I took a photograph that Warhol made of Basquiat in a jockstrap; and over the body of Basquiat, I put leeches, because he has paintings called Leeches. Inside each leech, I placed Andy Warhol’s face. They got upset. They [put on] this Broadway play called The Collaboration, and the intent was to clean up Warhol’s reputation.

Boots: Do you know where else they had collaborators? Nazi France.

Ishmael: Absolutely. The producer and director were talking about a collaboration that Warhol and Basquiat did. But Basquiat said he did all the work and Warhol was lazy.

Boots: I have a song called ‘You Are Not a Riot (An RSVP from David Siqueiros to Andy Warhol).’ It obviously isn’t real, but it’s just a diss of Andy Warhol and the idea that he sold through his art.

Ishmael: In I’m A Virgo, you’ve got this giant—13 feet tall—and he represents all Black men, as far as I’m concerned. Because that’s how society views us, in some kind of exaggerated way. One of [Stanley Crouch’s] explanations for police brutality was that the police think of every Black guy as Sugar Ray Robinson or Muhammad Ali. To the American public, we’re really outsized and freaks.

Boots: There are a lot of different ways to look at it, but that is an overarching theme for me. In [making work], I’m thinking, How do I get to people? I want to get past the idea that there is a way to [avoid] co-optation. There is some sort of bending or adherence to the system that we’re in.

You’ve also produced some movies, right?

Ishmael: Just a couple, but I’ve been publishing books since 1974. [This was when] Steve Cannon became a legend: After his death, he received a lot of publicity as the emperor of the Lower East Side [for his] organization called Tribes, which was a coalition of writers, poets, and painters. We put up some money to publish a book by Alison Mills—Hollywood wanted to make her into the Black Marilyn Monroe. She was rising as a star in Hollywood until a producer exhibited himself to her, and she left. We published her book Francisco. Her husband was Francisco Newman, who worked for KQED TV. He bought a [movie] option to what I call my Hoodoo cowboy novel Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. Then, Richard Pryor came to Berkeley and read it. Francisco bought the option, Pryor said he was going to film it, and instead, he took it to [the people producing] Blazing Saddles.

Francisco, the novel we published, is about the betrayal of Richard Pryor. In it, the people at the studio and Mel Brooks were reading my book. The poetic justice comes when Richard Pryor wanted to star in Blazing Saddles and they nixed that. But about a month ago or so, New Directions republished that Francisco by Alison Mills, and it made the front page of the Washington Post.

What your generation represents is a revival. What makes your stuff unique is that you’re giving a fresh angle on these things—a cross between satire and science fiction—that lifts Black film out of the rut. I’ve been looking at Tyler Perry, and people scoff at him. He’s just doing soap operas like everybody else. He employs a lot of Black actors, Black crew, and everything. It’s not my taste—though I enjoyed All The Queen’s Men and Zatima.

Boots: There’s nothing worse about [him] than all the other streaming stuff that I see—and I include my work in that. I think the proliferation of streaming shows changes how [people] consume everything else. To me, it becomes less like art, and more like a soap opera. I don’t remember who [said it first], but it’s not about the notes you play, it’s about the notes you don’t play. With TV and streaming, it’s like there are no notes that people won’t play. When people glom onto Black culture whether it’s through music or other forms of art, they also see themselves as trying to get away from the confines of the system they’re in. There’s a connection to Black folks that has to do with the fight they want to be connected to, because they also feel that they’re in a fight.

They keep talking about the 50th anniversary of hip-hop which I think is bullshit. When hip-hop got on the radio, no Black folks said, ‘What is this newfangled thing?’ You got stuff from the ’30s that sounds just like early rap—Pigmeat Markham in the ’60s with a top 10 song that [sounds like] hip-hop. In the late-’80s, early-’90s, a bunch of folks started getting gigs, speaking at universities. They started this narrative that had more to do with owning this thing than its [connection to] Black history—disconnecting it from that just makes it easier to market.

Ishmael: Mumbo Jumbo says that there’s something about Black culture that causes mass hysteria. Whether it’s rock and roll or wokeness, you can identify different forces that send people into conniptions. You can find traces of hip-hop in the Yorùbá classic Igbó Olódùmarè (The Forest of God). Wole Soyinka has a translation that I recommend. Unlike what they say in the Western press—where they attribute Nigerian religion or African religion to animism—Nigerian religion [centers] one God, Olódùmarè of the heavens. He’s the owner of the heavens.

Now, what hip-hop is, is the ‘toasts.’ Nobody knows why they call them toasts. But you had the signifying monkey, which is rhyme—like hip-hop, you have, ‘Shine swam on’ [from the Black folk song ‘Shine and the Titanic’].

“Whether it’s rock and roll or wokeness, you can identify different forces that send people into conniptions.”

