In her biweekly column for Document, McKenzie Wark attends a Suzanne Ciani concert, and gets thinking on information theory and control

I know very little about music other than that I love it. I especially love hearing new things. Or, at least, new to me. Suzanne Ciani is a legend among electronic composers and performers, but a recent discovery of mine. Somehow, I missed a lot of the pioneering work in electronic music. It seemed like a marginal endeavor. The funny thing about the avant-garde is that it sometimes skips the middle and connects to the most mainstream dimension of culture. And so it is with Ciani, who composed one of the most widely-heard pieces of sound art ever, the Coca-Cola “Pop & Pour” used from the late-’70s onwards in countless commercials.

Another thing about avant-gardes is that, no matter how much they want to revolutionize art and life, they can be even more retrograde on gender politics than the mainstream culture. The work of Suzanne Ciani might have been much more widely-appreciated were it not for that boys’-club mentality. All the same, she has created an extensive oeuvre, documented across more than 20 albums since 1970.

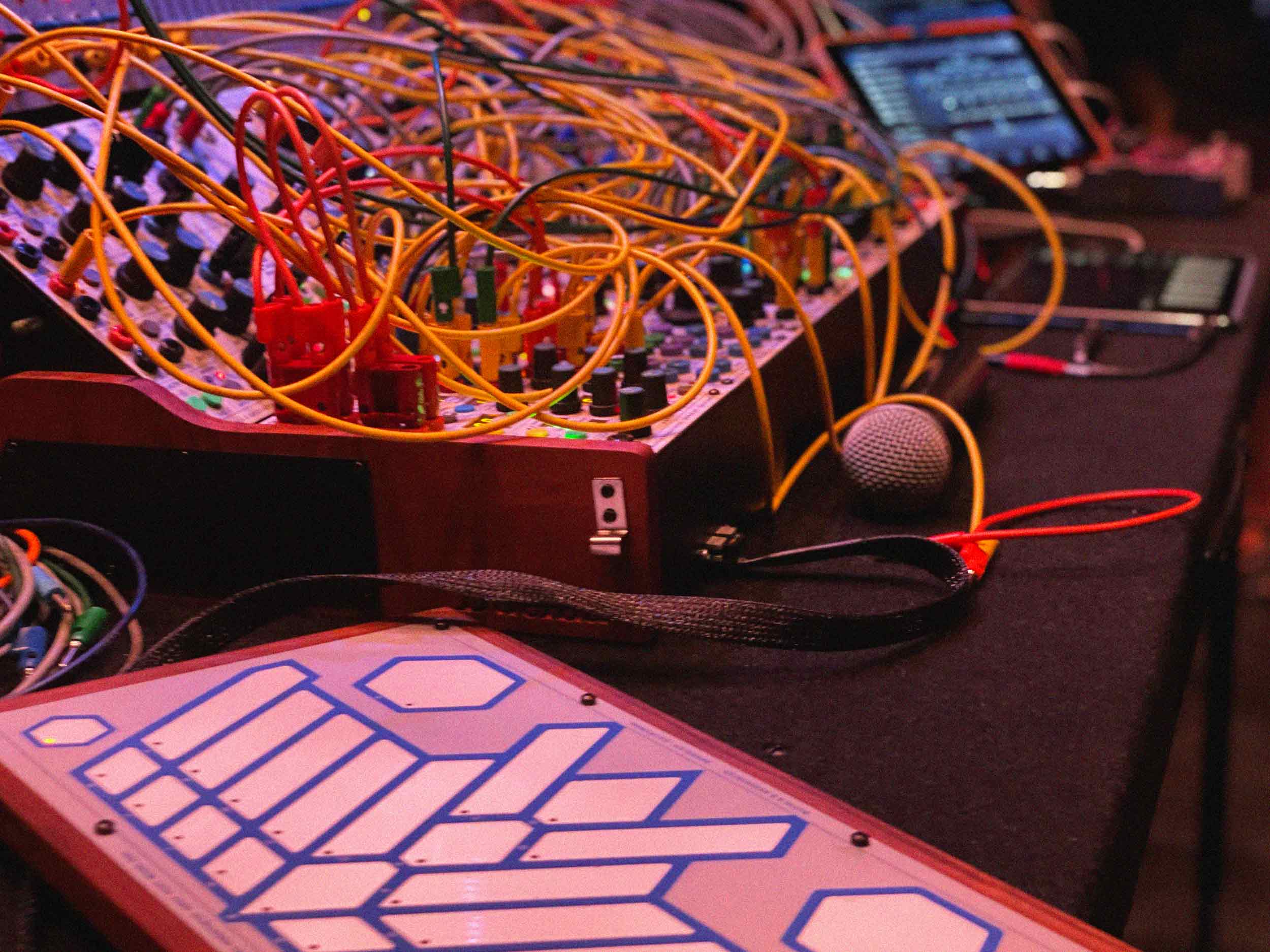

Much of her work employs the Buchla synthesizer, versions of which have been in production since 1966. When my friend, the electronic composer and instrument-maker Gavilán Rayna Russom, offered to get us list for a Ciani improvisation on a Buchla 200e, I jumped at the chance. The performance was part of MoMA’s Studio Sound series, in the Kravis Studio.

