How a loose cohort of international writers opposed the status quo, pulling from the endless subjectivity of culture to produce some of the century’s best literature

Today, there seems to be a trend in literature that decries its exhaustion—no one reads anymore, they say, the literary golden age has passed—while at the same time, novels with identical covers and similar themes are being churned out. They sit in their pastels and millennial fonts, smug in the storefronts of McNally Jackson, etc. There is anxiety around the “identity” novel, which makes understandable and citable the experiences of minorities and working-class people. On the other hand, the avant-garde city novel sinks into the comfortable malaise of New York City neuroses and Internet-oriented clamor.

In her 2021 novel Beautiful World, Where Are You, Sally Rooney gives voice to the anxiety at the heart of contemporary literary culture. Two of the protagonists—one an outcast who has reached sudden success as a writer, and the other a repressed editor at a literary magazine—exchange a series of letters detailing their daily lives, interspersed with musings about the state of the world: from capitalism’s unfettered destruction to the pointlessness of fame. The existential concerns they express are common, almost normal (something horrible in itself). And they’re supposed to be; the novel is both easy to read and relatable to the professional artist class, and those who aspire to it. It’s done well. It’s comfortable.

She laments the normalcy of writers, and at the same time complains about the pointlessness of writing at all when so much suffering exists in the world. That to write protagonists moving amongst suffering would be tasteless. In one passage, the unlikely author writes to the other that, “The problem with the contemporary Euro-American novel is that it relies for its structural integrity on suppressing the lived realities of most human beings on earth.”

The point on normalcy and poverty is a strange one, considering the amount of literary production that happens outside of the Euro-American novel—never mind the strange world of experience that happens everywhere—especially in the digital age. But we shouldn’t take this stance as Rooney’s (the character is particularly self-degrading), nor should we really care. At the very least, the passage and the book represent a certain kind of writing—the self-referential, the autofictional, which does not mean veiled autobiography. Serious works of autofiction are, after all, usually books about people who write books.

This whirlpool of Euro-American pomp and dread has affected me, too. Especially during the pandemic, when the point of literary production seemed irreducible from the assumption that, at the end of the day, all of our lives were small and our imaginations limited. In that haze, I stumbled upon novelist Dennis Cooper’s review of the collected writings of a group who called themselves the Neo-Decadents. Little else had been written on this loose cohort, not least of all because of their commitment to print and the fact that their primary Internet hideout lives under the geriatric ruins of Facebook, far from the hip circuits and big presses.

But actually reading their work and engaging with some of those involved changed my outlook on the potential of contemporary literature.

“Who doesn’t want to get away from the malaise of the deep thinker who whines for a whole book about their writerly problems—the same old New York filth and Parisian philosophy?”

I read through the novels, short-story anthologies, and other books, and began talking with some of the writers. They are based all over the world, though they shy from big, “hip” cultural capitals like Paris and New York. Justin Isis, who edits many of the collections, works as a club promoter in Tokyo and lives in discernment and excess, while others are shut-ins or menial workers or mountainous teachers or addicts, from Romania to Peru.

