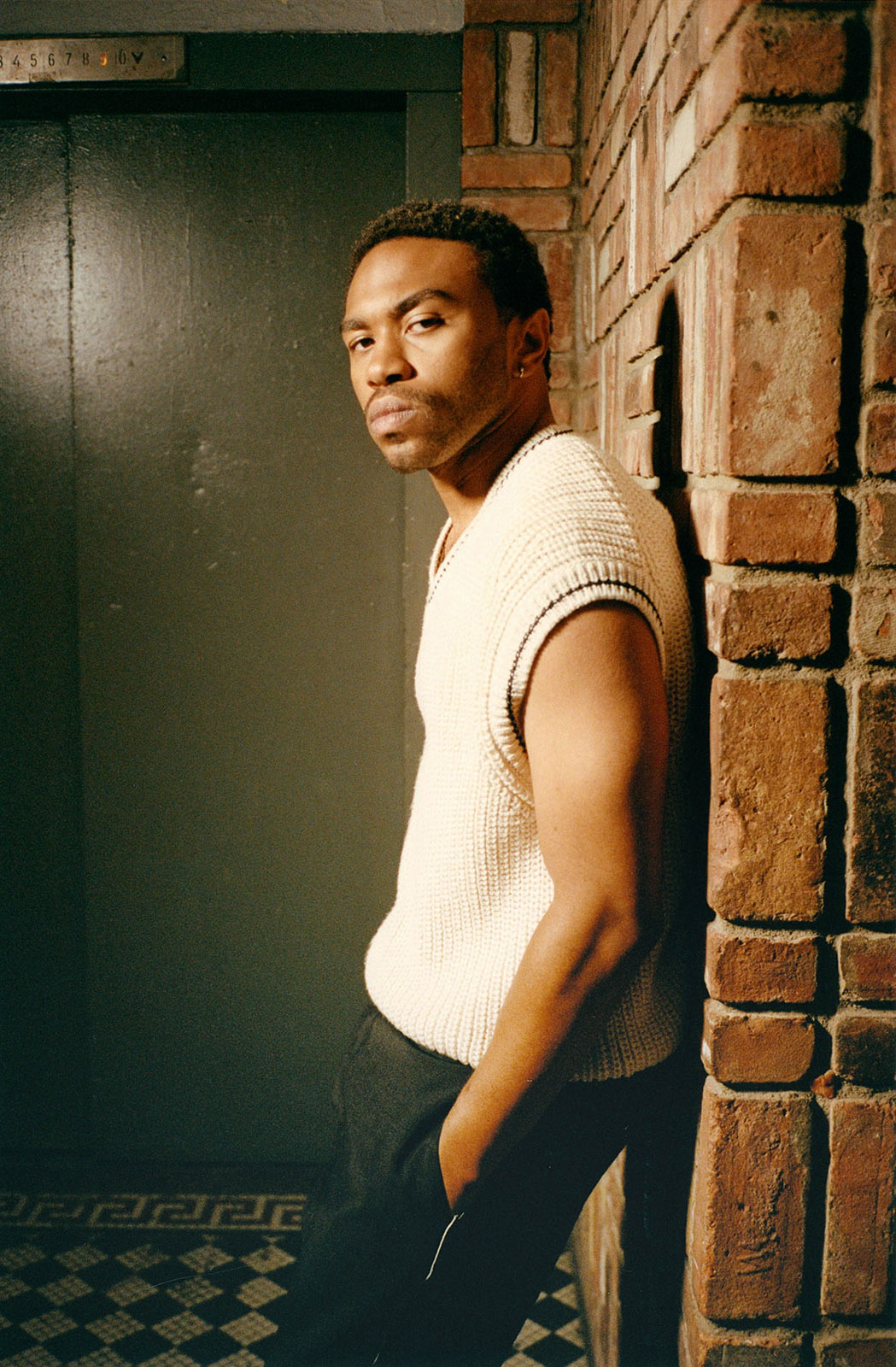

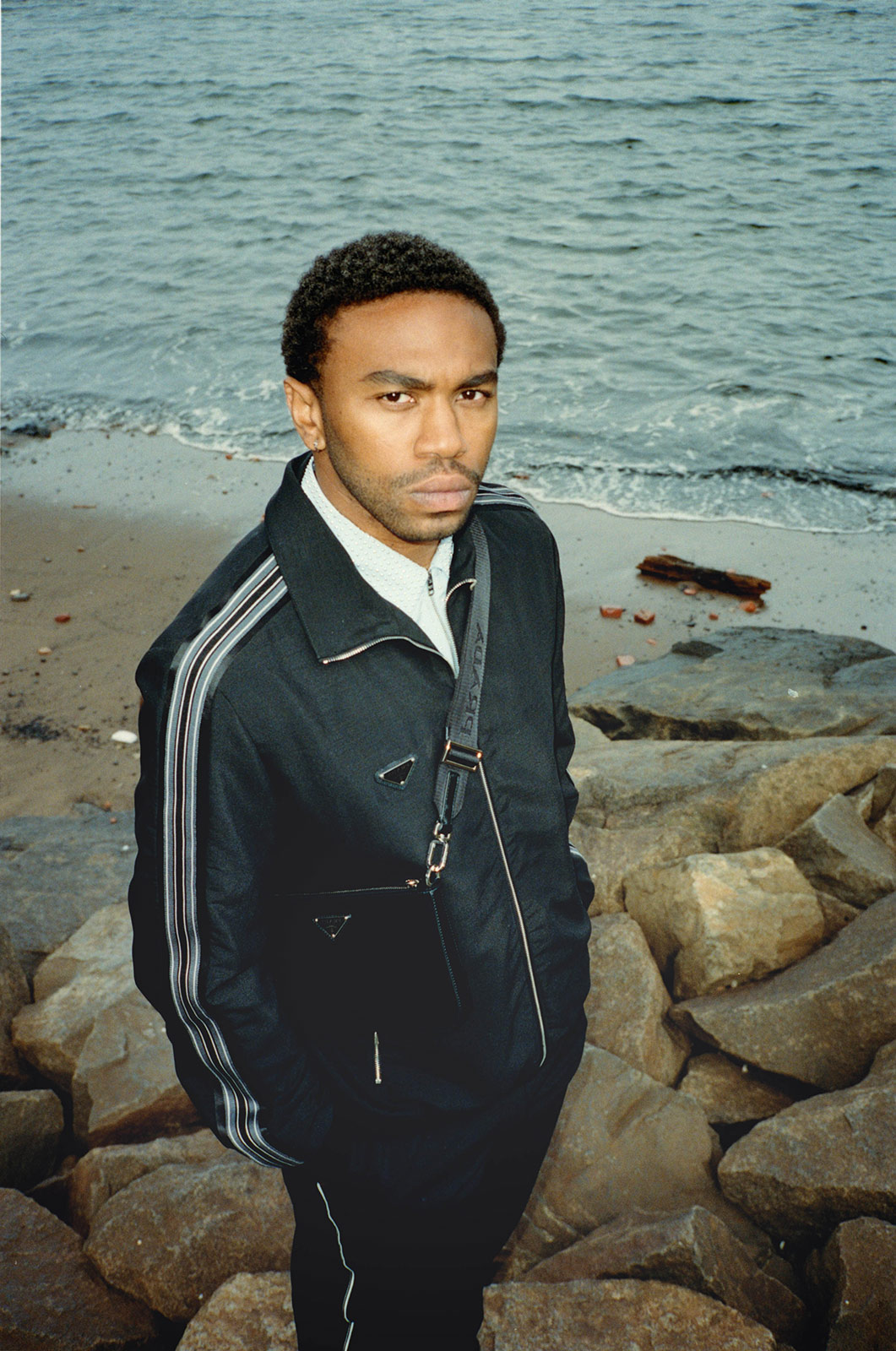

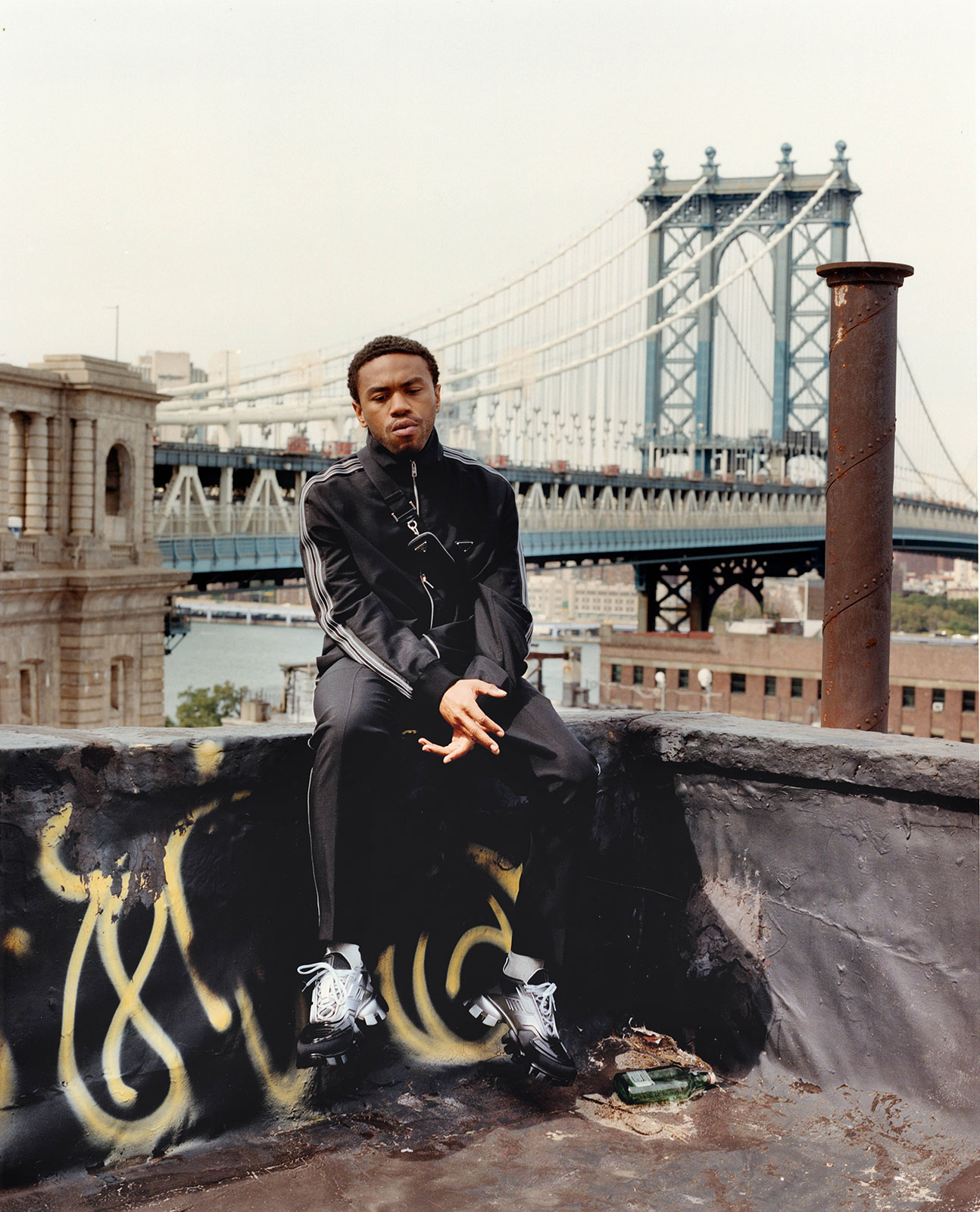

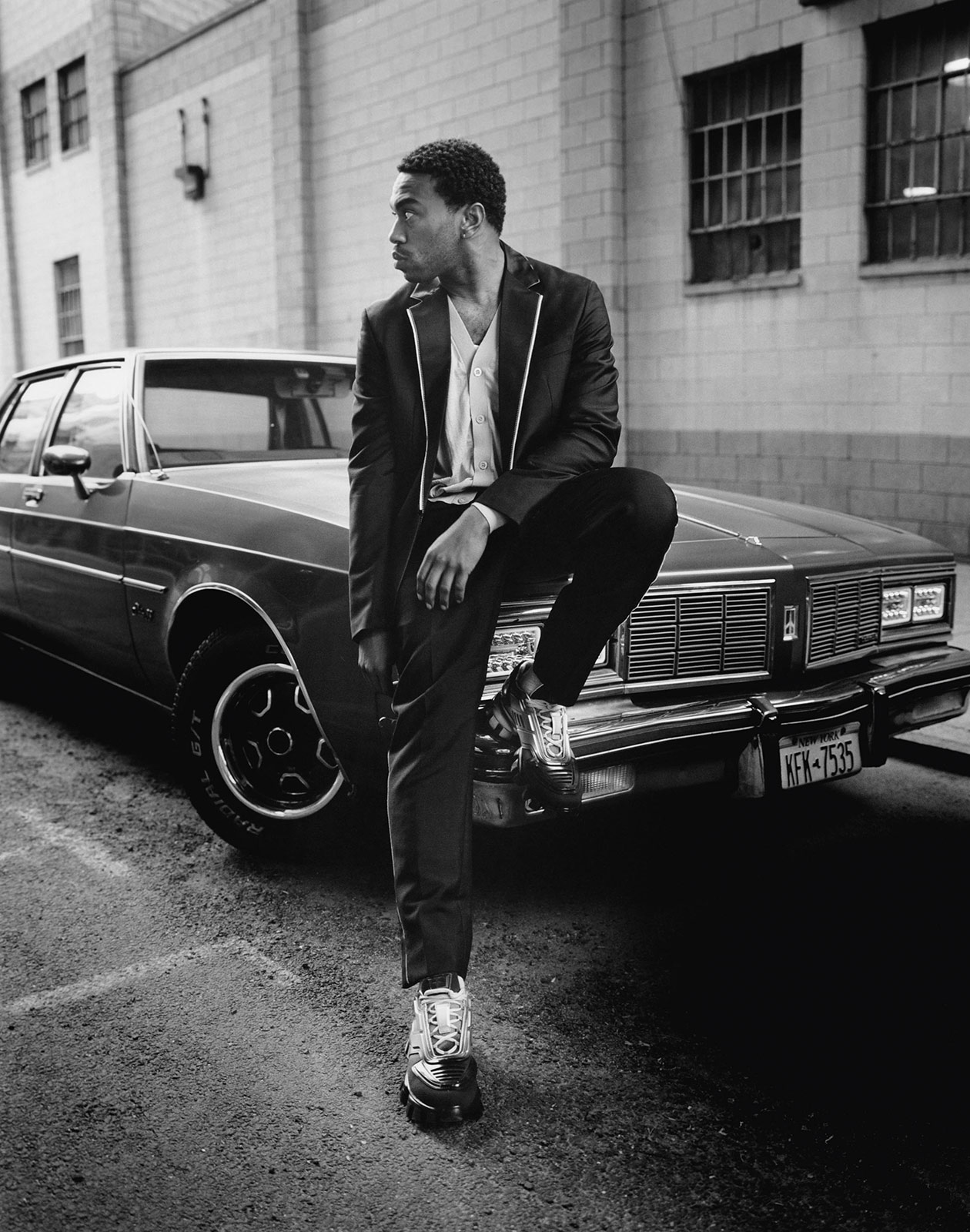

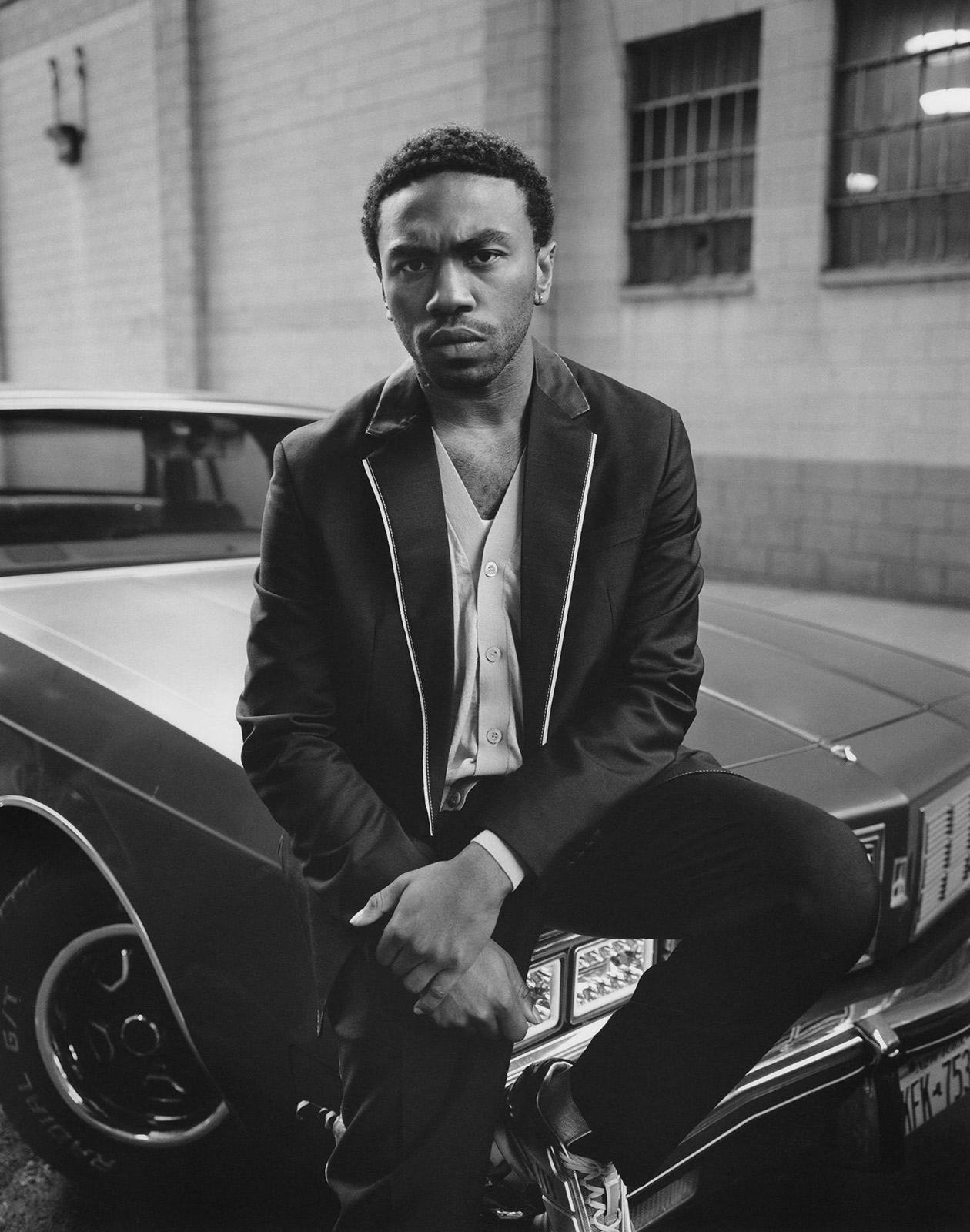

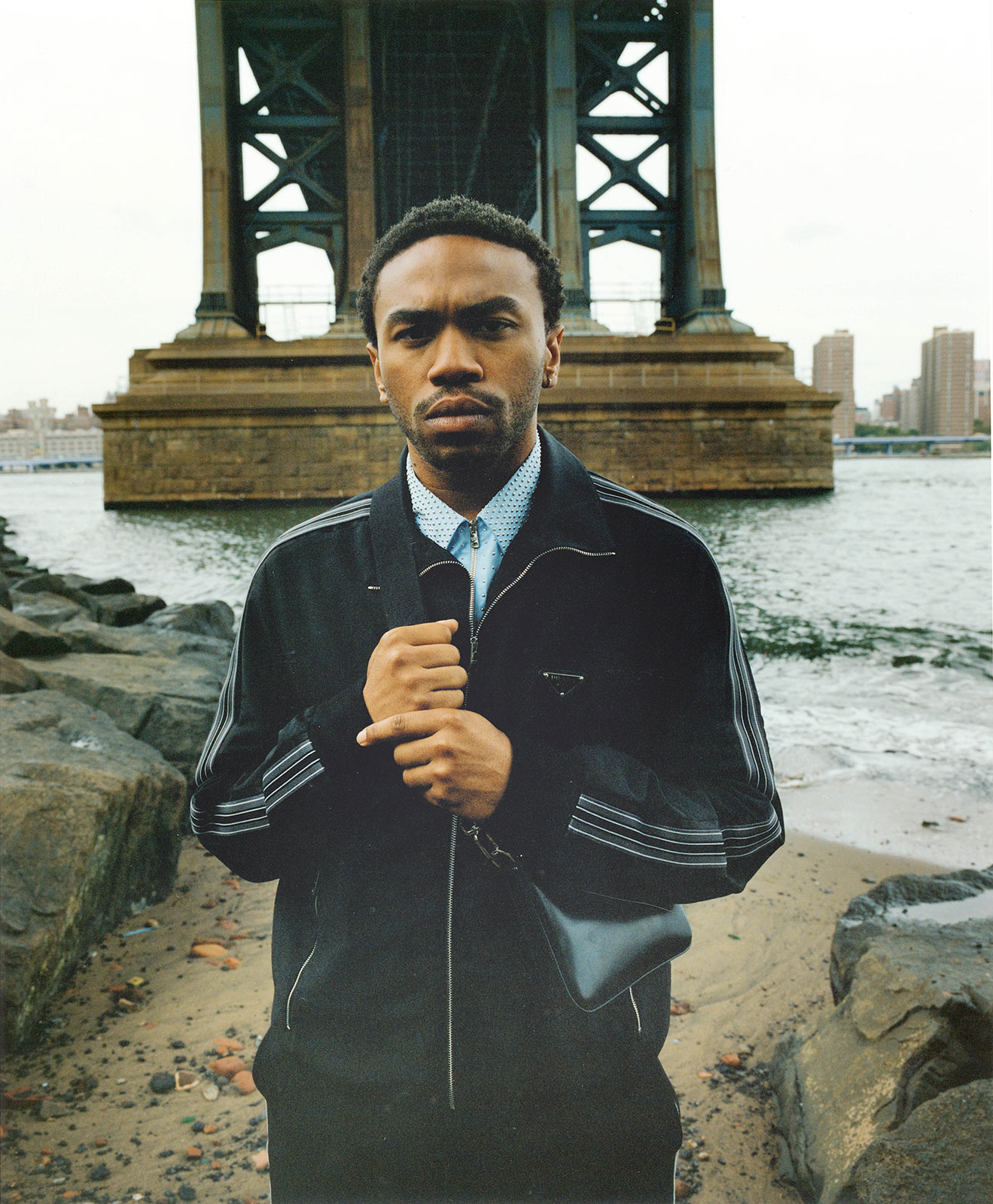

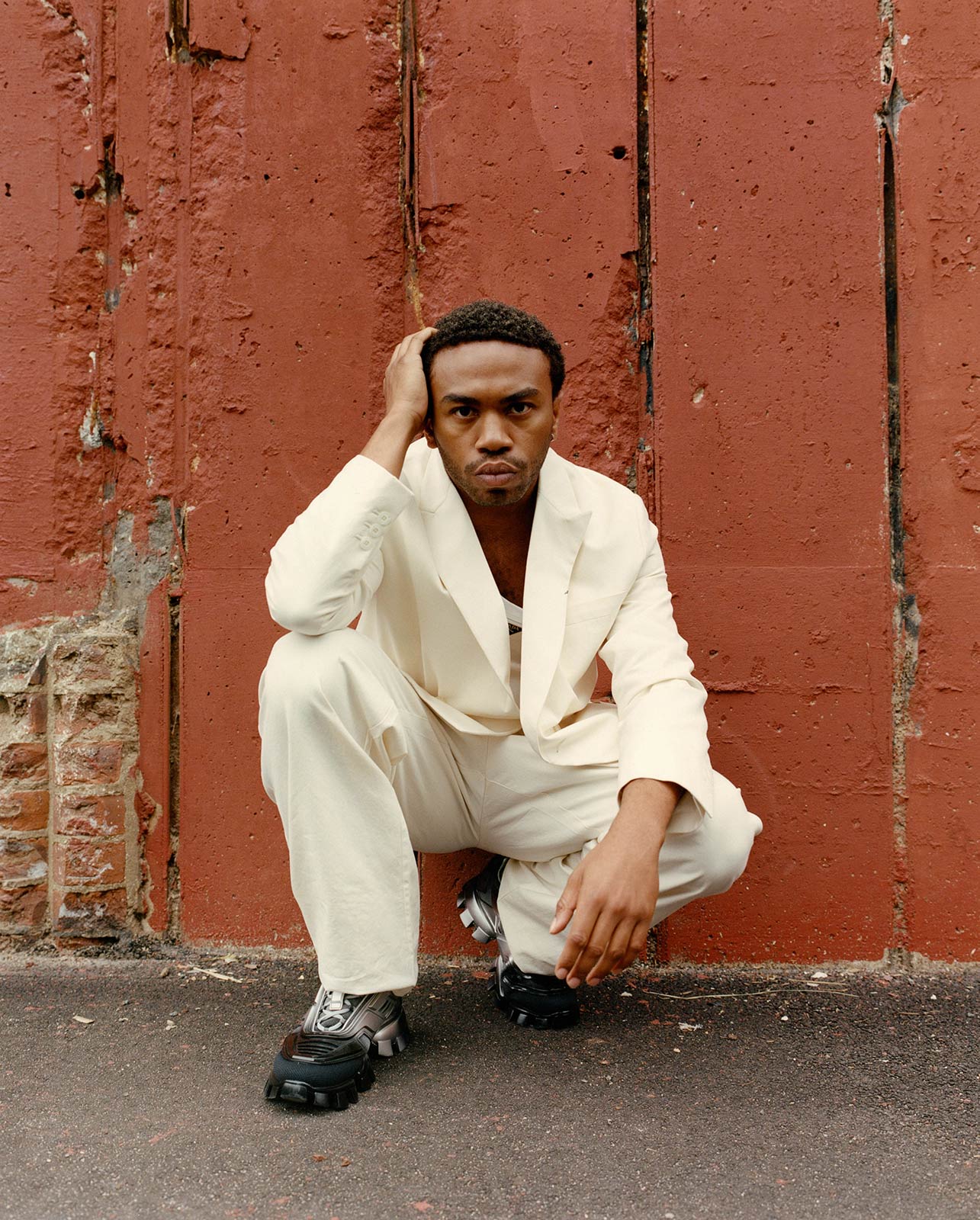

For Document’s Winter/Resort 2023 issue, the musician and the artist meet for the first time to explore the evolving principles and practices of video-making

Kevin Abstract flashes a toothy grin, schmoozing a security guard into submission so that he and his friends can orchestrate a bare-bones music video in the frozen-food aisle of a desolate supermarket. The cord of an unplugged mic drags behind him as he dives into an improvised performance of his 2014 single “Drugs,” while his friends browse premade pizzas in the background, drifting in and out of frame.

