In the era of Spotify Wrapped, media consumption is a source of community. But does broadcasting the content we consume change our taste?

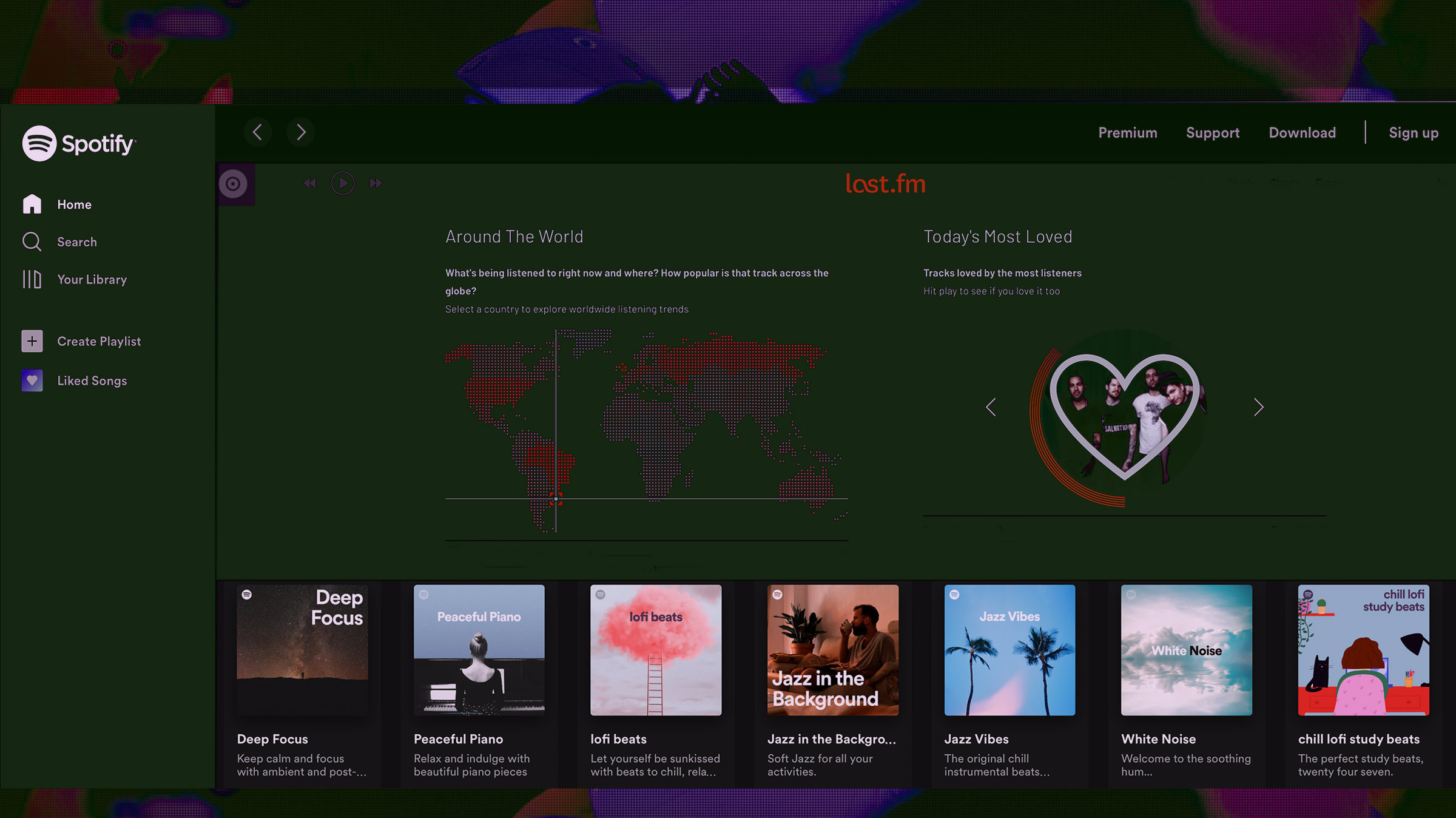

For one week every year, my social media feeds are inundated with Spotify Wrapped posts from friends, mutuals, and acquaintances, each sharing infographics of the artists and albums they had on loop. I’m not the only one who experiences this: In fact, the advent of Spotify Wrapped led to a 21% bump in app downloads in the first week of December 2020, when the feature first premiered. It’s an extension of one of Spotify’s older features: social sharing, or the ability for your friends to see your listening activity in real time, whether you’re proud of your content consumption or not. So how does today’s hypervisible, constantly documented media consumption change the kind of content we seek out?

When we start thinking about how we’re being perceived, it’s bound to impact the way we act—a fact I can attest to when I open Spotify and find myself wondering, What are my friends going to think about what I’m listening to? Of course, the idea of guilty pleasure music is not new; but before, it consisted of CDs shoved under car seats. Now, what we’re liking, viewing, and reading is hypervisible on apps like Twitter, Letterboxd, and Goodreads, which broadcast our media consumption to friends, acquaintances, and reply guys alike. It makes sense that we care about how we’ve perceived: Multiple behavioral studies show that humans act differently when we believe we are being watched. And with the digital conspicuousness that’s prevalent in mainstream social media—on Twitter, even posts we “like” are often broadcasted to our followers—it can feel like we’re always being watched online, even if we’re not. It’s no wonder those “do not perceive me” memes took off in early 2020.

When we navigate these sites, we are opting into the social economy of content consumption, though alternatives exist. On Spotify, for example, some might click the “private session” option, allowing them to listen anonymously. Others might decide not to use Spotify, or any of these other applications. But there is a sense of being left out of the conversation when you remove yourself; it feels almost necessary to overshare in some capacity to participate in a digital community. And these communities are crucial, especially for members of Gen Z. We’ve grown up in an increasingly digital world, where it’s not uncommon to make friends online; many of us ignored our parents’ “stranger danger” warnings, opting instead to make internet friends on Tumblr and Twitter. The pandemic has only exacerbated our tendency to delve headfirst into these digital spaces.

“Performing our personalities—or at least, our personas—online can complicate the distinction between what we consume for our own pleasure, and how we wish to be perceived by others.”

Enter: oversharing online. After all, what better way to be relatable than to tell the internet everything about yourself? A lot of people embrace putting their lives on social media. Take Victoria Paris, who took to YouTube and TikTok to “Big Brother” her life. Her near-constant uploads and appeals to relatability eventually resulted in virality, and brand deals with the likes of Anthropologie and Urban Outfitters. In Paris’s case, that online success quickly translated to real life success, in a process much more appealing (or at least, more rapid) than climbing the corporate ladder at a typical nine-to-five.

The tendency to overshare in these digital communities can be misleading, blurring the line between real friendship and parasocial relationships, with some followers even feeling entitled to information about influencers’ personal life and schedule. Exemplifying an extreme case, Paris recently uploaded a (now seemingly deleted) video, sobbing and begging her fans to stop touching her, following her, and chasing her down in public.

In an era where the content we consume is hypervisible, everyone is a celebrity, acting for a real or perceived audience. Performing our personalities—or at least, our personas—online can complicate the distinction between what we consume for our own pleasure, and how we wish to be perceived by others. And though participants in these communities often appear to be “sharing everything,” examining our own “media diaries,” and the motivations behind them, can be a worthwhile step in understanding who we are.