In banning renderings of Chinese president Xi Jinping worldwide, Midjourney sparked debate about the policing of AI-generated content—and the line between regulation and censorship

With the AI image generator Midjourney, you can make satirical images of Joe Biden, Vladimir Putin, the Pope, and other world leaders—but Chinese president Xi Jinping, one of the most powerful government officials in the world, cannot be mocked.

If you think this is odd, that’s because it is—because, while China’s restrictions on free speech should theoretically only apply within its borders, Midjourney’s CEO wants his program to be available in the nation. So, to demonstrate his compliance with its censorship policies and ensure his app’s continued viability, he’s decided to apply them to users in free countries, too. As Sarah McLaughlin, an advocate against global censorship, writes, “Here we have an authoritarian country’s censorship laws setting the moderation standards for the global community in an emerging tech field”—and this, she says, sets a dangerous precedent around the censorship of AI products.

Under China’s authoritarian regime, chatbots are subject to the same rigorous censorship as web searches—and, as a result, Chinese chatbots are programmed to dodge questions about politics. According to experts in the field, efforts to develop bots that can reliably evade potential landmines are likely to be a major barrier in the progression of Chinese chatbot technology—because, while it’s possible to predict a majority of chatbots’ responses to user queries, they are famously prone to going off the rails, or being tricked into breaking their own rules. This means that, ironically, Xi Jinping’s aspirations to compete with the US in the development of such technology are fated to clash with his own censorship regime—and, as Nicholas Welch puts it, “A chatbot that produces racist content or threatens to stalk a user makes for an embarrassing story in the United States; a chatbot that implies Taiwan is an independent country or says Tiananmen Square was a massacre can bring down the wrath of the CCP on its parent company.”