“Drugs” reflects the tropes of the era’s popular rap videos—easy confidence, an eager entourage, and unmediated contact with the camera—save for one glaring disparity: its homespun production. Abstract has often cited his MacBook as his preferred medium for art-making; he uses it to teach himself how to emulate his acclaimed predecessors—like OutKast and Odd Future—and for experiments in differentiating his work from theirs.

He is not hindered by a fixation on achieving mastery of emerging technologies—he’s more concerned with how he can use them than with how they are intended to be used. Abstract treats his art as though it’s no more deserving of immortality than a fast-passing thought. A few years ago, he removed his critically-acclaimed debut, MTV1987, from streaming services when he decided he didn’t like it much anymore, equating the act’s significance with that of deleting a tweet.

Clifford Ian Simpson grew up in Corpus Christi, Texas—but Abstract, his adopted persona, was raised on the internet. He was born on the exact day in 1996 that Microsoft and NBC dominated headlines, announcing they’d be infiltrating American households through round-the-clock televised news as MSNBC—arousing early fears of digital hegemony and, consequently, homogeneity. Abstract’s life has taken place, in near equal parts, between the digital and physical worlds, where he’s offset a complete corporate takeover of the web as a prosumer of its miscellany. While modern proverbs equate technology with distance—a means by which we separate ourselves from the real world—Abstract has continually used the internet to keep his work grounded in reality, and accessible to the realities of others.

