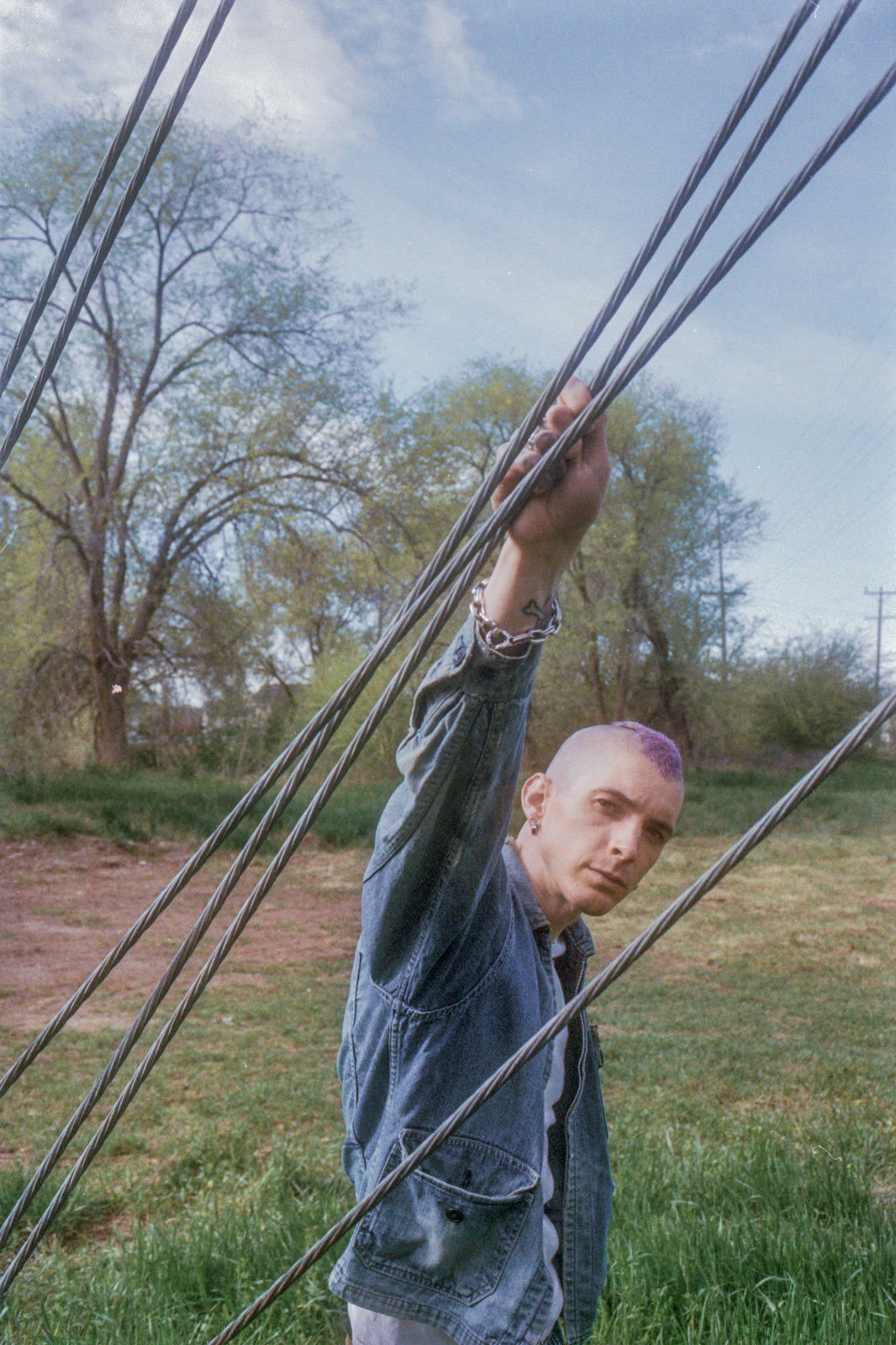

Ahead of the release of ‘Heaven Is a Junkyard,’ Trevor Powers joins Document to discuss dogs, God, names, and music

