Years ago, the actor requested the cinematic rights to the writer’s ‘Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi’—here, they revisit the proposal

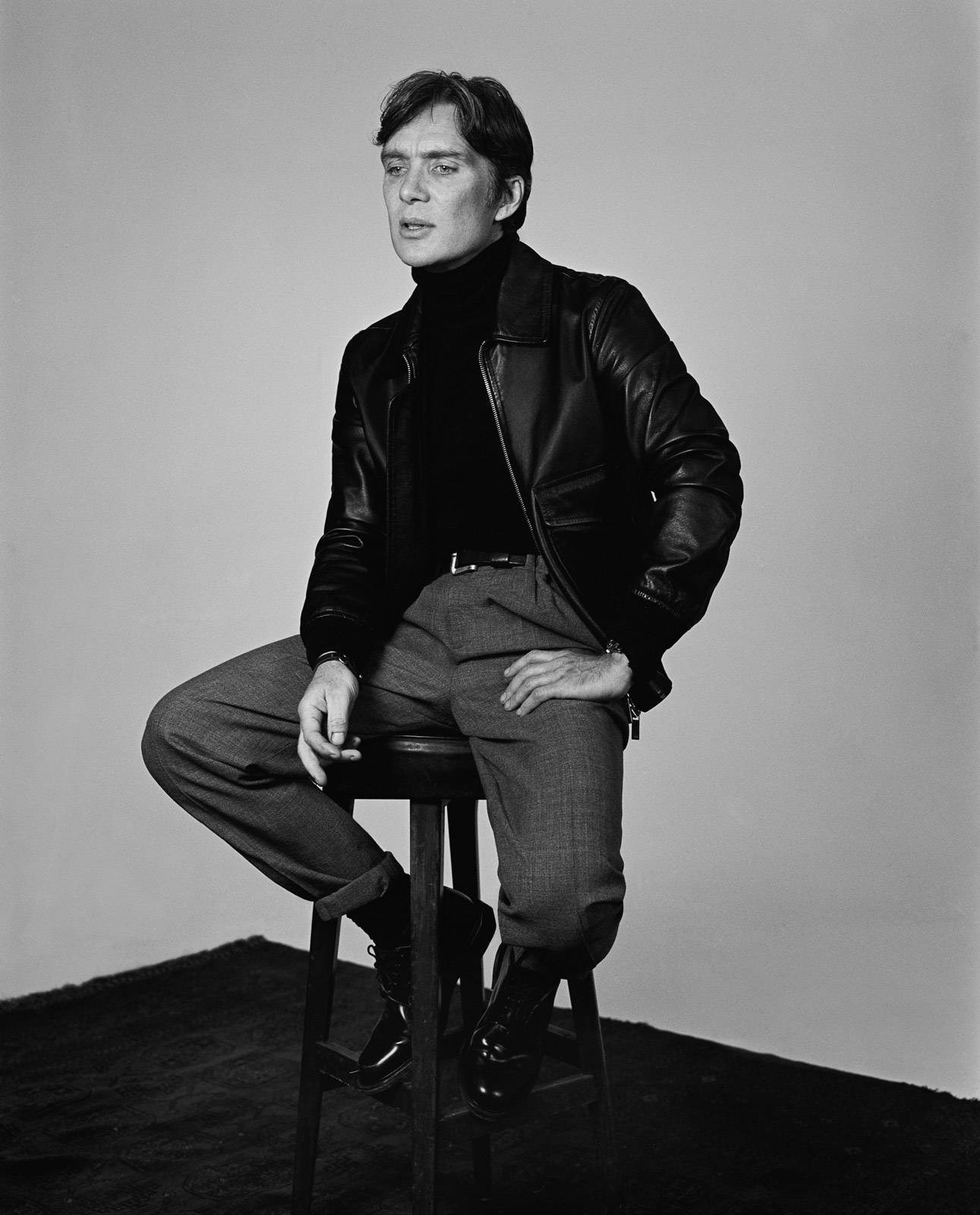

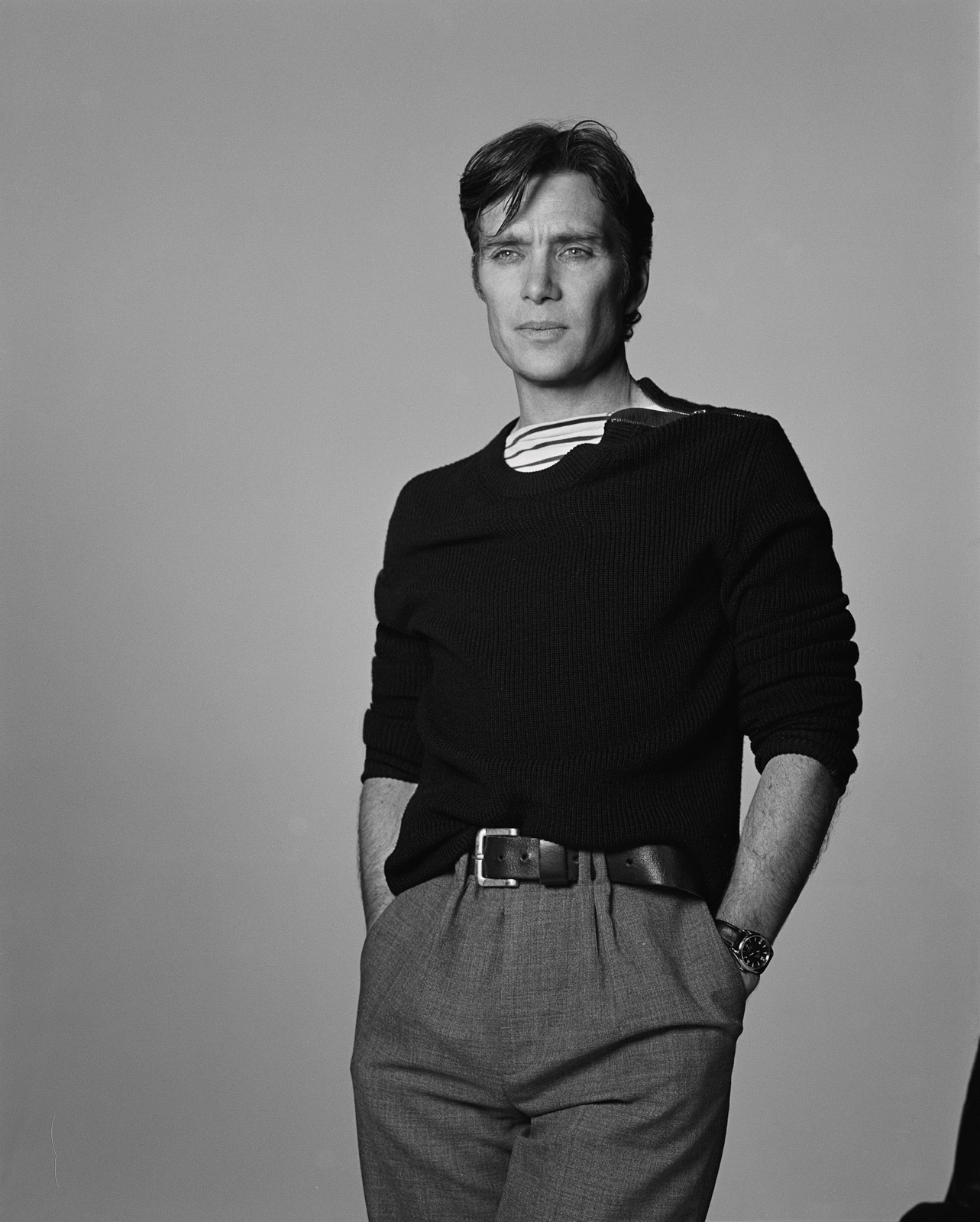

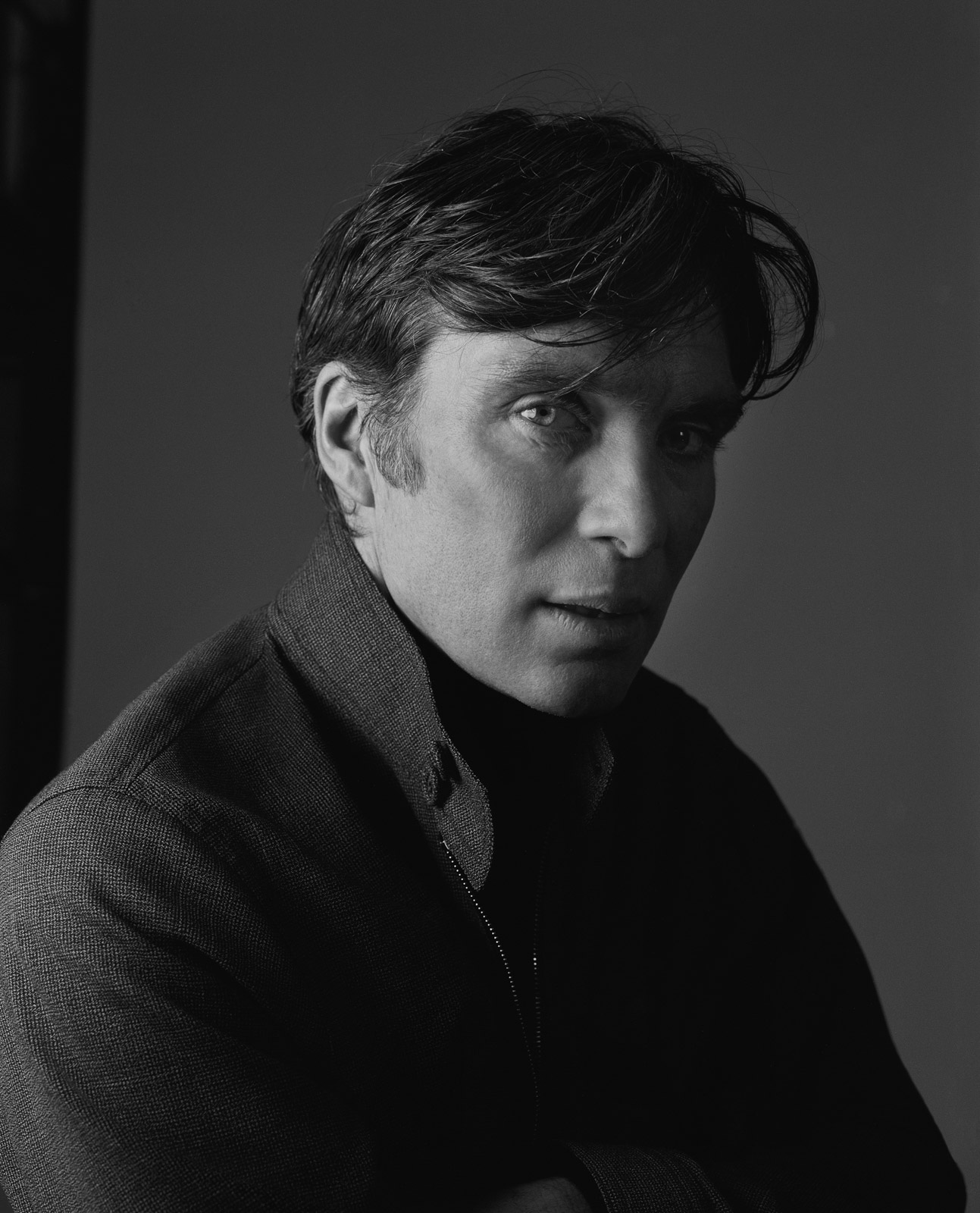

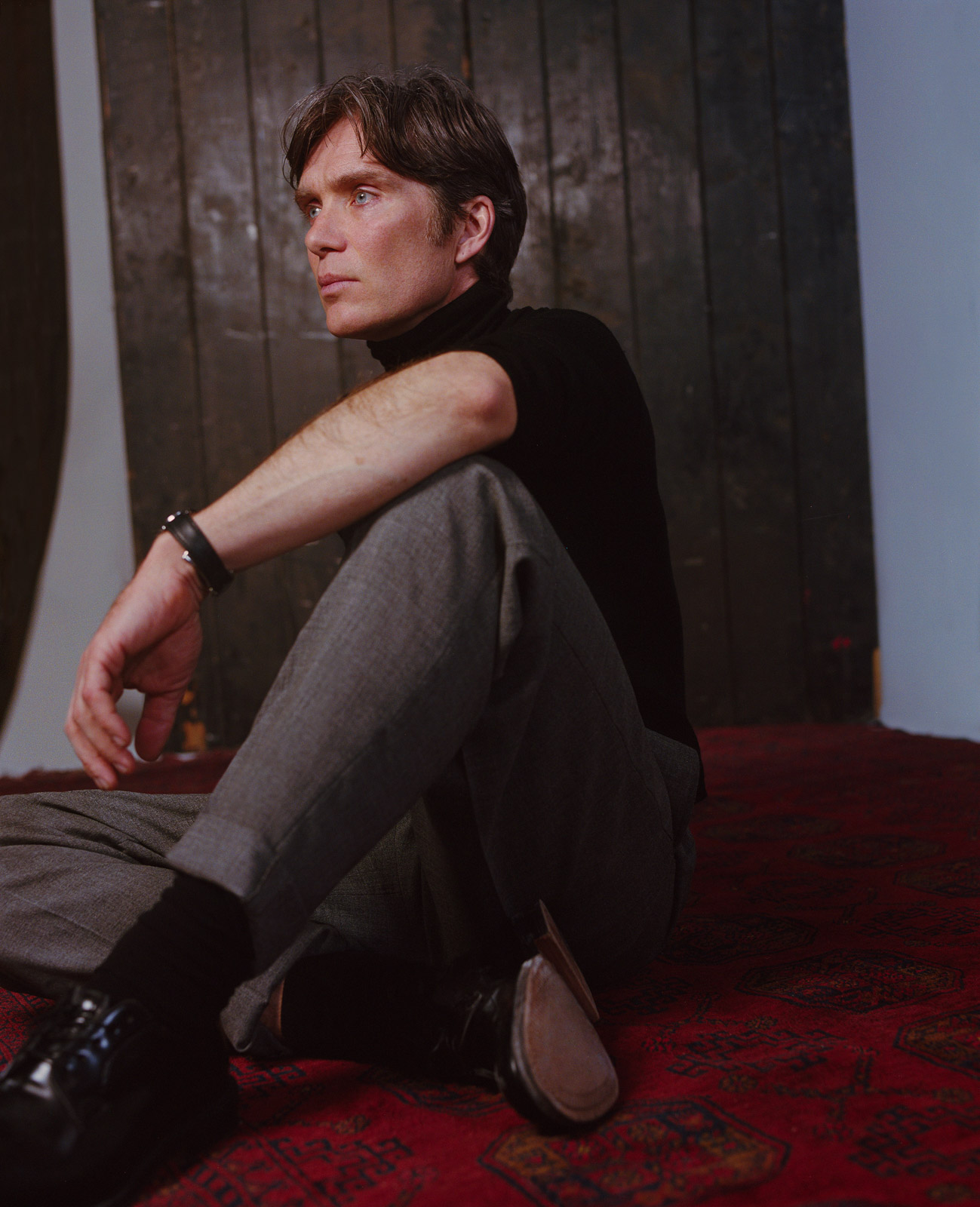

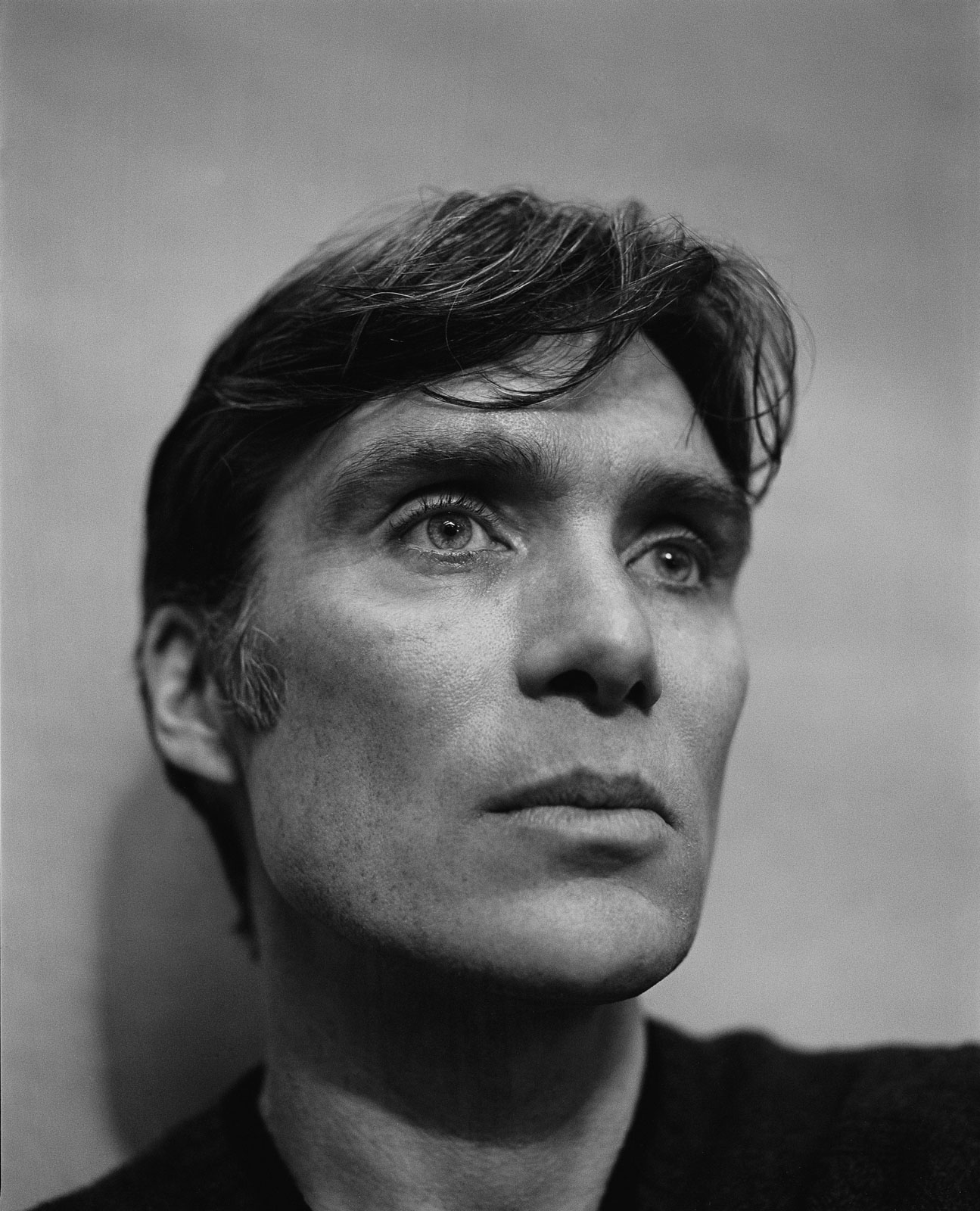

Actors, as a species, yearn to be observed. As such, Cillian Murphy is understood as a mutant among men, because, for him, that desire is contained to his on-screen self. Most of the time, he prefers the role of the observer to that of the observed—and not in the ogling sort of way that his largely (and intentionally) obscure public image is often consumed. For Murphy, it’s a more subconscious, osmotic study of behavior—one that can only be achieved by truly living an ordinary life. But the actor isn’t ordinary; ironically, it’s his lack of ordinary behavior that’s bolstered his reputation as ordinary despite being [insert exceptionally talented, exceptionally