His music collective, BROCKHAMPTON (which was born of a post by 14-year-old Abstract in a Kanye West fan forum, asking, “Anybody want to make a band?”), opened digital doors to its followers, streaming live shows via YouTube when venues were unable to accommodate the totality of the group’s fanbase. And while social media often invigorates the meticulously crafted personae of creatives—built on fragments that fortify their commercial allure—for Abstract, it’s a means of achieving greater vulnerability than the physical world seems to allow. He’s tweeted plainly about his struggles with mental health, in an offhand way that feels true to experience: “life can fuckin suck big time.” Music fills a similar role in his life. In fact, he came out in the studio while recording his 2016 album American Boyfriend: A Suburban Love Story: “My best friend’s racist / My mother’s homophobic / I’m stuck in the closet / I’m so claustrophobic.” Raised in a conservative Mormon household in the South, he cites the internet as a place that helped him overcome self-hatred as a queer Black kid.

Web tutorials on the more technical elements of videography and DVD directors’ commentaries on the methods of moviemaking served as the basis of Abstract’s artistic education. His web-based coming-of-age prompted his move to Los Angeles, where the imagined world of the artist, now 26, continues to manifest in reality. He’s confirmed that BROCKHAMPTON’s final record will be released later this year; he’s successfully established himself as a solo act; and he continues to augment his visual legacy, acting as a consultant on HBO’s Euphoria and sketching personal narratives in self-directed music videos—merging an unorthodox technical approach with tributes to cinematic archetypes to achieve intimate storytelling.

Video artist Charles Atlas—who cemented himself as a staple of New York’s avant-garde dance scene in the early-’70s—has been equally quick to incorporate new technologies into his practice. (Though, it should be noted, aside from a newfound addiction to TikTok, he does not partake in social media.) From his video collages and installations—which often feature digitized numbers, geometric figures, abstract imagery, and experimental dancers—to his TV specials—which depict propulsive corporeal movement and magnetic drag queens set to unsettling audio—each of his projects is based in multimedia. Atlas pioneered the art of “media dance,” where performances are made not for a live audience, but for the camera. He developed the form through intimate collaborations—most famously in his decades-long work with the father of modern dance, American choreographer Merce Cunningham.