In its simplest form, a name is a point of reference. But whether it’s assigned or self-appointed, it’s endowed with conceptual import—often so much that it becomes a point of identity. This was the case for Trevor Powers—whose artist pseudonym he assumed became too weighted with meaning, eventually mutating into something that no longer felt like a piece of himself. In a trilogy of albums, Powers had built up a form he no longer wanted to fit into; an identity he no longer wanted to identify with.

Seven years ago, Powers abandoned the moniker Youth Lagoon. Nothing, aside from the name, really changed: It was the same mind behind the music, only now, unburdened by its own reputation. The Boise native assumed his given name on two subsequent tapes (2018’s Mulberry Violence and 2020’s Capricorn)—experimental efforts to depart from the creative chokehold the success of his prior works had placed upon him.

It took losing his voice entirely for Powers to reconsider exactly what it was he felt restricted by. After a severe reaction to an over-the-counter medication, the artist’s larynx and vocal cords were coated with acid for eight months. Unable to speak, and unsure if he’d ever be able to again, he was left to fixate on his immediate reality: examining every detail of the physical world around him, grappling with the most tender parts of himself, considering and reconsidering every passing thought.

Powers came back into his voice with a recontextualized understanding of his creative landscape. Heaven Is a Junkyard is the product of the rigorous meditations he endured over the years in which the album started to take shape. In piecing together these songs, and his picture of himself, Powers realized that he didn’t need to sacrifice what he had built with Youth Lagoon—that, if he chose to, he could remold it to suit his more recent self. It wasn’t the name that restricted him; it was his willingness to succumb to external perceptions of what the name meant.

In anticipation of the June 9 release of Heaven Is a Junkyard, Powers joins Document to discuss dogs, God, names, and music. When we meet, Powers is running late—only by a minute, but he’s very sorry.

Trevor Powers: Sorry, sorry, sorry I’m late. My dog had surgery.

Megan Hullander: Is he okay?

Trevor: He had this mass on his side and he kept scratching it. I took him in and had it removed, but they had to open it up a lot. Poor kid is not doing well.

Megan: I feel like names are something that you’ve been contending with lately, with your reclamation of Youth Lagoon. So maybe a good place to start is where the name of your dog derives from.

Trevor: He came from a hoarding situation in The Middle of Nowhere, Idaho, where this guy had over 50 dogs, and he taped paper over the windows, so there wasn’t any sunlight coming in. He got arrested and a lot of the dogs had to be put down because they had diseases. But a lot of the puppies were able to be saved. Wilson came from that situation. And at the time, I had just seen Cast Away.

Megan: Does Trevor come from anyone or anything? Or have you posited its meaning over time?

Trevor: I think my parents just liked the name.

Megan: I’ve been following your work for about a decade now, and I feel like I’m still not completely clear on what the moniker Youth Lagoon means. How much of it is a sort of character you inhabit? Or is it really just a name you use as a container for music?

Trevor: Over the years, a lot of that has shifted pretty dramatically. When I started in 2011, there wasn’t any weight that came along with it. It felt like, going from The Year of Hibernation to Wondrous Bughouse, I was evolving as a person, I was growing as a person, I was failing as a person, I was succeeding as a person. But a lot of people wanted The Year of Hibernation Part Two, and that’s something I’d never do. It hardened me a bit to the world. I was moving on to these other things I was excited about—and it’s not that no one was paying attention. It’s just that the people who wanted The Year of Hibernation Part Two were being really almost aggressive about it.