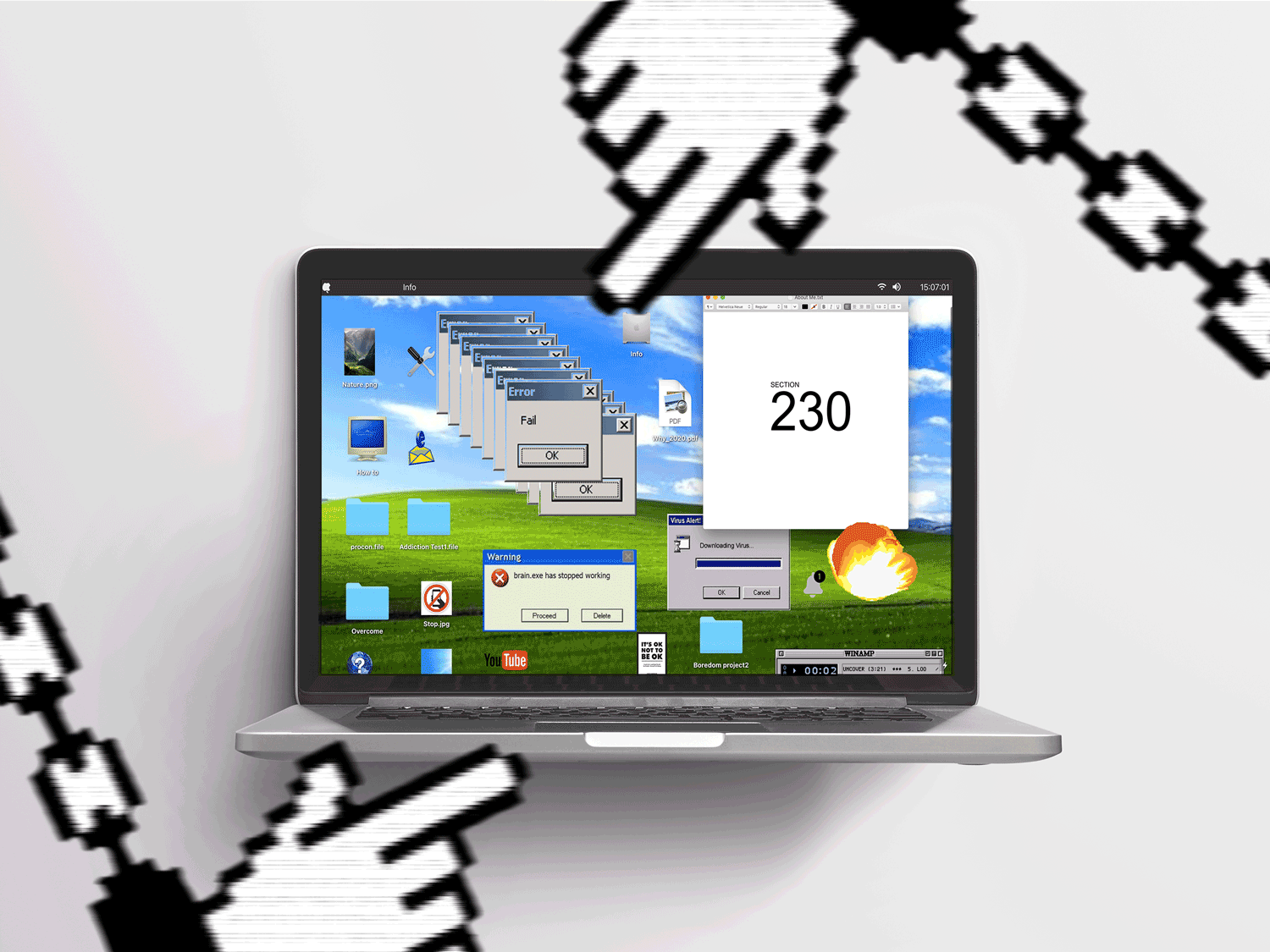

Efforts to regulate the output of chatbots are likely to pose significant challenges in the US, too. According to lawyer Matt Perault, the emergence of generative artificial intelligence will usher in a new era in the platform liability wars—because Section 230, the law that shields online platforms from being held accountable for user-generated content, likely won’t apply to language models. The law doesn’t distinguish between image and text, but it does differentiate between hosts and content creators—and because machine learning models like the now-viral ChatGPT, and popular image generators like Midjourney, are actually generating content, they’re liable to be held accountable in ways that previous digital communication platforms were not.

“The emergence of generative artificial intelligence will usher in a new era in the platform liability wars—because Section 230, the law that shields online platforms from being held accountable for user-generated content, likely won’t apply to language models.”

But just because we can hold LLMs accountable, doesn’t mean we should. The issue with holding platforms accountable is that problematic content inevitably slips through the cracks of content moderation systems—and while it may seem like these laws would siphon power away from big tech, chipping away at liability protections actually increases the risk for smaller platforms and websites that can’t afford to defend themselves from a potential lawsuit.

As evidenced by previous efforts to amend Section 230, a law’s intention is not necessarily its effect: FOSTA-SESTA, the 2018 legislation that was supposed to hold companies accountable for enabling child traffickers, actually resulted in the widespread banning of all sexual content online—which, in turn, made sex traffickers harder to find. It also had a catastrophic impact on the safety and well-being of sex workers, many of whom lost access to vital resources like the ability to advertise their services or vet clients online. “We are continuing to see moral panics being stoked to pass legislation to ‘save the children’ and ‘stop sex trafficking,’ without meaningful analysis of how these bills actually do nothing to protect vulnerable communities,” sex worker and activist Danielle Blunt told Document, asserting that these laws do little to address the actual issue at hand: the moralization and policing of content, whether sexual or political.

Perault agrees: “As a law, FOSTA-SESTA didn’t work. But unfortunately, there’s no legal mechanism to say, We screwed up, we got that totally wrong.” That’s why he’s advocating for a more experimental approach to the regulation of LLMs, stating that, because the societal impact and problematic use cases of new technologies are hard to predict at the outset, it’s important not to pass any overarching (or overbearing) regulations early on. “The expectation shouldn’t be that we get it perfect on day one,” Perault says. “Rather, we should leave room for experimentation, closely track impact, and look at how the legal regime is working in practice—otherwise, we’re going to have another problematic law on the books for decades.”

And, in the meantime, you can still make AI-generated pictures of the Pope.