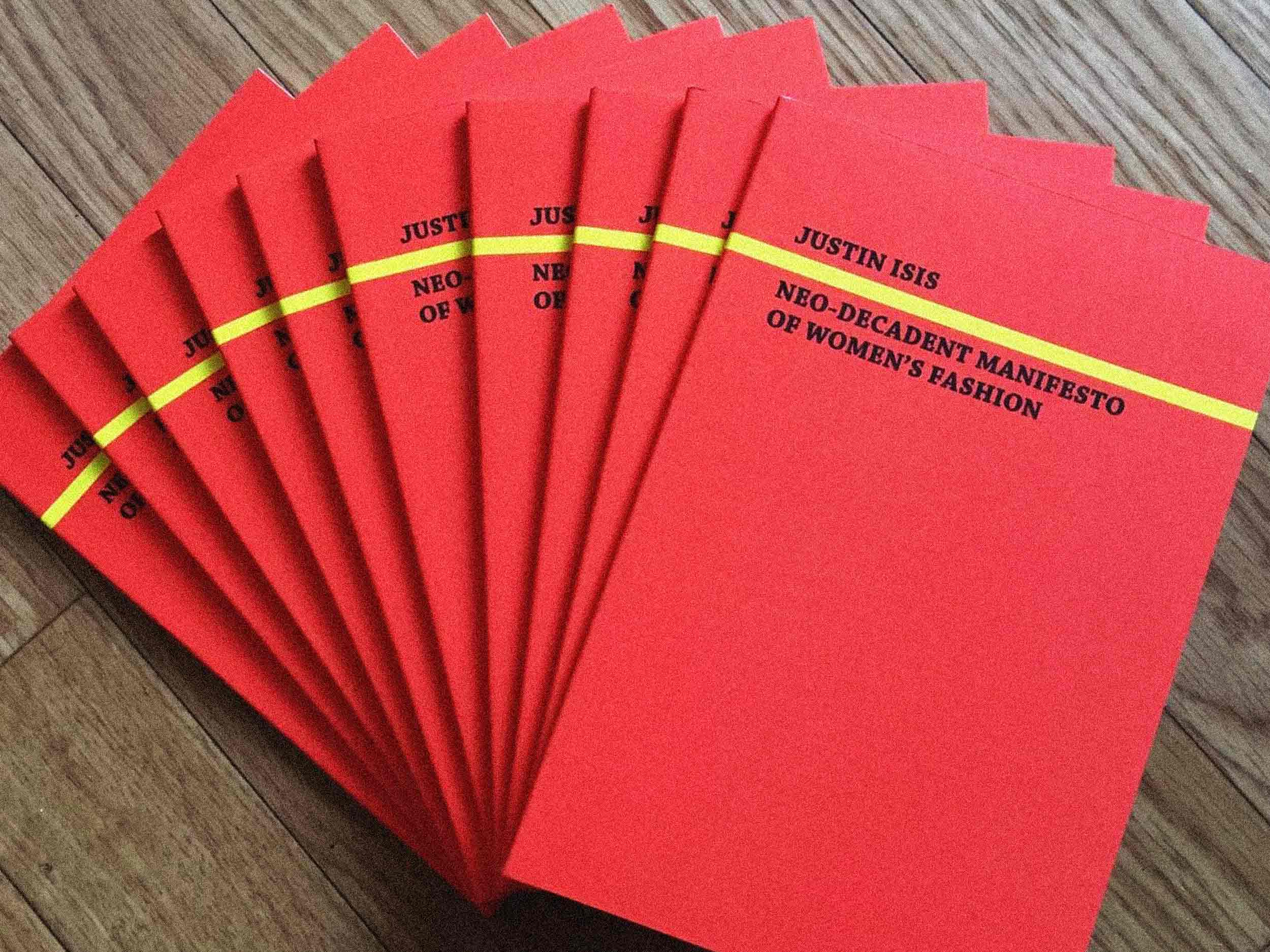

In a series of manifestos, Neo-Decadence is laid down in vibrant, sometimes-nonsensical, instructive, and often-insulting propositions: These documents present general overviews as well as specific takes on fashion, architecture, poetry, electronic gaming—even personal relationships and nature. Many are written by numerous people, some co-authored and some individual, and all organized through Isis’ deft vision

While some of the statements are bizarre, they don’t come across as edgy. Others, like “Great developments don’t come about by listlessly trying to please the crowd,” written by Brendan Connell, who coined the term Neo-Decadence in 2010, seem more concerned with beauty in extremes and commitment to creation than with the manosphere or clicks.

