Curator Leonardo Bigazzi joins Document to expand upon the film’s collection—reflecting upon the experience of art through the screen and the ways in which it constructs its own narrative

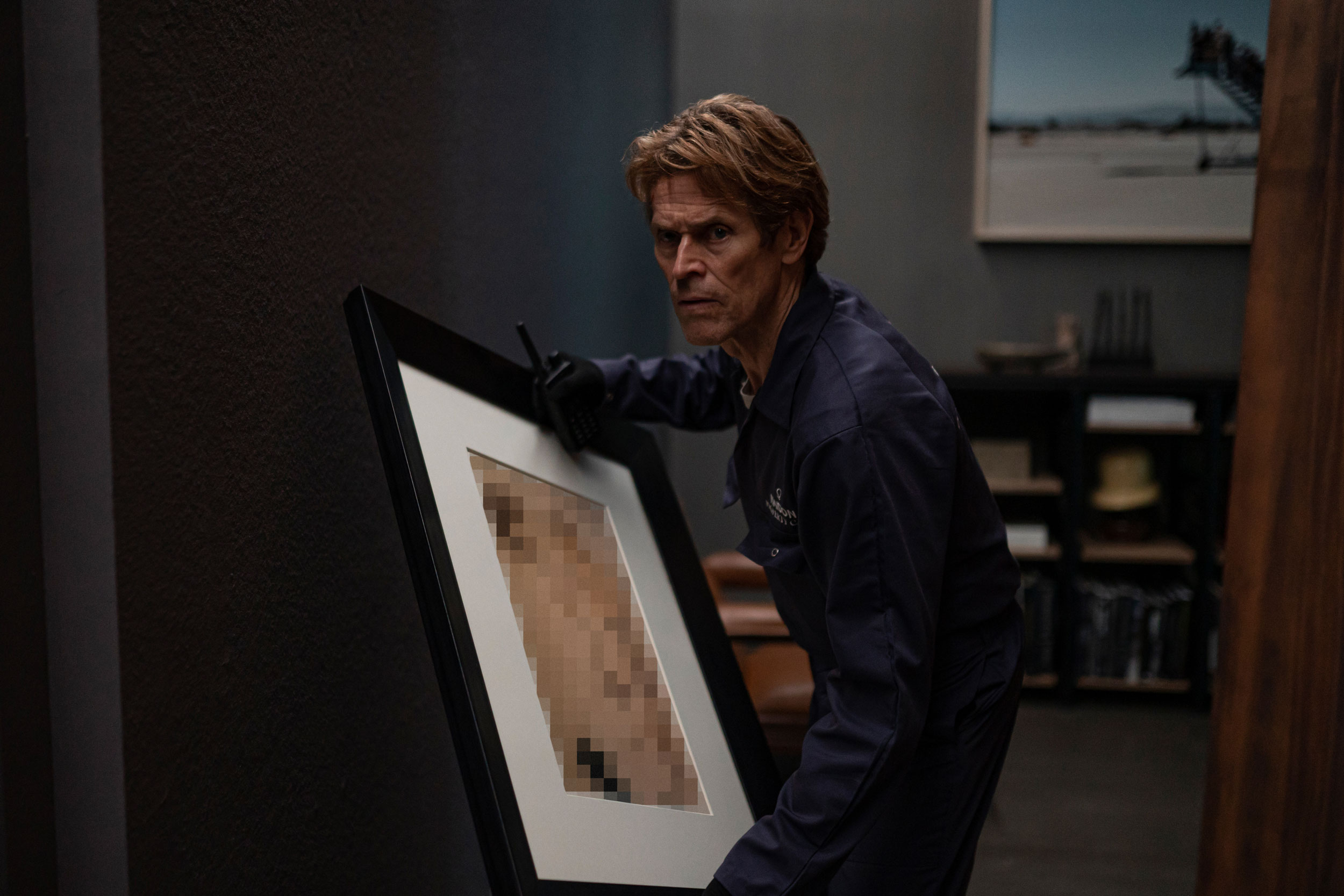

Willem Dafoe is a sculpture—and not just in the character-actor type of way, that lets him shape himself into someone new. It’s also in the mere form of his face, its angular composition and its capacity to elicit emotion with only a stare. In Vasilis Katsoupis’s Inside, Dafoe is the subject of a strange installation. The film follows his character, Nemo, an art thief, to an ultra-upscale apartment in New York. He and his faceless accomplice (whose role over the radio is short-lived) are plotting to steal a $3 million self-portrait of Egon Schiele when the security system is corrupted, and Nemo is left stranded in the brutalist luxury home with only an aquarium fish and the art on the walls to keep him company.

Aside from passing appearances, in hallucinations or real-time security footage of the lobby downstairs, Nemo is Inside’s sole character—or, rather, its sole character that’s granted physical form. Though we never meet him, the apartment’s owner is arguably further built out than Nemo himself. He’s introduced early on as a Pritzker Prize-winning architect; his person is built not from the performance of an actor, but from the sterility of his apartment’s decor, the immensity of wealth he displays, and, perhaps most expressly, the art in his collection.

Each painting, sculpture, and installation is an insight into the architect’s personhood. The seductive works that hang in his bedroom hint at his bachelor status, the video installations that dominate large rooms imply a need to entertain, and works from both modern masters and those who have only recently achieved international recognition reveal a breadth in taste, suggesting a real knowledge of the pieces as art rather than mere financial investments.

Ahead of Inside’s release, its curator Leonardo Bigazzi joins Document to expand upon the film’s collection—reflecting on the experience of art through the screen and the ways in which it constructs its own narrative.

Megan Hullander: I am curious as to how you went about establishing the character of the collector, without a physical person.