Atlas intentionally builds his work to exist offline. His most recent installation, The Mathematics of Consciousness (2022), is an all-consuming experience for its audience, stretching across a hundred feet of brick, blending science, math, drag, and dance in an immersive 30-minute experience that, once taken down, will no longer be available; its temporary nature is part of its allure, emboldening the philosophical questions it poses. Consistent throughout Atlas’s decades of work is a playfulness, embodied by his dexterity in adopting new technologies in his experimental renderings of kinesthetics. Some of his earliest-known works, which emerged almost immediately after his move from St. Louis, Missouri to New York’s East Village, established the artist as a revolutionary. His docufantasy Hail the New Puritan (1986), in which Scottish iconoclast Michael Clark plays a fictional performance artist, is a precursor to the mockumentary—yet the film is far more inventive than those that followed it, sketching a vision of urban queer culture through surrealist dance performances and sex scenes. He eventually experimented with porn under the name Jack Shoot with Staten Island Sex Cult (1998), which took inspiration from Heaven’s Gate and The X-Files, and broke the rules of gay pornography with its female-inclusive cast. The film earned him a nomination for Best Porn Comedy at the AVN Awards, which is widely considered ‘the Oscars of adult films.’

Like the performers Atlas has captured, he maintains an elusiveness in his work. Where Abstract’s practice embodies the explicit, Atlas’s is embedded in ambiguity—but their ethos is the same, rooted in a desire to connect, and built from a sheer willingness to try. On opposite coasts, the two artists meet for the first time—virtually, of course—to discuss the function of movement in storytelling, the art of self-education, and how to find family in collaboration.

Megan Hullander: You both migrated to coastal cities, from the South and the Midwest, respectively, and within those places, grew up under conservative religions. Do you feel any lingering influence of that in your work?

Charles Atlas: I rebelled against religion before my teens. That transgressive feeling in my early work [stemmed from me] testing the boundaries of things. I think that comes from having rejected religion.

Kevin Abstract: When I was growing up, I would try to blend into whatever was happening around me, just because it felt safer. Once I got access to the internet and started making more friends online, I was able to find more people who didn’t grow up like me—especially [people who didn’t experience] a conservative upbringing. It showed me different sides of life and made me, maybe, hate myself less. I still identify with the rebellion you’re speaking about, because I felt like I had to lean into things that weren’t right in front of me to make the art I saw in my head.

Megan: That adoption of the internet manifested in not just the content of your art, but also the positioning of it. And Charles, you’ve been comparably quick to pick up new technologies and internet practices. Do you see this as closing gaps of intimacy, or creating enough distance to make it feel easier to share?

Charles: I don’t like people to see my work online. A lot of it is immersive, and you can’t really do that online—or I can’t, anyway.

Kevin, how do you feel about live performance versus [producing content for] online viewing?

Kevin: There are certain projects that make the most sense for me to have online, in a practical sense. I really do love just throwing things and seeing if they connect with people. I think it’s made my life easier as an artist, because I can control my own gallery. But if I’m focused on a concert—in a specific type of venue or something—I see a lot of value in that. It’s not like I lean toward one or the other.

Charles: Also, since I’m older, I’m generationally way different from you. I’m not on Facebook or Twitter.

Kevin: I’m trying to live like that.

Charles: But I am addicted to TikTok.

Megan: What does your feed look like?

Charles: I just let the algorithm decide what I should see. It’s changed lately; it used to be a lot of dance and drag queens, and now it’s science and fashion. I liked the dance part. But I don’t get that as much as I used to. I could pass three hours of time without even noticing. So, it’s good for doctors’ offices and things like that.

“Online, I was able to find more people who didn’t grow up like me—especially [people who didn’t experience] a conservative upbringing. It showed me different sides of life and made me, maybe, hate myself less.”

Kevin: I created my band through a fan forum. I feel like that gave me a lot of my success. I’ve leaned on the internet to teach me so much, in terms of how to put it all together. Not Twitter or Instagram, or anything like that. Just forums I was in early on, and YouTube.

Charles: With film and video, I’m self-taught from books.

I’m not afraid to learn new things—though some new things are a little hard to learn. I’ve tried 3D animation programs three or four times, and they never stick. Most of the work I do is very technical in nature. I try to learn something new [during the process of] every piece, so that I expand my range.

Kevin: When I was 18, I was obsessed with Boogie Nights. I’d watch it, like, every day. I learned how to make movies by watching them with directors’ commentaries. And I would watch the interviews of anyone I was into—fashion designers, filmmakers, rappers, whatever. I’d download as much information as possible and try to apply it to the stuff I was working on.

Charles: When I dropped out of college, I came to New York, because that was the place where you could see movies. I used to go three or four or five times a week, and I would sit through each film twice. The first time, it’s just the experience, and the second time, it’s for the mise-en-scène. Eventually, it got to the point where I could see everything in one viewing. That was my education.

Before I started working with dance, all I really wanted to do was make regular movies, like European narrative films. But working with dancers was my first chance at really making a movie.

Megan: How does movement inform the character you’re trying to build, or the narrative you’re trying to portray?

Charles: Dance is ready-made movement. So, that gets the ball rolling. I think of movies as move-ies. Things move in them—the subject or the camera. I don’t think about things moment-to-moment [when I’m filming]. When I started to work with Merce [Cunningham], the cameras were on tripods, and then we eventually took the tripod off and sort of moved around with the camera. It was an evolution, and I never went back.

