The 27-year-old Malian-Canadian is among New York’s youngest curators—and her namesake gallery is dedicated to bringing marginalized artists to the fore

“My preschool report card said I wanted to be a mother, a Spice Girl, and a teacher—in that order,” says Hannah Traore with a laugh. Against all odds, the 27-year-old Malian-Canadian ended up becoming one of New York’s youngest gallerists and a Forbes 30 Under 30 nominee before achieving any of the benchmarks set by her younger self. Looking back, she wouldn’t have it any other way.

Traore’s namesake gallery is the culmination of a lifetime of experience with art. Raised in a creative household, she was taught to embrace individuality of all kinds—a philosophy she now carries forward in her curatorial work. The artists represented by the gallery are all of color, Indigenous, queer, or otherwise underrepresented in the contemporary art world. But while they happen to be from these groups, Traore emphasizes that she’s choosing them because the quality of their work speaks for itself. “Often, artists are forced to talk about that identity, with institutions being like, ‘We want an Indigenous artist’s work to look Indigenous. We want a Black artist’s work to show a Black face. We want queer artists to make work about being queer.’ So even if it’s abstract work, people are gonna say, Where’s the queer in that? Where’s the Black in that?” she says, explaining that her gallery aims to offer an alternative to this common approach. “Artists should be able to choose whether they want to speak overtly about their identity—because your identity is always in your work, but it doesn’t have to be the focus.” Traore is, in other words, affording minority artists the privilege that has always been extended to the majority.

Part of the reason Traore started her own gallery is that, having worked within high-profile, predominantly white institutions like MoMA and Fotografiska, she’s witnessed firsthand the way old-school thinking pervades even their efforts to diversify. “I was really tired of working for big institutions that just didn’t care about my opinion,” she says, explaining that while efforts and improvements are being made, people like her—staffers at the bottom of the food chain—weren’t being listened to by the old guard. “I always thought that if I opened my own gallery, it wouldn’t be until later in life,” she explains—but when she found herself laid off and living at home at the height of COVID, she began considering other options. “I don’t think there’s ever going to be a perfect time, because you’re never going to feel ready to do something like that. But over the pandemic, I had time to think, and really develop the business idea to the point of actually being viable—and I realized that I had a strong vision and value proposition, so why not do it now?”

It’s an experience Traore shares with countless other white collar workers who, having been laid off during the pandemic, were made aware of their relative powerlessness within large institutions and companies—and, while at home or on unemployment, finally had the opportunity to consider investing in their own businesses. According to the US Census Bureau, 24 percent more aspiring entrepreneurs filed paperwork to start businesses in 2020 than in the year prior, resulting in 4.4 million new business applications—a record high. Traore emphasizes that she’s privileged to have spent the pandemic living at home, rent-free, with a family who encouraged her to pursue her passions. She describes a childhood spent making arts and crafts at home, from tie-dyed t-shirts to papier-mâché. “My mom would always joke that she’d be hurt if one of her kids became an accountant. And it’s funny—but also like, I think that’s true,” she laughs.

Traore possesses an infectious enthusiasm that, combined with her quick wit and business savvy, is hard to say no to—but she maintains that, given her rapid transition from curatorial intern to the founding director of her own gallery, she’s as surprised as anyone else to find herself in a position of power and influence. “It’s not that I wanted to open Hannah Traore Gallery just for the sake of it. It’s more that my ideas were different than what I was encountering in the contemporary art world, and I felt there was a gap that could be filled,” she explains. She almost didn’t include her own name in the title, but ended up deciding that it was important for public perception that the gallery have a female, West African name. “I know how much it meant to me to have a Black boss for the first time,” she says. “I wanted to be that for my artists: a gallery that makes them feel seen and understood in a way that maybe other galleries wouldn’t be able to. My hope is that having the name Traore, which is one of the most common surnames in Mali, will make it feel accessible to those who see it on the street and recognize it.”

Elitism is all but synonymous with the contemporary art world, but Hannah Traore’s inviting Lower East Side space encourages visitors to check their pretensions at the door. The idea of being accessible to the public is embedded even in the gallery’s interior design, which incorporates soft curves to counteract the sharp corners and “white cube” feeling common in conventional galleries. Drawn to the possibility that foot traffic might attract those outside of the art world, Traore aims to make it a place where anyone can comfortably enter and appreciate the work inside. She is also interested in expanding notions of how galleries can engage with their surrounding communities, and is currently working on a project in collaboration with three local schools in the neighborhood. “I’m doing a beautiful show and an opening for them, making them feel special, and then getting all the money back to them,” she enthuses.

Traore attributes her focus on community engagement—and the fact that she entered this industry at all—to the pioneering Black creatives and businesswomen that came before her, from documentary filmmaker and nonprofit executive Linda Goode Bryant to contemporaries like Nicola Vassell. She also recognizes the contributions of her longtime mentor Isolde Brielmaier, an entrepreneurial and curatorial powerhouse whose advice has proved invaluable in navigating the historically white art world.

Born to Jewish and Muslim parents, Traore’s own experience of multiple cultures was formative to her worldview, and made her very empathetic toward “anyone who can relate to the experience of otherness,” she says. Growing up in the melting pot of Toronto—among the world’s most multicultural cities—she soon gained a reputation for confronting anyone who said something homophobic or racist. “In the fifth grade, we had to write a paper and give a speech on anything we wanted,” Traore says, recalling an early manifestation of these values. “I’ll never forget it: Another girl in my class did it on tree frogs. What did I do it on? Gay rights.”