good-looking, or really any other type of exceptionality that would make the actually average person insufferable]. “I haven’t created any controversy,” he once told the Sunday Times. “I don’t sleep around, I don’t go and fall down drunk.” Things, I’d argue, an ordinary person typically counts in their behavioral history.

Where deficiencies in Murphy’s own character are observably lacking, the appeal of those he inhabits is rooted in the epistemological privilege granted to their audience which teases at their most abject peculiarities. Each of his roles is a prime embodiment of the widely claimed, rarely achieved Onion Person, the layers of whom he strategically unfurls across any given performance. This trope is perhaps most obvious with antihero Thomas Shelby in Peaky Blinders, through which Murphy, over the course of six seasons, seamlessly amalgamated a cocky criminal, a war hero, an emotionally estranged outcast, an ill-willed informant, an ideologically malleable member of Parliament, and a floundering father into a single character.

Even within the constrained time frames of film, he’s repeatedly proffered the multipronged nature of man. It’s overt in the multiple personalities of a quiet bank clerk (one of which is his supposed wife) in Peacock and in the morally perverted psychologist by day, supervillain in a burlap sack by night of the Dark Knight trilogy. He explores the more subtle complexities of human behavior with the self-sacrifice that breaks through the possessive rage of Disco Pigs’s Darren and with the discordant desires for the survival of self and species as a rugged recluse in A Quiet Place Part II. Even as Inception’s boy billionaire, there’s something distinctly sympathetic peering through the thick of his spoiled surface. The titular character of Christopher Nolan’s forthcoming Oppenheimer, then, seems a natural fit, as its real-life counterpart was famously plagued with what his former collaborator, McGeorge Bundy, described as “tragic dimensions in its combination of charm and