[Working on] Savage Hills Ballroom in 2015 was a weird time for me—I had lost myself in so many different ways. When I started Youth Lagoon, I was so young, so I never really had a chance to find myself. I no longer identified with this thing that I created. I [departed from the name] after Savage Hills Ballroom, and I’m so glad that I did. It allowed me to go into these other caves of my brain, and that was such a necessity.

Megan: Why didn’t you feel like you needed to distance yourself from it anymore? What about felt like it was a continuation, and not a separate entity?

Trevor: I’d gone through a lot of personal shit when I was writing Heaven Is a Junkyard. I started working on this album about four years ago, but at the time, I had no idea what it was. It was relatively formless. I hit this breaking point where I was seeing a therapist, and he asked me to name some things I love about myself. And I realized how difficult that was. I couldn’t do it. I’ve always departmentalized things in my brain, where it’ll be like, This is who I used to be, this is who I am now, this is who I’m going to be. I had essentially let other people ruin it. When it had been only mine, there was a purity to it. I let that be taken away from me.

But I had this moment of realization: a refusal of letting that happen—a reclamation. That it was beautiful and is beautiful. How does this look when I take [Youth Lagoon] and combine it with who I am in my life now? When I fused those two worlds together, it was like, This is something totally fucking new.

“It got to the point where, when I found something snapped into place, it was like it could be written no other way.”

Megan: The way you talk about that reclamation of music is similar to the way that you talk about God, in the sense that there’s a disconnect in your experiences or intentions, and the perceptions that are tied to the name of a thing. There’s an interview where you spoke about grappling with how different your conception of what ‘God’ is from the people around you. I’m curious why, even though you don’t perceive God in its most common form of understanding, you still attach that name to it.

Trevor: I go back and forth, because whatever you want to call it is different for everyone. It truly is unnameable. And some people don’t even believe that it exists, she exists, he exists. But I can never, and will never, abandon that—because I sense God in everything I do, everywhere I go.

There’s a timelessness to that name. But there can also be baggage with it. I might have had baggage with the name when I was young. I grew up in a Christian church, I was homeschooled through eighth grade, and then I [went] to a private, Christian high school. It is a system that I was fed, and that I was raised on, and it had so many boundaries and so many bigotries. I think that was the point at which the word God [was] a boat that took on too much water, and it felt like it was sinking.

But I wanted to reclaim what that word was and not let it lose its power. I do feel like there is significant power in the word God—but I also don’t really care. I refer to God as source. Some days, it feels a little bit more accurate, because there’s not as much of a context built around it. But it’s all really saying the same thing.

Megan: Thematically, the album is very weighty, and I read something where you said that, if you’re listening to it in the background, you might not pick up its darker nature. How then, does the relationship between the lyrics and the music take form for you?

Trevor: I spent more time on lyrics on this album than I ever have on any other album. I’ve cared about lyrics in the past—it has nothing to do with that. It’s more about falling in love with the art form of words. And that felt fresh to me. It almost became an obsession, where I would go on walks and have these lines spinning around in my head, constantly seeking a better word. It got to the point where, when I found something snapped into place, it was like it could be written no other way. As soon as it felt right, I knew I had to hold my hands up and not touch it, because I didn’t want to ruin it. This whole songwriting process has really just been about falling in love with the act of writing songs. I wanted the lyrics to stand alone, enough that you could print them out without any music attached.

Megan: A lot of that darker subject matter is based on experiences that didn’t happen all that long ago. I imagine your understanding of them was still changing when you were writing about them. So how do you know that you’re expressing what you want to express, if the thing you’re expressing is at least somewhat in flux?

Trevor: I think it’s fun to play around in those areas where there’s so much that can change and will change. You have to approach it with enough confidence to write it down. But even in day-to-day conversation, there are so many things that I’ll say one day, and then tomorrow, I wake up and I’m like, What the fuck was I talking about? I don’t agree with what I said, or I don’t know what I was saying. I think that is about as human as it gets. Being human isn’t about having things figured out: It’s the act of trying to figure out, that constant state of imperfection.