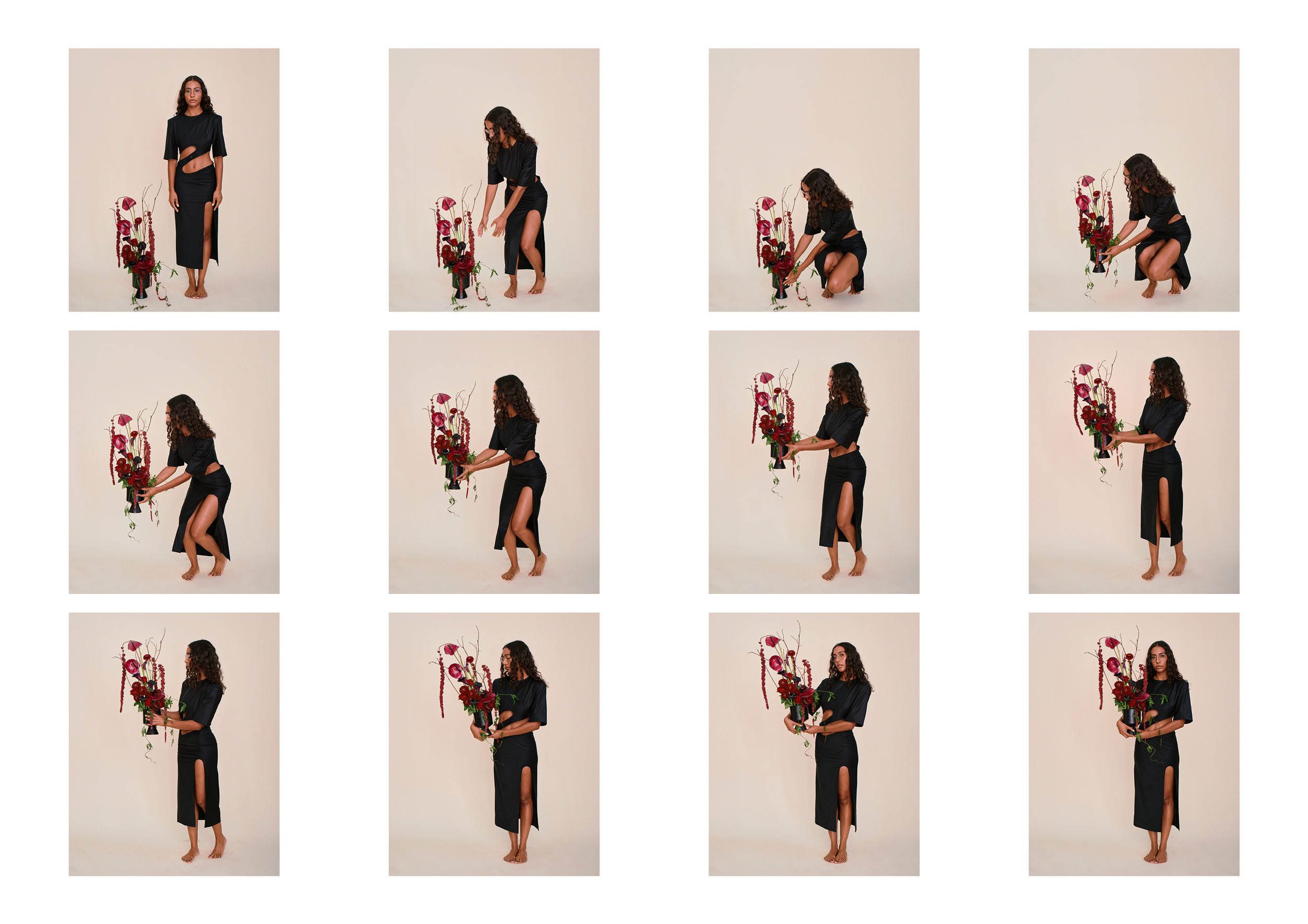

As a young business owner, Traore considers herself tremendously lucky to be able to work toward a goal that’s aligned with her values. And work hard, she does: During our conversation, she is simultaneously present and engaged with me, and manning the ship back at the gallery—calling Ubers for her gallery manager, or pausing to send a brief voice note about construction, for which she apologizes effusively. Running a business has been a learning curve: “I always say it’s a blessing and a curse that I never worked in a gallery before this,” she says, explaining that, while there are certain systems she’s had to devise on her own, she also never had to unlearn the unspoken rules internalized by so many in the contemporary art world. As a result, her approach to curation is unlimited by conventional assumptions about the value of “fine art,” embracing collaboration across design and fashion to broaden the notion of what belongs in a gallery setting. The same is true for the curatorial selection process: Whether internationally recognized or all-but-unknown, the artists she works with define themselves by the quality of their contributions. “For example, one of my artists, Camila Falquez, had never done anything in the fine arts world—her work had just never been seen that way,” Traore says. Her first solo exhibition, Gods That Walk Among Us, was held at the gallery earlier this year, and saw the artist channeling the conventions of surrealism to address narratives of community and humanity—pushing back on preconceived notions of gender, power, and beauty in vibrant, emotive portraits by honoring a contemporary spectrum of social and gender diversity.

For Traore, artists and their visions are always front of mind. Her mission is to provide a platform for them to create the works they haven’t yet been given permission to. Today, Hannah Traore will celebrate its one-year anniversary—a fact she finds shocking and exciting. “To hear from my artists, and from the community, that they feel like it’s the first time they felt comfortable in a gallery—that means the world to me,” she says. “That’s how I measure success.”

Hair by Daniel Lutz. Makeup by Tanya Marques.