arrogance, intelligence and blindness, awareness and insensitivity, and perhaps above all daring and fatalism.” On the whole, the actor’s oeuvre is defined by the actual Murphy’s absence from it—the result of an inverted chameleonic capacity for fabricating multiple people with the same face.

Conversely, Geoff Dyer’s persona is distinctly present in everything he writes—even (and maybe especially) when his subject has seemingly nothing to do with him at all. Namely, his book about D.H. Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage, is not so much about Lawrence as it is about Dyer’s struggle to write about him—less an act of self-indulgence than an unself-conscious study of what it is to think and live like the writer. Equal parts critical and comical, Dyer chooses to let his supposed imperfections define his work’s desirability; his inability to be bothered with summarizing, feeding facts, or letting the subject of a story be the subject (or, sometimes, even letting a story take form) is the foundation upon which he built his reputation for genre-bending—most notably in undermining perceived disparities between fact and fiction. But Beautiful, for instance, is not a totally true rendering of its subject; in the semifictional portrait of American jazz, the histories of its luminaries are built out with writing that is as improvisational as its subject. In Dyer’s hands, materiality and the make-believe are indiscernible and, equally, unimportant. In keeping with that legacy, his latest book, The Last Days of Roger Federer, isn’t about tennis, as its title implies and its publishers were led to believe. Instead, it’s about retirement—something his affinity and ability to write about anything suggests Dyer might never achieve—littered with unexpectedly relevant anecdotes from the writer’s own life. The disparity between his books’ proposed subjects and their actual subjects is not a gimmick. Rather, it’s an axiomatic condition of being Geoff Dyer: In writing, he lets the truth of his perspective supersede more technical truths.