We took the elevator up a few floors to find a beautifully appointed performance venue, set up on this occasion with seating in the round, with Ciani in the middle. Neither of us recognized anyone in the audience. We’re both Brooklyn bitches, I guess. Most of the electronic music I hear is in bars and clubs. I wonder about the role of art institutions as doing the last parts of the work of distilleries—the distillation and the aging. The early part, the fermentation, happens elsewhere.

The audience recognized Ciani, however, and gave her a warm reception. We were seated in the part of the circle facing her; on the wall opposite was a stream showing her Buchla, so we could watch her hands at work. As sound filled the room, I closed my eyes.

“I wonder about the role of art institutions as doing the last parts of the work of distilleries—the distillation and the aging. The early part, the fermentation, happens elsewhere.”

Quadraphonic sound has its own pleasures. It has its own shape—sculpted from shivering air, moving across the room, sometimes diagonally. Some movements had a low-frequency, rhythmic pulse, bordering on techno. Ciani’s relation to the machine had such a beautiful intimacy. This was the sound of analog synthesis. A way of thinking and breathing with sound that treats it as multiple parameters which can vary and interact in time. It’s not just a sound—it’s the concept of that sound.

You wouldn’t know from listening, but watching Ciani, I felt there was a moment of improvisation where the Buchla was pushing at her, rather than her at it. After the performance, she explained that two of the envelope generators had stopped working. That’s the nature of an art of complex systems—parts might go down or behave in weird ways.

Ciani also expressed her love for the Buchla as a synthesizer that provides feedback to the artist as they improvise. Both the synth and the late Don Buchla (its inventor) have a temperamental, quirky side, but there’s a philosophy here which might say something in general about engines of creation. One where the keyword is not control, but feedback.

Early information theory had a lot to say about feedback. Maybe it’s a concept worth picking up again. Feedback is the output of an information system which has the ability to change that system itself. In this case, the information system is Ciani plus the Buchla. The device produces information about itself to which the artist responds in real time.

The simplest model of feedback contrasts the positive and the negative. Positive feedback is where the information produced by the system—about itself—accelerates some aspect of it. Negative feedback is when that information induces the system to reduce something.

A famous example can illustrate both: Jimi Hendrix playing not only his guitar, but also his amplifier and speaker stack. By standing close to the speaker, its sound enters the pick-ups on his guitar as signal, feeding back into the amp and out again, initially as a runaway positive feedback loop, generating more and more noise.

It’s also an example of negative feedback. Hendrix is part of the information system. Listening to the sound, he moves his body to moderate its intensity, moving the guitar away. And then—next level shit—becoming a guitar-guitarist-amp-speaker information system that plays not guitar, but guitar feedback.

“In building an information system on the principle of control, we ended up with one that is out of control. Or if there is control, it is no longer by humans much at all.”

Just a year before Hendrix played Woodstock, Douglas Engelbart recorded what is known as “The Mother of All Demos,” which demonstrated to the public many of the features of what would become the contemporary computer interface. You could think of it as the beginning of the simulation of feedback. You move your hand on the mouse, and it looks like you move things on a screen. The visual lets you regulate your movements in relation to the machine, but it no longer tells you anything about what the machine is doing.

One way that I think about contemporary aesthetics is to ask whether it is attentive to the question of what happens in feedback loops that include both humans and machines. These days, I wonder if there was a wrong turn in the embrace of digital machines, which simulate feedback but cut us off from understanding what actually happens on the inside.

One of the beauties of analog synthesizers is that, with some basic understanding of electrical engineering, you could have an idea of what the machine part is actually doing, even if it still produces unexpected feedback. You could learn with it, play with it, explore it. Digital synthesizers can simulate that and more, but they introduce a separation between the simulated feedback loop and the machinic processes themselves.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, other than that, allegorically, it would seem that we’re all now trapped in simulated feedback loops with machines we don’t really understand. Or to step the allegory up a level: that the whole global information economy is one enormous positive feedback loop, accelerating noise that will blow out the planetary sound system soon enough. In building an information system on the principle of control, we ended up with one that is out of control. Or if there is control, it is no longer by humans much at all.

What I hear in Suzanne Ciani is another aesthetics of technology, of human-machine feedback loops. One supposedly rendered obsolete, but which was probably pointing towards a more enduring philosophy. How the human-machine information system might be one in which feedback isn’t just simulated—in which the human and machine can make the most surprising music together.