Stylistically, many of the works embrace the Internet and genre fiction (sci-fi, horror) without falling into easily categorizable features or made-for-movie habits. Neo-Decadence rejects moralizing tales and the idea that the reading of anything makes anyone more righteous or politically pure. It also dismisses easy notions of the apocalypse, embracing futurism, while acknowledging that we already live in an apocalypse of everything that came before. It cleaves to the high taste and specificity of the dandy but balks at the museum; “the Internet is more beautiful than a cathedral.”

The movement, at least in the manifestos, positions itself against a specific style and way of living: what they call Neo-Passéism, a type of writing produced in professional circles that is the “unexamined artistic logic of capitalist realism.” In fact, in the manifestos, there is an entry called “Against Neo-Passéism,” with 49 propositions that talk shit about anything relatable, thoughtlessly transgressive, or overly commercial. Its five authors even go so far as to say that all the literary movements of the 21st century are already passé.

The Neo-Passéist—the characters in Rooney’s novel being paradigmatic—and the Neo-Decadents are confronted by the same problem. All writers are. The complexity of the world means that you can spend your whole life trying to navigate the writer’s scene—even just in a place like New York. It’s not a deep statement: There are so many people and there’s so much to discover. One could go their whole life moving through the world of writers that huddles around the supposedly dimming flame of literature in urban cores.

While not all of the work of the movement stays perfectly within the stylistic lines the manifesto lays out, the sheer bulk of its accusations and self-aggrandizement gives all of the associated literature an aura of assuredness. It comes as a welcome answer to the navel-gazing New York novel, the hazy bucolic nothingness of indie film, and the conservative wailing of transgressive punks who flail against nothing in particular and everything at once.

“Neo-Decadence may seem like just another anti-art, but it goes beyond opposition and glorifies the complete.”

What’s most refreshing about the literature is that writers rarely feature in it at all. In one of Isis’s short stories for the collection Drowning in Beauty, a Japanese nail artist strives to perfect her work in the language of a rigorous philosopher reaching an insane, aesthetically-derived vision of the nature of reality. Another, by occultist and author Damian Murphy, presents an arcane story in the style of a pick-your-own-adventure video game. And while the works have so far been mostly written in English, there are Neo-Decadent “cells” in Latin America.

We don’t necessarily need any more diagnoses on the stagnation of older forms of art, like the traditional novel—and we certainly don’t need to do the world the condescending disservice of repeating, ‘No one reads anymore.’ But diagnosis and shit talk paired with a bounty of suggestions is generative, and just feels good and fun, like manifestos that declare the Fashion Week show a solemn church service, animals as passé for not having invented plastic surgery, and the “indisputable” importance of gloves…

Who doesn’t want to get away from the malaise of the deep thinker who whines for a whole book about their writerly problems—the same old New York filth and Parisian philosophy? Instead, we can read about the psycho-sexual adventures of a girl in Tehran, like in Golnoosh Nour’s story “SadPrince” from the Isis-edited collection Neo-Decadence Evangelion. “Unlike most of my acquaintances and relatives, I don’t have to leave my country for my dreams to come true. My dreams are beyond the superficial notions of Western success,” her character muses.

In the same collection, Arturo Calderon mixes the language of the web with hip-hop, Incan mythology, anti-American revolution, and full paragraphs written in Spanish. Countless pop signifiers, emojis, and obsessions are casually linked with cultural events and science and animal totems, with Peruvian university girls acting as the main character.

Other art movements in New York City seem to be coming to the same conclusions, forsaking workshops and self-referentiality for the endless subjectivity of culture, under the sign of the internet. Writers like Michael Bible, with his bizarrely mythic tellings of the diurnal, or Olivia Kan-Sperling’s stylistic inhabitation of celebrity voices are pushing past writing about our brains on the internet, instead harnessing the full array of influence available to us.

Neo-Decadence may seem like just another anti-art, but it goes beyond opposition and glorifies the complete: From “pleasant tales” that have no conflict to blasted post-industrial worlds, the settings encompass the mutated richness of the planet and beyond, with well-deserved pomp and imaginative, truly avant-garde talent to back it.