Dyer might be a Dark Horse of Literature—at least among his contemporaries. He’s habitually the first to acknowledge those to whom he owes literary debts (Martin Amis, John Berger, Thomas Bernhard, Nietzsche, Milan Kundera, Roland Barthes, to name a few). Nowadays, every writer wants to be a Writer, and every actor an Actor—their success postured as a mere product of their indelible genius. More often than not, this is a semi-transparent myth of their own making. But Dyer and Murphy are all the things that a true Writer and Actor claim to be: obsessive in their (tasteful) influences and not as bothered with fame as they are with craft—altogether refreshing, modern continuations of their professions’ lineages, which, in the last few decades especially, have become widely corrupted as art and celebrity intertwine.

Some years ago, Murphy requested the cinematic rights to Dyer’s Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi—a book marked by really being two books, divided down the middle, without any real transition from a third-person account of the experience of Jeff (not to be confused with, but presumed to be partially derived from Geoff) at the Venice Biennale, to a first-person narrator (assumed to be Jeff) in India’s holy city. For Document, the two meet to define what makes for bad writing, consider how an actor’s value evolves with age, and revisit the possibility of optioning the book.

Geoff Dyer: The extraordinary thing about a film is that you can tell it’s going to be crap in an unbelievably short time—I think 90 seconds is sometimes enough to persuade us the director has no rhythm. Are you able to address this, or does your trade union not allow you to say?

Cillian Murphy: I think you’re probably right. I find it harder to [walk out] at the cinema. It’s an evening out; it’s the investment in the babysitter, in the extraordinarily expensive snacks. I find myself less willing to leave—although, I do.

I have this thing with scripts: If I feel compelled to do something while I’m supposed to be reading it—which is really not that big of an ask, timewise—like make a cup of coffee or cut the grass, I’m out.

In your book, you talk about the difference between walking out of theaters and cinemas, as the etiquette is different. I know, from being onstage, that when someone walks out, the whole fucking place knows it. It’s a massive gesture for both the audience and the performers. Whereas, in a cinema, it’s less controversial. I suppose being in the industry and knowing how much bloody work and bloody money it takes to make anything, I’m more sympathetic to the cause. So, I tend to stick it out a bit longer—[Cuts out]

Geoff: Did Cillian leave?

Cillian: [Reappears] God, I’m so sorry. I’ve had a catastrophic failure of everything.

Geoff: It reflects rather poorly on a man of your stature that you’ve got such a crappy WiFi connection.

Cillian: It’s never let me down like this.

Geoff: It’s funny, it occurred to me that, typically, when a musician wakes up, having taken care of a few biological necessities, they’re really keen to play music. Whereas writing, you get up and think, I’ll have a cup of coffee to get myself going. Then it’s, I think I need another cup. And then it’s, Still don’t feel like writing, because I had too much coffee. It’s only when you force yourself to do it for a while that it becomes this sort of pleasure. I wonder how you respond to that, given your two main forms of occupation.

Cillian: I really don’t play music anymore. I spent an awful lot of time listening to it and going to gigs. Acting isn’t a solo occupation; theater and film and television [are] such massive, chronic, collaborative endeavors that you’re kind of isolated when you’re not working. There are times when you get anxious, but that’s just the nature of it.

I try to convince myself that, when I’m just walking around as a human, that’s research. Raising your family and doing the normal stuff. I never had the urge or the stamina to go from one job to another, because that would be leaving out the research of living everyday life and observing people. You’re kind of like a detective when you’re an actor—or a sociologist.

Geoff, I don’t know if you remember this. It was quite a long time ago. But, um, I tried to get the rights to your book Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi. Do you remember that?

Geoff: I don’t actually remember. I’m not sure I was even aware of it. But feel free to make an offer.

Cillian: It came back from your agent that you said something like, ‘Why would anyone want to make a film of that?’

“I’ve got no interest in stuff that’s entertaining. I’d like to leave the cinema feeling fucked up and winded and punch-drunk, rather than, That was a lovely experience, shall we have a glass of wine?”