Leonardo Bigazzi: The collector needed to be somehow sophisticated. He’s not buying work as a finance broker from Wall Street as an investment. He knows what he’s buying, and why he’s buying it. That’s why some works have this kind of minimalistic and abstract style, and others have a very strong political statement embedded into them. He’s able to mix masterworks with more abstract, contemporary work.

At the same time, the collector had to come across as someone who likes to show wealth, who likes to have parties [amid] his art collection, who likes to be portrayed in a masculine way. Because there is part of you that, throughout the film, needs to be happy that [Nemo] is attacking the apartment. An art collection is an extension of the person who put it together.

Megan: How does the art establish a sense of narrative that’s maybe congruent with the script, but not entirely matched to it?

Leonardo: Vasilis [Katsoupis] had some ideas, of course, that I followed and gave form to. Some of the works were responses to moments in the script, and others were works that shaped the script.

For example, in the scene when [Nemo] takes the photograph [of the Maurizio Cattelan] where the gallerist is strapped to a wall, pushes it down, and says, ‘I feel you brother, I’m going to set you free’—that was not in the script, it came as out of the art. He felt, This guy’s been looking at me for days, I want to get him out of that wall. I’m trapped here, but I can set him free.

Petrit Halilaj developed work for the Venice Biennale in 2017, and he decided to create a piece for us. When I was walking Willem through the space, he said, ‘Maybe I could wear that. Would that not be something that I would try to wear, that could keep me warm?’ And so that became part of the script. I think because the film was shot chronologically, Willem [was able to] make his own relationship with the artworks, and generated new possibilities from them.

“The relationship that the audience will have with the artwork is mediated by a screen. I’m really fascinated by what art is able to activate when it sits in a context where you don’t expect to find those questions.”

Megan: How did knowing that the pieces would be experienced on-screen, rather than in-person, inform your selection?

Leonardo: I work for a foundation [called] Fondazione In Between Art Film in Rome, which was established by Patricia Bolgheri as a way to support visual artists who work between cinema and art. Working on the boundaries of different mediums—that’s the space where real transformation happens. For example, the possibility to reach new audiences.

When I was invited to this project, I immediately thought about the incredible cross-generative possibilities that commissioning works for a film could generate. Like you said, the relationship that the audience will have with the artwork is mediated by a screen. I’m really fascinated by what art is able to activate when it sits in a context where you don’t expect to find those questions—because art is about raising questions. So some of the words are very strongly politically-charged. Some talk about migration, some talk about queerness or gender. So what happens when these images, which almost [function] as a subliminal subtext, enter the visual repertoire of the audience of the film? I hope that Inside will reach a vast audience that ranges from art connoisseurs to people who are just watching because they are Willem’s fans.

Megan: How do you think the film might be a different experience for someone who is well-versed in art, compared to the general public? And how do you work to ensure that even someone without that kind of knowledge would understand what the art was hinting at?

Leonardo: So with the work of Adrian Paci, titled Centro di permanenza temporanea, you see people stuck on a plane that’s not there. If you see this image, which is recurrent in the film—Willem even cries looking at it—even if you don’t know anything about it, there’s the idea of being suspended in a sort of a limbo where you don’t know where you’re going. It’s a surreal image. Paci’s an Albanian immigrant who [came] to Italy in the ’90s. And many of his friends were kept in these centers for immigrants before they were allowed—if they were allowed—to enter the country. And when you’re there, it could be for one year, it could be for two years, it could be for three months.

It’s the same as the Maurizio Cattelan, [where] you have a man attached with duct tape to the wall. Obviously, this is an image—even if you don’t know anything about it—where you know he is trapped and not able to move. In ’99, when Cattelan was invited to do the first show at the Massimo De Carlo Gallery, instead of putting his paintings on the wall, he put his gallerist on the wall. He was attached for eight hours, and actually passed out and had to be towed away in an ambulance. And so, if you know this, the moment when he says, ‘I’m going to set you free’—it’s fantastic.

“Art always finds its way. I have huge trust in the fact that, even in the most neutral settings, those questions find their way through.”

Megan: You’ve spoken a bit about how art plays into the narrative function, but were there any specific works that you felt really explored the more general messaging behind the film, which questions the value of art itself?

Leonardo: Selecting some works that are very politically charged activates questions that are related to what you just mentioned. Like that work by Paci: What happens when it leaves the gallery or a museum, and it enters the house of a wealthy collector in New York? Are we sure that collectors fully understand the scope of that work? Probably not. I know collectors who are incredibly knowledgeable, who are more prepared from an art history perspective than many curators I know. And I know collectors who only buy because the advisor tells them that this is going to be the thing that you’ll put on auction in 15 years.

But what I like is that art always finds its way. I have huge trust in the fact that, even in the most neutral settings, those questions find their way through. I think the works we selected activate this idea of what remains, apart from the physical existence of the work.

Megan: How did you go about selecting the artists who you thought would be suited to make work that would fit within this film? And given the unusual setting—a non-gallery or museum space—how did you convince these artists that it was worth participating, or that it added value to the piece itself?

Leonardo: Six works were commissioned and 19 were selected—replicated for the film or lent from the studio of the artists. There was a constant dialogue with the artists and estates on what their work was bringing to the film. I think that was the only way that the artists would generously give a work that would then serve the purpose of contributing to the vision and the creativity of someone else. Artists are not used to this; when they show in a gallery, it’s their statement, not the statement of someone else. In this case, it serves the purpose of the narrative—the creative vision of someone else.

Some of them, I think, will become greater artworks because they are in the film. The Petrit Halilah, again, for example, is a costume that Willem uses in his performance, and if a stain happens, it becomes part of the history of the piece. You have work being commissioned for the film, which becomes, conceptually, part of the work.