Boots: Yeah! ‘Get your ass in the water and swim like me.’

Ishmael: That’s right. And hip-hop added sophisticated audio equipment to this old tradition. ‘50 Years of Hip Hop’ is a marketing term. It’s the branding, but it has nothing to do with Black history.

I went back and read Dust Tracks on a Road, Zora Neale Hurston’s 1942 autobiography. It has rock and roll in it. Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone was born in 1946, yet he poses as the expert on rock and roll—just like [how] a lot of outsiders see themselves as experts on hip-hop.

Boots: Right now, we do have some things that are considered Black outlets. But some of them put out the same line that the other capitalist outlets do.

Ishmael: You have to be careful about these Black outlets, because the money behind them might not be Black. We published a novel called Love Story Black by one of the most neglected Black writers of the last hundred years, William Denby. He writes about a famous Black magazine—the capital behind it was not Black. You have to be careful about certain magazines that have marketed themselves as Black. The FBI has been following Black writers at least since the ’20s.

Boots: The CIA famously started The Paris Review.

Ishmael: James Baldwin’s attacking Richard Wright—that was a hit that had nothing to do with literature. Because the guy who ran Partisan Review hated Richard Wright. And so Baldwin picked up that thing and wrote ‘Everybody’s Protest Novel.’ There’s a paucity of outlets. That’s why it’s up to you…

Boots: I only got a certain amount of movies in me before I gotta tap out. And writing, as you know, can be very isolating work.

Ishmael: I got the blessing, I got the music. I take a walk at 3 p.m. and start communicating with the birds.

Boots: Tell me about that. What’s a writing day like?

Ishmael: Get up in the morning, read the newspapers, and get angry. I get up at 6 a.m.

Boots: Do you have a certain time that you start writing? Just whenever it hits you?

Ishmael: Well, I avoid writer’s block because I work in different genres. So if I get stuck in poetry, I’ll go to prose. Get stuck on that project, I go to op-ed. I write a whole bunch of op-eds. But see, the problem is, I have to go to Spain or France to get [them] published. My latest was published in El País, Spain’s leading paper, because my opinions [are] a little bit too thorny for American publications.

Boots: I have three movies that I wrote, while I was making I’m a Virgo [in New Orleans].

Ishmael: You’ve talked about the costs of doing a film in New Orleans, and doing a film in Oakland. I thought that was a very important point.

Boots: The reason they give 25 percent back to the entertainment industry is because they made a deal with the oil industries in Louisiana: In exchange for that 25 percent, they get huge tax breaks that would have been worth so much more money to the people of Louisiana. That’s why you can drive through New Orleans and get your car stuck in a pothole. They don’t have infrastructure there even though they got these billion-dollar oil companies. This was one of those compromises that early on, I gave in on.

“We’re all putting out ideas, right? Whether it’s directly government propaganda, or we’ve already been brainwashed and put out propaganda for them.”

Ishmael: What about Oakland’s attitude toward filmmakers?

Boots: The main thing that keeps artists moving away is the rent. You want to keep artists, you gotta have some real rent control. The other thing is, the rent being high also makes pay have to be higher, because it costs a lot more just to live here. There are some plays to make a city rebate where they’ll give you $800,000 of city expenses back. So that ends up being a line item that can make budgets go down. But [there are] not a lot of people shooting in San Francisco either.

Ishmael: The problem with capitalism is that it runs things. It’s out of control, and nobody knows how to put a clamp on it. It owns Congress. It prefers profits over the survival of the species. The oil companies, for example, make $9 billion in profits because of COVID. They made money off disaster. I’m not the first to say that. Take William Wells Brown, 1854, who was way ahead of me, in terms of being a Black satirist. He wrote a play called The Escape; or, a Leap to Freedom, where these doctors hope that the smallpox epidemic will come to their towns, so they can make some money.

I see a lot of propaganda. And I fight against it. I fight against propaganda in the United States every day. But I have to go abroad to get my comments published.

Boots: I agree with the villain in [I’m a Virgo] that it’s all propaganda. We’re all putting out ideas, right? Whether it’s directly government propaganda, or we’ve already been brainwashed and put out propaganda for them.

Ishmael: And Boots, you’re being produced by Amazon, which is maybe the biggest capitalist outfit in the world. You can talk about the glories of communism, but you’re in the system. too. We all are.

Boots: Yeah, I know! I’ve said that from the very beginning.

Ishmael: If you believe all this communist stuff, why don’t you disassociate yourself from Amazon?

Boots: I’ve used EMI, which was a major corporation. I’ve used Warner Brothers. I’ve used all of these things to get my stuff out. I’m not asking anybody, through my art, to disconnect themselves from capitalism. I’m asking for them to organize on their job, to help form a mass militant radical labor movement that uses the withholding of labor as a tactic to effect change.

Lighting Technician Josua Jimenez.