Geoff: With regard to optioning my book, my response has always been, you know, Send the check. The great thing for you, the filmmaker, is that I won’t be involved in the process at all. I can offer a complete lack of interference. One of the great joys of writing is that you don’t need anyone’s permission to do it. If you decide, I’m gonna write a big book about the Napoleonic invasion of Russia, you just sit down and do it. I never write proposals for books; I just write them and hope somebody will publish them. Whereas screenwriting, you need permission at every stage. I can’t bear that, it’s so boring.

And I’m just so incapable of any kind of collaboration. There is one kind of collaboration that I think would be my ideal of happiness: I’d be able to play music, and I could meet with people with whom I don’t have any language in common, and we could improvise and jam together. Maybe it’s because I’ve never had any glimpse of that.

Cillian: Well, the times that I did play music in a group, it was truly kind of transportive, because it’s communicating without words. Have you never tried? Because you write so beautifully about music, which is a hard thing to do.

Geoff: I always thought the condition of my writing about music was that I knew nothing about it. Of course, when I was 13, I begged my parents to get me a guitar—which they did. But my dad was so tightfisted, having shelled out for the guitar, he wasn’t gonna pay for lessons. And although some people have a special aptitude for it, I didn’t.

Cillian: I got frustrated, because I plateaued very quickly at playing the guitar. I played the drums, as well, but I knew I was never going to be exceptional. I’ve never gotten any pleasure out of just sitting around, playing other people’s songs; I was keen to write my own stuff. But it became increasingly clear to me, I was just quite average. And I didn’t want to be just average.

Geoff: That point you made about how important it was for you not to be working all the time, because you’ve got to be spending time noticing—I’ve always been struck by the close relationship between writing and acting, in that, to write seriously, you’ve got to be able to notice stuff. With acting, it’s the same thing, especially reading people’s faces. So much acting is in the face, or externalizing emotion by a subtle gesture. I wonder, then, how do you read a script?

Cillian: Oh, gosh. I don’t know. I’ve read a lot since I was a kid—almost exclusively novels. I think your taste in story is formed quite young. I’ve always liked stuff that is a bit provocative, that gets into the knotty, difficult parts of the psyche.

I try not to intellectualize things. I learned early on, it’s not about, This is intellectually challenging or stimulating for me. If something hits me emotionally, I’m in. I’ve got no interest in stuff that’s entertaining. I’d like to leave the cinema feeling fucked up and winded and punch-drunk, rather than, That was a lovely experience, shall we have a glass of wine?

Geoff: I’m aware that if you’re playing a surgeon, you find out about surgery. But I’m really more interested in this thing you call ‘researching.’ I’m imagining you’re just passively going about your life, noticing things on the street constantly, in a disinterested way. Let’s put it like this: You don’t do that because you’re an actor, you became an actor because you were good at doing that.

Cillian: I’m sure it applies to you, too. I’m interested in human behavior and how people live and exist. I’m not interested in a good man’s life, necessarily. I love characters under pressure, what happens to what we consider reasonably normal individuals in quite extreme circumstances. And, of course, we can see that around us all the time.

The biggest thing I learned about acting or observing or being was when I worked with Ken Loach. We made this film called The Wind That Shakes the Barley. Ken’s whole method is that you aren’t given a script; you shoot chronologically, and stuff happens on camera to you as the character. All you have is instinct. It was revelatory to me. I still do the research and read all the books and talk to all the people and learn how to ride the fucking horse or drive the car or shoot whatever. But when I get on set, I abandon it all. It’s about being in the moment, and trying to be truthful.

Geoff: I’ve been aware, when I’ve gone to a place to write about it, of how tiring it is—noticing. At one point, my wife said to me, ‘I don’t know how you do it.’ I was thinking, Oh, this is great. I’m gonna get a nice compliment here. She said, ‘You’re just oblivious to the world. You’re also incapable of making anything up.’ And it was sort of true, actually. One of the reasons I’ve ended up writing the kinds of books I do is [that] I don’t have enough attentiveness to the world to be a fully formed, fully functioning novelist.

“I still do the research and read all the books and talk to all the people and learn how to ride the fucking horse or drive the car or shoot whatever. But when I get on set, I abandon it all.”

Cillian: In your book But Beautiful—which I adore; I’m a jazz fan, but not as much of an aficionado as you are—the detail was extraordinary. All those players, how you got inside their heads. That, to me, is all about observation, even though you were making a lot of those situations up, I presume?

Geoff: What I’ve become really aware of recently is this question of my particular consciousness. Quite a lot of nonfiction, it seems to me, could be written by anybody, if they have a certain expertise. Whereas, for the kind of nonfiction books that I’m doing, there’s a subject that I’m addressing—but the crucial thing is the saturation of that subject with my consciousness. And that is apparent both at a very, very small level, in terms of observations, and also, it’s vast—it’s my take on the world.