Kevin: I’m just now starting to realize how important dance is to me. There’s the one video we have called ‘HEAT,’ and we do this silly dance—kind of like zombies—and sing together. I think I was trying to do this Spike Jonze-y thing, or even something like those old MJ videos. I just realized that this stuff has been in my brain since I was a kid, and it’s helped shape culture and the way we view the world. I realized, after hearing you speak about dance and the way you break down movie, that it has helped inform decisions I make when directing people.

Charles: My background is not in synchronized dancing, but I’ve been thrilled by watching [it]. I never really knew anything about dance until I started working with Merce. It led me to appreciate all sorts.

“I don’t want to blend in. I don’t want to just fit within whatever is happening currently in the zeitgeist; I try to twist it in my own way.”

Megan: Merce was such an epitomal figure of the avant-garde, in what might be considered its peak. Is there an equivalent of that today? How does subversion in art look different now than it did then?

Charles: I feel that avant-garde really refers to another period. In our current context, it’s subversive to tell the truth. I’m very progressive, politically. But in my work, I’m not addressing all those issues directly. I find things that I’m enthusiastic about, and I work with that in a positive way, rather than be critical or negative.

Kevin: I like that. I feel like a lot of interesting things are happening in the underground. There are a few—more so in music—artists that exist in the sky, and they sometimes take from the underground. Maybe then we’ll get something that feels like innovation, or magic, or at least has some sort of push to it.

Charles: Where do you look nowadays?

Kevin: I more so look to the past.

Megan: Does developing a sense of authenticity feel different when adopting the practices or ideas of a generation that’s not your own?

Charles: The advent of the internet really changed everything. It’s a whole different ball game [in terms of] how people find and use new music, and all kinds of stuff. It’s about addressing things that haven’t been addressed.

Megan: With that, do you feel the driving purpose of art is rooted in a desire to capture something about a moment in time? Or is it more about projecting toward the possibilities of the future?

Charles: I’m quite scared of where we are going as a country—in arts, politics, everything. I’m not feeling that optimistic. I don’t feel that, as an individual, I can make a big change in that.

Kevin: I’m more hopeful. I hear what you’re saying, though.

Charles: It’s also convenient, you know—my age. I’m on the other end of life from where you are. For me, [making art] is really about capturing what’s in front of me, and making it vivid for an audience. The future takes care of itself.

Kevin: I think I bounce between the two. I need to make things I would listen to, things I would like to watch. But I don’t want to blend in. I don’t want to just fit within whatever is happening currently in the zeitgeist; I try to twist it in my own way. That becomes challenging, because sometimes you can be so ahead [of the times] that it just doesn’t sound good—it doesn’t land at all.

Charles: How different is it, being a solo artist versus with a group?

Kevin: It’s a lonelier life. I’m used to collaborating with a lot of people. When I had an idea, I could bounce it off another artist. But it’s like growing pains—it’s going to make me grow up a little bit, and really think about my place in the culture and what I want to bring forward. It’s been difficult. I’m still collaborating with people, but never all at once—so it’s more intimate, the process of making music.

“For me, [making art] is really about capturing what’s in front of me, and making it vivid for an audience. The future takes care of itself.”

Charles: I like working with other people. I’ve had long collaborations over the years with people who I love. It’s really love. I’ve been part of a few different families over the years. There are people who I started working with in 1970 that I still work with. Not continually or often, but they’re still part of my family.

Kevin: That gives me hope for getting out of this lonely feeling—like, reframing these new people who I’m working with now. It just doesn’t really feel like it yet, because for the past eight years of my life, I was with one specific creative family.

Charles: In some collaborations, I’ve been in sort of arranged marriages with people I didn’t know before, and it doesn’t usually work out. But people I’ve worked with who I knew as friends first, and then they became a part of my work—when I made films [with them], it felt like I was making the right choice.

Megan: That sense of family, that you both mentioned, speaks to the intimacy and vulnerability that’s required in making art. Are there spaces you use to grapple with the self-analysis that requires, or do you feel pressure to lean into pain for the sake of art?

Charles: Oh, I just feel I’m stuck with who I am now. I’m not going to change much. I can still change, but not in that direction.

Kevin: That’s awesome. I started, like, seeing an actual therapist in the middle of the pandemic. I never saw her face, because it gave me some sort of anxiety. I’d walk around my neighborhood, talking to her five days a week. That just slowed down last summer. It’s very helpful, but it’s very draining.

Charles: Well, every time I’m making a new piece, I get very anxious until it’s finished. Anxiety is [sometimes] more and sometimes less, but it’s always there. I discovered [that] early on. When I was working with Merce—despite all his success, and all his huge accomplishments—every time he made a new piece, he was in a really bad mood until it premiered. I’ve kind of accepted it now as part of the process.

Kevin: I relate to everything he just said.

Charles: I don’t ever start out with a fully formed idea—I have a feeling, or something like that. It’s a little nebulous and you are wondering whether it’s ever going to turn into something decent. The only solution to art is to just keep doing it.

Groomer Elias Sacaza, Michele Wilderman. Photo Assistants Nikolai Hagen, Brandon Jones. Stylist Assistants James Kelley, Shaoul Avital. Production Starkman & Associates. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan. Talent Director Tom Macklin.