Style, as I think we’d agree, is not just some varnish or glaze that you put on as a form of enhancement at the end. It’s really your perception of the world; it’s got that kind of phenomenological dimension to it. I’ve been on this Anita Brookner binge recently. Am I interested in the lives of these lonely spinsters, living in mansion blocks in London? Not particularly. But it’s the way that every book is so completely saturated, from the smallest word choice to the biggest apprehension of the human spirit in a particular circumstance.

Cillian: [When] did that path, in terms of the sort of writing you do, click?

Geoff: When I was 18, socially, my experience was limited to drinking beer in pubs. Although I couldn’t manifest it, my actual understanding of the world, of gesture and psychology, was much greater than it might have appeared for a very simple reason: I’d read Middlemarch. When I left university, the crucial thing was my discovery of the work of John Berger, who had pioneered this form of writing which was both creative and critical; it was a form of commentary, and it was also imaginative. That made available for me this space between being a novelist and being a critic. I didn’t want to just be a critic, but I was always hampered as a novelist by not really being able to think of stories so much—I suspect Cillian has frozen again…

[Cillian reappears] It seems you always freeze when I’m going on too much.

Cillian: You just got to Berger there, and then my fucking thing did something.

Geoff: Because Berger’s consciousness is so strong, it took me a while to emerge out of that, and gradually come into my own. It took me a while to realize how important it was for me to be funny all the time, as well.

Cillian: I remember reading a quote by Kazuo Ishiguro on this thing called an art blender. In the art blender that’s turned up high, you don’t really see what’s in there; and in the art blender that’s turned on low, you can kind of see the ingredients in it. For me, as an actor—and certainly as a younger actor—I’ve liked the more transformative stuff, where the blender is turned up really, really high. I’ve done it a bit, where you play a character that is very few degrees away from yourself, and I find that more challenging. I’m interested in trying to disappear a lot of the time. I don’t know where that comes from. I’ve not really analyzed it.

Geoff: This book of mine [The Last Days of Roger Federer] is about last things, and I think this may even be one of the last things we talk about: Acting, a lot of it is about the face. And part of what’s going to happen to you in your career is going to be tied up with your face, isn’t it? I’m gonna put this in a rather stupid way: How invested are you in your face?

Cillian: The disadvantage, I suppose, of being an actor is that you are confronted with your aging process all the fucking time. But that’s just the nature of it. And you have to make peace with that.

Geoff: David Thomson, in his brilliant [The New] Biographical Dictionary of Film, is so good about the way that, sometimes, actors achieve a greater depth as they age, because of the changing of the face, and the experience that goes into it. [It’s] similar to when you listen to the late quartets of Beethoven; you’re hearing everything that he’s experienced in his life. They’re so deeply personal, but also vastly cosmic.

Cillian: I was fascinated by your book, because I’m always thinking about retiring. When is it the gracious time to bow out? I think one of the most irrelevant things you can do is try and remain relevant. It’s easier for a writer, I think—because, as you said, you can decide the agenda. Whereas, as actors, you need to be in something. I try not to think about it. But actors are, by nature, vain and insecure creatures. It’s just trying to keep it balanced so that you’re not a terrible person to be around.

Geoff: Cillian, I really don’t want you to think I’m a terrible hustler, but can I give you my email address?

As soon as I said that, it looked like you froze again. But if you were serious about Death in Varanasi, we just turned down an offer the other day.

Cillian: I think it will be a stunning film—because it’s two films, effectively. When I read it, I imagined that that cut down the middle would be such a bold, brave cut.

Geoff: Well, let me give you my email address, now. We can get it in the chat.

Cillian: I don’t know how to… How do I save that? Let me find a pen.

Geoff: It’s great that I’m more technologically advanced than somebody on a call. It’s not happened before.

Cillian: Technology seems to have issues with me. Everywhere I go, things break down and go wonky.

Geoff: Well, Cillian, as we’re always hearing these days, you’ve got to take responsibility for your actions.

Cillian: Indeed.

Groomer Gareth Bromell at Walter Schupfer. Set Design Grainne Walsh at Grey Area. Photo Assistants Rory Cole, Darren Moriarty, Jake Hoffman. Stylist Assistant Katie-Ruby McLaughlin Robinson. Tailor Cleo Prickett. Production Not Another Intl. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan. Talent Director Tom Macklin. Retouching Andy at Love Retouch. Scanning Touch Digital. Oppenheimer releases globally July 21.

Document Journal Spring/Summer 2023 Issue No. 22 is available for pre-order now. New covers will be unveiled over the coming days.